It has become a sort of pop-psychology truism that people who engage in prejudicial behaviour are doing so from a place of insecurity. It makes intuitive sense that if you don’t feel good about yourself, you can bring yourself up by tearing others down. Indeed, there is some evidence that threats to self-concept are likely to result in a preference bias toward the majority group (even among minority group members).

In a study by Ashton-James and Tracy, the authors propose a new hypothesis. They refer to the psychological literature that suggests that pride has two basic forms: hubristic and authentic. Hubristic pride refers to the kind of pride that is directed at one’s innate self-worth and deservedness – a kind of self-congratulatory, self-centred pride that is associated with narcissism and defensive self-esteem. Authentic pride, on the other hand, refers to pride taken in one’s accomplishments based on hard work rather than, for lack of a better term, special snowflakeness – it is associated with secure self-esteem.

The authors posit that hubristic pride will lead to increased prejudicial attitudes and behaviours, whereas authentic pride will lead to more compassionate attitudes and behaviours. They arrive at this hypothesis based on literature that suggests a relationship between self-esteem insecurity and prejudice. They go on to suggest that empathic concern is the mechanism by which this relationship manifests itself, since people who are more secure in their self-esteem are more likely to be able to be outwardly focussed and respond to the needs of others.

In order to test this hypothesis, the authors conducted three experiments, as well as a pilot study.

The Pilot Study

The first question to answer is whether or not there is an association between prejudicial attitudes and hubristic vs. authentic pride. To test this, the authors had 2,200 undergraduate students fill out the Modern Racism Scale, and the trait version of the Authentic and Hubristic Pride Scale (AHPS). Correlation statistics were calculated, and hte authors found a statistically significant low-moderate association between hubristic pride and racist attitudes toward black people.

Of course we know that correlation and causation are related but not synonymous. It’s possible (indeed, plausible) that people who are predisposed to racist beliefs feel more proud of their own race as a result. An experimental observation was needed.

Experiment 1

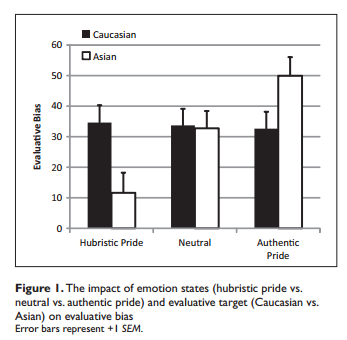

In the first experiment, 138 white students completed a task designed to moderate their levels of either hubristic or authentic pride. A ‘control’ group completed a task that did not moderate their levels. The level of modification was evaluated using the AHPS. Participants were then asked to judge the proportion of either the white or Asian population of Canada that was adequately described according to 4 traits (2 positive, 2 negative). Prejudice was defined as the difference between the means of the positive traits – people were not willing, in either group, to assign negative traits differentially between groups.

The results of the experiment suggest that, as hubristic pride is increased, so too is the likelihood to have preferential prejudices toward one’s own racial group (or against another group). Interestingly, while the control group reported roughly equivalent evaluations of both groups, people expressing higher levels of authentic pride responded more favourably to members of an outgroup, suggesting that authentic pride makes you more outwardly prosocial.

Experiment 2

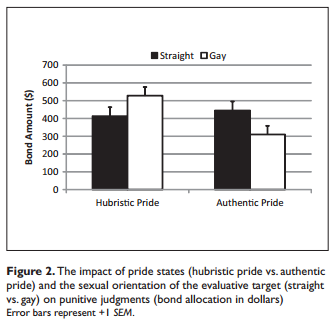

In the second experiment, 83 participants were again conditioned to exhibit either hubristic or authentic pride, and were then asked to assign a financial penalty to someone charged with committing a crime. The crime was identical except for the gender of the alleged criminal, making the crime either heterosexual or homosexual (the crime was sex in the men’s bathroom).

Again, we can see the difference between hubristically and authetically proud people – hubristic pride motivated a greater penalty to be waged against the gay defendant, while authentic pride lowered the penalty. The penalty was equal for both the straight defendants. What is interesting here is that the authors did not seem to measure the sexuality of the participants, or their levels of anti-gay antipathy. While randomization is done for the purpose of ensuring that these factors will be equal between the two groups, with a sample size this small, it may be a mistake to assume successful randomization for all relevant factors.

Experiment 3

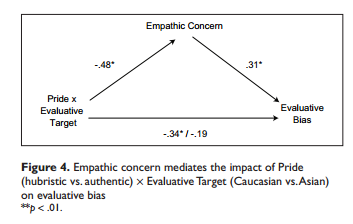

The third experiment attempted to demonstrate a plausible psychological mechanism for this effect. The authors suspected that authentic pride is associated with empathic concern for others. As mentioned above, as people’s self-esteem becomes more stable, they are able to become less self-centred, and become more aware of the needs of others.

In order to test this, the authors had 61 white students fill out a scale that measures empathic concern, as well as the same pride manipulating exercise from the previous experiments. When the results were analyzed, they found that the effect of pride on prejudice was moderated by empathic concern (i.e., the effect disappeared when you ‘control for’ the effect of empathic concern).

What these findings suggest is that it is not pride per se that affects the evaluation of in-groups vs. out-groups, but that authentic pride motivates someone to be more concerned for others, which then leads them to have more favourable views of out-groups than their own group.

Discussion

I would be remiss if I didn’t point out the weaknesses in this study, some of which I have presented as caveats below. First off, these are single experiments, with relative small numbers, performed on undergraduate students in the USA and Canada – we have to be conservative in the extent to which we can draw global conclusions.

Second, I am not at all confident about the use of Asian people as a stigmatized group in this context – not that Asian people are not stigmatized, but the reality is far more complicated (particularly in the context of a Canadian university that I assume to be UBC) than a simple ‘positive/negative’ axis. The authors do not seem to have measured whether or not there is a detectable stigma against Asian people in the study population, they simple assert its existence. This seems to be to be a critical flaw in their design.

Third, I am not confident about their description of the crime in the second experiment. They cannot, for example, determine that their target is stigmatized because he is gay, since they are manipulating sex, not sexuality, in the task. They simply assume that the study participants are evaluating a gay man, and do not check this assumption. Again, this seems like a potentially serious flaw.

Fourth, I am surprised that the authentic pride group expressed differential levels of outgroup preference while the control group did not (see Figure 1). I do not know why authentic pride would make someone prefer an out-group, rather than advocate for equality. It may be the case that the authentic pride group is a reflection of a positive bias toward Asian people that is counteracted by an equally negative bias in the control group (and overpowered in the hubristic group), but because no attempt was made to measure stigma about Asian people, it is not possible to know

Despite these flaws, this paper is attractive for a number of reasons. First, the description of authentic vs. hubristic pride made me laugh as I considered some of the people I run into in online debates about racism (or, to be honest, a lot of topics). Any supremacist group that believes it is intrinstically superior to another may be doing so out of psychological insecurity. It is not an accident, therefore, that these groups exhibit little compassion, or in some cases antipathy, toward outgroups.

Second, it prescribes a specific remedy for getting people to demonstrate externally pro-social attitudes: shore up their levels of authentic pride. Focus praise on what a group has accomplished, rather than its moral or intellectual superiority. By boosting authentic pride (hopefully at the expense of hubristic pride), we can potentially increase empathic concern. Any group that is looking to make its mission one that is focussed on serving others, and which wishes to combat prejudice, should pay attention to these findings.

I would like to see how hubristic pride correlates with cognitive burden, given what we already know about the association between cognitive ability and prejudice. Are people under greater cognitive strain more likely to adopt hubristic pride as a method of low-effort mental processing? Does hubristic pride fall along the same lines as system justification? Is there an association between cognitive burden and empathy – i.e., do you have to be mentally able to put yourself in the shoes of others?

Whatever the answers to these question, it may be the case that we can use these findings within the secular community. We know, for example, that misogynistic prejudice (and, to a somewhat lesser extent, racist prejudice) is a serious concern. I know that, to my admittedly biased eye, I recognized a lot of atheists in the description of behaviours typical of hubristic pride (arrogance, superiority, narcissism, defensive self-esteem), particularly among those who are strong opponents of making changes to combat inequality (although I am sure they’d make the same accusation about me). The question becomes whether or not we can use the knowledge of the difference between authentic and hubristic pride to promote more positive messaging within the community (e.g., “we are atheists because we grappled with difficult questions and developed good techniques” rather than “we are atheists because we’re smart and religious people are stupid”), and whether that would have a positive effect on our levels of prosocial interaction in other areas.

What this finding also seems to suggest is that undermining the self-esteem of others is a counterproductive method of increasing their levels of empathy. Far be it from me to suggest that anyone has an obligation to safeguard the self-esteem of bigots, but if one is specifically engaged in trying to increase empathy, attacking the self-esteem of your opponents would seem to produce the opposite effect.

In any case, I enjoyed this study a lot, and it has given me quite a bit to think about.

Like this article? Follow me on Twitter!

My first instinct, and I could easily be just plain wrong, is that their findings might be extremely specific to the context of both who they’re asking, what positive stereotypes they were asking about, and that they were asking specifically about Asian people. Given the stereotypes that are so commonly given to Asian people, I wouldn’t be surprised if people primed for “authentic pride” (which doesn’t seem so authentic to me here, but I guess it’s just a placeholder term), I wonder if people might be simultaneously being primed to have a high opinion of those stereotypes – hard work, intellectual, etc.

I might be way off base, I didn’t put a great deal of thought this.

Interesting start, but, given the flaws noted I’d want to see this embedded in more research (which to be fair may already have been done in part).

Thank you so much for this! It really resonates with me. I’ve always thought we needed a better way to distinguish valid dignity/pride in one’s accomplishments vs. egotistical hubris. I’m especially grateful, though, for the conclusion, which somehow I was never able to arrive at on my own before. It seems so obvious now! It really helps to have this idea as a tool to use when wanting to connect with others and maybe help them see my point of view, vs the frustrating feeling of believing others “too stupid” to get it. I never liked having the latter opinion, but didn’t always see how to get around it. Now I know I have at least one more good way to approach a problem to hopefully find an appropriate, compassionate resolution rather than just bullying vs. walking away.

You mentioned that the choice of Asians seemed potentially problematic; has anyone attempted to do this study using other ethnic groups?

I don’t know. I’d imagine that’s a Google-able question though.

I think the reason they chose Asians and not other groups is because this happened at UBC, and Asian students are the largest minority group on campus (whereas black people at UBC, or in Vancouver more generally, are far rarer and thus less likely to be stigmatized). It would have been better if they had chosen Coast Saalish, or even “Aboriginal people” as their stigmatized group, since there’s a buttload of stigma about First Nations in Vancouver.

This reminds me of something recently tweeted by @YesYoureRacist: Some dude actually wrote, “My great-grandfather probably owned your great-grandfather,” as if this were a point of pride. Setting aside the guy’s innumeracy, it seems like a perfect example of hubristic pride that has nothing at all to do with the accomplishments of the actual individual.

Certainly an interesting study, but I’m not convinced by the two kinds of pride idea, it seems pretty much like the old idea of secure/insecure self-esteem. And I’m not convinced that “authentic pride” makes one compassionate.

I think the difference lies more in ranking vs. linking or self-esteem vs self-acceptance. If you basically think of the world as a hierarchy, and of yourself as having something to prove, there’s a big incentive to put others down. If you don’t accept a hierarchy, and don’t need to shine to accept yourself, there’s no need.

Speculation, of course. What it suggests is that not so much bolstering someone’s “authentic pride” will help empathy and acceptance of others, but acceptance of that person, adopting and encouraging a world-view that is non-hierarchal, and using an approach based on cooperation rather than dominance.

Shaming someone will nevertheless be destructive, as it’s a dominance strategy and will automatically push them toward the hierarchal mode in the exchange.

.

Specifically for atheists, I’m not too happy with “we are atheists because we’ve grappled with difficult questions”. (I mean, have we? And sounds pretty much like “we’re smart.”) Maybe something like:

We are atheists because we don’t much like the skewed world that results when your single source of the truth is an old book, and we’d like to build a better world for everyone by testing ideas and seeing what works.

.

I’d say no, as animals (e.g. dogs) are capable of empathy, without necessarily having a theory of mind. And we often talk ourselves out of empathy by our own (angry) interior monologue .

Did you read the studies supporting the idea, or does it just not happen to pass your personal sniff test? Because there is empirical support – the authors of this paper didn’t just invent the idea out of thin air.

Indeed. Like that. That’s what the authors didn’t do.

A) That doesn’t really connect with the context out of which my statement arose, and

B) That is not necessarily true of all atheists.

I read some though not all of the material, and didn’t find it too convincing. e.g. the relived emotion task used in all three experiments could also engender other emotional states, like happiness. If there was a check to use on both sides of the tests only people in equal states of happiness, I missed it.

Yes, I am speculating, but there have been studies done on self-acceptance.

.

B) that they’ve “grappled with difficult questions and developed good techniques” is equally “not necessarily true of all atheists”.

and A) exactly. You are proposing that making people proud is the way to improve their relationship.

I think proposing an inclusive and egalitarian future as a common goal (which has nothing to do with pride) might be more effective.

This is testable: telling someone they did well/badly in a test vs. putting subjects in an inclusive cooperative / non-inclusive hierarchal environment. My hypothesis would be that the second has greater influence on empathy than the first.

Time will tell.

This isn’t related to the construct you’re criticizing though. They don’t establish the existence of hubristic vs. authentic pride in this study – they have taken it from the literature, where it has been tested in a variety of ways.

Sorry, I wasn’t clear.

I’m not doubting that there is a distinction to be made between the two kinds of pride, as between low and high, or should we say, false and real self-esteem. I’m just not convinced that authentic pride is the source of empathy, or of compassionate behaviour.

I’m not trying to disprove authentic pride can foster compassionate behaviour, I’m just proposing an alternative.

.

What I do take away from the study, is that the correlation is not between “pride” and compassion (which would generally be thought negative), but depends on the “kind” of pride.

Aha. I catch you now. No, I don’t think they were implying it as the source, merely saying that there is a relationship between them, such that hubristic pride is causally linked to discrimination by way of reducing empathic concern.

I think that is a good encapsulation of their thesis.

Then wouldn’t you expect a similar correlation for other pairs of emotional states like: angry vs. relaxed, frustrated vs. joyful, helpless vs. empowered? I would, which is one reason I think influencing world-view (e.g. ranking vs. linking, dominance vs. cooperation) rather than current emotional state offers better prospects of fostering compassion in the long-term.

Except that hubristic pride and authentic pride aren’t polar opposites like the ones you’ve listed here. They are two aspects of a construct that previously had been treated as a single emotion.

And the question isn’t “what is the best way to foster compassion?” Or, at least, that’s not my question or the question posed in this paper. The question is “what is the relationship between self-esteem and prejudice, and how can we better frame our messaging to achieve a specific goal?”

… people who are more secure in their self-esteem are more likely to be able to be outwardly focussed and respond to the needs of others.

No introverts have secure self-esteem?