I already explained why I wanted to design a new course: because I was getting stuck in a rut of teaching the same thing, cell biology and genetics, every year, and because new courses are an opportunity for the professor to learn new things and acquire greater depth in a subject. But what specifically should I teach? I’ve actually got a secret list of courses I’d love to be able to dig more deeply into. Don’t tell anyone. I don’t want to get drafted into teaching even more new courses.

-

First on my list is Evolution, a standard course in basic evolutionary principles, all population genetics and math. That would be a wonderful refresher for me. But guess what? Like most universities, we already have such a course on the books, and it’s already taught here, by someone else. We’ve talked about having me take it over next year (especially now that I’m not getting my sabbatical, it’s likely) so it’s in the planning stages now. A two-year cycle, where I alternate between the course I’m planning now and the Evolution course would be kind of pleasant.

-

Another possibility is to dip into the realm of service courses and offer a class to non-majors. My biology discipline struggles to offer more courses for non-majors, but we’re stretched thin to serve just the biology majors as it is. All of the courses I teach have a prerequisite of being a major in biology, so I don’t get outside of my building much. One course I think would be useful for everyone, though, is a Human Embryology course; it might be popular with our pre-nursing/pre-med students, and I think it would have broad appeal. It would cover basic sex/reproduction issues, as well as the step-by-step details of development, but it would also be an opportunity to introduce new methodologies, from stem cells to CRISPR, to non-biologists. It would also have a strong bioethics component.

The drawback? It wouldn’t push my professional development in the field much, although it would be a wonderful exercise in pedagogy. This would have the potential to be a large lecture class (100 students? That’s big for Morris), and there’d be all kinds of challenges in dealing with a diverse audience. I’d be afraid that it would reduce to your typical ‘rocks for jocks’ kind of course, though, which would require some attentiveness to keep standards high.

I pushed this one to the back-burner. I’m itching for a deeper dive into the science.

-

Next, I rebound too far the other way. If I were at a school that offered a graduate program, I’d propose a Critical Analysis of the Extended Evolutionary Synthesis. People keep suggesting we need a radical renovation of evolutionary theory, and it often revolves around the topic of developmental biology. There’s good meaty stuff to talk about here, and lots of papers that make radical assertions about how evolution works, and they aren’t all by crackpots.

Alas, we don’t have a graduate school, and a prerequisite for discussing changing evolutionary theory has to be a solid understanding of evolutionary theory, so students would have to have a substantial background to even consider taking the course. This one is simply impossible to offer here. No students would be interested, so I’d be talking to myself.

Although, if I do teach Evolution next year, I could see sneaking a little bit of this into that course, in a unit near the end.

-

All right, I can’t offer a course that demanding here, but one thing I’ve often complained about is that biology curricula too often offer too little background in the philosophical underpinnings of the discipline. We do a little bit of that in our first year introductory biology course, but a little more depth would be great…so how about a History and Philosophy of Biology course, for biology majors? We offer a history of chemistry course here, so that would complement it nicely.

One catch: it’s difficult to categorize and the audience for it is a little vague. It would be really excellent to have some philosophy majors take the course, but then I’d have to loosen the science prerequisites a lot, and suddenly it’s an introductory course for non-majors, which isn’t how I’d want to pitch it. We have a sad deficit in philosophy/biology double majors, so it would be hard to get enough students at our small university interested enough to be viable, and it would be difficult to sell to my colleagues as a useful part of our curriculum.

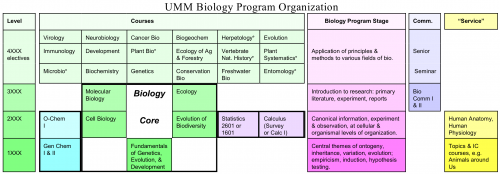

Before I go on to the course I am designing, I should probably mention that all-important constraint. No course stands entirely alone. They are all part of an integrated curriculum that leads to a degree in our field; you don’t get to just declare that you have a hobby horse, therefore students in biology should therefore also be interested in it. Every course proposal gets discussed by your colleagues, and they weigh in on whether it fits with the total program and is likely to contribute to student competence in biology. We actually have a strong coherent program, with evolution as a central theme.

So one of the things we have to consider is how a course fits in that diagram; how will it connect to all the other courses, and how will it draw on its prerequisites. I’m not designing a masterpiece that will be a monument on a wall, I’m painting a puzzle piece that has to link up with everything else we do.

So that was the major criterion that settled what course I would propose.

-

I’m going to teach a course in Ecological Developmental Biology. Why?

-

It addresses a long term interest of mine, the intersection of the environment, development, and evolution. There’s even a growing field with that name, eco-devo.

-

UMM has a reputation as a “green” university, and we have majors in environmental studies/sciences. Look, ma, I’m being interdisciplinary!

-

We have courses in ecology, development, and evolution, and this one course will tie them all together. See, I’m thinking about the puzzle pieces and how to link them.

-

Of those three facets, I consider myself strong in evolution and development, but rather weak in ecology. That means I have motivation to strengthen the third leg of the triad — professional development!

-

To my great relief, there is already an authoritative text in the field, Ecological Developmental Biology, by Scott Gilbert (every developmental biologist knows that name; he wrote what is probably the standard text in the field). This simplifies everything; I’m not building a course totally from scratch, but have a nice framework already in place.

That’s what I proposed to my colleagues, and after a few discussions and constructive criticisms, I filed a formal proposal, which was approved by the larger unit and the university.

-

All that was worked out last year. As it turns out, though, you can’t just say, “Here’s my textbook! Done!”, there’s a whole bunch of other stuff — like setting up specific course goals, working out the details of the content, figuring out pedagogical approaches, and assessment (and what, exactly, am I going to assess?).

I’ll talk about that later, though. Right now I’m plundering the textbook for general themes and also doing external reading to find additional papers beyond the bounds of just the textbook.

Having a good textbook is 80% of the course-design work, I think. I’ve rarely had a good textbook for any of the courses I’ve designed—hours of looking at everything available either resulted in me settling for a poor-fit textbook, or (finally) writing my own. Preparing a new course for me often involves learning a lot of new material—I often have to study for a year or more to get up to speed on something enough to teach it confidently.

Writing a textbook is more work than I realized—I went into the task thinking that it would take about a year of effort and teaching the class once or twice. I’m going to be teaching the class for the fifth time next quarter and I’m about 80% of the way through a massive revision of the text.

Even with a textbook carefully designed for the course, it still takes me many hours to schedule the homework and lab assignments and the lecture topics to support them, so the remaining 20% of the effort is still substantial.

I guess it boils down to the question: do you want to be a great teacher, or do you want to be an original researcher/discoverer in biology. My peronal idea is: there is nothing wrong with “just” being a great teacher. There are too few of them already. But you will have to decide for yourself. What is it that you want?

It may not be an easy choice.

great idea or choice of a course.

How we got to here is a question whose answer would cover many areas

it is important because it is where we live here now.

I would take it.

uncle frogy

Questions concerning the diagram:

At the 4xx level, several courses are marked with a superscript 0, which could mean one or more of:

* taught every year

* each student must take n of these, with n probably equal to about three

* each of these courses has no other biology-department prerequisite

And I also note that there’s only an “Organic Chemistry I” (no II) requirement, no apparent physics requirement, and little detail on how the senior seminar fits with the rest of the coursework. (Color me a little bit confused by those first two.)

Care to elaborate, or is this getting too detailed for this context?

They are NOT offered every year, is what that means.

A lot of courses outside the discipline are not listed. There is a physics, math, and stats requirement.

They are not required to take ochem2 for biology; they are for biochemistry, and if they’re pre-professional.

As a young instructor on an English taught program in a Japanese university (I often feel very alone!), I find this very interesting. I really need to get more contact with instructors at US / UK / Aus, etc universities, to help me develop more as an instructor.

Kevin Karplus (#1) talked about a good textbook. When I first started teaching, I basically followed Generic First Year US Textbook. Boring as hell. Almost no pedagogical value. But recently I have been shifting my Intro to Bio 3 course away from generic animal physiology, more toward biomechanics, and teaching students to appreciate the central importance of size, Fick’s law of diffusion, Poiseuille’s laws of fluid flow (i.e. blood in veins), and similar concepts. It really feels much more solid as a course, and helps students understand that organismal physiology is really trying to solve a fairly small number of problems.

Sadly, there is no one textbook for this, but I have really enjoyed the work of Steven Vogel (Comparative Biomechanics among others)

I think you would do an awesome job at rotating into the Evolution course. But ‘all population genetics’? That does not seem like fun to me. I teach our departments’ evolution course, and of course I do population genetics & math for a few weeks, but I also do a wide range of other topics including the essential standards (phylogenetic trees, evolution of sex & sexual selection, origin of life), plus a # of other topics of choice. It’s up to you, but I really would not be into a whole semester of population genetics.

The Eco Devo course would also be great, and I expect you would have a ball with that. But would this be a 4000 level course? Looking at the chart it appears that your department has a large # of 4000 level courses already, and maybe another such course will be significantly competing with other courses at that level. I only say this (& I certainly don’t know what it is like in your department) since the situation we have in our department is where we are saturated with upper tier courses & some of them suffer from low enrollment since there are so damn many of them. But I do not know of your department, and it could be different there.

Yes, the evolution course is more than just popgen. I was being lazy, because I’m not writing about that course just yet. Ask me again next Winter break.

Not all the upper level courses are offered every term — we typically have 3 or 5 per semester, so with 50-100 students we’re just about right. This is a small liberal arts U, we like small classes, so my eco-dev course has something like 15 students enrolled, which is just perfect. Genetics will typically have 30-40 students.

I’ve taught a large swath of courses in “media arts”. The joke used to be “Give it to him, he can teach anything”. The things that drove me crazy; bad or non-existent textbooks, awkward syllabus formats that had more to do with administrative pigeon holes than teaching, those damn rubrics, and computer techs who locked down functionality of the room’s computers to make their jobs easier.

This is clearly a situation where I have a certain hammer (and your course looks like a nail) but as a physiological ecologist I see a central role for physiology in an Eco Devo course. Would be happy to chat anytime about ecophys and physioeco (which never works quite so well as a word).

I agree! The catch is that I don’t have time to include more of that — I’m already planning to spend a big chunk of time on a crash course in basic molecular developmental biology (my hammer!) before getting into the meat of the course. I am having the students do an independent study project and report on it at the end of the semester, though, and eco-physiology is one thing I’ll recommend as an option.

If you think you are ready, then you must do the History and Philosophy course.

Obviously, you have the history, facts, and ideas down pat, but is there an overarching narrative, illustrated by historical events, that will leave biology majors, and even non-biologists, pointed in the right intellectual direction yet still having a solid sense of how they got to where they are?

I would totally love to see a course like this. It would be like Feynman at his best: talking about current ideas, but grounding them in what Newton or the ancient Greeks were thinking. Asking what one sentence would be best to communicate to your intellectual ancestors.

It would be a lot of work to do right. I’m about your age, and giving a talk next month on some obscure econ stuff. It’s taken me a 100 hours just to organize 500 years of banking stuff in order to explain the last decade. Ugh, I’m 54 years old and still don’t have a good, complete intellectual framework of my field.

Best of luck on whatever course you choose, though. Will you put it online? Please?

In my department, we have “Special Topics” courses that allow faculty to give specialty courses every blue moon. We’ve done a “Science of Brewing” a few times (very popular) and in the summer one of my colleagues is doing “Chemistry of Cancer” as a mixed grad/undergrad course. If your department has a course like that, you can do whatever you want. Finding a textbook or other suitable reference for specialty courses may be a challenge, of course…

Gorobei:

If I can respectfully disagree with a premise:* I don’t believe that there exists any “overarching narrative, illustrated by historical events” in history/philosophy of science that is not imposed through a combination of contemporary-to-the-instructor political biases and 20/20 hindsight bias. Just like evolution itself, there is no design (let alone designer!) at work; just delving into, say, the misuse of the “scientific method” (and the scare quotes are there because what was used isn’t the same thing as we use that term for today) concerning race — particularly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries — demonstrates that pretty well. And the less said about class bias being doctrine-directive (e.g., Kekule and the One Ring to Rule Them All, the benzene ring), the better. Note, too, that there’s no place for Michelson-Morley and its foreshadowing of 20th-century struggles with the chemical basis of genetics, because it doesn’t fit the narrative, either…

But that’s just my opinion. It’s not that teaching the history and philosophy of science is silly, it’s expecting an overarching narrative that’s silly. And “chaos is the norm, there is no single ‘story’ here” is a really difficult concept to get across in a three-credit undergraduate course, especially in a department lacking full-blown graduate program… when the vast majority of courses offered elsewhere at the school do pretend that there’s an overarching narrative. Exhibit A: Any survey course on “American Literature”…

* Odd background: Undergrad biochemistry and literature, grad literature (heavy politics/history context) and law… punctuated by certain Day Jobbe stuff…

Jaws:

Weird, I was just re-reading about Michelson-Morley and luminiferous ether versus dark matter.

I’m not sure we actually disagree: my personal view, at least as far as my own field is concerned, is that the overarching narrative is that of thousands of peoples making small steps in a locally correct direction while the big ideas, so obvious in retrospect, were missed or dismissed.

I’m probably biased towards synthesis over local optimization, but also to expertise over woo. So, I’m probably biased towards a course that would teach how we got here while not denying the intelligent people blundering into dead ends, the odd deserved flashes of insight, and the system that slowly filters out the correct.

I teach a course to high school seniors (mostly) in biotechnololgy in a semester for what should be a year long (or longer) course. Crunching this down to a semester was a boondoggle in and of itself. I can feel your pain.

@No One #9:

As someone who has occasionally locked down a computer or two, I can say that we most commonly do it to stop academics who think they know it all from screwing up the computers and making them unusable by the next class. ;-)

Rich Woods #17

As someone who has worked as over-night cleaning staff in office buildings,

I have often considered locking down the public toilets for similar reasons.

I saw that “rocks for jocks” comment! Bad, bad, bad PZ! At the university where I got my geology MS, primarily a teaching university, there were no “rocks for jocks” classes, though many jocks enrolled in those classes thinking they’d be easy. Oh, no, our geology department had high standards… as should all geology departments.

All the professors in the department taught at least one non-majors class each year. My adviser’s specialty among the non-majors classes was Prehistoric Life, a mix of paleontology and evolutionary theory, an upper-division class that satisfied a general science requirement. He loved teaching it, though it was a lot of work because he made those students write their asses off, and he’s a careful grader.

So, kindly refrain from using that disgusting phrase “rocks for jocks”.

(picks up soapbox and slinks off)