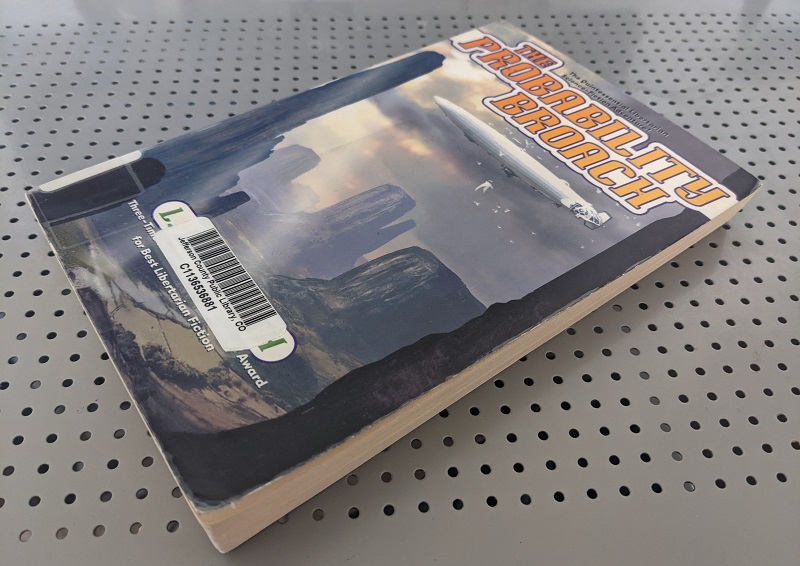

The Probability Broach, chapter 1

It’s time to plunge into The Probability Broach. The opening narration tells us that it’s July 1987, in Denver, Colorado.

Every chapter opens with a fictitious quote setting the scene. Here’s how the first chapter begins:

…would cease operations early next month. In a joint press release, executives of the other networks regretted the passing of America’s oldest broadcasting corporation and pledged to use the assets awarded to them by the federal bankruptcy court to continue its tradition of operation “in the public interest.”

In a related story, TV schedules will be cut back by an additional two hours in eighty cities next week. Heads of the FCC and Department of Energy, officially unavailable for comment, unofficially denied rumors that broadcast cutbacks were related to recent media criticism of the President’s economic and energy policies.

—KOE Channel 4

Eyewitness News

Denver, July 6, 1987

As I mentioned earlier, Atlas Shrugged spends almost all its run time in the “regular” world, with just a brief sojourn in the capitalist utopia of Galt’s Gulch. The Probability Broach does the opposite. It starts out in the “regular” world, but spends only a short time there before switching tracks to its sci-fi libertarian utopia, the North American Confederacy, where it spends the rest of the story.

Both Ayn Rand and L. Neil Smith are trying to pull the same trick on their readers. They portray a dystopian world of repressive government and economic decay, and they want you to think it’s our world – either now, or in the very near future if we don’t adopt those authors’ politics.

In reality, these authors’ so-called regular worlds are just as fictional as their utopias. They’re not the product of any real or proposed set of progressive policies. Rather, they’re a pure conservative straw man about what would happen if liberals took power.

The narrative starts:

Another sweltering Denver summer. A faded poster was stapled crookedly to the plywood door of an abandoned fast-food joint at the corner of Colfax and York:

CLOSED BY ORDER OF THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT

The Secretary of Energy Has Determined That This Unit

Represents An Unjustifiable Expenditure of Our Nation’s

Precious And Dwindling Energy Reserves. DOE 568-90-3041

Smith’s protagonist is Lieutenant Edward W. Bear, known as Win, a detective for the Denver police force. Like a thousand other gumshoes from hardboiled crime fiction, he’s middle-aged, world-weary, bitter and cynical from a long career dealing with the worst of humanity. Also from the handbook of genre cliches, he’s the sole honest man in a world of pervasive corruption, betrayal and violence.

He’s sitting in his car, trying to eat lunch, sick to his stomach from a brutal murder scene he witnessed that morning. Win narrates:

Most of all I longed to take off my sodden jacket, but the public’s supposed to panic at the sight of a shoulder holster. I knew that sweat was eating at the worn, nonregulation Smith & Wesson .41 Magnum jammed into my left armpit. The leather harness was soaked, the dingy elastic cross-strap slowly rasping through the heat rash on the back of my neck.

If it were only—hell, make that five years ago. A man could enjoy a sanitary lunch in an air-conditioned booth. Now, CLOSED BY ORDER signs flapped on half the doors downtown; the other half, it seemed, had been shut by “economic readjustment.” And unlicensed air conditioning was a stiffer rap than hoarding silver.

Like Atlas, TPB begins with the world already in a state of decay, but never circles back to explain how things got to that low point. Like Rand, Smith assumed his intended audience would take this for granted and wouldn’t demand a deeper explanation. Still, it’s fun to pull at the threads of a fictional world and see how it holds up.

Why is there an energy crisis in this world? What’s changed from five years earlier?

Obviously, Smith’s description of energy shortages echoes the real-world 1973 OPEC oil embargo, where Arab states refused to sell petroleum to Western allies of Israel, and then the 1979 oil crisis after the Iranian revolution.

To people who read this book when it came out, those would be recent memories. Americans from that era remember long lines at the pump, skyrocketing prices for gas, painful inflation, and government plans for rationing. However, Smith never says if his timeline went through the same crisis, or if something else happened instead.

Is there an actual energy shortage? Did Smith’s world hit peak oil early and then fail to develop any alternatives to fossil fuel (solar and wind energy don’t exist in this book), resulting in permanent depression because energy really is scarce? Or is there plenty of energy, but no one can get it because the government is hoarding or mismanaging it?

Are the repressive laws a heavy-handed response to a real crisis, or did the government concoct a crisis as an excuse to pass repressive laws? Which answer a libertarian goes for says a lot about their politics. Do they believe socialism is a well-intentioned attempt to help people that inevitably goes bad, or was it only ever an excuse to seize power and impose tyrannical rule?

Smith doesn’t say, but his explanation seems to hew closer to the latter. He believes that government never has done or can do any good for anyone, that it’s always power-hungry tyrants imposing rules on people against their will. In his worldview, “government = evil” is the only thing you need to know. It accounts for everything, so no deeper cause-and-effect explanation is necessary.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series: