Hilary Rosner has an interesting piece at Wired Science on the campaign to keep the critically endangered Devils Hole pupfish from going extinct.

Background: during the Pluvial period there were a lot of occasionally interconnected lakes in the American southwest, and some of those lakes had little fish in them of what we’d later call genus Cyprinodon. Climate changed, the desert dried up, and desert Cyprinodons found themselves restricted to smaller and smaller bodies of water in the desert. Predictably, speciation occurred when populations were separated, and now five species live in the little bits of remaining fresh and not-so-fresh water in the desert.

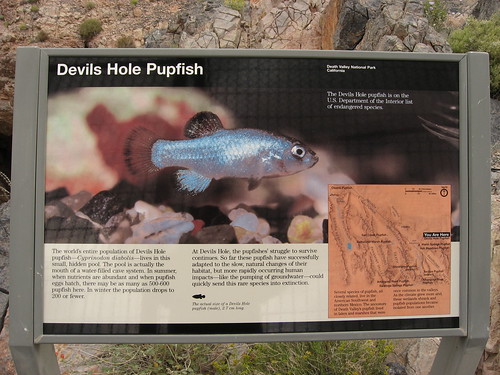

Cyprinodon is a cosmopolitan genus, and many of its member species are doing okay, but desert Cyprinodons are having a tough time, as you might expect of freshwater fish in the desert. The Devils Hole pupfish, Cyprinodon diabolus, is facing the biggest threat of all: its only remaining natural habitat is Devils Hole with no apostrophe, a geothermal spring (92°F/33°C) in a limestone cave in Nevada, with the breeding habitat of the entire species limited to a small rock shelf just beneath the surface of the water. A century of groundwater pumping for agriculture has made that habitat even more tenuous. The fish live a year, and there’s a significant seasonal population crash each winter when less light means less algae. In September, according to Rosner, the global population of Devils Hole pupfish dropped from its usual level in the mid-100s to about 75 individuals.

There’s some question rising whether the Devils Hole pupfish is actually a “good” species, or simply a perpetually starved and overheated strain of the neighboring Cyprinodon nevadensis mionectes, the Ash Meadows pupfish. (Cyprinodon nevadensis is commonly split up into six subspecies, all of them but the extinct Cyprinodon nevadensis calidae still holding on slightly better than their cousin in Devils Hole. As Rosner describes, when an Ash Meadows pupfish somehow snuck into a holding tank with some Devils Hole pupfish in it, the pupfish suddenly started breeding more successfully, and within a few generations all the fish had Ash Meadows ancestry. Predictably, a pupfish biologist has suggested that a few Ash Meadows pupfish be slipped into Devils Hole to reinvigorate the population, and just as predictably others are horrified at the idea.

Rosner’s got a pretty good rundown of the politics involved, though she stumbles a bit in her handling of the definition of “species”:

Martin wants to cross two separate species. That’s supposed to be a no-no. In fact, by one definition of what constitutes a species, it shouldn’t even be possible. Scientists have long thought of species as reproductively isolated units. In the days before Darwin, if two animals couldn’t produce fertile offspring, it meant they were different species. Then things got complicated.… But it turns out that biology doesn’t even adhere to those categories. For example, the ability to reproduce can evolve far more slowly than other traits. So when one species branches off from another, it may still be able to breed with its relatives up the evolutionary tree. “It raises the question, what really is a species? It’s very hard to clearly articulate,” says M. Sanjayan, lead scientist for the Nature Conservancy. “There are lots of things that can breed together but look morphologically and genetically different.” That means scientists triaging endangered species might have more options than they thought.

Rosner seems to be saying that wildlife biologists are largely unaware of the vagaries inherent in applying the Biological Species Concept to real life, which would be news to any of the biologists I’ve met working in the desert. A species is a rough, somewhat arbitrary pigeonhole that we lean on because we want there to be a Basic Unit of Biodiversity. Biologists working in the field to help conserve that biodiversity end up improvising to fill in the gaps in the species concept. For management purposes, species are subdivided into subspecies, varieties, Evolutionarily Significant Units, Recovery Units, and probably half a dozen other terms of convenience I’m forgetting.

All those categories and subcategories are at least partially subjective ways of parceling out a flood of organisms into relevant family groups. Due to those subjectivities, one person’s revitalizing a genetically depauperate fish population with a sibling stock is another’s swamping a native population with an invasive exotic fish species.

As Rosner points out, the issue is relevant beyond the steep walls of Devils Hole. I spent the weekend at a meeting of the Sierra Club Desert Committee, listening to activists and agency staff give updates on regional environmental issues, and one of those updates was on plans by the US Fish and Wildlife Service to start depopulating the controversial Desert Tortoise Conservation Center. There are about 2,700 tortoises at the center south of Las Vegas, most of them collected in the years when Vegas was busily sprawling out into the desert, but a substantial minority consisting of surrendered pets and their offspring. The Center, which is run by the San Diego Zoo, is overrun with torts. Before the San Diego Zoo took over management a few years back, there were so many tortoises there and such poor veterinary management that some desert wildlife biologists referred to the place as the Desert Tortoise Concentration Camp. Everyone I’ve talked to about the place says the Zoo has made things a lot better. Still, taking care of three thousand torts is expensive, so the Center wants to release some of the healthier ones into what it deems appropriate places: 17 wilderness areas, five wilderness study areas and other land in Nevada, including a stretch of land in the northern Ivanpah Valley that’s already had 9,000 tortoises relocated there.

Tortoises have recently been split out into two species, one for each side of the Colorado River. Within the western species there’s a whole lot of regional genetic diversity, unsurprising for a long-lived, slow-moving species that prefers not to migrate far from its home territory. Tortoises in Southern Nevada have a fair bit of genetic distinctness from those in California’s Colorado Desert, and they’re both distinct from torts in the West Mojave near Los Angeles. Historic attempts to translocate tortoises from one place to another have been done with those genetics in mind, for the most part.

That seems to be a thing of the past, though. The USFWS representative at the meeting pointed out that the resources aren’t there to scrutinize each released tortoise’s genome; apparently, the Center’s answer is to eyeball each tortoise and figure out whether each one looks Nevadan. Problem is, many of those surrendered pet tortoises might well have come from the extreme western edge of the species’ range, several Recovery Units away. Records are lacking.

So like with the Devils Hole pupfish and its neighboring cousins, the question becomes: to what degree do we preserve the local native genome of a population? It’s very likely that local populations of tortoises have some traits that serve to help the animals contend with local conditions, but other traits may well be a fluke of inheritance. Where do we draw the line?

See if baraminology can help…

Oh, right, it can’t.

Glen Davidson

“What is a species, anyway?”

Not being a biologist, I consider a species to be an interbreeding population that’s sufficiently distinct from other populations.

(What the criteria for sufficient distinction may be, however, seems to vary between people)

If the premise is that more variety is better, then the line should be drawn by pragmatism according to resource restrictions, i.e. an optimisation problem.

How does one say “prime directive” ala Star Trek?

I remember a conversation vaguely similar to this starting up about the Red Wolf, where defining whether the red wolf was a separate species in itself or ‘merely’ a crossbreed between the grey wolf and the coyote would have significant effects on legal treatment.

Then again, canines are a serious mess to anybody attempting to define the limits of ‘species’.

Bonus weirdness – Different *genera* can hybridize. Right now in lab I have hybrids between a rat snake (genus Elaphe or Pantherophis, depending on which taxonomy you believe) and a king snake (genus Lampropeltis), and these hybrids are actually capable of reproducing with each other, and have produced up to F4 offspring with no noticeable reduction in fertility or increase. Based on comercial breeder’s stock, it seems like most North American members of subfamily Colubrinae can make fertile hybrids in captivity, and one recent paper reports such individuals from the wild. In the case of the most distant cross (the one I have), the lineages have been separate for almost 20 million years.

Still stranger – there are apparently fertile hybrids of Alligator Gar and Longnose Gar, which have been separate for 180 million years according to molecular dating. Sadly, 12-foot fish don’t make good subjects for breeding studies.

This is the kind of article I started reading Pharyngula for. More, please! :)

Chris, I saw http://maddowblog.msnbc.com/_news/2012/11/21/15337943-political-metaphor-waits-to-happen-devils-hole-pupfish-edition?lite on the Maddow blog, and was coming here to let you know about it. A few more pics, and even a vid.

There are some of the same questions about the peninsular bighorn sheep in the Santa Rosa Mountains above Palm Springs, California. Are they a separate subspecies or are they all the same species, Ovis canadensis nelsoni, as the sheep on the other side of the Coachella Valley in Joshua Tree National Park. It is partly political because it is important to keep the idea that the peninsular bighorn sheep are unique and need more protection.

Biodiversity is important, but it shouldn’t trump other concerns. If tortoises played an important role in the local ecology and they are now missing, bringing some back, even if they’re the wrong species or subspecies, is better than tortoises simply being absent. And tortoises getting to live in something more like their natural habitat rather than a crowded zoo is more important than species purity which might be an impossible goal anyway.

I’ve volunteered with groups that help out with cleanup and protecting important habitats. But one task I’ve avoided is native species removal. I’m not going to hurt my back to pull out plants that have nice smelling flowers just because they’re on the wrong side of the mountain. And I hope people at least see keeping some sort of local fish in Devil’s Hole as at least more important than making damn sure it’s the right local fish.

My understanding is that the population of Devils Hole Pupfish is relatively stable. Biggest recent issue was some monitoring equipment falling onto the shelf, killing some fish.

It’s also unclear from the information if the Ashland Creek Pupfish introgresses with the Devils Hole Pupfish. Since I take my understanding of these characters from Hubbs and Millers work, they are separate taxa, thus separate species.

Really great relict species, but what does not get mentioned are the species which extend south into Mexican drainages other than the Colorado River, and I think there may be a species on one of the larger Caribbean Islands or the Bahamas.

Mike

Second comment:

The reason you do not wish to cross the populations in the wild is the information content of the time of divergence provides clues as to when particular climatic events arose in the pluvial.

Mike

I love Cyprinodontids. Interesting little fishes.

My (vastly uninformed) opinion on the subject of the post: I think it’s better to try to keep the lineage of C. diabolus whether we call it a proper species or not. Surely there are some captive breeding populations of this morph. If a bad year comes and C. diabolus goes finally extinct in the wild it should be pretty easy and inexpensive to perform a reintroduction from these stocks.

There are an awful lot of ways to define what the criteria are. Here are just 26 of the most popular of them.

@4: Yes, that has always been my question–why is a wolf a separate species from an Alaskan Malamute, but a Chihuahua is not?

I thought all domestic dogs are the same species as wolves, so that should include Alaskan Malamute…?

The comment about the Star Trek prim-directive is interesting. I can see the whole question of which animals we reintroduce or release into the wild also brings up the question of how much do we interfere in the wild areas and what effects on the evolution of the existing populations would we cause. There would not be any problems at all if we had not caused the disappearance of wild populations in the first place or ended up with a whole lot of captive animals from threatened species we do not know what to do with.

It looks like it is a little late in the day to worry about not effecting anything, we will have to manage these wild lands and their populations until we either kill all of them or are reduced in numbers such that we do not effect them any longer.

I do appreciate all the details that need to be addressed to do this management in a more or less benign and effective way. That there is a concern about doing that carefully is a very nice thing to be thinking about before thanksgiving. because we are indeed doing it.

uncle frogy

It’s true; all kinds of shit can happen in unnatural captive situations. As mentioned, snake breeders have gone to town with this. I also know of hybrid offspring of wood and Blanding’s turtles (Glyptemys and Emydoidea or Emys, respectively). I hadn’t heard about the gars before, but poking around it looks legit.

That’s why Mayr’s Biological Species Concept sez a species is “a group of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations that is reproductively isolated from other such groups” [my emphasis].

It’s a definition that’s far from perfect, but it’s in no way violated by captive hybridization, nor even by rare natural hybridization. And in all the animals mentioned, natural hybridization is very rare to evidently nonexistent. I’d also argue that four generations of fertility under captive conditions is interesting but irrelevant. There’s no way to know how those hybrids would fare in an ecologically and evoloutionarily meaningful situation.

As for genera (and subfamilies, etc.), they’re far more subjective and arbitrary than the vast majority of recognized species (I’m talking about animals). Genera and higher taxa are fictive pigeonholes of convenience, opinions often influenced mostly by what’s extinct, whereas most biologists would agree that most species, of animals or anyway vertebrates, are real things, meaningful units.

Whatever it is. anyway.

Tense fail: sub ‘Whatever they are, anyway.’

Not tense. duh

The point isn’t whether or not it is a separate species, but rather how do we stop the environmental destruction being done by excessive pumping of ground water? If the way things are set up legally so that the easiest way to stop the destruction is to claim the fish is a separate species, then so be it. The problem is that we can’t stop environmental destruction just because the environment is being destroyed. It has to fit into the legal code.

ChasCPeterson–Captive breeding results are relevant to the biological species concept in every case in which we are dealing with non-sympatric populations, unfortunately. At least, the standard view on the biological species concept is that geographic isolation -doesn’t count- as reproductive isolation*, and thus does not indicate distinction at the species level. So, if critters don’t occur together and we want to know whether they are reproductively isolated… captive breeding is all we’ve got. Even though we know it isn’t a very good proxy for determining what might happen in nature if the presently disjunct critters did not happen to be disjunct.

*And for good reason. It would make a hash of everything in places like the western U.S. with a lot of topography &c. giving lots and lots of little isolated habitats. Delimiting species would become a fantastic mess of guesswork about whether or not particular habitats are connected enough that interbreeding could happen, or not. At the other end of the variation in landscapes, you have places like the eastern coast of the U.S.–we create new species every time we bulldoze a nice new subdivision through a patch of habitat, since we now have two disconnected patches of habitat…

IMO, the problem of what to do with non-sympatric populations is enough to kill the biological species concept as any kind of workable approach to delimiting species in practice. It just doesn’t work.

However, returning somewhat to the original issue in Chris Clarke’s article…

First, IMO our current procedure for determining which critters deserve protection and which don’t is not particularly scientific to start with. There are well-known taxonomic biases–vertebrates are more likely to be protected than plants, which are more likely to be protected than invertebrates, which are more likely to be protected than fungi, and on down the line. The non-taxonomic designations used in vertebrates (but, so far as I know, never in any other critters) exist, so far as I can tell, to allow that trend to extend far beyond the available data (if some segment of a species is demonstrably distinct from other segments of the species, it gets recognized as a subspecies or a segregate species; if -not-, but we still think it’s distinct and needs special protection nevermind what our data say, then it’s a “recovery unit”). Worrying about how to define a species in this context is fairly irrelevant. Basically, we protect things to which we have emotional attachment, or if protecting them serves some other goal (e.g., killing development projects you don’t like). Trying to shoehorn taxonomy or non-taxonomic designations to support that decision after the fact is just legalistic smoke and mirrors to please the bureaucrats. At the end of the day, our conservation decisions are not based on any objective evaluation of what organisms actually are rare and in need of conservation action. Conservation is political and emotional, not scientific.

An unrelated point–if different populations of a species have some genetic variation linked to local adaptation, well, so what? Natural selection is self-repairing. Dump some ill-suited California genes into Nevada turtles and… well, OK, it’s -possible- for those genes to spread anyways and make the Nevada turtles worse off, but it’s very unlikely. The reasonable expectation is that if you dump those Californian genes into the Nevada gene pool… well, if they don’t work in Nevada, they’ll disappear. Problem solved.

Nah.

That’s true as far as it goes–hence the “actually or potentially interbreeding” part of the definition.

(On the other hand, although alone it’s not a reproductive isolating mechanism, geographic isolation is usually a prerequisite for their evolution; Mayr again.)

1) What? Are you wholly unfamiliar with the wonderful things those clever scientists are doing with molecular genetics these days?

2)Practically, afaik nobody ever uses captive breeding success to judge whether or ot two animal populations should be designated as separate species or not.

I’m actually sympathetic to much of what you’re saying, but wow, that’s wildly overstated. It’s also a direct insult to a lot of dedicated and hard-working scientists.

ChasCPeterson–

“That’s true as far as it goes–hence the “actually or potentially interbreeding” part of the definition.”

Well, yeah, but “potentially interbreeding” is basically just a cue for speculation. You get to guess whether critters would interbreed if they occurred together.

“1) What? Are you wholly unfamiliar with the wonderful things those clever scientists are doing with molecular genetics these days?”

Molecular genetics can tell you a lot about the history of interbreeding between groups of organisms. However, unless we have shloads of ancillary data (e.g., a thorough understanding of the genetics of the various possible methods by which reproductive isolation can occur in a particular group of species), it simply cannot tell you whether or not critters -can- interbreed.

Historical absence of interbreeding does not equal reproductive isolation. It’s that “potentially” again…

“2)Practically, afaik nobody ever uses captive breeding success to judge whether or ot two animal populations should be designated as separate species or not.”

True. In practice, essentially no one ever uses the biological species concept to make taxonomic decisions.

Chas

I think if you read it as

“Conservation decisions [are] political and emotional, not scientific.”

It makes sense.

My geology professor seems fond of the saying:

“The rocks don’t care about your definitions”.

A species is whatever we define it to be. Our friend Rosner needs to remember that those definitions aren’t rigid and impermeable, because (most) organisms don’t really care where we try and put those lines.

As for the Devil’s Hole Pupfish, I don’t really see a problem with introducing some new genetic material to such a small population, especially if the species is on the verge of extinction. Hybridization may cost some of the “uniqueness” that the species holds, but it’s better than them dying out entirely.

ChasCPeterson–“I’m actually sympathetic to much of what you’re saying, but wow, that’s wildly overstated. It’s also a direct insult to a lot of dedicated and hard-working scientists.”

Huh? Scientists don’t control politics. Conservation actions are political.

For instance, species get placed on the federal endangered species list by some folks at the US Fish & Wildlife Service. USFWS is not tasked with examining the complete biodiversity of the US and determining population sizes and population dynamics for each species to determine which are under threat and which aren’t. Neither, for that matter, is anyone else. Instead, the USFWS is simply tasked with examining the petitions sent to it by political advocacy groups to decide if they contain sufficient evidence to warrant endangered species listing. They see what’s sent to them by the political advocacy group, maybe do a quick check of NatureServe, and that’s it. It’s bureaucratic review of a political proposal. Sometimes, there are scientists behind the scenes at the political advocacy groups. Sometimes there aren’t. There certainly are some scientists in the mix doing great work, but not enough of them, and not consistently enough across the board (how many people do you know of working on the conservation of rare tachinid flies?), to ever create any kind of synoptic, objective evaluation of rarity of species or efficacy of conservation action. Moreover, the scientists are generally constrained by political funding decisions–conservation money mostly goes to research on species already known to be rare.

Krazinsky–

No apostrophe, “Devils Hole”. :-)

I think nowadays dogs are classed as a subspecies of the gray wolf. When I was a kid, I learned the major taxonomic ranks by memorizing my favorite animals’ taxa. In those days cats were Felis catus and dogs were Canis familiaris; now they’re Felis silvestris catus and Canis lupus familiaris.

As a microbiologist I’m always amused at the zoological obsession with the word “species”, and welcome Chris Clarke’s excellent post reminding us that species are convenient, but somewhat arbitrary, man-made pigeon holes that aid biological understanding. In the bacterial world where most of the bugs don’t breed (they just mitose) the handy Biological Species Concept is a non-starter. Even many fungi have no sexual cycle, thus throwing taxonomists heavily on to a mix of morphological (traditional) and molecular genetic (not so easy to interpret as sometimes made out) information to define species boundaries. The rate at which microbiologists are currently defining new species compensates a lot for the perceived species loss among larger, more cuddly organisms.

In the Galapagos Islands’ center for giant tortoises, the 11 surviving sub-species (each island has generated a morphologically distinct sub-species) are fastidiously kept separate to avoid the loss of any more (originally 14 sub-species were defined). This seems to be taking the sanctity of the Biological Species Concept to an extraordinary level (and certainly the opposite of what CC is describing for the Devils Hole Pupfish).

Thanks a lot for the post, Chris Clarke. We need frequent reminders that the holy “species” is not a natural biological unit at all.

Chris,

The discussion about the pros and cons of un-natural interbreeding is very interesting but how do you feel about re-creation of extinct species? In other words, the creation of a new species really e.g.interbreeding to re-create the quagga? Do you think this was ethically valid?

Please answer in non-sciencey terms as I am not a scientist nor do I play …..

franko–

“We need frequent reminders that the holy “species” is not a natural biological unit at all.”

Certainly a lot of microorganisms do not seem to have natural units identifiable as species. We do not have any species criterion that really works reliably on asexual lineages. For the majority of macroscopic (and mostly sexual) organisms, I think you can make a pretty good argument that natural species can be identified.

However, in all groups there are grey areas, at least…

sueboland, good question, if slightly out of topic.

As another non-scientist, I would have no ethical qualms (I’d be delighted!) for the resurrection of species that humanity has made extinct subject to their reintroduction not further destabilising extant ecologies*, but would find the resurrection of those who have gone extinct due to natural processes more problematic.

(Also, I don’t find the Jurassic Park scenario particularly plausible)

—

* Even if they had to be kept in refuges or even zoos due to their native habitat having disappeared. :|

The short answer is, “In the wrong place, inevitably.”

It’s the sorites paradox made real, as is the debate about when it’s OK to abort a foetus or how old one should be before being able to consent to have sex. You can point to one extreme and say “This is definitely wrong.” and point to the other extreme and say “This, also, is definitely wrong.”, but we are uncomfortable with the idea that there is simply no single place in between that is “right”. We need to become more accepting of fuzziness.

We demand rigidly defined areas of doubt and uncertainty!

I feel a need to explain: by “both wrong” in the previous examples I mean:

Setting limit for abortions at 0 weeks = wrong.

Setting limit for abortions at 38 weeks = wrong.

Setting age of consent for sex at 5 years = wrong.

Setting age of consent for sex at 25 years = wrong.

Did not mean “abortion is wrong” or “sex is wrong”. Wouldn’t want it interpreted that way (although I’d hope it was obvious…)

Chris, lovely article.

@34: Humans are as much part of nature as a big honking asteroid or a supervolcano erruption. Species have gone and will go extinct at the “hands” of other species, and it really doesn’t matter whether the other species is homo notso sapiens.

Life doesn’t care how humans look at it. Classifications are tools to help us make sense of what we observe. Take female vs. male, a nice workable classification, apart from the fact that it doesn’t apply to anyone of us when looking close enough. Like so many characteristics, gender is a spectrum. And while it makes sense to group, order and simplify to help us think more clearly, forcing people (and pupfish) to conform to these simplifications causes unhappiness, anguish, pain and even loss of life.

The individual pupfish doesn’t care one jot about its genome, it cares (in the most unanthropomorphic sense possible) about being alive, staying alive, and reproducing.

Excellent article, very interesting subject. Thank you.

We must, at all costs, maintain the purity of the Devils Hole Pupfish race!

Thank you for another interesting article about endangered species.

I enjoy these forays into the world of conservation, and the discussions that follow in comments are also fascinating.

Thanks for continuing my education! :)

Franko:

Seeing as there is a microbiologist in the comments, thought I might ask something that I have always wondered about. According to the Catalogue of Life, there are currently 9,072 named species of bacteria and 281 species of Archaea. This seems to be a large underestimate of what is actually out there. I was curious, how many species of prokaryotes do you think could be living on earth today? And are new species discovered within these groups every year with as much regularity as say, insects or teleost fishes?

How you define species is entirely up to you by the way since you guys seem to classify your organisms in a different way to the zoologists and botanists.

Hi woodview. Good question. A disclaimer, I’m a specialist in human pathogenic fungi rather than bacteria, but for what it’s worth…

Undoubtedly the number of known prokaryote species is an underestimate. But guessing how great an underestimate is not easy and — as you’ve picked up — it depends heavily on species definitions. There are many studies from around the 1990s which use the base sequences of 16S ribosomal RNA to suggest that, for example, there may be 1000s of times as many bacterial species in the human gut flora, samples of soil, etc. than are ever detected by growing the wee fellas in culture. But this sort of thing depends on how a species is defined. Some folk use <97% DNA sequence similarity as a species definition. Yet bacteria may achieve that level of sequence variation in response to environmental factors (a touch of Lamarckism?) so it would be presumptuous to make estimates of numbers of species based on this 'viable but non-culturable' approach.

A lot of new microbial species result from splitting formerly single species (this applies to bacteria and fungi). One beautiful example of this is to be seen in the paper by Fisher et al. (Mycologia 2002;94:73), who use molecular approaches to split the species of fungus that causes San Joaquin Valley Fever into two, even though there's not a jot of morphological differences between the two species. Tracking the two species shows how their divergence accompanies known human movements through the Americas. The URL for the paper is http://www.mycologia.org/content/94/1/73.full.pdf+html but I'm not certain it's on open access.

sueboland:

My two cents on that one–never mind the ethics, it just isn’t possible. Interbreeding among extant species will not recreate an extinct species. It’s like trying to recreate Thomas Jefferson by finding a modern humans who look a lot like him and convincing them to have children together. You might get a child that looks a lot like Thomas Jefferson, but you’re not going to get Thomas Jefferson.

Ethically, I suppose trying to re-create a quagga is precisely equivalent to any other situation in which we try to get critters to reproduce in captivity. It’s also just a pointless exercise…

Franko, thanks for the response. I had a feeling this would be an ongoing problem for microbiologists. I do have open access through university so will check out that paper. Would biochemical pathways be a useful way to assess diversity in prokaryotes seeing as for what they lack in morphological variation, they make up for in their ways of obtaining energy (e.g: photosynthesis, methanogenic bacteria, nitrogen fixing, etc)?

Wow, Woodview, you just reinvented numerical taxonomy! The marvellous Peter Sneath, back in the 1950s, had the idea that if you measured enough properties of a particular bug you could compute its level of similarities and differences from others and thus define species boundaries. He developed the idea in collaboration with Robert Sokal. Ideally hundreds of properties needed to be measured: ability to grow on a large number of single carbon and nitrogen sources — effectively biochemical pathways as you say. Sneath’s original idea was that two bugs with, say, more than 90% similarity in a large number of biochemical tests could be defined as a species. In practice, the real world never behaved as nicely as the concept, so no %similarity ever emerged as a universal species definition. But the approach was used in massive amounts of bacterial taxonomic research through the 70s and 80s.

One great spinoff of the efforts was the 1963 book “Numerical Taxonomy” written by Sneath and Sokal. The mathematical principles of statistical clustering these guys invented still lie at the back of today’s highly sophisticated methods for drawing trees of life and the like.

Phenotype-based approaches to microbial taxonomy are steadily giving way to DNA sequence analyses. But with these, as ever, nature refuses to behave in quite the ideal way one might like. Ultimately, the message from Chris Clarke’s OP should be that in ALL living forms, not just bacteria, there’s a gradation of difference of properties such that humans can never entirely succeed in defining rigid boundaries (species) on what is in effect a continuum.

Bill @37:

Well yes, but to claim that since humans are part of nature nothing humans do is other than natural is not just to elide the very concept of artificiality, but to deny responsibility for what humans have done on the basis that it’s merely natural.

More to the point, since the original question was couched in terms of ethics, my response was in those terms.

In short, if we broke it, then I think it’s our responsibility to fix it, if such an outcome is seen as worthwhile*.

(If not us, then whose?)

But humans do care how humans look at it (there’s evidence for that in this very conversation!).

—

* And yes, in the longer term, what humans did or didn’t do won’t matter one whit, since we shan’t be around.

With regards to breeding the two subspecies of pupfish/ letting one die and the forseeable cliched “Oh the horror!” reactions as both sides view the situation as black and white and begin the inevitable in-fighting, my question is this: does it really matter?

We had a similar reaction to a situation here in Britain where an invasive species, the American “Ruddy Duck”, was interbreeding with the native “White-headed Duck”, and doing so so successfully that the White-headed Duck was (and I believe still is) in serious danger of being bred out of existence, leaving only the mixed-breed offspring and true Ruddys. There was a massive uproar about this and lots of conservationists were blowing a gasket and demanding that something be done to save the White-headed Duck. My opinion was, and still is, “well… isn’t that evolution?”. The same, or something similar at any rate, applies here. If this species turns out to be an evolutionary dead end and they die out, well I’m afraid that’s how nature works. It’s funny how most conservationists are so against meddling with nature… up until the point that nature does something they don’t like.

So my point is this: if introducing some genetic diversity into that population is what’s needed to save it, and you are set on saving it… then do it. If you don’t do it, they are going to die out; that’s how nature works. Personally, I’d leave it alone. Species do die out, it’s an unfortunate fact of reality. But also, as in the case of the ducks, new ones are created. It happens all the time and that dynamism is part of what makes life so beautiful.

In my opinion, life is big enough and old enough to look after itself and we should be doing all we can to leave things alone so that they can proliferate and diversify and yes, in some cases die out, as they please. This involves not dumping pesticides in rivers, it means not catching every damn tuna in the ocean with oversized nets; it means not killing all the top predators because you want to raise some cattle on their territory and, in some unfortunate cases, it means leaving some species that couldn’t cut it to die out quietly. We’d all be severely pissed off with a wildlife cameraman if they decided to scare the Cheetah away because the Gazelle was “just too cute to die”, and I don’t see how this is any different. So conservationists, stop arguing about this and go out and try stopping some of the grievious crimes against nature listed above rather than worrying about the 75-200 remaining members of a species that happened to draw the evolutionary equivalent of the short straw.

@franko #45

I’ve never heard of Numerical Taxonomy, thanks for that. I was wondering; clearly the technique doesn’t work based on physical similarities but could it be used to classify species based on genetic similarities? We’re already at a stage where we can say “Humans and Halibut share X% of their genome”.

@bradleybetts #48

In John Wilkins’s excellent list of 26 different species concepts (http://scienceblogs.com/evolvingthoughts/2006/10/01/a-list-of-26-species-concepts/) you’ll find the work of Sneath and Sokal listed under #22: ‘phenospecies’. In one of the comments it’s pointed out the the ‘operational taxonomic unit’ as defined by the numerical taxo people is the equivalent of a phenospecies.

The concept is indeed used to classify species based on genome sequence similarities. And the clustering statistics used to provide your huma/halibut example all derive from the 1960s numerical taxonomy work. In principle it should be a piece of cake to compare two genomes and declare %similarity, particularly now a whole genome can be sequenced rapidly and cheaply. But there’s a catch. Most of the DNA in every genome is non-coding stuff referred to (until very recently) as junk DNA. So when you compare organisms A and B (halibut and human — your example) do you compare ALL the DNA, in which case you get a lot of dissimilarities, or just the DNA in definable genes (open reading frames or ORFs; a term you may have seen) that actually encode proteins? If you choose the latter, what do you do about the situation where halibut has a few genes you just don’t find in humans and vice versa? It’s this sort of problem that means, at present, we’re still heavily dependent on taxonomy based on genes that are pretty ubiquitous throughout living organisms — or at least common among all animals or all plants, etc.

All of this serves only to re-emphasive what Chris Clarke was originally driving at. We don’t have perfect species definitions. I’d go further and say we probably never will.

Franko, thanks for answering all my queries. I learnt quite a bit and I’m surprised my suggestion was already seen as a concept for identifying species! Pharyngula really does have some of the most knowledgeable commentators on the internet, I always learn something from them.