The Probability Broach, chapter 8

Speaking as a policeman, Win Bear is still incredulous that the anarcho-capitalist North American Confederacy has no such thing as license plates or driver’s licenses. He’s disturbed that his counterpart, Ed, is nonchalant about it:

How could I explain that licenses are necessary to public safety, especially when his culture apparently found no use for such a concept? “Look here, Ed, how many people get killed on your roads every year?”

… “No idea at all.” He reached for the Telecom pad. “Last year, around five or six hundred if you discount probable suicides.”

“What? Out of what population—and how many of them drive?”

More button-pushing. “Half a billion in North America, and maybe three vehicles for every person on the continent.”

This passage is a nested onion of implausibilities. Let’s unpeel them one at a time.

First: How does Ed – or anyone – know how many people are killed by car accidents in the North American Confederacy?

There might be media coverage of some car crashes, especially spectacular ones, but there’s no reason to believe it would be comprehensive. There’s no census, no Social Security Administration, no government agency keeping track of people. There are no police whose duty it is to investigate fatal accidents. There’s no requirement to report a death, and no central registry to report it to.

So, again: Where does Ed get this number from? Shouldn’t the only possible anarchist answer to this question be “I have no idea”?

Second: How can it possibly be true that the NAC has fewer traffic fatalities than our reality (which suffers around 40,000 traffic deaths per year)? Smith never even tries to justify this. Just think of what doesn’t exist here, in a society with no laws about what you can drive or how.

There are no speed limits. Not just the highways, but every road is an Autobahn. You can floor the gas pedal and roar at top speed through quiet residential neighborhoods where kids are playing. You can do wheelies in front of a school or drag-race through crowded streets for fun. (Even Germany is contemplating speed limits for its famous Autobahn, to reduce pollution and prevent deadly crashes.)

Since there are no driver’s licenses, there are no restrictions on who can drive. You can get behind the wheel if you’re a little kid, or if you have impaired vision, or if you have seizures. You don’t have to pass any test to prove you know what you’re doing.

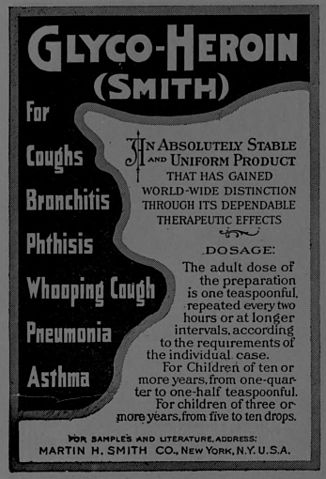

There are no drunk driving laws. You can get behind the wheel blackout drunk, or high as a kite, or stoned on whatever recreational substance you like.

There are no laws regulating the size or shape of cars. In fact, you can intentionally make them more dangerous. You can mount a bulldozer blade on the front to push other vehicles out of the way. You can put spikes on your bumpers to defend against other drivers, as I suggested previously. You can add rocket boosters to go faster, and too bad for anyone who’s behind you when you hit the afterburners.

Or, in a less fanciful example, you can drive cars so massive and heavy that anyone you hit is almost certain to die. In the U.S., pedestrian fatalities have been rising, and our national obsession with heavy trucks and giant SUVs is the reason why.

You don’t have to have crumple zones, airbags, anti-lock brakes, or any of the other safety features that governments have mandated from years of hard-won experience. You can own a car that turns its passengers into projectiles, or explodes in a violent fireball, if it collides with something. (After all, safety features cost money! Why not leave them out to get a cheaper price? I know I’m a good driver, so nothing bad will happen to me.)

You can drive any kind of weird or experimental vehicle you want, whether or not it’s been through safety testing. You can roll out computer-controlled driving with insufficient testing, and use your customers as crash test dummies.

In flavor text from a later chapter, Smith not only agrees with this, he doubles down on the idea that you can drive literally anything you like, including cars powered by dynamite or on-board nuclear reactors:

North Americans adore any contraption that moves under its own impetus; they’ve harnessed every conceivable form of energy (and not a few inconceivable ones) to propel that most fantastic of their inventions, the private ground-effect machine. Steam and internal combustion compete with electricity and flywheels; there are fables of “hoverbuggies” run by enormous rubber bands, caged animals, charges of dynamite; and now, nuclear fusion. Secretly playing Prussian Ace in a cloud of turbodust or reading quietly while computers guide them along the Greenway at 300 miles per hour, they don’t care much about the power source. Within the portable privacy of their road machines, they have tapped a greater source of energy, the inner contemplation of a powerfully creative people, which is the source of all their lesser miracles.

The obvious fallback for an anarcho-capitalist would be to say that there’s no government which makes laws, but the private companies that presumably own the roads do mandate safety features. However, if this is Smith’s solution, he never says so, and excerpts like the one above suggest the opposite.

People in the North American Confederacy appear unused to any rule that restricts their freedom to do as they wish. As you may remember from last week, Ed is unfamiliar with the concept of license plates – suggesting that no private entity requires anything like it either.

What this shows is how L. Neil Smith’s brand of anarchy implies a radical rejection of basic political theory.

In standard political thinking, people agree to come together and create society, giving up some rights in exchange for the protection and benefits that the state offers. You can conceptualize this as a spectrum. On one end is absolute liberty – freedom in its raw and primal sense, where there are no rules except the law of the jungle. On the other end is an all-powerful totalitarian state, which guarantees safety and order by controlling everyone’s lives.

Few people would go to either extreme. But most of us would agree that some rules and some kind of governance are necessary. We just differ about which point along this spectrum strikes the most desirable balance.

However, Smith denies this framework altogether. He seems to believe that there is no tradeoff between liberty and safety – that, by getting rid of all laws, we somehow become safer as well. It’s “you can eat your cake and have it, too” as a political philosophy.

If he made an argument for how or why this win-win scenario could arise, that would be one thing. But he doesn’t. His position doesn’t come from any reasoned argument or consideration of the evidence, but through pure magical thinking.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series: