If you want a text version of this article, and description of the tables in it, click here.

For some time now, I’ve had a basic history of climate science more or less memorized. It’s useful to know what we knew and when we knew it, particularly when talking to people who still believe long-debunked misinformation like the idea that the theory of man-made global warming was a post-hoc creation to explain observed warming.

For that entire time, I have been wrong about who first discovered the role that carbon dioxide plays in Earth’s climate.

My go-to narrative generally went from Fourier in the 1820s, to Tyndall in the 1850s and 1860s, to Arrhenius in the 1890s and early 1900s, to Keeling in the 1950s and 1960s. It’s a decent map of key moments in our understanding of CO2 and the global climate, and an effective demonstration of the ways in which the theory was developed, and how it was -and is – a predictive theory that has been supported by a vast body of evidence since its inception.

With simplicity, however, comes inaccuracy. I do not subscribe to the Great Man theory of history – none of the men listed above made their achievements alone, and all of them built on the work of people who had gone before. They were part of communities of people working to understand the universe. The act of singling them out to create a simple, punchy narrative necessarily hides the work of countless other people that contributed to the publications that “history” chooses to single out.

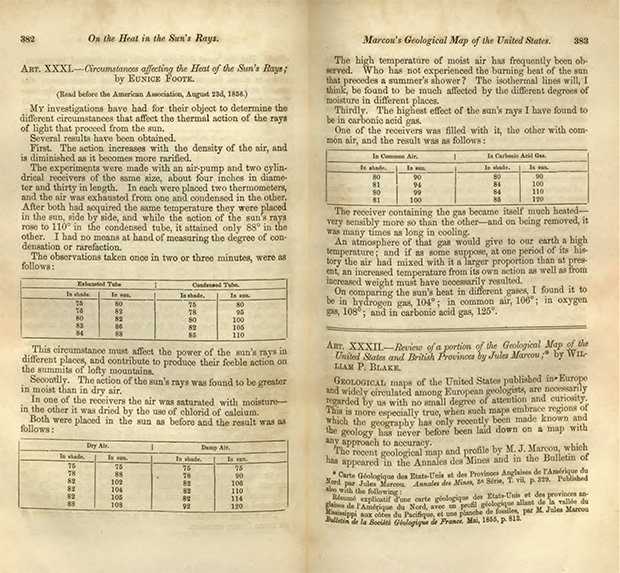

My error, however, goes beyond this necessary over-simplification of history. The reality is that Tyndall, for all his many accomplishments, should not occupy that spot in the story. That place rightfully belongs to one Eunice Newton Foote, who published on the role of CO2 in our climate in 1856 – four years before Tyndall did. Whether through ignorance or malice, Tyndall did not reference her work when he published his own work on the subject. As my discussion of communication between scientists implies, and this linked abstract notes, “From a contemporary perspective, one might expect that Tyndall would have known of her findings.”, particularly since much of that communication is centered around such publications.

Beyond her work as a scientist, Foote was active in the movement for women’s suffrage in the United States, and was a signatory on the Declaration of Sentiments from the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention.

For a woman like Eunice Foote—who was also active in the women’s rights movement—it could not have been easy to be relegated to the audience of her own discovery. The Road to Seneca Falls by Judith Wellman shows that Foote signed the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention Declaration of Sentiments, and was appointed alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton herself to prepare the Convention proceedings for later publication. As with many women scientists forgotten by history, Foote’s story highlights the more subtle forms of discrimination that have kept women on the sidelines of science.

Foote’s role in history was uncovered by researcher Raymond Sorenson, who published a paper on her in 2011. The greatest service historians provide to us is in their work to sort through the various accounts and records of history, and dig up truths about our past which are so often buried under layers of ego, bigotry, and political power games. In a society founded on science, that lionizes those who first discover new facts about the world, it’s good to see recognition of a woman whose efforts were wrongly ignored for so long.

Another small error, just a typo really, and it shouldn’t confuse people since it was easily spotted by me and I know nothing about the subject, but Foote was unlikely to be publishing in 1956 and also a signatory of the Declaration of Sentiments in 1848 – that would mean her adult, productive life spanned more than 108 years. Also, since Tyndall published in the 1850s and 1860s, it was clear from what you wrote that Foote’s (relevant) publication must have been 1856, not 1956.

Obviously a typo, but I thought I’d mention it in case you wanted to correct it.

(I originally posted the following elsewhere — but seem to have misplaced the reference — shortly after the Grauniad’s short article (Sept 2019).)

An unsung climate hero comes in from the cold (quoted in full (too short for sensible excerpting)):

I have no recollection of hearing of Eunice Foote, and had thought John Tyndall was the first to make the link. Although the proceedings didn’t include Foote’s paper, it was published (not just a summary), and there was even an article in Scientific American about the work.

Interestingly, in the comments, one reader points out that in 1824 “[Joseph] Fourier says the surface of the Earth is warmer than it should be, it must be doing something like a greenhouse.” Also, How Joseph Fourier discovered the greenhouse effect:

The NOAA also has an article about Ms Foote, Happy 200th birthday to Eunice Foote, hidden climate science pioneer.

As the NOAA article (and others) notes, Ms Foote (she is not known to have had a degree) was also an active woman’s rights campaigner:

† Henry clearly thought the situation absurd (Eunice Foote, John Tyndall and a question of priority):

From the NOAA article:

@Crip Dyke #1 Thanks for spotting that! Fixed it.

@blf – one thing to note about Fourier is that the Greenhouse Effect was one of two hypotheses he put forward, the other being the Cosmic Ray Hypothesis, which continued being touted by certain people into the 21st century, due to its political utility.

The idea that the extra heat was coming from outer space, rather than insulation from atmospheric gases, is a compelling one if your paycheck depends on continued emission of those gases.

OT, but this:

is actually a gross oversimplification. Stanton did a lot of the scribing, but the document was written through a group process. She’s often given credit for it since she was also responsible for reading sections out loud and asking for feedback, then reading it again later for verification that the new version was going to be final. She wasn’t even the only person who did this, but from the sources we have, she was probably far more responsible for this particular role than anyone else. But that doesn’t mean that others present didn’t chime in with feedback and proposed wording (and, in fact, they did).

So… “written” in the sense of “scribed”, sure. But not in the sense of “authored”. She was a powerful influence on the final document, and deserves great credit. But that’s not the same as saying she wrote it herself.

Thanks for this post – very informative, interesting and the first I can recall hearing of Eunice Foote too. Great to know about her and will share.

PS. Sorry for the delayed resposne here, saw and meant to read earlier but then got distracted.