Content warning: Misogynist Magic

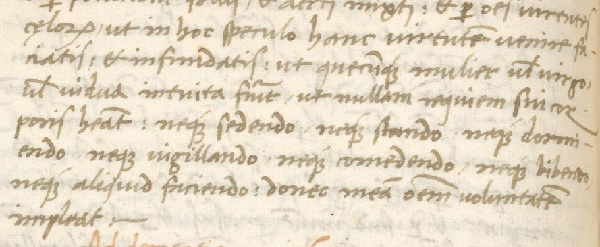

Back on that Latin shit. I was translating a spell and one particular scribal abbreviation was giving me the business. It looks like “heat” with an arc over it. I couldn’t easily track it down on internets, was looking for second opinions. On the other hand, I think I’ve gotten a lot better at the transcription / de-abbreviation process than I was. Check me out…

Including any grammatical and spelling mistakes of the original writer and likely adding my own, here you go:

“…et per omnes virtutes celorum , ut in hoc speculo hanc virtutem venire faciatus : et infundatis : ut quecunque mulier ut virgo , ut vidua intuita fuerit , ut nullam requiem sui corporis he^at : neque sedendo , neque stando : neque dormiendo , neque vigillando , neque comedendo , neque bibendo , neque aliquid faciendo : donec meas omnem voluntatem impleat :- ”

This is a spell to dominate women, because Renaissance wizards were incels. Lacking any Latin skills, bouncing between wiktionary and google search and google translate, this is my rough interpretation of this part of the spell, slightly rearranged grammatically for ease of reading:

“…and by all the heavenly powers, as bound and established in this mirror: Whatsoever woman observed within, be she virgin or widow, shall not rest her body (he^at), shall not sit, not stand, not sleep, not see, not eat, not drink, not do a thing, until all satisfy my will.”

So what is the Latin “heat”? Based on the usual way these abbreviations go, “hemat,” but what would that mean here? This grimoire often reduces compound vowels from Latin to a single letter, for example turning ae into e, like in “celorum” from the first phrase. The closest word then that I could find was “hiemat,” which would turn the phrase into something clunky like “shall not rest her body though it be winter.” Also if this was a dip into Greek, it could be something to do with blood. “Shall not rest her body though it bleeds.”

What do you think?

–

It would be a slightly odd way to contract the word, but for the sentence to make sense it really has to be “habeat” (third person singular present subjunctive of habeo, habere) – “let her have no rest of her body…”

Cartomancer comin’ through! I’ve been putting together my work for possible publication, and was wondering for a consultation like this one – where I did my best before I asked for the second opinion – what would you charge per word? I don’t feel comfortable leaning on people over and over again. And if I’m not furloughed from my job next week, I can afford to pay.

–

The “tus” ending makes no sense. However, it looks like the same ending as “infundatis” (2nd person plural present active subjunctive), which would make it

“may you [plural] cause that power to come into this mirror and may you [plural] infuse [that power in the mirror]”

Also, IMHO, “speculo” should really be “speculum”, since it’s into the mirror, not within the mirror.

Allison – I did mis-transcribe faciatis, but speculo would an error of the original text, and I’m going to leave those intact in my final presentation of this material. I don’t want to pretend that I have better knowledge of Latin than the magical PUA that wrote this in the fifteenth century. And while I’m surely changing some meanings in translation, I think it would be better for a lay audience to be able to read it easily than to have perfect accuracy. It’s the judgment I’m going with for this project, at least.

–

Yes, the original text does have “speculo,” and I don’t think it was a misprint.

I have a theory as to why it’s speculo and not speculum. (This theory’s for free!)

In classical Latin, “in” is the only preposition that can use two different cases. (In contrast to, say, Russian or German, which have a whole bunch of them; Russian has some that use three.)

“in” with the accusative (“speculum”) means “into”, whereas with the ablative (“speculo”) it means “within.” (More or less — different languages use prepositions differently.)

As Classical Latin became Medieval Latin, some irregularities got regularized. My guess is that one of these irregularities was having “in” use two different cases, and they started treating “in” like all the other prepositions and just used the one case (ablative — “speculo”) for all uses of “in.”

Also, I think that the fourth from the last word should be “meam”, not “meas.”

Why not? I’ll change it in my notes, leave it on the blog post to reduce confusion. How would you like to give my work a once-over when I’m done? I’m fishing around for rates.

–