The Probability Broach, chapter 9

Safe and sound (for the moment), Win Bear continues his research into why history unfolded so differently in this anarchist universe:

I hunched over the Telecom, a stranger in a strange land, trying to figure out how we both got so strange. What real differences were there between the Encyclopedia of North America and the smattering of history I could recall?

…What really differed was interpretations.

In 1789, the unlucky year 13 A.L., the Revolution was betrayed. Since 1776, people had been free of kings, free of governments, free to live their own lives. It sounded like a Propertarian’s paradise. Now things were going to be different again: America was headed back—so Lucy and the encyclopedia said—toward slavery.

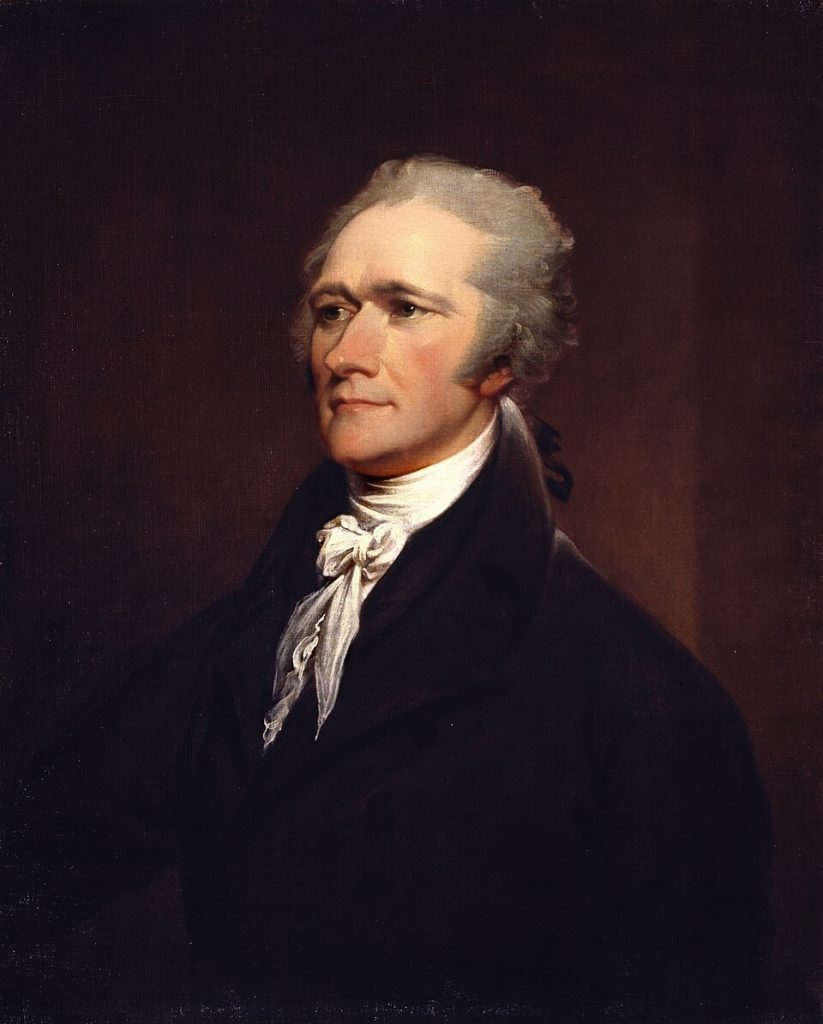

The fiend responsible for this counter-revolutionary nastiness was Alexander Hamilton, a name Confederates hold in about the same esteem as the word “spittoon.” He and his Federalists had shoved down the country’s throat their “Constitution,” a charter for a centralist superstate replacing the thirteen minigovernments that had been operating under the inefficient but tolerable Articles of Confederation.

Headed back toward slavery? That’s a cringeworthy turn of phrase, given that even in L. Neil Smith’s alternate timeline, America still had real, actual slavery at this point.

“People” most certainly weren’t “free to live their own lives” in that era… unless by “people”, he meant “white men”. As I’ve mentioned, this is a persistent blind spot of his.

We’ll discuss more about the North American Confederacy’s history later, but for now, here’s a quick reminder: In their world, as in ours, the Constitution superceded the Articles of Confederation. The divergence point is the Whiskey Rebellion against the nascent federal government.

In our world, it fizzled out. In the Confederate world, it succeeded. George Washington was executed, the Constitution was scrapped, and the United States government was overthrown, giving rise to an anarchist society.

To hear Smith tell it, centralized government is the source of all evil. Once the Constitution was abolished, America experienced an immediate renaissance – not just technologically, but morally.

A case in point is his treatment of slavery, as told by Win:

Confederate history after the Rebellion was a mishmash of the familiar and the fantastic. Gallatin adopted a new calendar and a system of weights and measures, both devised by Thomas Jefferson.

…Jefferson enjoyed an even more illustrious career than back at home. Fourth president, after Edmond Genêt, he’d almost single-handedly lectured, argued, and shamed the country into giving up slavery, freeing his own slaves in 31 A.L. On the lecture circuits, four years later, an irate reactionary put a nine-inch dagger into his leg, leaving Jefferson with a limp and a cane he carried the rest of his life. They hauled the assassin out with a faceful of pistol lead, as the inventive future president had mounted the rostrum bearing a repeating sidearm of his own design. He finished the speech before he’d see a doctor. Slavery was abolished in 44 A.L., the year Jefferson ascended to the presidency.

Hold on just a minute! I want to hear more about how Thomas Jefferson peacefully talked all slaveholders into freeing their slaves.

Smith doesn’t linger on this. He makes the claim, then hastily segues to a different image – a badass Jefferson blowing an assassin away – almost as if he’s trying to distract readers so we don’t ask for more details. (No surprise we don’t hear any of the actual words of these magically persuasive speeches.)

In our world, defeating slavery took the bloodiest conflict ever fought on American soil. Does Smith expect us to believe that all this death and devastation was unnecessary? Could Abraham Lincoln have prevented the Civil War if only he’d been a better speechwriter?

Smith drastically underestimates how simple it is to convince people to give up racist beliefs, especially racist beliefs they benefit from. He believes that once the right political system is in place, all prejudice will melt away and everyone will lose their desire to dominate others. Ironically, that’s very similar to what communists believe, only in service to more or less the opposite conclusion.

Of course, Smith has to say this, because he’s an anarchist. If people won’t freely make the right choice – for example, if they choose to enslave, oppress or discriminate against others based on race – the only other option is a state or state-like power to compel them. He can’t abide that, so his ideology requires him to believe that bad beliefs are easy to overcome. But his ideology patently clashes with reality.

All libertarians have to grapple with an inconvenient historical truth. The Anti-Federalists – the founders who were most in favor of limited government – didn’t hold this view out of devotion to an abstract concept of liberty. They held this view so that government didn’t interfere with their ability to own slaves.

For example, Patrick Henry – he of “give me liberty or give me death” – was an outspoken opponent of the Constitution. Why? Because he feared that it would give Congress the power to free the slaves:

“They will search that paper, and see if they have power of manumission. And have they not, sir? Have they not power to provide for the general defence and welfare? May they not think that these call for the abolition of slavery? May they not pronounce all slaves free, and will they not be warranted by that power? There is no ambiguous implication, or logical deduction. The paper speaks to the point. They have the power in clear unequivocal terms; and will clearly and certainly exercise it.”

(See also this paper, and this article arguing that the Second Amendment was ratified to protect the legitimacy of slave-patrol militias.)

The enslavers who opposed the Constitution were explicit about their reasoning: With a weak central government, they’d be able to do as they pleased. But a strong central government might one day come under pressure to liberate its enslaved citizens, and would be capable of doing so.

Meanwhile, although Smith loathes Alexander Hamilton for being the architect of strong central government, he did more than most founders to fight slavery.

Hamilton founded the New York Manumission Society, which called for (and achieved) the abolition of slavery in the state. During the American Revolution, he lobbied for enslaved people to be permitted to join the Continental Army in exchange for their freedom.

After the war, he argued that enslaved people who escaped to freedom on the British side shouldn’t be returned to slavery after Britain’s surrender: “as odious and immoral a thing as can be conceived… to bring back to servitude men once made free.” And after the Haitian Revolution, where a slave rebellion succeeded in overthrowing colonial rule and creating a free society – and terrifying the colonizing powers of the Western world – Hamilton was one of the few who advocated trade and diplomatic relations with the new Haitian government.

To be fair, Hamilton didn’t have completely clean hands. Despite his abolitionist advocacy, he married into the wealthy, slaveholding Schuyler family. He also swallowed the pro-slavery clauses of the Constitution to win Southern support for ratification.

Given how deeply slavery permeated the early American economy, none of the founders were free of its taint. However, it’s fair to say that Hamilton was more anti-slavery than most – both in his words and his deeds.

As for Thomas Jefferson, he talked a good game about ending slavery. He wanted to put anti-slavery language in the Declaration of Independence, though it was deleted at the insistence of slaveholding delegates. As president, he signed a law banning the international slave trade, which he called “violations of human rights which have been so long continued on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa”.

Nevertheless, when it came to the most obvious thing he could have done – freeing his own slaves, both for their sake and as an example to others – Jefferson failed. He didn’t even emancipate them in his will.

For all his rhetoric, he was acutely aware that the wealthy, plantation-owning class of which he was a member depended on the labor of enslaved people to support them and enable their aristocratic lifestyle. If slavery were abolished, that economic system built on exploitation would collapse. That was a sacrifice he wasn’t willing to make.

This fact doesn’t sit well with L. Neil Smith. So he rewrites history to conform to what he thinks “should” have happened.

He erases Alexander Hamilton’s anti-slavery advocacy so as to more easily villainize him. He recasts Jefferson the slaveholder as a principled hero of abolition. In doing so, he bulldozes the messy, inconvenient facts of real history, so he can put all the “good” people on his side and all the “bad” people on the other side.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series:

Smith, probably accidentally, has one point here. The earlier in US it was done the easier freeing slave would be. As southern industry became more dependent on slaves the southern people embraced more racist beliefs to justify their system. The more racist the people the more they could justify huge plantations built on slave labor, making them more dependent on slave labor. It was a bit of a cycle that strengthened itself over time. The stronger this cycle the harder freeing the slaves was, both because it crashed the southern economy and because much of the population was strongly racist.

I wonder, did Smith mention the war of 1812? Without a strong central government the US could easily have lost the war and become part of the British Empire again. The US victory was built on the US Navy keeping the stronger British Navy from entirely controlling and blockading the coast. Plus, with a weaker central government there would be the possibility of individual states cutting a deal to get favorable treatment from the British in exchange for switching sides.

Argh. I did not know that about Patrick Henry.

I didn’t know that (or much else) about Patrick Henry, but given the existence of Patrick Henry College (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Henry_College) I’m not surprised.

I had thought Thomas Paine was the only “Founding Father” opposed to slavery. Hamilton’s record seems a bit mixed, but perhaps I’ve done him an injustice.

In general, the Federalist founders were more vocal about opposing slavery. Those would be people like Hamilton, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin (although Franklin came around to that position later in life than most people realize).

Even among the Anti-Federalists, there were quite a few who recognized that slavery was morally wrong. I’d count Jefferson among that group. The difference is that most of them didn’t think there was anything the state could or should do about it. They just hoped that it would die out naturally in the future.

Sorry, Win, but once the events of the two histories go in different ways it is no longer about differing interpretations. This reads like a high school student who just found out that historical revisionism, in the sense that reputable academics use it, is mostly disputing motivations for acts and not the acts themselves, and then applies them to a case where it doesn’t apply because the facts are different. (It also reminds me of Ken Ham saying that creationists accept all the same facts that scientists do, and differ only in interpretation, which would be a lie even ignoring that all interpretations are not equally valid.)

I forgot who Lucy was at first. She’s the woman who was with Ed, right? It’s been a while since she was mentioned.

I really don’t want to do this. I really, really don’t want to do this, but nobody listens anyway. I will say it as simply and plainly as I can: L. Neil Smith is not an anarchist. You keep calling him one, but that is not true. Anarchism does not mean just “anti-state”. It means opposition to all hierarchy and authority, any system that oppresses people. That clearly includes capitalism. Do you really think that only states can be oppressively hierarchical? Because if so, you are repeating the errors of Smith. If not, you should understand why libertarians are not anarchists, and not continue to spread this misinformation. Whenever anyone else corrects an error you listen, but I’ve brought this up three or four times now and you ignore me.

Funnily enough, this very chapter shows this to be mistaken. Slavery is the worst hierarchy there is. It goes utterly against our principles. But take the federal government away and the slave owners continue to enforce slavery—they pretty much ARE the state governments. (In the story’s present there doesn’t seem to be state governments, but returning to the Articles of Confederation would have established that state governments as fully sovereign, so either Smith is confused or they must have been abolished later. Or both.) Opposing hierarchy means slavery cannot be tolerated, so an anarchist would support a slave rebellion, slaves liberating themselves, while Smith would not because of the planters’ property rights. Instead he has to invent the ludicrous idea of the slavers being convinced to set them free voluntarily with no compensation, which makes about as much sense as a communist vanguard party voting to abolish the state after using it to consolidate power. All this to say that, if propertarians like Smith believe that putting the right system in place will automatically make people do the right thing, and anarchists hold the opposite, that people must be convinced of the right thing before the system can be changed (this is called prefiguration) then Smith and anarchists believe in opposite things. Therefore, they are not the same.

Lucy is Ed’s elderly neighbor who’s helping out around the house while Win recovers (see this post, for one mention). She’ll be more important later.

This sounds like No True Scotsmanning to me. There are left-wing and right-wing forms of anarchism; this book is the latter. Anarchist thinking isn’t anti-capitalism by definition, just some varieties of it.

Funnily enough, L. Neil Smith would agree with you that oppressive hierarchies are bad. He’d just say that the way to prevent them from arising is through free markets, which let people buy and sell to each other without coercion or hierarchy. (He actually depicts this in the book; most businesses in the North American Confederacy are small partnerships run out of the owners’ homes.)

For what it’s worth, I agree with you that this is absurd. But I don’t think that makes him not an anarchist. I just think he’s wrong about the way his ideas would play out in the real world.

Though I disagree with you on this point, and many sources agree with me, I will stop harping on it now that you have explained your reasoning. I just thought you were ignoring my argument altogether; I’m glad this is not the case. But since we disagree on definitions, there is no point in still arguing.

Now I can finally get back to enjoying you tear this book a new one.

A lot of people seemed to have believed that slavery would die out on its own, with strong disagreements about what conditions would speed or slow that dying out. While some folks were probably sincere, others were probably using that idea as a dodge to avoid taking earlier action (and on the pro-slavery side, I’m sure some people took “slavery will die out on its own” as code for “we can’t politically afford to ban slavery know, but will someday). By the standards of white Americans of the time, Hamilton was quite antislavery – but he allied with Washington who was very comfortable with slave-owning, selling and catching. But Smith makes the interesting choice of painting Hamilton and (as you will later see, Franklin) as villains, while balancing his use of Washington as a villain with praise for Jefferson, Henry and others. Jefferson gets “pro-freedom in abstract sense in spite of owning slaves” treatment, while Hamilton (and Lincoln) must have bad motives for actually supporting freedom for actual people.

Smith seems to have called himself an anarchist, and believed he was an anarchist, and wrote his vision of what he thought “anarchy” would look like. So that’s enough reason to call Smith an “anarchist,” if an amazingly stupid, deluded, dishonest and unhinged one.

It’s sort of like how we really couldn’t stop Stalinists, Maoists, Hoists, Castroists, etc. from calling themselves “Communists,” even though none of them really ever had a system that fit the proper definition of that word either.

Defeating slavery in the United States required bloody war. Elsewhere… not so much.

Yeah, in what would eventually become Canada things were a bit complicated, but it was generally done just by changing the laws and while there were occasional riots there were no major wars. Upper Canada banned the importation of new slaves in 1793, freed escapees and children once they came of age, but didn’t free existing slaves owned by locals; importation of new slaves into most British colonies was ended in 1805; the slave trade was abolished in 1807 by both England and the U.S., and England used that to pressure other countries into complying as well; and slavery was essentially abolished throughout the British Empire in 1833-1834. (There were a few complications and holdouts; apparently Nigeria still had slaves until 1937.)

By the 1860s the U.S. was already almost alone as a major nation for slavery being still such an active thing.

@ jenorafeuer: the reason most USAians don’t know much about slavery is down to the absolutely wretched way history is taught in most schools. It usually goes: Plymouth Rock, pilgrims wanted religious freedom, War of Independence, Lincoln freed the slaves (only mention of the slaves), WWI, WWII and maybe Korea but probably not.

Anecdota that started me thinking about the way the USA teaches history in high school: At one family gathering, for some reason the topic turned to American history, and my kids revealed they never went past WWII in any history class they had in high school–no Korea, no Viet Nam, no Civil Rights or moon landing or anything that came after that. I realized that I had never gone past WWII in any history class I had in high school. Then my father revealed that he’d never gone beyond WWII…and I pointed out that he’d graduated high school in 1955 so the Korean war hadn’t been over very long and the textbook writers figured nobody needed to learn about it because they were alive for it. But we all three had American History classes in three different states–in my case, first overseas in a DoD school and then stateside in a civilian school.

TL;dr: History is taught very poorly in the USA.

My Florida school had a state-mandated course on “Americanism vs. Communism” so we got a lot of Cold War stuff. Probably not accurate stuff — I honestly don’t remember much of it though.

I think I’ve mentioned this in comments here before, but one of the things that people often fail to realize is that banning the part of the ‘Triangle Trade’ that involved bringing slaves across the Atlantic to the U.S. was actually done with the active support of the rich and politically-connected Southern plantation owners.

Because if there weren’t new cheap slaves being brought over from Africa, that made their ‘breeding stock’ more valuable. So, yes, the biggest slave owners were actually all in favour of banning the Atlantic slave trade; at least, once they had enough slaves themselves to run their plantations, and could now make extra money by selling slaves to others. Banning the trade didn’t make things any better for the people who had already been enslaved. It didn’t even entirely stop the trade, obviously; it just meant it was now solely the realm of smugglers rather than ‘legitimate’ operators.

And then when Napoleon tried to re-take Haiti and re-institute slavery there, Britain had a surge of abolitionist support (screwing over the French was a big plus in their books), cracked down on that smuggling, and helped kick off the War of 1812 because they were obviously checking out American ships for this. (On top of the usual excuse of looking for escaped British sailors.)

@5 jenorafeuer: It’s also important to note that while the slave trade was abolished on paper it was never strongly enforced. In many cases ships were made in the US for the slave trade and then on paper operated from Africa to Cuba, Brazil or other ports were it was still legal. When in reality most or all of the slaves went straight to the US.

At no point did the southern states breed enough slaves to maintain the population. One of the reasons some northerners supported banning the slave trade was the belief that it would fade away without constant imports. Most southerners also opposed the ban for the same reason.

Hold on just a minute! I want to hear more about how Thomas Jefferson peacefully talked all slaveholders into freeing their slaves.

“The Magic of the Marketplace,” I guess. Or some kind of magic. The same magic that, according to libertarians, will cause all individuals and businesses to Take Responsibility and always do the right and rational thing forever, starting as soon as government disappears.

In our world, defeating slavery took the bloodiest conflict ever fought on American soil. Does Smith expect us to believe that all this death and devastation was unnecessary?

I dunno about Smith, but Southern apologists insist that the US Government could simply have bought all the slaves peacefully and then emancipated them; and Tyrant Lincoln was a Nazi for using force to free them instead.

I spose its predictable that this be insular but there’s a whole world outside of the geographic chunk of North America that was the new nations – real and aternate timeline – and the reactions of other global powers at the time to events in what had been the Colonies and were now a newly declared..

countryanarchy would be intresting.At the same time that all this was happening https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1789 * and developing from there none of the colonial empires – the British, French*, Spanish, etc. meddles or interfered? Tried to stop, take over or aid the new Confederacy?

Pretty sure some European colonial empires mostlikely the Brits would’ve tried to take oevr the new anarchies land so .. hhmm.. Yeah. Would be nice to have seen L. Neil Smith.address that at some point.

.* 1789 was the start of the French revolution so oaky, probly NOT them -or maybe them more than others? Distracted but also coming up with a very new model of govt incl new calendar etc..would they have seem them as allies? Rivals? .

Libertarian “thinking” has always been as insular as it gets. They’re still stuck in the old standard US-exceptionalist worldview of “America is protected from the rest of the world by two oceans so the rest of the world doesn’t matter.” And, being CONSISTENT and all, they never learn jaque merde about anywhere else. If you think libertarians are stoopid when they talk about America, just wait till you hear them talk about other countries.

Smith does mention that, after the U.S. becomes an anarcho-capitalist society, those political principles eventually spread throughout the world and inspire revolts against government everywhere. There’ll be some mention of that later in this chapter of the book.

@Katydid, after me@4:

Made me think. I never got past the Industrial Revolution. In fairness, there was a LOT more history to teach, what with me being in the UK.

@9: I’m beginning to thing the lack of teaching on current history was on purpose, don’t you?

Along with Katydid and sonofrojblake, I found that our history education in secondary school was abysmal.

In my case our Advanced Placement American History course was taught by an American Civil War scholar. So we spent six weeks getting to 1860, four months on the American Civil War, and if there was any time left over we tried to reach the present day. I think we got to the start of WWII.

For many years I have thought that we should teach history backwards. That is, here we are today, let us work backwards as a class and see the events which brought us here. That strategy may miss things like the Magna Carta, or the religious zealots landing at Plymouth Rock to enforce the practice of a single version of a religion, but it might be more interesting. Class projects might include tackling the history of a single current issue, and the students presenting their findings to the class.

@ flex, I had the same AP US History experience you did, with the exception that my teacher was not any particular source of excellence, just a long-term sub. For us, the interminable period was the War of Independence–and we never heard about the war of 1812. A few years after I finished college (without ever having to take a college history class because I somehow scored high enough on the AP test), the Billy Joel song We Didn’t Start the Fire came out and I was at a loss for all the references in the 1950s and 1960s except for Panmunjom–the signing of the agreement there in 1953 was a huge part of the ending of the hit tv show M*A*S*H. We never got to that point in any history class I had ever taken.

Also, I agree with the approach of “How did we get here? Let’s discuss…”

“He and his Federalists had shoved down the country’s throat their “Constitution,” Any reasonable amount of research would show the Constitution was hotly and intensely debated around the country. It wasn’t imposed by fiat. I realize that’s unimportant to Smith but it’s true.

“The First Emancipator” is an excellent book on Robert Carter, who had 300 slaves and wound up freeing them all — which the author points out shows that there was no excuse for Jefferson and Washington apologists to insist it couldn’t be done.

That sounds like a book I’d like to read! Thanks for the recommendation.

You’re welcome.

A friend of mine who did a history thesis on Carter is mentioned in the footnotes, though I didn’t know that when I read it.