I’ve heard these same accusations made out of context, and I’m ashamed to say that I did not bother to track them down. I will in the future, because I’m familiar with how creationists distort quotations, and this is just classic dishonest manipulation.

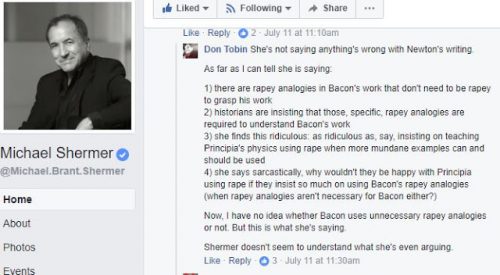

Recently, Michael Shermer (of whom I’m generally a fan) [pzm is not] claimed that Sandra Harding, a philosopher of science and influential feminist, had called Isaac Newton’s “Principia Mathematica” a “rape manual.”

Today, I read a similar statement from an anonymous source shared on Facebook which claimed that feminist and philosopher Luce Irigaray called the equation e=mc2 a “sexed equation” because she argues that “it privileges the speed of light over other speeds that are vitally necessary to us”. The original source of this claim is apparently a criticism of her work by Alan Sokal and Jean Bricmont published in 1997.

Both cases were repeated by Richard Dawkins (of whom I’m also generally a fan) in a 1998 essay entitled “Postmodernism disrobed.”

In both of these cases, the feminists were using what educated adults should know as a “rhetorical device.” In the former case, Harding was using sarcasm in her criticism of Sir Francis Bacon; in the second case, Irigaray was taking a critic’s argument to its (absurd) logical conclusion.

When we actually read what these feminist authors have said, it’s actually far more nuanced than anti-feminists claim. Here’s Harding:

One phenomenon feminist historians have focused on is the rape and torture metaphors in the writings of Sir Francis Bacon and others (e.g. Machiavelli) enthusiastic about the new scientific method.

…But when it comes to regarding nature as a machine, they have quite a different analysis: here, we are told, the metaphor provides the interpretations of Newton’s mathematical laws: it directs inquirers to fruitful ways to apply his theory and suggests the appropriate methods of inquiry and the kind of metaphysics the new theory supports. But if we are to believe that mechanistic metaphors were a fundamental component of the explanations the new science provided, why should we believe that the gender metaphors were not? A consistent analysis would lead to the conclusion that understanding nature as a woman indifferent to or even welcoming rape was equally fundamental to the interpretations of these new conceptions of nature and inquiry. In that case, why is it not as illuminating and honest to refer to Newton’s laws as “Newton’s rape manual” as it is to call them “Newton’s mechanics”?

Wait, what, you say? Bacon used rape metaphors? Yes, he certainly did. Here’s ol’ Francis arguing that we should study even fringe subjects or superstitions to try to unearth the actual causes (a sentiment with which I must agree):

Neither am I of opinion in this history of marvels, that superstitious narrative of sorceries, witchcrafts, charms, dreams divinations, and the like, where there is an assurance and clear evidence of the fact, should be altogether excluded. For it is not yet known in what cases, and how far, effects attributed to superstition participate of natural causes; and therefore howsoever the use and practice of such arts is to be condemned, yet from speculation and consideration of them (if they be diligently unravelled) a useful light may be gained, not only for true judgment of the offences of persons charged with such practices, but likewise for the further disclosing of the secrets of nature. Neither ought a man to make scruple of entering and penetrating into these holes and corners, when the inquisition of truth is his sole object.

Harding is not literally accusing him of writing a rape manual; she’s pointing that his science is viewed through the lens of a man living in a profoundly sexist culture. Bacon is not arguing that we ought to rape people to discover the truth, but Harding is showing that he is unperturbed by metaphors about “a man…penetrating holes” because his society sees nothing wrong with poking into things against others’ will, an attitude that doesn’t just affect relations between men and women, but is going to be reflected in an era of colonialism.

If you’re going to seriously study the history and philosophy of science, you don’t get to just say one set of words have profound meaning, while another set is to be clearly dismissed as irrelevant. This is the whole point of that dirty word, post-modernism: scrutinize what people said and put it in a context of meaning. Bacon’s word choices are seen as interesting and revealing, and we should recognize that even great scientists aren’t free of biases.

i’m terribly concerned about the opinions of career bad-faith agents.

…I would have thought Bacon was using a speleology metaphor: don’t be afraid of the dark, go through the entrance, walk into the cave or basement or dungeon and find out what’s in there.

Is the original Latin online somewhere? Does it even mention “a man” rather than “some-/anybody” ((ali)quis for instance)?

Harding and Irigaray… Hey, I remember skimming a chapter from each of them when I wrote about the Sokal paper!

I really wouldn’t come to the defense of Irigaray. The whole chapter was filled with obfuscation and bad puns (i.e. sciencey word salad), and it ended with a line about how she knew nobody understood it. Writers like that do not deserve the benefit of the doubt.

As for Harding, she was okay. Here’s what I said about her:

Ah, memories. That reminds me of a long debate we had in the comment section on Pharyngula, where I and “zoonpolitikon” extensively argued that Irigaray was not saying E=mc2 is sexed, she was pointing out the absurdity that the French language assigns it a gender. I brought up Harding back then, too.

Here’s a new one: one major criticism of Brownmiller’s >Against Our Will was that she proposed the false report rate on sexual assault was 2%. When I dug into the topic I found that A) she says no such thing, merely that one person with experience on the matter suggested it was a plausible number, and B) since then, the largest, highest-quality studies on the subject suggest the rate is a smidge above 2%.

This seems to be a consistent pattern among social conservatives: stumble across someone who seems to be advocating for a ridiculous position, but instead of double-checking they understand correctly they immediately leap to loud and repeated condemnation.

So it looks like this whole post is sarcasm. If you genuinely think that “entering and penetrating holes and corners” is a rape metaphor, then you’ve got bad understanding of English and anatomy, and an unfortunate tendency to leap to thinking about rape, rather than physical exploration of spaces. Thankfully, I’ve never met a human with a “corner”. I think PZ Myers is better than that.

I don’t see anything in that Bacon quote as implying a rape metaphor. Poking and penetrating is not necessarily a male activity, holes and corners are certainly not female, and nothing in there is suggesting that the said holes and corners have any will for the poking and penetrating to be against. It may be that some omitted context shows the inferred metaphor, or it may be that Bacon’s writings offer clearer examples. But so far, that wasn’t useful.

<deadpan>

What a shock.

</deadpan>

I’m not endorsing Harding or Irigaray — I’ve only read excerpts of their work.

I see some are already dismissing any interpretation of the metaphor that they disagree with. Why? That’s the heart of post-modernism: here’s one interpretation, here’s another, and here’s another. Analyze what influences lead you to accept one but not another.

Nature has a will? Agree with David @2 and John @6.

It’s interesting that three people so far find “plumbing and penetrating holes” to be a completely innocuous metaphor. Most recently Rob asks whether nature has the capacity to withhold consent — but why is that the question? Why isn’t the question whether nature has the capacity to consent? Yes, it’s inanimate, but what this suggests is that for Rob, the default is to be fuckable, and only in special cases does fucking come off the table.

(What conditions? Dunno. Perhaps when a woman says no in advance, and doesn’t dress provocatively, and doesn’t come back to your room; otherwise it’s a grey area, and the default is to go ahead and fuck it..)

Whether the “penetrating into holes” metaphor is innocuous or not, that’s unrelated to the main point that Shermer & Dawkins are misrepresenting what Harding said.

They misrepresented her partly because they couldn’t be arsed to figure out what she was actually saying — but partly because they wouldn’t understand her point if they tried. As #10 attempts, crudely, to illustrate.

A Masked Avenger @10:

If I associated looking for things with fucking, you might have a point. But why would anyone make that association?

Oh yes. Fearful thinking (the other side of the medal of wishful thinking) is really common there.

Well, first, I’m interested in finding out what Bacon meant and what else he had in mind. I wouldn’t be surprised at all to find a rape metaphor in this kind of work from that day and age. But what makes you think this quote is one in the first place? It’s only very recently, and only in English, that the meaning of penetrate has narrowed down like that. That’s why I asked for the original Latin. (Bacon’s Latin is very readable, it’s not the Aeneid!)

I’ve certainly come across violence metaphors in such contexts that struck me. Off the top of my head, there’s the 19th- and early 20th-century German expression for “without a microscope”, which was mit dem unbewaffneten Auge, literally “with the unarmed eye”… implying that science is a war against nature with the aim to force nature to give up its secrets, which apparently it doesn’t want to.

That’s part of some metaphors. Also, ignoring someone’s will and not caring whether they have one can easily one amount to the same thing here.

Correct. This is called topic drift.

#2

Here is part of De Augmentis Scientarum. I’m not sure if it has the relevant passage.

https://ia802606.us.archive.org/28/items/worksfrancisbaco03bacoiala/worksfrancisbaco03bacoiala_bw.pdf

Thanks! I can’t find it in there.

There are numerous instances of penetrare, which seems to be Bacon’s normal word for “get through”, “get to”, often said of sunrays and the weather; whether there’s a rape metaphor lurking behind that I don’t know. (There certainly isn’t one in the original sense of the word, but that tells us little about how Bacon used it 2000 years after Plautus.)

PZ left out this sentence that precedes the quoted strip of Bacon:

Casting nature as female and saying you have to “hound her in her wanderings” is pretty indicative of what Harding’s talking about here, and a quick search indicates that she included that line in her criticism. Following the bit PZ quoted, Bacon also talks about looking into the shadows but not being defiled, which fits with such an interpretation, but isn’t conclusive of it.

I’m a little taken aback by folks in the comments expressing skepticism that nature might be portrayed as a woman with agency when, you know, that’s literally the number one metaphor used to describe nature in English.

This use of “her” tells us more about the translator than about Bacon, who had no choice: “nature” is a “she” in Latin, as is “table”, “beard” and most of the words for “penis” while I’m at it. Most abstract nouns are feminine in Latin and indeed most of the Indo-European language family.

In fact, that’s where the metaphor in English comes from.

The passage is from the second book of De Augmentis Scientarum (colinday’s version is an abridgement, and only covers books 7-9). The phrase in question is as follows in the original Latin:

“Neque certe haesitandum de ingressu et penetratione intra huiusmodi antra et recessus, si quis sibi unicam veritatis inquisitionem proponat”

I would render the Latin grammar more accurately as “And nor, indeed, ought there to be hesitation concerning the going into and penetration within of cavities and recesses in this manner, if one proposes to themself the unique inquisition of truth”.

The OP’s translation masculinises the phrase to a considerable extent. “Quis” is the indefinite pronoun, “someone” and “sibi” is reflexive – it can be himself, herself, myself, yourself, but with quis it would be “themself” or “oneself”.

“ingressus” is not a particularly sexual word in Latin. It comes from in + gradior “to step into”, so the natural connotation would be with entering a property or area. “Penetratio” is used in a sexual context in Latin, though it has pretty much the same variety of usage as our “penetration”. It comes from “penes”, which is a grammatical particle meaning under one’s control or concerning one’s business (“penis” has a different indo-european root and derivation). Paired with “antra” and “recessus”, though, the metaphor is clearly one of spelunking or investigating old tombs. “Antrum” is most naturally taken as a cave or hollow in a rockface (which were often used for burial in antiquity), and “recessus” is pretty much cognate with our “recess”. The words have almost certainly been used as slang terms for sex organs, but that’s not their primary meaning.

#8 PZ

First, “already dismissing” is loaded language that seeks to marginalize objections to your claim. But to answer your question, it’s because no clear reading of the text supports your interpretation and because you have not made any argument that the text ought to be interpreted that way.

Now of course criticism of your claim is no reflection on Harding or defense of Shermer. But if your intent was to show that Harding was right about the rape metaphors, you haven’t done that so far.

A Masked Avenger:

If women are meant to be a metaphor for nature, then leaving aside the moral issues, it would be an ill-conceived metaphor for reasons Bacon presumably would’ve understood. They obviously do have that capacity and nature as a whole doesn’t.

It sounds to me like he’s simply saying people shouldn’t be above investigating supernatural claims — which are hidden so to speak, in metaphorical holes/corners, by virtue of the fact that they do not have adequate explanations (and can’t be given them because people are afraid to do so. Doing that will shed light on what’s actually happening, claims Bacon.

So: you shouldn’t you have such scruples. Why would a person like Bacon, or anyone in his time period, have them or say that they have them?

He explicitly says “howsoever the use and practice of such arts is to be condemned, yet from speculation and consideration […]” It’s true that people in that time did express all kinds of concerns about studying “such arts,” because they had tons of superstitious narratives, just as he said. They had “scruples” even about things which would sound completely innocent to us, like “speculation and consideration.” He thinks those are innocent too, and is not about to address whether or not those (dark) arts themselves ought to be condemned. Instead, Bacon is willing to entertain the idea that some actual things happened and the stories aren’t entirely made up, however incredible and superstitious they are, however bad you think some “witch” ought there might have been. So, he’s recommending those things be understood, even if you think witchcraft and so forth ought to be condemned.

(Or that’s what you should do, even if you’re going to merely say that you think they ought to be condemned, so as not to get into trouble with religious authorities, who expect everyone to waste lots of breath condemning things like that. I’d say that’s the less naive reading that we should take seriously here.)

Anyway, that’s why he said you shouldn’t have such scruples. It’s not because nature purportedly has a will, thus it can be raped in some metaphorical sense, given a baseless assumption (based on nothing in the text) that he’s implicitly claiming rape is okay. That would require a couple of pretty big logical leaps that don’t seem like they’re warranted by anything in this excerpt. Maybe somewhere else he said things like that — no clue — but I’m not seeing whatever it is right here.

Maybe you think it’s a poor choice of words, as a modern reader. But he certainly wasn’t addressing modern readers, and what he’s actually trying to say to them sounds quite reasonable to me.

David Marajanovic is correct about the preceding passage in #19. The text is as follows:

“naturae vestigia persequaris sagaciter, cum ipsa sponte aberret, ut hoc pacto postea, cum tibi libuerit, eam eodem loci deducere et compellere possis.”

“Hounding nature in her wanderings” is a rather poetic and misleading way of rendering this. It’s closer to “you might let yourself follow the signs of nature wisely, since nature itself spontaneously wanders off, so that having fixed it here you can, afterwards, whenever you like, lead back and compel (nature) to the same place.”

“Natura” is grammatically feminine in Latin, and thus takes “ipsa” rather than “ipsum” (“herself”). Admittedly there was a long tradition of portraying an anthropomorphised “Natura” figure in medieval Latin literature, which Bacon knew, but you can’t talk about nature in Latin without using feminine grammatical forms.

“Persequor” means to pursue or follow (per + sequor, “thoroughly follow”). It can be used in a hostile or aggressive sense, but here the modifier “sagaciter” (wisely, sagaciously) suggests strongly against that. The metaphor seems more to be invoking images of animals or livestock wandering off in the forest (“vestigia” can mean “footprints” as well as “traces” or “signs of”) – the truth about nature has got lost and it’s up to the inquirer to go and find it by looking for footprints and then tying it back up with a rope. That’s a somewhat loaded metaphor, true, and it speaks of a very domineering relationship between the scientist and the object of study, but it’s not really a sexual one.

I do not, however, think that there is nothing to be said about the scientific process having been conceptualised in gendered terms in the early modern period. Given the cultural climate of the time and the heavily gendered assumptions early modern people made about the world it would be very surprising indeed if they did not use their cultural vocabulary of gendered norms to describe their actions at least occasionally.

These particular Bacon quotes, however, seem poor examples to use in illustrating that when one looks past the translation at what is a lively but highly intellectual scholarly Latin. They are much better as evidence of gendered understandings of science in the Victorian age actually – the Longman edition which is cited was published between 1857 and 1870, so naturally its translators decided that the scientist must be a man, rather than just a someone, and that nature was a “her” be “hounded” rather than an “it” to be “followed sagaciously”.

I remember back in the ’90s when I first started to get into organized skepticism and believing all the stories about post-modernists and feminists claiming that observable reality is an opinion. There was a lot of “Ha ha, look at those idiot humanities majors”. Because if they were smart, they would be STEM majors like us. Of course, later I found out that those statements about “Newton’s Rape Manual” were basically the same as hearing a creationist say Darwin admitted the eye could not have evolved. Which is to say it means the person speaking has never actually read the work in question, so you don’t to give anything they say on the matter any credibility. I don’t think I’ve ever heard Dawkins, Shermer, or any of the other high muckity mucks in atheism that have used this quote out of context ever admit that not only were they wrong about what was actually said, but it would have been very easy to check. I’m not holding my breath.

As much as I enjoy a discussion of Latin, I agree that it seems beyond the main topic.

Whether or not Bacon intended these metaphors to be innocuous or loaded with ‘nudge nudge’ rape imagery, is not hugely important. Nor is demonstrated whether or not the “rapey” interpretation of Bacon’s work is correct. I’m not sure if that could be definitively settled without a time machine. There seems to be some validity to both of arguments and it is worth discussing and agreeing to disagree.

I’m more interested in the suggestion that this language in considered, by anyone, to be essential to understanding Bacon’s work. Even if these words were innocent at the time, they are clearly problematic now. Are college professor’s using these quotes, without comment, in their lectures?

Darwin used the term “races” in his writing, which should be noted and discussed in it’s historical context, but we would have a whole other problem if teacher’s were throwing that term around in Evolutionary Biology classes.

Because they can read English? “Entering an penetrating holes” suggests nothing to you? (Do you generally lack imagination? Perhaps evocative language really is lost on you.)

Again, the claim is not that Bacon was intentionally making a double entendre, nor even that he remotely intended to convey a sexual image at all. The claim is that certain metaphors seem innocuous to certain people for a reason. The fact that (a) it is casually employed, and (b) it is then dismissed as meaningless, is precisely the point.

A more blatant example is the way that a college student today might say he “made chemistry his b*tch.” That has become fairly generally accepted among kids these days, and they would think you ridiculous if you pointed out that they were using the metaphor of raping a fellow prisoner. Of course they’re not. They’re probably not even aware of the origin of the phrase. In this case they DO know that “b*tch” is considered derogatory toward women, so as I said it’s more obvious why some would take exception to it. But within a sizable subculture this is considered completely innocuous, and any attempt to point out the origin of the metaphor would be dismissed.

Examples abound. The source material mentioned in the OP gives several.

consciousness razor:

Aww! Thanks for mansplaining to me what Bacon meant! English not being my native tongue, I couldn’t tell WHAT that paragraph was saying. Oh, whoops! Silly me — I forgot that English IS my native tongue. For a second I thought I spoke American, and that American was a different language. Silly, silly me.

cartomancer:

Indeed! The Latin scholars in this thread (of which I’m not one) are really just raising the question how much the choice of words reflects Bacon and his milieu, and how much it reflects the translator and (most likely) HIS milieu. Starting with the fact that the translation is distinctly gendered, despite the Latin (per your earlier post) being essentially gender neutral, and despite the fact that English did afford gender-neutral options at that time.

Two hours of Googling and Cartomancer beats me to it.

Anyway, the Googling tells me it’s a little irrelevant anyway as Bacon translated into Latin himself from English and as far as I see, the original English (edited versions from the 19th Century) seems to agree on “Neither ought a man to make scruple of entering into these things for inquisition of truth”

Which in turn brings me to the conclusion that any reading of the text can be coloured by one’s philosophy; biases; personal experience; motivations; etc; etc. The interpretation says more about the interpreter than what the writer originally meant. So whether you are thinking caving, rape or curiosity, the underlying and actually potentially useful message, is that “witches* might have something”. This won’t change.**

It’s easier for Newton – however much of a rape apologist he may or may not have been, F=ma.

.

* Going along with the 17th century witch definition for the sake of brevity.

** Obviously, the corollary of this is that this statement tells you more about me than truth. Funny old world.

A Masked Avenger @28:

Perhaps you’re overusing your imagination. Perhaps you’re obsessed with sex. Perhaps you’re titillated (or outraged!) by books on gardening and agriculture. So many perhapses…

I must say I did not realise that De Augmentis Scientarum was originally written in English and then translated into Latin. Or, at least, the first two books of it were – the rest was added in Latin for an international audience, so I discover. That’s modern history for you I suppose – you can’t just assume that everyone writes in Latin as a matter of course like we Classicists and Medievalists do.

Which rather puts the onus onto those significantly more familiar with early 17th century English usage than I am to determine what connotations Bacon’s language might imply. Though if the Latin versions are his own (it seems opinion differs on quite what his publisher’s introductions mean – one version suggests he translated some of the first two books himself, another that he translated all of them) then it has some merit to note that they suggest far less scope for problematic connotations than the English versions.

Still, I have at least discovered an interesting discussion for my Latin students to have at the beginning of a lesson when I next end up teaching some.

cartomancer @24 :

One bit of support for using ‘hound’ in the translation is that the essay is addressed to King James I, who was known to be obsessed with hunting:

so it would be quite believable that talk of following signs, and driving ‘Nature’ back to the same place, could have been meant as a hunting metaphor, in which case ‘hound’ might be very appropriate.

ethicsgradient, #34

The fact it is dedicated to King James is a very interesting one, and clearly important in how we assess Bacon’s writings. Indeed, this very passage about the scientific validity of investigating supernatural claims of witchcraft and sorcery can be seen very much in terms of sucking up to James, who had a keen interest in these matters. James presided over witchcraft trials against political opponents in Berwick in 1591, and even wrote his own treatise on witch hunting – daemonologie – which was published eight years earlier. Elsewhere in De Augmentis Bacon praises James’s recent treatise on the nature of kingship – Basilikon Doron – so he knew what he was doing. Sucking up to a new king from a new royal dynasty was the order of the day among English intellectuals and civil servants in 1605. In Bacon’s case it seems to have worked too, given that he was made Lord Chancellor and Viscount of St. Albans. William Shakespeare tried a similar thing with Macbeth, which also played on themes of witchcraft and legitimate Scottish kingship.

However, if it was a hunting metaphor Bacon was trying to convey in the Latin version then he chose somewhat obtuse words for it. Latin has perfectly good words for evoking the business of hunting – venari is the obvious one – and “persequor sagaciter” is rather abstract. Though the phrase was apparently written in English first and then translated into Latin for a second, international, edition. Which suggests, perhaps, that it was a hunting metaphor in the highly rhetorical English version addressed to keen huntsman King James and then turned into a more abstract evocation of searching and inquiry for an international scholarly audience.

Thanks, cartomancer – your Latin is (unsurprisingly) better than mine!

That’s interesting that it’s a Victorian translation. That explains a lot!

What I had in mind the whole time was this cautionary tale about a philosophy student who didn’t know Latin and tried to study the use of “the god”, “a god” and “God” by Augustine of Hippo – who wrote in his native Latin, which doesn’t have any articles, so the theology the student was studying was the translator’s and not Augustine’s.

That would really surprise me. Science theory, to the extent that it’s taught at all, is not taught using literature that’s hundreds of years old. Using old quotes, or new quotes, in a lecture is not common at all in the natural sciences at least. The history of science is taught, if at all, only as optional specialty courses, and there you’d definitely get lots of commentary. In short, very few scientists have ever tried to understand Bacon’s work.

Very few biologists alive today have ever read more of Darwin’s work than a few quotes from the Origin. PZ has; I haven’t. The trick about science is that, if it’s done reasonably well, you can understand it without needing to understand its history. (I remember explaining this to a quietist religious fundamentalist here on Pharyngula maybe 10 years ago. He was very, very surprised.)

Er, three things.

First, people really do vary widely in how active their imagination is.

Second, not everyone’s imagination is canalized in the same ways; there’s both individual and cultural variation in there (and who knows what else).

Third, even in his age and culture, Freud’s patients were not representative of the population at large; they were leading about the most horrible lives that could be led by rich people at the time. I strongly doubt there are many people today who think of a penis every time they see something peg-shaped, let alone of a vagina every time they see a box. And if they do, maybe it’s because they’ve read Freud?

(Personally, it seems to me that I, for one, think in metaphors much less than a lot of other people. But I have nothing like a quantitative study on that to offer.)

…Oh, BTW, electric plugs and sockets are apparently called “male” and “female” in English…? I learned that from the Internet just a few years ago; that metaphor doesn’t seem to be used in other languages and may have been coined by someone who had heard of Freud.

It does happen that metaphors become innocuous because their origin is forgotten. Comparison to other languages within Western culture makes clear that fuck you was originally short for I fuck you – a rape threat. I think you’ll agree it’s not meant or understood as a rape threat today. But that’s beside my point.

For the record, if I worked with people who used the metaphor you present, I think I would at some point gather enough spoons to ask them if they’ve thought about what they’re implying; after all, as you point out, the origin of that phrase is still transparent enough that it is, in fact, widely understood as misogynistic. But that, too, is beside my point.

PZ offered one particular Bacon quote as an obvious example of a rape metaphor. My point is that that particular quote is not an obvious example at all.

That’s it. My point is not the point of the OP. I see that point and simply have nothing to add to it.

(I’m not even saying that Bacon didn’t use rape metaphors elsewhere. I haven’t exactly looked for them.)

Oh, that reminds me – “virgin land”, “virgin soil” (y’know, unplowed), and Guyana was once called “a land that still has its hymen”. :-S If that’s not a rape metaphor, it’s a Cpt.-Kirk-inevitably-sweeps-everyone-off-their-feet metaphor, which still makes me queasy.

David Marjanović:

Right. That’s widely done for other types of adapters, joints, fittings, etc., not just electrical stuff. (In the latter, I’m including not only power but also audio/data cables and so forth.) Go into a hardware store, for example, and if two things can go together in a vaguely sexual way, then one type is male and the other is female.

But if it’s a Lego sort of object with both types of parts, it is said to have a male end and a female end: the whole thing doesn’t have a gender but each side/end/connection/whatever is gendered separately.

I’ve never needed to know…. What is used in other languages to distinguish them? I could just guess concave and convex, protruding and intruding, maybe a few others.

The use of ‘male’ and ‘female’ in English for shaped parts even predates Bacon. From the Oxford English Dictionary:

1585 J. Banister Wecker’s Compend. Chyrurg. ii. 273 If it haue a sharpe point (which you shall finde by searching with your probe) then you must vse the female propulsorie instrument, but if it haue a hollowe or socket, the male propulsorie.

and many more uses from before Freud.

consciousness razor:

At least in Spanish, it’s exactly the same: macho and hembra.

If I may set aside for another moment the lazy and dishonest ‘quoting’ done by Shermer and Dawkins in order to dismiss postmodern feminist writers, which nobody here seems to be seriously contesting, there is a fundamental aspect of the whole postmodern modus operandi that I find deeply troubling. As PZ says (at 8):

Yeah, and as Blattarfrax says at 31:

And this is the problem. Postmodern deconstruction never seems to say anything of permanent value about the text under study, except that it could be interpreted so-and-so, if you only view it in a such-and-such a context and wearing a particularly colored pair of glasses, which really only tells you something about the people choosing that particular interpretation (or, if you’re lucky, about the power of imagination and literary skills of the postmodern writer doing the particular deconstruction).

I don’t get the value of this. I mean, perhaps there’s literary or artistic value in such exercises, but what is the intellectual gain?

If you are trying to understand a text from, say, a historical perspective, this is worse than useless: why make up contexts for interpretation? These is only one historical context of relevance (unless you reject the existence of an objective historical reality, that is…). And if you are trying to understand the original intended meaning, this is equally useless for similar reasons, indeed, this kind of games are precisely what you should not do to put yourself in the writer’s mind. Maybe PZ or somebody else here can explain to me what they get form such an approach to texts, because all I ever got so far is annoyance and exasperation.

Don’t get me wrong: I sympathise with Harding’s and others’ trying to expose the more hidden aspects of sexism pervading science, language and society, but again, postmodern thinking seems to me to pretty much the worst tool at our disposal for this.

Take the quoted passage by Harding. What is she trying to prove precisely? As far as I can tell, she claims that gendered metaphors used by Bacon and others are just as relevant as mechanistic ones for the interpretation of scientific writings and thinking. (But I may be wrong: the writing style may be a little too nuanced for me here, especially without knowing… ahem… the proper context of the passage). It that’s so, I believe that a ‘normal’ historical and linguistic analysis of such writings (something along the lines of what Cartomancer and others did in this very thread!) would seem to be the way to undersand such things. The more make up possible interpretations, the least you understand the actual minds and societies that produced these writings.