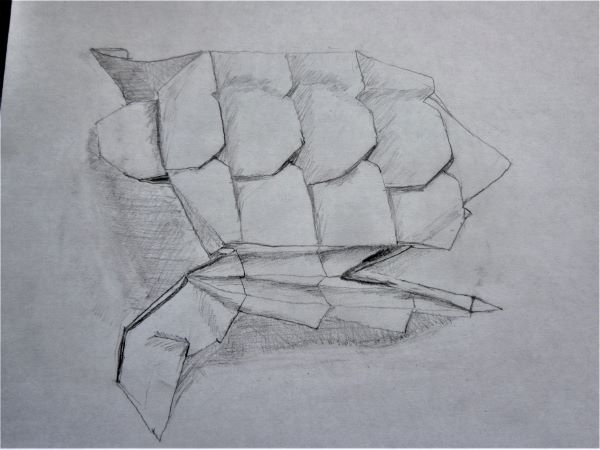

Origami Turtle, a pencil sketch by me, of an origami model folded by me. Someone at an origami meetup taught me how to make this. I do not know who designed it, possibly he did. ETA: I have identified the model as Baby Sea Turtle by Neige A.

Since I’ve been writing about AI art, I want to talk about the implications on my own artistic medium of choice: origami. Since I do not draw (although I have the ability to make a sketch), I’m not directly impacted by AI. But there are some distinctive artistic values that emerge from origami, and I think it might help explain where I’m coming from.

Origami as a participatory art

Origami is a form of sculpture that anyone can do. You can get a piece of paper and just fold it. You don’t even need to buy books to learn these days, you can just watch instructional videos for free. So far, this is not different from drawing.

However, teaching and learning is a far more central component of origami. Most people don’t buy origami models. While you could buy a coffee table book with just photos of origami, that generally isn’t what we imagine when we talk about origami books. Instead, we buy instructions to make our own origami.

The fullest way to appreciate and consume origami is to create our own art. The joy lies in the process of creation. And I know I show off a lot of complicated origami on this blog that readers will not be able to create themselves, but even if you’re not literally creating it, the creation process is still front and center. Much of the aesthetic derives from imagining what it’s like to make origami, or being inspired to try it.

The effort of folding

One of the contentions about AI art is that it makes it too easy, and that true art requires effort on the part of a human artist. Origami has some interesting things to say about that.

On the one hand, because origami is so focused on the creation process, a lot of value is placed on the high degree of effort involved. When we look at, say, Eric Joisel’s Commedia del’Arte, the complexity and detail is juxtaposed with the knowledge that it’s just paper. “How is this possible?” the viewer asks.

On the other hand, because origami is so focused on participation in the creation process, a lot of value is also placed on simplicity and accessibility. Ultimately, I don’t want you to feel like all origami is impossible, I want you to feel like you could do it. If I had a magic wand that could make origami easy for you, I would use it, and it would be great.

What if a tool made origami so easy that it deprived the folder of the satisfaction? That’s hard to imagine. One way a tool might make origami less satisfying is if it takes over the creative parts, designing the entire model from scratch. But the vast majority of the time, people are already folding models that they didn’t personally design, and they seem to like doing it.

But supposing there really was a tool that made origami so easy that it was boring, we could just not use the tool. Origami already forgoes the use of certain tools that could make things easier, such as scissors and glue. But even these aren’t hard rules. I have used glue to reinforce models where it felt necessary, and glue occasionally appears in classroom settings as well.

My external observation of drawing is that while artists speak of the importance of human effort, this value is not widely shared by viewers of the art. For many people, participation in drawing is so unimaginable, that they’re just not thinking about the creative act at all. I think what would help correct this, is if drawing were made more accessible, and people felt encouraged to give it a try.

Copies everywhere

Every time you participate in origami by following a set of folding instructions, you produce a copy of the original artwork. Copying other people’s work is by far the most common way to engage with origami.

There are ways to “steal” origami, but folding a model simply isn’t one of them. One way is to reproduce someone else’s diagrams without permission–though drawing your own diagrams is okay. That’s one reason I often don’t share instructions—you really just have to buy the books, or watch the videos! Another way to steal is by passing off someone else’s design as your own. If you’re serious about origami, you should always try to credit the designer.

However, origami is quite frequently taught in casual settings where folders—especially beginners—simply aren’t thinking about who the designer is, and may never know. There are also traditional designs of unknown origin. There are designs that are simple enough that they could plausibly have been independently designed by multiple people. There are designs that are derivative from other designs without being straight copies. Designs get reverse-engineered all the time, and it may be unknown whether these designs are copies. Origami designs are not themselves copyrightable, it’s just a matter of etiquette to give credit where we can.

Making money from origami

The participatory nature of origami naturally means that most people who make origami cannot be professionals. Most people are casual participants, or hobbyists like myself.

I don’t know very much about how people become professional origamists. Some may sell origami as fine art, or teach, or take commissions. According to Robert Lang, every professional origamist has their own unique skills and specializations. I get the sense that the most important skill is one that I don’t have, and don’t care to develop: sales. That’s probably true in drawing too.

I like that most origamists are hobbyists. I think it creates a friendlier environment where artists don’t feel they need to make money to achieve success (although there is still a lot of showboating). To make money, you have to produce something that’s scarce, either by doing something that most people can’t do, or are unwilling to do. But making art is not the same as making money, therefore art does not require producing something that’s scarce. Scarcity is at best a necessary evil.

AI in origami

There’s a great article titled “Origami AI — a roadmap” by Michał Kosmulski. I agree with him that for the time being, we aren’t going to get any AI-designed origami, because the techniques are just too specialized, and there’s a lack of training data. Perhaps more importantly, the economics just aren’t there.

Kosmulski also speculates that if AI could design origami, it would probably be less controversial than it is in other artforms. This is partly because most origamists don’t make money from the practice. But there’s also a lot of precedent, because there are many tools already available that haven’t really incited much controversy. For example, TreeMaker can make crease patterns to fold an origami base according to user specifications. I don’t have experience with TreeMaker, but I have used Reference Finder, a simpler computational tool. It’s just something you can choose to use or not.

On the other hand, Kosmulski points out that because origami AI would likely be based on smaller data sets, issues of AI plagiarism would be more worrisome.

Overall, I’m not that worried about AI in origami art. Nor in drawing for that matter, but I don’t draw so maybe my opinion doesn’t hold weight. My purpose in this essay has been to describe an artistic tradition that values accessibility and participation, and show why I think accessible art forms are great.

I’ve only done origami that was like “here’s a book for kids about how to make animals/ flowers/ household objects” (and, it turns out, a significant percentage of parenting is making origami dinosaurs to entertain the child). The ones you post seem to be a completely different thing than that- like, the point is to make them because they are mathematically interesting. Really fascinating. Is there a special name for that kind of advanced, math-heavy origami? How did you get interested in it?

@Perfect Number,

My story with origami follows a really common pattern: I tried it when I was a kid, and then later rediscovered it as an adult. When I was in grad school, I received a couple books on modular origami as a gift, and I liked it enough that I kept doing it.

There isn’t any clean division between basic and advanced origami. I specialize in modular origami and tessellations, which are relatively math-heavy, but are not necessarily more advanced than animals/flowers/etc. (often called figurative origami). Figurative origami includes very advanced stuff like the Eric Joisel model I linked to, and there are many basic modulars that I’ve taught to kids. Tessellations have a relatively high skill floor, so I don’t teach those.

Oh cool. I was just thinking about an octahedron thing I made a really long time ago, and I googled it just now and it turns out it was a modular origami thing. Like this https://mathcraft.wonderhowto.com/how-to/modular-origami-make-cube-octahedron-icosahedron-from-sonobe-units-0131460/ That one wasn’t hard but it just took a long time to make all the pieces.

What are the “basic” ones that you’ve taught to kids?

I’ve taught the Sonobe cube, and there’s a variant that only requires three pieces. There’s also “Ray Cube” by Meenakshi Mukerji, “Skeletal Octahedron” by Robert Neale, “Rotating Tetrahedrons” by Tomoko Fuse, and a handful of others.

I notice that a lot of the ways in which you describe origami culture relating to AI art also apply to music–particularly classical music (which I am most familiar with). As with origami, many people learn to play classical music as part of their childhood arts education, and value it more for the satisfaction of performing it than the artistic value of the finished product (I certainly feel this way). Playing music is often understood as something that elevates the player intellectually or artistically, as well as something that brings pleasure to its audience. Copying is the norm for beginners and even professionals can go their entire careers without composing original material. In fact, a lot of audiences would rather listen to music by the established names in the classical canon than anything new. And as with origami, classical musicians and composers throughout history have taken inspiration from folk music and traditional styles that are difficult to attribute to specific creators–though not without controversy (in the appropriation of traditionally Black styles by white composers, for instance).

Of course, while some people experience music as participatory, many others experience it as a product–and some people do care a lot about the effort and artistic genius that goes into music. For instance, I’ve heard of various pop musicians and groups being viewed as unserious or fake for not writing their own songs. The participation-oriented framework and the product-oriented one co-exist a little uneasily in American culture, which can be seen from the fact that the numerous musicians that can’t make a living through performance jobs generally end up as music teachers.

I think it would be pretty easy to make a program that generates Bach chorales, but it would hardly make Bach irrelevant (unless you already thought he was irrelevant to begin with). AI doesn’t keep people from enjoying playing music either. And while AI might have implications for composers, I can’t really see it doing anything to professional musicians that hasn’t already been done by recorded music and streaming. Sometimes, people act like AI is a uniquely bad technology in its potential to disrupt and destroy creative industries when those industries have already been undergoing disruption for decades.