The Probability Broach, chapter 6

Lying in his hospital bed as he recuperates, Win tries to figure out exactly when and where he is and what’s happened to him.

His initial belief was that he was somehow thrown forward in time. However, some questions for Clarissa, the doctor who treated him, quickly rules that out:

But according to my shapely physician, today was Thursday, July 9, 211 A.L. After reflecting, she added that A.L. stands for Anno Liberatis.

“That’s something, anyway. Mind if I asked what happened two hundred and eleven years ago?”

Clarissa shook her head in bewilderment. “But how can you not know? That’s when the thirteen North American colonies declared their independence from the Kingdom of Britain.”

Doing the math, Win works out that 211 years ago corresponds to 1776 in the timeline he’s used to (since this book is set in 1987). That disproves his time-travel hypothesis, since the year in this place is the same as where he came from, even if they use a different calendar.

However, Clarissa refers to this society as the North American Confederacy, which catches his attention:

“Hold it! Confederacy? Let me think—who won the Civil War?”

“Civil War?” she blinked—at least it was a change from headshaking. “You can’t mean this country, unless you count the Whiskey—”

“I mean the War Between the States—tariffs and slavery, Lee and Grant, Lincoln and Jefferson Davis? 1861 to 1865. Lincoln gets killed at the end—very sad.”

Clarissa looked very sad, systematic delusions written all over her face. “Win, I don’t know what you’re talking about. In the first place, slavery was abolished in 44 A.L., very peaceably, thanks to Thomas Jefferson… And in the second place, I didn’t recognize those names you rattled off. Except Jefferson Davis. He was President—no, it would have been the Old United States, back then—in, oh, I just can’t remember! He wasn’t very important.”

I’ll give L. Neil Smith this much credit: at least he acknowledges that slavery existed.

This is in contrast to Ayn Rand, who tried to erase slavery from American history because it was ideologically inconvenient. She treated history as a morality tale, like a capitalist version of Pilgrim’s Progress, culminating with America, the freest and therefore best nation that ever existed. Slavery doesn’t fit with that story, so she ignored it.

Smith can’t be faulted for that. However, the way he deals with the problem is only a little better. The idea of peacefully abolishing slavery without a civil war is certainly appealing. But the idea of Thomas Jefferson being the one to do it has some massive and glaring implausibilities, which we’ll discuss later.

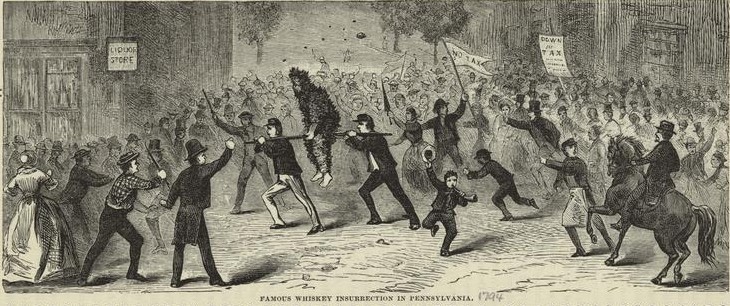

Clarissa mentions the Whiskey Rebellion, which plays a crucial role in Smith’s alternate history. Here’s how the book introduces the topic:

“Wait a minute, Clarissa, I didn’t catch that last bit.”

She sighed, giving in to the headshaking impulse again. “I said, Albert Gallatin was also the man who killed George Washington.”

If you’re not familiar with the historical backstory, the Whiskey Rebellion was spurred by the first tax America imposed.

After the revolution, the United States was in debt. The states had borrowed huge sums of money to pay for the war, and the federal government agreed to assume that debt. Either way, the nation needed cash to pay back its bondholders. Congress passed a tax on distilled spirits to raise revenue.

This tax was enormously unpopular on the frontier, especially in western Pennsylvania, where whiskey was the lifeblood of the agricultural economy. Federal tax collectors were intimidated and threatened by hostile locals. Some were tarred and feathered, or held at gunpoint and forced to resign. One was besieged at home by an armed mob and only narrowly escaped.

After months of escalating hostilities, some of the more radical frontier dwellers began to talk openly about a second revolution. A ragtag army of several thousand rebels gathered outside Pittsburgh, threatening to attack and loot the city. Eventually, George Washington raised an army and marched into Pennsylvania, and the rebellion melted away without a fight. Only two men were charged and convicted, both of whom Washington pardoned.

In real history, Albert Gallatin was an American founder who tried to negotiate with the whiskey rebels and urged a peaceful resolution to the conflict. In Smith’s alternate history, he joined them instead, and led a rebellion that overthrew the federal government, scrapped the Constitution, and recreated the United States as a utopian anarchy.

(Side note: if the whiskey tax failed in Smith’s universe, what happened to the people who loaned America money to fight for independence? Were they out of luck? Should’ve known better than to pledge your fortunes in support of freedom, suckers!)

The interesting thing about this, although Smith doesn’t dwell on it, is that his political philosophy is fundamentally anti-American. He believes that the ratification of the Constitution was a grave error and that George Washington was a tyrant who deserved to be shot. (He reserves even greater scorn for Alexander Hamilton, as we’ll see.)

Unlike many libertarians and conservatives who wave the flag and proclaim that the U.S. is a glorious beacon of freedom, Smith takes the opposite stance. He believes that all governments everywhere are oppressive tyrannies, our own not excluded.

I’m tempted to wonder if this is part of the reason The Probability Broach never achieved the same popularity as more uncritically patriotic libertarian fictions, like Atlas. The likely readers of such books aren’t looking for a philosophical lecture; they’re only looking for a reason to feel good about themselves and to be told that they’re the superior ones.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series:

The early colonies suffered massive losses of indentured servants and free men (and women and children) from disease and malnutrition.

The south could not have prospered without the forced, unpaid labor of countless slaves who worked themselves to death in the killing heat and rampant diseases endemic to the area. There is no way the plantation holders would have peacefully given up their slaves

Also, how do hospitals, like the one Win finds himself in, work in an anti-government society? As we see in the news, small and rural hospitals are closing because the gov’t has pulled back funding. And what about all the gov’t-funded research leading to new knowledge and cures? In a selfish, me-me-me society like Smith imagines, I don’t see philanthropists making up the difference out of their own pockets.

Some of us remember back in the 1980s, when conservatives insisted they didn’t want any gov’t dollars paying for research into AIDS.

Nit: He’s not in a hospital. The doctor is treating him in the home of his in-universe doppelganger.

Jefferson.

Thomas Jefferson freed the slaves peaceably.

Mister “Slavery is a horrible thing, please believe me (why do people roll their eyes at me when I say that), oh I can’t possibly just free my slaves, I have creditors who would bankrupt me if I started ‘giving away’ my, um, assets, so I’m going to take the coward’s way out by willing my favourite slave to herself when I die while pointedly ignoring the fact that we had children together and those children with my blood got sold elsewhere into slavery to other people to pay my debts”, that Thomas Jefferson?

… Yeah, I roll to disbelieve.

In addition to what Katydid said above about cotton plantations simply being not economically feasible to run without slavery, at least until the Industrial Revolution started making it possible to make machinery for some of the tasks (a fact which other people were asking at the time; the Civil War being only 30 years after horse-drawn combine harvesters started being built in the U.S. was almost certainly not a coincidence), the bit about ‘giving away my assets’ was one of the other major roadblocks to ending slavery in the U.S. Who was going to compensate all these ‘fine, upstanding business owners’ </snark> for the money they had paid for the slaves that the government was taking away from them? The federal government sure didn’t have the money; the southern plantation owners had already bankrolled much of the Revolution.

In many ways, the Civil War gave the abolitionists the perfect excuse to just free the slaves and not have to care about compensating anybody. “We fought a war over this, you lost, these are the terms of your surrender.” That said, Lincoln was a smart man and realized that if the South were left to wallow in poverty afterward, resentment would build up and ruin everything, and so he set up a massive (and not particularly popular) Reconstruction project to get the South’s economy on a more even footing again to head that off. Then, of course, Booth assassinated Lincoln and the whole ‘we just want to see them suffer for what they did’ attitude kicked into overdrive, and the resentment Lincoln foresaw just kept building up and became the driving force in American politics.

(The only time the U.S. has ever managed to get a reconstruction project like that to work was in Japan after WWII, and that was mostly because there was one man on site with the authority to do it, nobody else involved to try to veto it like with Wilson’s Fourteen Points after WWI, and he had most of it done during the occupation before people back home fully realized what was going on and could start screaming about how we were being too nice to those people.)

The problem with reconstruction wasn’t that after Lincoln the “burn them to the ground” mentality took over, but that Johnson gave over the power to the people who started the civil war in the first place.

Too many people in the US have swallowed the lost cause mythology.

… the nation needed cash to pay back its bondholders.

Particularly one Robert Morris, probably the second-most financier of the Revoluiion after the king of France, and the primary sponsor of Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s career.

Congress passed a tax on distilled spirits to raise revenue.

At the urging of Hamilton, who lied his head off claiming the tax would be collected at taverns, not from whiskey producers (farmers). Whiskey was the only economically feasible way to transport corn crops across the Allegheny Mountains, so that was how they made all their money – and the easiest point for the Treasury Dept to collect the tax.

… the Whiskey Rebellion was spurred by the first tax America imposed.

Only if you don’t count tariffs as taxes, and don’t count taxes imposed by states (which jumped by a factor of three or four compared to pre-Revolutionary taxation – hence Shays’s Rebellion, which triggered the Constitutional Convention).

… George Washington raised an army and marched into Pennsylvania…

Washington called in militia from other states. He attempted to lead them in person, but having suffered a recent injury from falling off a horse, was unable to ride even in a carriage, and handed off command to Hamilton.

…if the whiskey tax failed in Smith’s universe, what happened to the people who loaned America money to fight for independence?

Morris would have been wiped out (which he was eventually, blowing his reimbursement on failed real estate speculation). Hamilton wanted a strong central government, and not just for Morris’s sake; some say he deliberately provoked the Whiskey Rebellion to facilitate that. I recommend William Hogeland’s The Whiskey Rebellion: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and the Frontier Rebels Who Challenged America’s Newfound Sovereignty for detailing that case.

The leading supporter of the Revolution, King Louis XVI, was wiped out, six years after the Revolution officially ended – which probably would not have happened, at least not so soon, had the US fully repaid its debt.

Does Smith say anything about the Articles of Confederation? That minimalist government structure sounds much more to his taste.

This seems like an alternate-history wank, as alternate-history fans sometimes say.

This alternate history gets right that a successful Whisky Rebellion would lead to a weaker Federal Government than in OTL (our timeline). That would have a variety of consequences. No Louisiana Purchase? Britain, Russia, and Mexico being much less impeded in their claiming of territory in western North America? The US splitting up? A possibility is three nations: New England, the Mid-Atlantic and Upper South states, and the Deep South.

Such a US would not be anything close to a superpower, let alone a libertarian utopia.

…Such a US would not be anything close to a superpower, let alone a libertarian utopia.

I’ve never met a libertarian with even half that depth of understanding of history. They never seem to get beyond “America is the apex of human advancement, just think of how much more perfecter we’d be if only we got rid of government!” Their view of history (to the extent that they see it at all) is an absolute joke.

No kidding.

I grew up in Victoria, B.C., and visited the Royal British Columbia Museum many times (dating back to when it was still called the British Columbia Provincial Museum). One of the historical sections that has been there for as long as I can remember is a partial reconstruction of a ship that you can tour through, with descriptions of the history.

One of the things that it makes clear is that, back during the early to mid-1800s, the Pacific Northwest area was the site of a four-way trade and colonization ‘cold war’ between the English, Americans, Russians, and Spanish. The British ended up winning much of the northern parts of it, though there are still a lot of islands in the Strait of Juan de Fuca with Spanish names, and of course the Russians eventually sold their share to the Americans.

But yeah, with a weakened central U.S. government, the Oregon Boundary Dispute (54°40 or fight!) would have gone a lot differently and most of Washington State, anything north of the Columbia River, would have stayed British. The maximal British claim went down to 42° instead of the 49° that was the eventual end result of the treaty in our timeline… and at that point Mexico still claimed everything up to that latitude under the Adams-Onis Treaty. The United States could have been shut out of everything West of the Rockies.

Also, I’m betting that Smith didn’t have much about the War of 1812 in his alternate history… I find most Americans don’t think of any of that aside from the immortalized-in-song Battle of New Orleans in 1814, largely because the rest of the war was just such an embarrassment. (The U.S. tried to take over large parts of what is now Canada, but most of their planning seemed to assume that the general citizenry would be on their side against the British soldiers. When that turned out not to be true, things did not go well.) The only reason the U.S. didn’t actually lose territory then was because the British were more worried about Napoleon at the time and were willing to just go back to the way things were to end it all quickly. Though, granted, the fact that it was such a screw-up means it probably wouldn’t have been changed very much as a result of a weaker central U.S. government.

There was no War of 1812 in Smith’s timeline. The book doesn’t explain why, other than to say it was avoided.

There’s an index at the end with a timeline of his alternate history that takes a stab at an answer: “private navies” are just better (somehow) than state-controlled navies, so anarchist America sends out fleets of privateers that sink hundreds of British warships, easily defeating their attempt at a blockade and ending impressment before it ever becomes a problem.

Okay, I’m impressed that he actually mentioned it. As I said, most Americans don’t pay much attention to it, despite the fact that the American National Anthem was actually based on a battle in the War of 1812, not the American Revolution.

I will grant that if slavery was abolished in the U.S. prior to that point, the War of 1812 might not have happened as such. My line of reasoning is as follows, based on ‘our’ timeline:

– Several years before then, a treaty was signed banning the trans-Atlantic slave trade. (The big U.S. slaveholders were actually all for this, because it made their ‘breeding stock’ more valuable if nobody was going to be importing new slaves directly.)

– This didn’t actually stop the slave trade, of course, it just meant that it was now legally considered smuggling.

– Napoleon’s re-institution of slavery gave England’s abolitionists a lot more political clout.

– While England had already been harassing American shipping to check for escaped English press-ganged sailors, now searching for anybody carrying ‘contraband’ (i.e., slaves) became more of a thing, and the Americans couldn’t legitimately complain because they’d signed the treaty. (Yes, the hypocrisy of not considering the English sailors practically slaves is palpable.)

– The increased harassment of American shipping, and in some cases full impounding of American ships for smuggling, was one of the contributing factors to the War of 1812, as the Americans could point to the harassment and claim the British started it.

So if the U.S. had already abolished slavery completely (England abolished it in 1807, Jefferson was president until 1809, so both before 1812) the British might not have applied some of the pressure that led the U.S. to start the war.

From what you’ve said, though, it sounds like he went with a purely ‘government==bad, therefore government-led armies==bad’ approach. Which, I suppose, good on him for sticking to his thesis, but there’s a lot of history of mercenary units back centuries before that which throws cold water on that idea.

There’s an old joke about the War of 1812 that I think was from Pierre Berton: “Ask a Canadian about the War of 1812 and they’ll say ‘The Americans invaded, but we fought them back.’ Ask an American about the War of 1812 and they’ll say ‘The British tried to take away our freedom, but we fought them back.’ Ask a Brit about the War of 1812 and they’ll say ‘What war?'”

You’re assuming that Americans actually learned any history. The way it’s taught in the USA is absolutely atrocious. I say this as a USA-ian. We get the American Revolution, the Civil War (unless you’re in the South), and snippets of WWI and WWII…and that’s pretty much it. The Korean War, the Cold War, and Vietnam on forward are almost never covered–I didn’t get any of that and my kids didn’t get it either.

And some school districts don’t even cover what they do discuss very well, as illustrated by Sarah Palin–who, even immediately after going through a Massachusetts museum dedicated to the American Revolution and Paul Revere, was under the impression that Paul Revere rode to warn the British soldiers to look out for the unruly colonists.

I got what I and my parents considered a pretty decent liberal-progressive US-history education; but even then things like the Holocaust, the KKK and re-enslavement of Black Americans, fascist sympathizers in the US, and corporate-led anti-Communist, anti-socialist and anti-progressive propaganda, didn’t get discussed in that much depth. For example, we read, in a post-Civil-War chapter titled “Paths Not Taken,” that Lee was a proper Southern Gentleman and it was a Really Good Thing that he surrendered politely (which he did do), when he could have had his soldiers go underground and fight a long-running guerilla campaign against the Union (which in fact other Southern officers, soldiers and others DID do, that’s what the KKK was). They also didn’t explicitly say “The South waged a Civil War to keep their slaves,” even though they admitted in previous chapters that Southern politicians had been threatening bloodshed and civil war in direct response to the growing Abolitionist movement.

So, yeah, we’ve made some good progress in teaching decent history, but not nearly enough, and now Republicans are actively rolling back what progress we have made.

One likely consequence would be Britain finding the 1812 war much easier to win and deciding to reoccupy the thirteen colonies.

When I first read the book, I had no idea who Tadeusz Kościuszko was. He’s not mentioned in the book that I recall, but he’s an important part of early US history — and he connects to Jefferson and slavery.

(He reserves even greater scorn for Alexander Hamilton, as we’ll see.)

Such pathological hatred of Hamilton by the “limited government” crowd is about as old as Hamilton himself, and about as deranged as much of today’s “limited government” fanatics. And one major reason for this is that Hamilton’s idea of a strong Federal government has been proven right, many times, practically since he died if not earlier. Hamilton was a New Deal liberal WAAAY before it was cool, and we all know how much libertarians hate the New Deal.

Follow-on: There’s a line toward the end of the “Hamilton” musical where Thomas Jefferson says “Hamilton built us a financial system so strong I couldn’t destroy it if I tried. And I did try.

It’s interesting that Smith has the American Revolution followed by a second Revolution overthrowing (some of) the leaders of the first. In the real world, that kind of thing is associated with the Russian Revolution (Lenin over Kerensky), the French Revolution, and banana republics.

It’s been a long time, but I think Smith finagled things so the Louisiana Purchase still happened

In the Smith-verse, it wouldn’t have had to happen. Either the French Revolutionaries would have given up their North American territory in anti-imperialist fervor; or the French settlers in Louisiana (and their slaves) would have read the Articles of Confederation and spontaneously said “Yay, liberty, we wanna be Americans!”

@ Owlmirror: you’re right–I re-read. Win is in a hospital bed, but not a hospital. That was an assumption I made.

But that brings up another point: The other Edwin Bear is self-employed–with all the financial ups-and-downs that implies and he himself muses about–yet he has a huge house equipped with a hospital bed and advanced lifesaving medical equipment. I just had to go buy antibiotic cream and bandages from the local drug store and they are not cheap. Lifesaving medical devices with advanced capabilities would be ever-so-much more expensive. Also, how is electricity to run the devices sent to his home, and how does he pay for that? As I recall from history classes, the federal government had to force utility companies to electrify rural America because it simply wasn’t cost-effective for privately-owned utilities to run power out there.

This book reads like the fantasy of an elementary-school-aged child, where the technical aspects are just hand-waved away. Or, as lpetrich@4 says, an alternate-history wank.

If the timeline differs all the way back to the Whiskey Rebellion and probably earlier, then it’s kind of astounding that any recognizable individuals (such as, say, alt Win Bear) even exist after a couple centuries. It would practically require some force of destiny to make sure the right sperm always meets the right egg at the right time for multiple generations. Well, if there were an infinite number of alternate timelines, then maybe someone could somehow make a reality-piercing broach which can search out for the “nearest” timelines which happen to have a lot of the same people, but that seems an awful tall order for a prototype device made with 20th century technology.

Yes, yes, I know, it’s a Magical Plot Device™ and not Hard Sci-Fi, thus I’m being super nitpicky. Still feels weird.

The book discusses the implausibility of this! An upcoming post is going to be about that.

I’ve been dealing with that in a story I’m working on… though in my case the timeline-crossing device was created by somebody who was basically a classic ‘mad scientist’ and is literally half-magic, so ‘it works the way the creator expects it to work’ was pretty much baked into the concept. Still had a bit of discussion about it.

(The fact that my story has the SF hardness level of various iterations of Kamen Rider also helps. I wasn’t trying to be accurate.)

In the appendix we also learn that Lincoln killed John Wilkes Booth. How droll.

LOLWUT?! Did Booth get elected to Congress and get assassinated by wannabee-commie-tyrant-terrorist Lincoln?

Re: Magical Plot Device™: Star Trek is the most ubiquitous pop-cultural example of this sort of narrative, with its mirror universe where everyone’s a psycho and Spock has a goatee beard. It seems there’s not a single point of diversion between that universe and this – there are (per the execrable “Discovery”) actual detectable genetic differences between humans from there and humans from here, other than them all being psychos. And yet… we’re asked to accept that practically every person “here” has a physically near-indistinguishable equivalent “there”, starting at least at the timeline of “Enterprise”‘s fourth season (2154 in our calendar) and going up to near the end of “Deep Space Nine” at least (2375). So in a period of over 225 years, somehow precise physical duplicates of Jonathan Archer AND Nog, son of Rom, were somehow birthed, in addition to unlikely events like the changeling known as Odo somehow finding his way from the Gamma Quadrant to a specific space station half a galaxy away.

You must forgive this.

@Raging Bee: It’s a throwaway line (that I just looked up): Booth is on stage and is shot by “an obscure Hamiltonian lawyer” for unknown reasons.

So Smith-verse-Lincoln was “Hamiltonian” AND a lawyer? That means I’d guessed right: he was a wannabee-commie-tyrant-terrorist, and thus, by definition, so deranged that there’s no point in trying to find a reason for his tyrannical statist actions (except for maybe one of Booth’s lines was “sic semper tyrannis!” and that triggered the wannabee-commie-tyrant-terrorist?).

One reason Rand is more popular might be that there’s no L. Neil Smith Foundation giving away tons of copies of his books.

I can cut him some slack for his counterpart turning up — it makes no sense but I’ll swallow it for dramatic purposes. Sometimes I class “parallel world” as separate from “alternate history” — i.e., there’s no divergence, the other timeline is Just That Way.

By the same token I can swallow “what if Thomas Jefferson opposed slavery?” more easily than “if Thomas Jefferson opposed slavery, he could have ended it!” Um, no.