Once upon a time, I took a couple of upper-level courses in Roman history. I had a professor who spent a whole quarter on just Augustus, and it was revealing: there was no one moment where you could say that the Roman Republic became the Roman Empire, and even as it was happening the Emperor (who was just the Princeps, just another guy among all the other guys, he was just first in all things) was able to point to all these wonderful examples of the continuity of tradition. For example, the tribune of the plebs was important: he was elected by the plebeians to represent their class, and he had all these abilities, like being able to propose legislation directly to the people for a vote, and he had the power to veto legislation. The position was a key check on the power of the aristocracy.

Augustus didn’t get rid of it. He just adopted the tribunician power for himself. So you could go looking for a tribune of the plebs to represent you if you were plebeian, and still find him…he was just the Princeps himself, which kind of defeated the whole purpose, but literally, one could argue you hadn’t lost anything. The fall of the Republic took decades, as all the diverse checks and balances got consolidated into granting absolute power to one individual.

Paul Krugman has been reading some ancient history lately, too.

But the ’30s isn’t the only era with lessons to teach us. Lately I’ve been reading a lot about the ancient world. Initially, I have to admit, I was doing it for entertainment and as a refuge from news that gets worse with each passing day. But I couldn’t help noticing the contemporary resonances of some Roman history — specifically, the tale of how the Roman Republic fell.

Here’s what I learned: Republican institutions don’t protect against tyranny when powerful people start defying political norms. And tyranny, when it comes, can flourish even while maintaining a republican facade.

On the first point: Roman politics involved fierce competition among ambitious men. But for centuries that competition was constrained by some seemingly unbreakable rules. Here’s what Adrian Goldsworthy’s “In the Name of Rome” says: “However important it was for an individual to win fame and add to his and his family’s reputation, this should always be subordinated to the good of the Republic … no disappointed Roman politician sought the aid of a foreign power.”

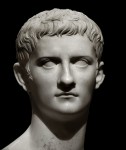

I’m sure historians will look back on the recent history of the American republic and find lots of similar concerns — the gradual aggrandizement of power in the hands of the executive, with the willing help of a senatorial aristocracy (and in our case, a subservient press). It seems like a good idea when you’ve got a competent leader, a Caesar or an Augustus or even dour old Tiberius, but then a Caligula takes the reins and you realize your mistake.

But don’t worry. You can eventually get rid of a Caligula with assassinations, calling in the Praetorians, and treason trials, which of course fixes everything.

I recently read I, Claudius. It starts with Claudius at a young age and follows his life in Rome in the court of the early Caesars and ends with his rise to emperor upon the assassination of Caligula. Well worth the read. I keep intending to watch the PBS miniseries but haven’t got around to it yet.

I guess we’ve failed to learn from history as we are repeating it.

Hear this Electors, do your job, don’t be just a mindless rubber stamp. I know it’s pointless to shout this here, as no electors read this site. just gonna repeatedly shout it everywhere as I can’t talk to an elector directly.

we are farked.

cheer assembly of protestors in each of the 50 state capitals, make our voices heard.

woohoo cheers applause cheers *whistle* chant clap clap clap

fnord

any body see that? get the reference?

This kind of illogic, (repeating obvious bad political ideas,) confirms to me we’re not sentient. We’re just apes that do a fair job of exploiting the scientific and cultural improvements of the few of us who had temporary, lucid moments. We look just like real people! Aw!

So in this analogy, FDR is Augustus? Or maybe FDR is Marius and Reagan is Augustus. Trump’s obviously Caligula, he’s not competent enough to be Nero.

There are some similarities, yes, but as with all attempts to compare Roman history with our own we must also bear in mind the rather important differences.

21st century America is not as democratic as it likes to pretend, but it’s far, far more democratic than the Roman Republic ever was. Those Tribunes of the Plebs, for example, could indeed propose legislation to the citizen assembly, but that assembly – the comitia centuriata – was arranged such that the wealthy had far more influence on the votes than the poor. The censors assigned everyone to property classes (centuries, originally 193 of them, after the Servian reforms of the 3rd century BC there were 373) every ten years or so, and the centuries had equal voting power however many people were in them. The lowest century (the “capiti censi” – literally “counted heads”, with little to no wealth to speak of) was vast and sprawling, and had the same voting power as the tiny handful of senatorial voters in the highest century. In fact the senators and equites, if they got together, could muster a majority all by themselves. As the centuries voted in descending order of priority, if this happened then nobody else would have to bother. So the transition from Republic to Principate was less a slide from democracy into tyranny than a slide from repressive oligarchy into much, much narrower and more repressive oligarchy.

The other thing to bear in mind was that Augustus’s reforms were carried out in the aftermath of thirty years of bitter civil war. If the people of Rome hadn’t been so strung out and brutalised by the instability of the mid 1st century BC (the Sertorian War, Sulla’s proscriptions, Pompey, Caesar, Antony, Octavian) it is unlikely they would have acquiesced to his transformations. By the time Octavian was sole ruler it had become quite apparent that the Republic had failed to ensure stability, and was a system no longer fit for purpose. Those like Cato and Cicero who tried desperately to save the Republican system were living in the past, blinkered somewhat by their own faith in the oligarchic traditions that had made them so powerful and respected. America is not even close to that situation today.

The long-term explanation for the collapse of the Republic must also take into account the fact that the Republican system developed in the 6th-4th centuries to run a medium-sized city state and regulate the ambitions of its aristocracy. It was in no way suited to running a vast mediterranean empire. Indeed, the Empire came first – the Emperors arrived centuries later as a solution to the problems Empire created. The biggest such problem was the vast power that accrued to proconsular generals away on decades-long campaigns of pacification and conquest. Such generals ended up with loyal personal armies that depended on them for land and pensions upon discharge. The army was not loyal to the state, and the Senate tended to ignore their plight. The wealth of Empire – accumulating as it did in the hands of the already wealthy – also led to economic instability as the aristocrats seized vast tracts of land for their industrial farming estates from the poor and powerless. Land reform was a constant issue from the Gracchan era of the 240s/30s right through to the Principate.

A final thought. It is often supposed that the collapse of the Republic was a terrible thing for Rome, and the Principate was a much worse system all round. That’s the view we get from the wealthy aristocratic historians who would have been among the powerful oligarchs under the Republic, but for the majority of Romans it was either much the same or better. Augustus, with his sole power, actually put an effective system of public food regulation in place – appointing a praefectus annonae to coordinate buying up and shipping grain to the vast capital from the rest of the Empire. Previously the senate – rarely aware of the plight of the poor – had hindered the arrangement of such systems, preferring to stick with the ancient tradition of having the city Aediles distribute the grain when it came in, but making no effort to regulate the purchasing process back to source.

Indeed, it is often overlooked just how little the character of the man at the top actually mattered in Roman life. The historical record from antiquity emphasises the importance of great men, and the Emperor could make the lives of the aristocrats a nightmare if he chose to, but Emperors were not in control of the economy and did not have sweeping political programmes like Presidents and Prime Ministers do today (an Emperor had no political party behind him for a start, so there was no core of people to ensure ideological continuity or a continuous power base). They could arrange social legislation to regulate the lives of the citizens, order military action and appoint civil servants, but Roman government was far less intrusive than we are used to. Mary Beard likes to draw attention to the thousands of statues of the Emperors that dotted Imperial Rome as a nice metaphor for how most Romans tended to view the Emperor – the heads were removable and could easily be swapped when the new one came to power (or even re-carved so the marble didn’t go to waste). The new Emperor, to them, was basically just a new face on the coins and the statues.

As soon as I saw the heading I was looking forward to the added information that would come with a cartomancer comment :-)

(If it helps spur anybody anywhere to look more critically at the current situation, though, I’ll take a pinch of glossing-over in my historical parallels no bother)

Mobius@#1:

I keep intending to watch the PBS miniseries but haven’t got around to it yet.

Do eeeeeeet!!! It’s great. Besides, Patrick Stewart puts in an appearance as a particularly blockheaded Sejanus. And there is some really great acting all over the place. Derek Jacoby is fantastic.

I avoid watching any of them because it usually triggers a binge-watch and then I wake up the next morning in a heap of nacho crumbs and empty bottles of wine.

opposablethumbs, #7

It is rather like my bat-signal, I have to confess…

I do think it is a very worthwhile exercise, comparing ancient with modern. Indeed, Classicists have had to become champions of precisely this kind of discourse over the last forty years or so – to save our discipline from being seen as the quaint and pointless entertainment of public-school toffs if nothing else. But the exercise is a worthwhile one only if we recognise that we are dealing with complex issues that don’t map neatly from one period on to another. The ancient world can give us perspective on our debates, but it can’t give us concrete answers or ready-made solutions. As Mark Twain observed, history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme. Sort of. If you squint quite hard.

Which is why I try to balance the discussion. When there is a danger of dismissing the relevance of the past I champion it, when there is a danger of seeing too much of ourselves in the past I sound a note of caution.

In this particular case I am reminded of a lesson I taught earlier this year on opposition to Augustus during his reign, which I began by discussing Donald Trump and the opposition to his presidential campaign (it was April, I had no idea he was actually going to win). When the class had enumerated the various groups arrayed against the wig monster – rival aspirants for the Republican nomination, the Democratic party, business rivals, people suing him in court, ideological opponents – I switched the picture on my projector to a statue of Augustus and got the class thinking about whether his opponents could be grouped in similar ways and what the important differences were. One thing I hoped they would take from the exercise was that, although Augustus has gone down in history as a great statesman and wise ruler, many at the time would have seen him in exactly the terms we see Trump.

Stop hitting yourself.

Stop hitting yourself.

Stop hitting yourself.

Stop hitting yourself.

….

cartomancer@#6:

The historical record from antiquity emphasises the importance of great men

This is a problem with history, in general. Historians haven’t got a metatheory of history that explains broad trends, so they still reach for the idea that there’s a “great man” that is catalyst for events that probably represent broad trends that were going to happen anyway. Of course there are important people who shape and change events, but again, unfortunately for the historians, they can only point at them and say “look!” The people who are involved in historical events at the time when they are happening are often the ones who were standing by on the sidelines – which gave them a good view but means they were uninvolved and often biassed. That’s without factoring in the deliberate propaganda, which also brings a lot of distortion.

I’m always particularly annoyed when people throw out the Santayana quote. History never repeats itself but we can perhaps learn a lot about how untrustworthy humans and human memories are, by studying it.

Yep thanks that cartomancer. Nuances help.

My father, a retired history prof, said that history seems to progress faster now than it did in the past. If true it would make sense; news travels faster, people travel faster, and our population (the substrate for ideas) is a lot denser.

Sometimes it’s hard to believe you can put the progressive experiment back in the bottle. You can hit it with a stick, you can bruise it, but the fact is that kings have slowly been going extinct for the last thousand years.

This doesn’t sound too dissimilar to the US situation (if you squint enough). Rich people get far more influence than the poor do: the financial cost of drowning out everyone else’s free speech means that almost only rich people can accede to higher office. So we have rich people in power, whose friends are rich, and who owe their position to help from other rich people.

“History doesn’t always repeat itself. Sometimes it just screams WHY DON’T YOU FUCKING ***LISTEN*** and whacks you upside the head with a stick.”

Just who was Marcus Antonius and what did Cleopatra rule again?

Yeah, he *really* violated that rule, all while Octavian was consolidating his powers, culminating with his gaining the title Augustus.

I really should read up on the subject, it’s been decades since I have and some details are a bit ill recalled.

Still, history doesn’t repeat itself. Very similar events just happen to occur in very similar ways, over and over again.

Yeah, I know. I’m just being a lot facetious, out of pure frigging disgust.

People just refuse to learn.

I have a question for you, cartomancer.

Lately, I’ve made this observation, and I want to know if you might agree with me.

In setting up the US government, the writers of the Constitution and other founding fathers borrowed much from Greek and Roman ideas of democracy. I’ve come to believe that they left out one very important idea – the Cursus Honorum.

For those who are not familiar with it, it translates as “way of honor”. A Roman who aspired to a higher office had to first rise up the ladder of lower offices, thus establishing a career in public service.

I wonder if having such a rule would have helped to protect us from Trump. I know that people were distrustful of “career politicians”, but it seems to me that in order to run for the highest political job in the land, a candidate should have at least been required to have served in some sort of public office on the local, state and/or federal level.

As a Classicist looking in from across the pond, do you think that this was a serious omission by the founders of the US government, cartomancer?

magistramarla @ 16, there were two schools of thought at the crafting of the US Constitution.

On one hand, there was the desire to have the ability to replace the entire government within 7 years, the revolutionary school. On the other, there was indeed an acceptance of the *custom* of the Cursus Honorum. People didn’t just jump to governor, mayor or county executive, they did begin at the lower offices and through their efforts, advanced to higher and higher offices (or flubbed it and never advanced).

I believe that omitting that and simply expecting the custom to continue is what actually happened.

Just as the custom of the electors in the Electoral College was to protect the nation from what is happening as we speak, in defiance of the expectation that duty to nation over loyalty to political party was what was expected.

multitool@12: “kings have slowly been going extinct for the last thousand years”

Under the greeks and phoenicians, a good bit of the mediterranean were republican city-states where the head of state frequently changed peacefully. Rome itself was run on the same model. After the end of the roman republic, there were a bunch of monarchies for over 1,500 years.

This is not a monotonic process at all.

The peak of power of European kings I usually think of being the 17th century. The enlightenment was 18th century, and that’s when the push-back against absolute monarchy really got going, culminating in the US Declaration of Independence. It’s only since then that kings have been falling.

I see no reason to believe we couldn’t get back to a period of strongmen being in power. The only thing that gives me hope is that it took Rome a century or two to wipe out its republic, whereas other cases of reversion have been from much shorter time spans.

@#11, Marcus Ranum

Ooo, ooo, can I trot out a pet idea of mine, which is semi-relevant? Of course I can. ?

Classical physics circa 1900 had the notion of time-reversal symmetry: if you could reach out and reverse the direction of every single particle in the universe simultaneously (a tall order but in classical physics a reasonable thought experiment), then the universe would “run backwards”, directly mirroring the past.

Quantum physics rejected the idea for good reasons (uncertainty makes such a reversal impossible anyway) but came up with a sort-of-similar notion: there is uncertainty, so individual particles would not necessarily trace the same path in reverse, and (as eventually amended) you would also have to reverse electrical polarity and particle spin parity, but if you could somehow make the necessary reversals, the rules would indeed still be the same for “running backwards”. (Look up “CPT symmetry” in Wikipedia for the boring details, or read the aging-but-still-readable-and-very-much-mistitled book The God Particle by Leon Lederman.)

The particles/events which violate basic time-reversal symmetry are mostly fairly rare, at least here on Earth (the sorts of things which can only be caused in an accelerator or a nuclear reaction), and in any event the “macro” world tends to smooth out quantum weirdness, which means that on a broad, basic level, even quantum physics suggests that the history of human-level things ought to be exactly as predictable, no more and no less, as the future.

So, in other words: if quantum uncertainty makes the future completely unpredictable to the degree we often like to imagine it is, then it also makes the past so uncertain that even human memory of events must be completely unreliable beyond a few years — our own memories from a decade ago, no matter how well-supported by artifacts, might as well be fiction. Or, to simplify even further: either history books are lies from beginning to end, or else psychohistory from Asimov’s Foundation series is actually a plausible thing (although in practice it might be impossible to formulate, or might be too slow to use). Neither possibility is really comfortable, is it?

(I pointed this out to a friend who was a physics major and worked in a laboratory, and she said “yes, and?” But it’s not at all common knowledge, so may be worth mentioning.)

Magistramarla, #16

My guess would be that, as statesmen with an 18th century view of Roman history, they regarded the Cursus honorum as one of the inflexible elements of the Republic that eventually fell apart as demands were placed on it that it couldn’t cope with. Marius’s many successive consulships, Pompey’s precocious skipping of the cursus altogether, the increasing numbers of proconsuls and propraetors that were needed to govern the provinces – I think that the Founding Fathers probably agreed with later Roman historians that it was a restrictive system hostile to precocious talent. I suspect there was also an element of having to work with the material at hand – pretty much everybody who had held office in their world had held it under British colonial governments, and if they tried to exempt their own generation from the requirement they couldn’t really expect future generations to take it very seriously.

@15: her is another one.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gaius_Marcius_Coriolanus

History doesn’t repeat itself, no.

But what it does is rhyme.

Non sum Rex, sum Donaldus Capillamenti!

@The Vicar, how does it follow from our memories after a decade are useless, to written words and artifacts are lies?

Though the US did retain some, albeit watered-down aspects of the Roman cursus – specifically the imposition of minimum age limits on office holding. And, de facto, it seems like most politicians do tend to follow an ascent from lower to higher offices, so perhaps it was considered unnecessary to regulate it so precisely as the Romans did.

Though it must be remembered that Roman Republican “politicians”, at least under the system as it was supposed to operate, were not career politicians in our sense. They held office for one year at a time, usually with big gaps between the various offices. If you managed to get appointed to each in turn at the earliest age you were eligible (“suo anno” – in your year – something Cicero was very proud of having achieved) you would be a Military Tribune at 20, wait ten years then do a year as Quaestor at 30, maybe a year as Aedile at 35, another as Praetor at 39 before your consulship at 42. Over those twenty odd years you would be in office for four or five, then you wouldn’t be given another magistracy unless you were needed as a Proconsul in exceptional circumstances (though you were forever after a member of the Senate). In the intervening years you could serve as a military commander or as a civil servant of some kind, but you weren’t at the levers of power. This kind of system is obviously incompatible with the kinds of politicians the US, and most modern governments, cultivate.

cartomancer,

Interesting discussion, as always. A couple of points:

The men who designed the US system weren’t professional politicians as we understand the term. They were, above all, landowners who saw it as part of their duty to participate in public affairs when called upon; afterwards you went back to your land, like Cincinattus.. Holding public office was a duty, even a burden, not a career.

Also, the electoral college and the appointment of senators by state legislators was supposed to ensure that only serious (and presumably sufficiently qualified) men would reach the highest reaches of power, so perhaps that was another way of instituting the cursus.

I thought the men who designed the US system, were slavers who didn’t like the way the English legal system had outlawed (or was in the process of outlawing) slavery and so trumped up ‘No taxation, without representation’, which representation would have done them no good as they would’ve been outvoted by the superior number in England or Britiain, and said fuck it, we might has well try out some of these new fangled ideas and were saved only by the Frenchies who were warring with Britain’s best in Europe and helping defeat those that Britain could spare in the Americas.

I’m not a historian. ;)

Brian English: the revolution was fought by an alliance of disparate interests, who got together to write the constitution after winning the war.

The US rebels took help from foreign powers who had an interest in weakening the british empire — it’s hard to hold territory against a state actor without heavy weaponry, and the easiest way for a rebel movement to get that is from foreign powers (see also Syria).

The brits took help from foreign mercenaries — it’s hard to order your troops to kill your own people.

The Vicar @19:

That’s not how it works. Just as the second law of thermodynamics gives us an ‘arrow of time’ in classical physics, so decoherence gives us the same at the quantum level. It’s the dissipation of the information that was in the original coherent state which leads to our ‘classical’ perception. This is basically irreversible, in the same sense that it is possible for your spilled coffee to spontaneously go back to your cup, but highly unlikely.

@18 “I see no reason to believe we couldn’t get back to a period of strongmen being in power.”

This does make me think of politicians competing in caber tosses or overhead lifts. I’m not sure whether that’d be able to give us any worse results either :(

(Waaaay off-topic from ancient Rome and the modern US.)

The Vicar, #19:

A few things. The time-reversal symmetry of classical physics (Newton, Maxwell, etc.) is a feature of QM too (or I suppose just about any fundamental physics you care to name). So, how you could get an asymmetric arrow of time out of that is still a basic logical issue for all of those theories. If you have some physical state, the dynamics makes no distinction about some other state which is five minutes in the future of the original state or five minutes in the past of it. There is nothing at all in it which even hints at time-asymmetric phenomena like entropy increasing or the fact that you can remember the past and not the future. So you need something else.

But first, be careful to note exactly what is meant here: the difference is not that the past is predictable (or retrodictable) and the future is uncertain. One aspect of it as I just said is that you can with some degree of accuracy remember/record anything about the past, while you have no such access to information about the future. You don’t remember what you’ll have for lunch tomorrow, and there are no records (like receipts, dirty dishes, diary entries, etc.) about what anybody else will have for lunch tomorrow. Indeed, the second law seems to suggest that things work out okay when we do predictions (probabilistic or otherwise) of the future by just evolving the dynamics, because it’s clear entropy increases which is what we wanted. So in some sense you’re on better footing there, not worse, or at least you’re not forced to confront the problem because that seems to be working alright. However, taking the same approach for retrodictions (probabilistic or otherwise) cannot work, because it seems to be saying entropy also curves up to the past, which we have every reason to believe is false.

A popular proposal, defended by folks like David Albert (and I guess a few decades ago by Richard Feynman), is that in addition to whatever the fundamental dynamics may be, there is another law of nature called “the past hypothesis,” which describes the world as having a certain very low-entropy state at some time in the distant past. Conditional on that, all of the probabilities you’d want for thermodynamics, statistical mechanics and the rest will fall into place. A very low entropy past state is also what we actually see in Big Bang cosmology, which is good news because then it looks like everything hangs together fairly well.

Whether any other sort of proposal would work is I guess an open question, but the uncertainty principle and CPT and so forth will not get you there. The numerous time-asymmetries in our everyday macroscopic experiences are not accounted for by anything like that. Even for something as simple as smoke spreading out into a room from a burning cigarette, we think it didn’t start out diffused all throughout the room, somehow found itself miraculously in the cigarette, only to spread out into the room again.

Some people whip themselves up into a confused lather about QM, and this just sounds like borrowing some of that confusion from their inability to formulate a coherent interpretation which doesn’t run straight into the measurement problem, instead of having an actual solution to anything. The assumption that you have done a “measurement” and now you’re uncertain (or the world is uncertain) about what the “results of the measurement” will be is introducing a time-asymmetric assumption by hand. But that isn’t how QM’s linear deterministic equations work, whenever you aren’t doing “measurements,” because they make no funny distinctions about you making measurements at one time and waiting around for the results that you’ll get in the future.

So the question is still what the hell is really going on and how can we make sense of that, as opposed to what would happen if you let yourself cheat by supposing the dynamics are constantly violated because they care so deeply about you and your measurements. (Maybe another question to ask is when the hell are the dynamics actually doing anything in the theory and not being interrupted by “measurements” or “observers” … or are they just for show?) Anyway, as I said, you can get by just fine making predictions in classical mechanics too — it will give you increasing entropy in the future with no appeals to quantum weirdness or anything of the sort — and you’ll still run into the same types of problems in QM once you consider what to say about retrodictions.

(Not quoting because this is, after all, a digression, so I’m trying to keep this a little shorter and easier to skip for those not interested.)

@#29, Rob Grigjanis

That would be a very good objection if I had said “quantum physics says we can reverse time and return to the initial state of the universe”. Unfortunately, I went out of my way to point out that it does not say that, so your point is irrelevant.

@#31, consciousness razor

Actually, the suggestion is that artifacts of the future exist but are in a form we can’t interpret properly. Under this interpretation, if I have a ham sandwich for lunch tomorrow the artifacts would take the form of the ham sitting in the grocer’s deli case, the loaf of bread sitting in my kitchen, the mustard in my refrigerator, the arrangement of finances which cause me to have the money which will eventually be used to pay for the ham, the arrangement of my schedule which will cause me to make a trip to the store during the morning, etc. etc. etc. The universe, in other words, is arranged so that my future ham sandwich is essentially inevitable, even though we are not equipped to determine this fact, and a time-reversed historian (if such existed) would look at our world at the present moment and say “ah, that person there had a ham sandwich for lunch tomorrow, just look at the evidence”. True, we have no memories in our brains about it, but saying that something isn’t inevitable because the idea of its inevitability is not in a human brain somewhere strikes me as more a religious argument than a scientific one. Events in the macroscopic world which are reliant on things so small that quantum weirdness™ requires that they be expressed as probabilities are very rare — even something as large as a single cell is too big for the probabilities not to be smoothed out, so that when it comes to things like human decision-making (which involves fairly large chunks of the brain, and I’m-too-lazy-to-calculate-how-many-but-it’s-a-lot cells) you might as well drop quantum modeling entirely and pretend that the operation is deterministic.

@ 8 Marcus Ranum

I watched it as a boy when it was new. To this day, I’m traumatised by the foetus eating scene. ;-)

I think my parents assumed since it was classical, it was educational, never mind the nudity and gore.

Another thing that needs bearing in mind when we talk about Augustus’s assumption of tribunician power is that the office of Tribune of the Plebs had quite a controversial history over the last century of the Republic. It had emerged in the 5th century BC as a concession to the Plebeian classes following the previous century’s endemic class warfare, but by the late 2nd century BC it had started to be used by ambitious aristocrats to build up a popular following and enact programmes of legislation that favoured the poor. By this time the traditional Plebeian/Patrician class divisions had largely broken down, and did not reflect the wealth and power of the populace. The grandsons of Scipio Africanus were technically still Plebeians for instance, despite coming from one of the wealthiest and most prominent families in Rome.

Prior to the Gracchi (who were prominent in the 140s and 130s, contrary to what some idiot said earlier on) the powers of the tribune had tended to be used in an ad-hoc fashion, reacting to specific personal injustices, but with Gaius Gracchus at least we see for the first time a coherent programme of land and taxation reforms designed to alleviate the increasing unfairness brought about by the economic changes of Empire. What had begun as an office designed to check the immediate abuses of the patrician class through personal intervention (the tribunes were legally sacrosanct – harming them got you exiled or killed – their veto emerged from their literally interposing themselves between people to stop fights) had become highly politicised. It was beginning to be seen as a useful stepping stone in building a political career, especially as – unlike the traditional magistracies of the cursus honorum – there was no limit to the number of times one could be tribune and no prohibition on consecutive terms. So terrified were the Senate of the Gracchi and their novel attempts to use the office for increasingly ambitious things that they declared each in turn an enemy of the state and invoked the senatus consultum ultimum (their ultimate decree, mandating any actions necessary to remove the threat) to have them killed by armed mobs. Further ambitious tribunes in the Gracchan mould followed, such as Saturninus and Livius Drusus. They were seen as demagogues by the senate and champions of the common man by the populus. The truth is probably somewhere inbetween, but they were unashamedly populist and used pressing social and economic issues to mobilise popular support for charismatic generals like Marius in the early 1st century BC. If we’re looking for parallels with Trump then that one stands out quite nicely, I think.

Eventually Sulla took away most of the tribunes’ powers in his reforms, because he saw them as a disruptive force in the state. They were restored soon after, but in the 70s BC Publius Clodius abused them terribly to his own personal benefit (after having himself adopted by a Plebeian teenager so he was technically eligible for the position). After that the Senate bestowed the tribunician power first on Julius Caesar then finally on Augustus for life, in an attempt to prevent further abuses.

The Vicar @32: I was responding to what you actually wrote, not what you imagined I read. And what you wrote was ill-informed arglebargle. This;

is nonsense. Your English and your physics could use some work. Until you’ve done that work, maybe keep your pet ideas in their cages.

silentbob @ 33, I got ‘This video contains content from RLJ Entertainment, who has blocked it in your country on copyright grounds. This video contains content from RLJ Entertainment, who has blocked it in your country on copyright grounds.’I do get your point, even if I don’t fully recall the video. :/

Getting older has an experience point advantage, it also has a loss of memory disadvantage.

FYI, according to Quote Investigator, Mark Twain never seemed to have said “History never repeats itself, but it rhymes.” This is a misattribution that possibly originated in a poem from 1970. The closest Twain came was writing, “History never repeats itself, but the Kaleidoscopic combinations of the pictured present often seem to be constructed out of the broken fragments of antique legends.”

@ 36 wzrd1

Well, I’m sorry about that. I thought it was only us foreigners who were restricted. ;-)

I think if you try this link, and manually scroll to about 42:30, you’ll see what I was on about.

You seem very confused. What sort of evidence would a historian have, in a world which had no asymmetric arrow of time (thermodynamically or epistemically or in any other sense)? That ham sandwich fluctuated out of a high entropy state, as did the person and everything else, if you take the higher entropy states to be more probable in the past as well as in the future, because you assumed a uniform probability over all of the compatible microstates that produce such a macrostate, thus giving absurd microstates high probabilities instead of low ones (but of course you don’t need to assume that). To put it another way, it congealed into an edible-looking ham sandwich, after a progression of states which look more or less like a decaying ham sandwich in reverse, and meanwhile the person eats it after they also fluctuated into a person from a series of states start from something like a corpse. That is, in one way or another, it started out like some rotten-looking thing, and it didn’t start out as a pig and some wheat, which were put together through a whole convoluted set of processes (as was the person eating it) that all along the way increase the entropy of the whole system as time goes by into the future.

We know very well that it doesn’t actually happen that way in the real world, that the person who eventually eats the ham sandwich didn’t fluctuate into the world as some kind of corpse-like entity. (They were once a baby, their whole life they’ve been part of processes that increase entropy, the photographs of them being babies have also aged over time, their other records like a SSN card also aged and got a particular number given the sequence of births in the country, and so on.) The fact that there is merely some definite state or another in the future, which contains some kind of evidence or another about the person eating the ham sandwich (since the info doesn’t simply vanish), doesn’t actually inform you about any of that. Is this sort of bizarro-world historian supposed to take stuff like that for granted or not?

No, that’s not the idea. Determinism vs. indeterminism has nothing to do with it. The fact is that entropy increases toward the future and decreases toward the past. In classical terms, to keep it simple, systems tend to go from very, very, very tiny regions of the phase space to much, much, much larger regions of it. The simplest explanation that might occur to you is that things end up in higher-entropy regions because those take up almost the entirety of the phase space, and they don’t tend to go to lower-entropy states because wandering around aimlessly through it will typically not lead to something which takes up almost none of the total volume. But then the question is still how any of this relates to the direction of time, if you don’t just postulate that things started out in a low entropy state. It makes no difference whether your mechanics tells you systems evolve deterministically or indeterministically, because the issue is that what none of them by themselves do tell you is that systems go from lower entropy states in the past to higher entropy states in the future.

I don’t understand why you’re putting any of it this way. For one thing, all macroscopic phenomena rely on microscopic degrees of freedom, whether or not those behave deterministically. Our talk about the entropy (or temperature, etc.) of a macrostate deliberately ignores the numerous different microstates that correspond to that macrostate. Suppose you’ve got a table. If a single electron in the table had been a bit to the left (or if it were different in whatever insignificant way you), then macroscopically it would be an indistinguishable table, because there are 10 to the power of a fuckload of other things going on in that table’s microstate which remain identical under such a change.

So you’re leaving out that kind of detailed information, because for most purposes you don’t need it to scientifically study all of the regular and predictable behavior of things at the scale of macroscopic objects like tables or things with temperatures, which we know empirically go from lower entropy to higher entropy and not because the dynamics themselves force that conclusion. The phrase “regular and predictable” above is not to be understood as “deterministic” necessarily, but in the sense that you can assign a set of probabilities, like you would in classical statistical mechanics, which represent what is being predicted in a precise-enough way to do the scientific job at hand. Statistical mechanics, as the name suggests, always deals in probabilities, even though classically it’s typically thought of as being a contribution to a more fundamental deterministic theory like Newtonian mechanics (but not necessarily, and at any rate you can have deterministic QM theories too, so this is all utterly beside the point). If doing that is to “pretend the operation is deterministic,” then I have no idea what it would look like to pretend it’s indeterministic or to really seriously think it’s indeterministic. How is it operationally different?

One way of expressing the arrow of time problem is that the naive approach is getting the probabilities all wrong, in even the most boring and easily-citable cases. (Because, for example, the probability that I used to be a corpse which fluctuated out of the chaos is in fact not fantastically high, compared to the probability that I was a baby in a world which had a lower entropy.) And it doesn’t make sense that you’re trying to reconstruct this in a way which claims human decision-making (or whatever it may be) is actually being treated by anybody as if it’s recognizably working according to some deterministic process that anybody can actually articulate (much less use). Who does that, and what are their deterministic equations for it supposed to be?

BTW as I understand it, whoever occupies the White House has the power to listen in on all electronic communications in America, including those of his political opposition.

Am I wrong in this?

re@40

NSA to multitool. Yes. you. are. wrong. [EOM] (keep talking for us to keep occupied. shhhh)

Commodus murdered people in staged gladiatorial matches. Trump fires people on reality TV. This may be regarded as progress.

multitool@#40:

It’s complicated. The problem is not accessing the communications, it’s finding it. But, given a target, yes, they can dredge up a great deal. Here’s why it’s complicated: anyone who works for those agencies, with the right clearance, can dredge up the stuff. So, it could be someone trying to support the regime, or it could be someone trying to take it down. A lot of people don’t realize that the NSA is sort of like a multi-edged knife: you can wield it in any direction you like, but it’s going to do unexpected damage as often as not.

The way I think of it is this: the current police-state has taken significant steps to aggregate power into a single set of reins. The problem with doing that, is it makes taking control of the reins of power even more attractive for the wrong sort of people. Basically, the clever idiots who built those systems have built the tools for their own subjugation.

multitool @ 40, you are wrong.

Google Richard Nixon.

Eavesdropping on the political opposition is a no-no, eavesdropping on suspects with a warrant from the rubber stamp FISA court is OK, but the POTUS isn’t the one listening.

The NSA does and frequently, what is monitored is never heard by human ears. Text to speech processing and keyword flagging is what goes on most of the time.

Marcus Ranum @ 43, I agree completely.

Such capabilities are indeed a dangerous double edged sword.

When used for good, they’re a powerful tool to combat crime and especially terrorism, when used for ill, they’re monstrous tools of oppression.

The trick is finding a balance or doing without them and accepting the risk.

Considering each risk, that of terrorism and the risk of oppression by power hungry individuals or groups, I’d rather do without those tools.

That’s especially true since we’ve yet to prevent a terrorist attack using these tools.

Worse, with standard risk assessment calculations, with precisely zero return on investment, we’ve mitigated no risk of terrorism, while increasing our exposure factor of an abuse of these tools significantly.

In short, we tried to mitigate a risk and instead created a greater risk.

When I asked if the president ‘has the power to’, I am not talking about laws or accountability. Those things aren’t going to exist for this regime.

Mostly I mean if the president packs the entire federal government with obedient flunkies does he have access to pretty much every electronic communication.

I think the Democratic party should start seriously considering Tor for everyday use.

My landlord used to say: History is the most useless discipline. People don’t learn from history anyhow.

Well, Nixon had his “plumbers” wiretap the DNC headquarters at the Watergate office complex.

Something quite odd, as he was winning by a long shot.

The end result was articles of impeachment and his resignation, as well as 48 guilty verdicts, many being Nixon’s top officials.

Additionally, the NSA is part of the DoD and military service members are trained to disobey unlawful orders.

As for TOR, not worth it. The TOR network was broken a long time ago. Own enough exit nodes, own that network.

If one wants to be really secure, one uses OTP cyphers.

My understanding is one or more of the dummie’s staffers feel for a phishing attack, suggesting the flaw wasn’t with the comms links, suggesting TOR or OTP on those links could be a case of locking the door and forgetting about the Windows. Not useless, but nowheres near a solution.

And if initial entry was by a phishing attack, staff training should be fecking high up on the list of actions.

Alas, phishingg, especially spear phishing has been highly effective in many breaches.

This, despite annual refresher training on information security. :(

>If one wants to be really secure, one uses OTP cyphers.

Well thanks for that tip, I learn something new every day.

But, Nixon was brought down by a Democratic Congress, which we don’t have today.

As for the Military, I have been told that the whole top tier are zealots now. It’s a cultural shift. I don’t think anyone refused to do torture or anything else illegal for the Holy War in Iraq. They might disobey the Trump administration, but I’d have to be pretty desperate to bet my life on it.

It’s one thing to monitor terrorists traffic, it’s a totally different game to monitor political opposition traffic. Therein lies the path to civil war.

As for the military refusing to torture prisoners, there were indeed instances where service members refused to participate. Those instances were quietly swept under the rug. That aside, most of the torture was run by the CIA.

Even the Omega 13 won’t help us now.

@47

Yah cause it is different this time!

uncle frogy

The NSA happily followed the order to wirelessly tap some individuals without a warrant, and to collect metadata on everyone without a warrant.

One person rebelled against this; he’s now in exile, seen as a traitor by many. The rest of the organization just kept on going.

Actually, no tapping was done, metadata was collected. Tapping and full captures of network traffic was only done with a warrant from the FISA court.

The one person was and remains a traitor for one simple reason, rather than address the issue with Congress, as congressional oversight is a duty of Congress or even the domestic media, he went immediately to foreign media.

Nobody was prosecuted for The Pentagon Papers.

When one signs the NDA for classified data, one is briefed on what will happen if one divulges to uncleared persons and especially to foreign persons.

I’ll even say that Manning is in the right place. Alas, Manning should have had a commander down throughout the chain of command as company, as when a person is flagged for deleterious personnel action as Manning was, clearances are terminated immediately. That’s to prevent just what happened. Pure dereliction of duty that should have resulted in a reduced sentence.

wzrd1:

<snicker>

<giggle>

(Yeah, I know you speak of a specific and not in general… but. Still funny)

PS

Have you considered that getting actual data could help provide compelling metadata?

(You can trust the NSA to the degree you can expect them to be unable to keep any untrustworthiness hidden)

I trust the NSA. About as much as I trust any spies.

That’s why Congress provides oversight.

But, going to a foreign media organization first, rather than attempting to address what one feels is wrong is not a proper first step, it’s an absolute last recourse.

As I said, The Pentagon Papers were published in the US press, were addressed and reprinted in Congress and the problems addressed and nobody ended up in legal trouble.

Oh, the military tried to make trouble for the paper, but that went precisely zero meters in court.

wzrd1:

There’s one sense of oversight, and there’s another oversight. You think one is inapplicable?

(Moral ambiguity and pragmatism go together)

What, are you an omniscient observer? You know what you are permitted to know.

Appeal to consequences is not a valid argument.

—

Shoulda left it at that.

(Because it’s all you have)

as for mr S. going to “foreign media” I think it was a judgment call as to which was the most assured way to make the documents public with a reasonable eye to the consequences to himself. In an Ideal world I would agree it should have been a last resort but he had the example of an E-4 in prison for essentially the same thing to go by besides the political climate and the “new security laws” that were not present back in the 60’s or 70’s..

even so the release of all of those documents have made hardly a ripple in policy or procedure and things for all we know are just as they were before the release.

the hew and cry has been rather about the security breach and not the truths revealed.

slowly we slide

uncle frogy

Not consequences, but that the results do speak for themselves. As a result of the US publication, significant oversight did occur.

As for me knowing what I am permitted to know, I once ran into an automation created file directory while preparing a briefing for our commander.

In that directory, I found transcripts of telephone conversations, of which I read one specific conversation – my “morale call” home with my wife. We knew that our telephones were monitored, which began in earnest after a couple of intentional fratricide instances.

The only thing that was unexpected was that it was automation created, unmonitored by humans and accessible to me.

Other automation created directories had excerpts from social media, where mentions of unit activity was mentioned. That, initiated after some movements of units was mentioned, when those movements shouldn’t have been mentioned. Those did get human monitoring and annotation, including if a service member was counseled over giving too many specifics.

So, I happen to actually know a great deal more about what is and was collected than most. I just won’t discuss details.

The military gives very little expectation of privacy for its members, for very good reasons.

In those very specific instances (others, I’ll not discuss), to hopefully prevent a hand grenade being thrown into a commander’s tent or to avoid having a reception committee waiting for a team’s arrival and a 21 RPG horizontal salute presented to them.

That said, the notion of that wholesale metadata gathering was and remains horrifying to me, as the potential for abuse and harm is great, while the risk it was to mitigate against, quite low. It fails any calculation of risk analysis.

I also believe that the FISA courts need greater oversight and accountability, as they’re largely rubber stamp courts at present. Unfortunately, we don’t have a Constitutional framework that supports that, which gives me concern as well.

Bad things happen when oversight is impossible, as there are then no checks and balances.

I don’t trust spies, but I do recognize the necessity for them. Spies keep everyone honest, when nations are interacting.

wzrd1, fine.

Corollary: either you deny such things as “black ops”* exist, or you acknowledge you merely trust that they are justified, or you claim you can determine their circumstance and therefore their justification..

(Obviously, an inference I make is that you think this entire episode is transparent–dust has settled–so that you can judge it knowingly. Informative.)

—

* History records

John Morales @ 63, Congress has a SCIF to review classified information, they have intelligence oversight committees as well.

Service member also leak information to the leadership in Congress and to the press, not to mention memoirs. Not much stays buried for long, if something is amiss.

unclefroggy @ 61, Manning was an E-3. Everyone from his battalion commander through his S1 and S2, as well as his supervising NCO’s should be in adjacent cells. Dereliction of duty, as access to classified information is to be immediately terminated upon flagging for deleterious personnel action. Manning was pending separation for cause, due to behavioral/disciplinary issues.

That said, nothing Manning released was news. A bunch of men with AK’s and a RPG was running and gunning all morning against US forces, a camera crew stupidly approached them and got caught in the crossfire (review the full footage, not the cropped and edited version).

Diplomats loathe each other, attend one embassy function and that’s obvious.

Since we tend to prefer not misgendering trans people here, it seems only right to point out that Chelsea Manning identifies as female now, so should probably get she/her rather than he/him.

wzrd1@#56:

Actually, no tapping was done, metadata was collected. Tapping and full captures of network traffic was only done with a warrant from the FISA court

I just happened to drop in and saw this juicy nugget of wrong. I’m not going to unroll the whole thread, but it’s wrong because you’re accepting a story that “metadata” does not include the message data. That’s actually not how the system works: the system collects everything, skins some metadata out, does automated analysis on the metadata, and the government has defined “surveillance” as only happening when human eyeballs see data. So, the system “only works on metadata” except that it really doesn’t. In principle examination of the full data requires a warrant from the FISA court, which has never refused a warrant — so for all intents and purposes — the warrant doesn’t mean anything.

If you were to think about it for a second or two, you’d realize that the only useful system is one that works as I describe. Because, otherwise, you get a metadata match and – then what? The message has flown past on the internet – you can’t go get it back. The only system that works at all is one where the data is all kept for future examination but is defined as “not surveilled” because the only thing that “saw” it was a computer.

We can also make some pretty accurate inferences as to how long the system keeps certain pieces of data: the FBI was able to pull up years-old text messages and emails from David Petraeus and his girlfriend.

Besides, there are several technically credible witnesses who have described the bulk capture systems in detail, including the brand-names of the products (which I am familiar with) and the network architecture of the back-haul (which I am familiar with) Look into what Klein and Binney have described.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Room_641A

wzrd1@#64:

That said, nothing Manning released was news. A bunch of men with AK’s and a RPG was running and gunning all morning against US forces, a camera crew stupidly approached them and got caught in the crossfire

Of course it was news. Prior to the release of the video, it was not known that the camera crew were killed by “friendly” fire. And, the clarity about the rules of engagement was important — most people did not realize that you had gunships a mile away looking at crappy video and going “do you see a gun?” then lighting people up and laughing about it.

If you’re maintaining that’s not news you’re downplaying what happened. Why would you do that?

PS – they did not get “caught in a crossfire” they got targeted and shot to pieces. That’s also news. Because the story prior to the release of the video was what you said: crossfire. The story changed to “deliberate” friendly fire which certainly fits my definition of “news”!

wzrd1 seems to be committing the No True Illegal Order fallacy.

He also forgets the whole Arab Spring thing, which was sparked in part by Manning’s disclosures.

Marcus Ranum (multiple entries),

Yeah, I’m familiar with the products, models and capabilities of the hardware as well. I am an information security type, who also worked for a long time on the civilian side as a systems engineer. Big Iron and I are old, old friends. Ya outta see my lab sometime, plus my home production network.

The NSA data center in Utah looks to make one fine gaming server farm too. ;)

cartomancer @ 65,

As for PFC Manning, I tend to group gender by time frame identification, so feel free to kick me back into the 21st century. I liked it here until the last election. :/

More seriously, yeah, I do tend to group things that way, hence the error. Thanks for the catch, still working on that one and I really don’t intend offense.

numberobis @ 68, I have no idea what you’re speaking of. An unlawful order is an unlawful order, I and my team have had badly framed orders that we refused to obey as stated. I’ve even stated outright, “Yeah, that ain’t gonna happen, we’re not going to prison for you” and documented the incident when we returned to the FOB.

We also tended to release those we captured, once we learned about the torture that was a thing at the time. We couldn’t handle that on our conscience. Strangely, we asked for the detainee’s word of honor to not return, lest next time, he does get taken in and only a few times did we see that individual again. But, there was some confusion as to *why* we invaded Afghanistan and an iPod video of the WTC attack and collapse and the listing of my cousin’s name, who did die in the north tower silenced any complaint and tended to garner support.

Learning about a culture and the history of that culture in the region one operates in is rather useful, it helps build common ground. From there, one can build further.

Are you familiar with CENTAUR? We have something very similar where I’m working now, it came in handy finally fully capturing the malware used by a foreign state actor who penetrated our network. Quite a novel approach too, using notepad, RDP and buffer. Reminded me of EICAR.

Friendly fire means one’s own forces are engaging one. That press team was not part of friendly forces or “enemy forces”, they were independent in operation, wandering about at this own peril and they were with that group of armed me, who were engaging US forces all morning. An RPG is a very distinctive thing, once one’s had one fired at oneself a few times. Get a few ribs broken from fragments thrown by one’s detonation, yeah, I recognize it instantly.

Ever break ribs in line with your axilla? I don’t recommend it (my ESAPI plate shifted upon fragment impact, fracturing three ribs). Amazingly, I don’t have nightmares over that one.

I’ll also say, friendly fire isn’t. Ever.

But, in that reporter’s position, I know that the reporter’s team and reporter were briefed on risks and who not to approach, under combat conditions especially.

I’d not blink an eye on pushing the fire button myself under those conditions and I’d not lose sleep over that.

Wars are messy things, frankly, I prefer them that way. Maybe we’ll try to not keep having them! Gulf War I only encouraged Gulf War II, as the first one was soooo precise, due to what was released to the press. Precision bombing, no collateral damage (OK, minimal).

I’d prefer people to see what a JDAM does to the poor saps next door to the terrorist *and* what the terrorist did before, let them gauge which evil to prefer.

And assess how our lower yield devices are, dropping fewer houses.

I’d close the documentary with the time I relieved our designated marksman, as he was very, very fatigued, his assistant injured by a sniper, three men also injured by said sniper. I took over, being qualified on the system and rotating through to replace a junior team member on R&R (I did that, despite my rank, to retain my skills *and* train my replacements by their filling my position briefly).

I rushed a shot at the sniper’s last location, had a clear shot, perfectly framed and adjusted for conditions and fired.

Then, reached out to catch the bullet and bring it back, as the face turned toward my scope.

A kid not much older than my eldest grandchild.

The round struck, I’ll not describe the effect, but it’s why I drink myself to sleep each night. The sniper immediately surrendered, it was his kid brother, who stalked out of the house against both elder brother’s instruction and mom’s orders.

Elder brother surrendered immediately, out of concern for his deceased brother. We all ran in to check out the kid, hoping.

We cleaned him up, part of the team searched, cleared and restrained the elder brother.

We cleaned the child up as best that we could, using up our own drinking water, wrapped him inside of my own poncho and transported him to the village and presented him to the village elders.

Then, I had to get between an enraged mother and her eldest son. Apparently, dad did pretty much the same thing and ended up killed, he was the “man of the family”.

We still have a “flower fund” going toward that family and the eldest son never got processed far, he got sent back home. That took a *lot* of favors.

It’s one reason I can’t fire at military silhouettes today and require circular targets of the CMP program.

All, because I rushed a shot.

I’d want everyone viewing to know that memory as well.

Would that we had media that could transmit emotions and memories. Wars would end immediately.

The memory of “I fucked up and a kid that I literally viewed as my grandchild was murdered by me” would be a wonderful thing to impart to the war willing, wouldn’t it?

Now, excuse me while I finish off the 1.75 liter bottle of spirits I purchased a few days ago.

I go through two a week.

As for Arab Spring, that was a small spark, in a basket full of sparks. Bahrain had protests nearly every week, as one example, nothing changed (although, there is a bigger issue there, a religious one. Thankfully, nowhere near as bad as the UK, not all that long before the American Revolution.

I’m greatly enamored of a old commercial during the Vietnam War era, two old farts, obviously Presidents, who “fight a war” via a fist fight.

As an old soldier, I’ve always loathed war. Experiencing two, I loathe it more.

At times, considering whether or not to continue existence.

But, responsibilities are duties, just as serving on a jury or voting are duties. That overrides that brief, defective thought.

Soldiers, Marines, Sailors and Airmen aren’t robots, they’re people. We served for various reasons, those who remain as a career, even in the reserve or Guard are there for the same reason, duty to protect and support a nation.

We’re far from perfect and know it. We do the best job that we can do under utterly imperfect conditions, in the extreme.

As people, we encompass the entirety of our national existence. From far right to far left, from entirely centrist through various shades. From batshit crazy through somewhat sane (see Sigmund Freud). *

And life, like people, is complicated. **

*A joke, Saint Sigmund was far from sane, let alone right on many, many, many things. He was slightly more right than the rest of the field was utterly wrong.

**I’ve also withheld many things, out of considerations for the reader. Trigger warning pales on some things, which are unclassified.

Although, one individual mentioned “black operations”, somewhat dismissively. Suffice it to say, I have a rather decent, or perhaps, indecent memory of such things.

Good night. Weather systems, old injuries and new ones are taking a toll. My newest superpower, taking its own toll.

Barometer man, at your service!***

***Seriously, my calves have been spasming after a recent injury, catching my wife, not long after abdominal surgery. I suspect it’s L4-L5, but the insurance company…

Now, spasms have extended to the arches of my feet and semi-random fore thigh regions.

And work beacons tomorrow…

Fortunately, it’s my “Friday”.

Lot of roman history here. The second half of Tuesday’s “Kaiser Report” essentially predicts Trump’s assassination. Is he gonna turn out to be the good guy?

wzrd1, #69

It’s not an entirely straightforward issue. Some trans people are happy to use different pronouns to describe themselves before they started living as their preferred gender, some are not. I’m certainly no expert, but I supect most are not, at least in English-speaking countries. I guess it depends on whether they view the pronouns as markers of intrinsic personal identity or conventions of social presentation. On the other hand, virtually nobody will get upset if you use the pronouns for the gender they present as now to describe them before they started doing so, where doing the opposite can be quite insulting and demeaning to a lot of trans people. So, all things considered, the convention of using their current pronouns unless they’ve told you they prefer otherwise for historical usage seems a sensible one.

Since we’re on a thread about Roman history, though, I will note that problems can arise with this convention when we are unsure whether someone was in some sense identifying as a different gender from the one assigned at birth. The Emperor Elagabalus, for example, was said to have lived as a woman and offered vast rewards for anyone who could provide him with female genitals through surgery or magic, but we don’t generally refer to Elagabalus as “her”. The problem here is that Elagabalus might have been transgender (not that the Latin of his day would have articulated the concept as we do), but deeply misogynistic and homophobic slurs against despised Emperors were a commonplace in the rhetoric of Imperial history writing, so it is much more likely that this is another nasty piece of invention. The story comes from Cassius Dio, who is not exactly discerning in his reporting of salacious palace gossip, and it is probably just an allusive metaphor for his ineffective rule and supposed hedonism (he was a teenager, and Romans tended to have a very strong dislike of being ruled by people younger than them). So we’re in a bit of a bind here – using feminine descriptors for Elagabalus might very well be buying in to Roman transphobia.

wzrd1: to avoid having a reception committee waiting for a team’s arrival and a 21 RPG horizontal salute presented to them.

Well this has my attention! Can you elaborate?

It sounds like a whole team of US soldiers deliberately shooting at another team. Does that really happen?

No, some idiots would post on social media their travel route, origin and destination. Others would have their spouses mention their movements, both not thinking that the adversary was also monitoring social media.

So, a few times, there were indeed well armed reception committees, IED’s and other unpleasant surprises.

So, the DoD began monitoring for that as well, having the service member stop blabbing so much and altering now compromised operations.

Blue on blue, it happens on occasion, unit in the wrong location, miscommunication, much easier travel making the unit extremely early to their destination. It’s a lot less than in previous conflicts though, due to much better communications, special designators and GPS.

This might be somewhat late, but I have a question @ cartomancer and others who are probably much more knowledgeable than me about the roman republic: According to Wikipedia. the tribune of the plebes was capable of introducing legislation before the plebeian council, which (after a reform) used “tribes” rather than the tax classes of the commitia centurita. Is that correct or is the Wikipedia article wrong ( thoughIt also mentioned that before the Gracchi, very few people tried to use that power to the fullest extend)?

Actually, yes, the original legislative power of the tribunes of the plebs was to convene and introduce legislation before the concilium plebis, not the comitia centuriata (I got that one wrong in my eagerness to give examples of how democratic participation was rather limited in the Roman constitution). They were, however, able to use their veto in the comitia centuriata and had a right to speak on the legislation under consideration there. In practice they often had to defend the legislation they introduced to the council of the plebs in the centuriate assembly when politial opponents tried to repeal it – as Gaius Opimius and the senatorial faction tried frequently to do with Gaius Gracchus’s laws (as well as recruiting their own tame tribunes to stymie him in the concilium plebis). Laws concerning military matters had to be proposed through the centuriate assembly though.

From the perspective of later Roman writers it was only when tribunes such as Gracchus started using their powers to enact serious legislative programmes that the stability of the state started to break down. Under the principate the Gracchi were seen as the ones who triggered the inevitable collapse of the Republic by challenging the Senate and their aristocratic control.