Fans of author James Joyce and his novel Ulysses celebrate today (June 16th) because it is the day in which all the events of the book take place and it has come to be known as ‘Bloomsday’, named ofter one of the key characters in the book Leopold Bloom.

Ulysses is a modernist novel by Irish writer James Joyce. Parts of it were first serialized in the American journal The Little Review from March 1918 to December 1920, and the entire work was published in Paris by Sylvia Beach on 2 February 1922, Joyce’s fortieth birthday. It is considered one of the most important works of modernist literature and has been called “a demonstration and summation of the entire movement.”According to Declan Kiberd, “Before Joyce, no writer of fiction had so foregrounded the process of thinking.”

Ulysses chronicles the appointments and encounters of the itinerant Leopold Bloom in Dublin in the course of an ordinary day, 16 June 1904. Ulysses is the Latinised name of Odysseus, the hero of Homer’s epic poem the Odyssey, and the novel establishes a series of parallels between the poem and the novel, with structural correspondences between the characters and experiences of Bloom and Odysseus, Molly Bloom and Penelope, and Stephen Dedalus and Telemachus, in addition to events and themes of the early 20th-century context of modernism, Dublin, and Ireland’s relationship to Britain. The novel is highly allusive and its prose imitates the styles of different periods of English literature.

Since its publication, the book has attracted controversy and scrutiny, ranging from an obscenity trial in the United States in 1921 to protracted textual “Joyce Wars”. The novel’s stream of consciousness technique, careful structuring, and experimental prose – replete with puns, parodies, and allusions – as well as its rich characterisation and broad humour have led it to be regarded as one of the greatest literary works in history; Joyce fans worldwide now celebrate 16 June as Bloomsday.

Really devoted fans will spend the day dressed up as characters in the book and walk through the streets of Dublin, recreating the path taken Bloom using the clues that are buried in the book. Other festivities include marathon readings of the novel that can last up to 36 hours.

The style of the book makes it difficult to read. Since my education in Sri Lanka was heavily in science and mathematics and had no literature component whatsoever after eighth grade, I never encountered any of the canonical works of literature in my formal education and had to fill in the gaps on my own in adulthood. While I have managed to read many of them, I failed with Joyce. I took a stab at Ulysses but gave up fairly quickly into the book. It may be one of those books that you need some expert guidance to appreciate, perhaps in the form of a class with a knowledgeable teacher.

Brianna Rennix has an entertaining essay explaining how the book should be read to get the most out of it and that Joyce himself encouraged the idea that it was deliberately made difficult.

Even after the publication of Ulysses cemented Joyce’s public reputation as a literary giant, he often talked about the book as if it were a kind of long con. “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant,” Joyce told one reader, “and that’s the only way of ensuring one’s immortality.” To another, he declared: “The demand that I make of my reader is that he should devote his whole life to reading my works.”

So: Ulysses isn’t meaningless, but its own author seems to acknowledge that it is, at least partly, a book designed to frustrate easy comprehension.

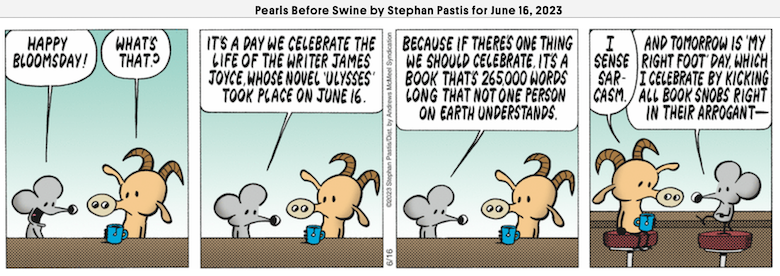

Cartoonist Stephan Pastis is not a fan of novels that are difficult (and definitely not a fan of this book) and rarely misses an opportunity to say so, and so commemorates today in his own way.

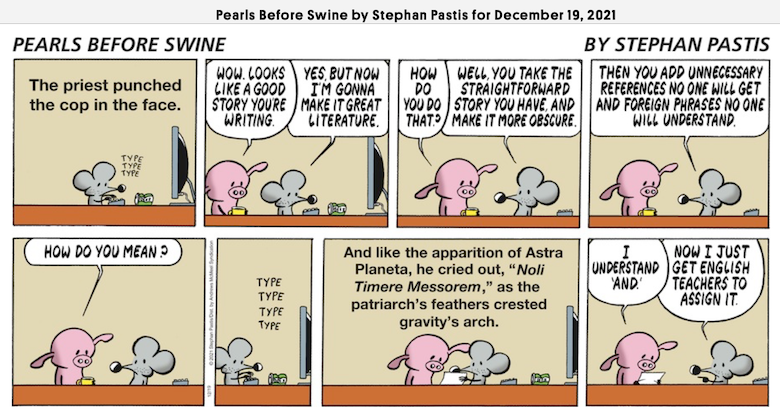

Here is another cartoon from back in 2021.

I found this book impossible to read, and I had an explanatory guide beside me when I tried. I’m not at all sure that the guide-author themselves -was aware- of how incomprehensible and inconsistent that they themselves were. I shoved it into the category of pate de foie gras in my mind: a disgusting icky product made in a horrible inhumane manner that people can pretend to like for ¿virtue? signalling purposes.

Descriptions of the book have certainly never tempted me into giving it a shot.

When I write I keep in my mind what Dave Pollard (How to save the world) said.

To me a good story, like any piece of good art, has seven essential qualities:

(1) it gives pleasure,

(2) it provides some fresh understanding,

(3) every sentence in it counts (no padding),

(4) it takes a camera or “theatre” view (says what was said and what objectively happened without any interpretation or judgement),

(5) it respects the audience’s intelligence (no manipulation or deliberate obscurity),

(6) it leaves space for the audience (to fill in their own details), and

(7) it must be in some way really imaginative, clever, or novel.

I’ve only read bits and pieces, and they were OK, but not OK enough to make me want to read the whole thing. I’ve certainly read more conventional novels that were far worse/more annoying.

The problem for many people might be expectations. Most novels are narratives presented in an established format. Here we have the often random thoughts of the protagonist. That can be engaging, if you turn off the “yes, but what happens next, and where is this going” switch.

Joyce might be confusing, but I find some more widely-acclaimed authors infuriating.

The Irish are good at weird fiction. As a gentler intro, I recommend At Swim-Two-Birds, by Flann O’Brien.

I have read bits of Joyce’s Ulysses, and concluded he was drinking way too much Absinthe.

I’ve read the Odyssey, which is a great story, though it is easier to understand all the characters actions if you have some familiarity with Ancient Greek culture and mythology.

Tethys @#5,

But doesn’t absinthe make the heart grow fonder?

Mano @6 ~

My mother, who died of brain hemorrhage in January of last year, loved puns, much to the dismay of the entire family. Every time you drop one -- your own or another’s -- it brings these memories flooding back, and I thank you for that. Though I may reflexively groan, it comes from a place of appreciation and reminiscence.

@Mano

Well played! : D

TGAP Dad @#7,

I am sorry to hear about the death of your mother.

It is interesting that she loved puns. She and I would have got on well. It has been my experience, however, that the people who like puns tend to be male for some reason.

I myself tried it, but gave up rather quickly.

Most certainly not my cuppa.

Similar, in my estimation, to The Song of Hiawatha.

Esteemed by the cognoscenti, apparently.

(Like a gourmet likes rotten fish, I suppose)

Never been a fan of anything considered “great literature”. Which is a hit funny considering how much I’d read other books even in the middle of class (surprising my teachers when they’d call on me and I’d still answer the question right). Going on the AP Lit track in high school was the worst mistake of my life and I’m sure what a contributor to my severe depression at the time. My teachers had persuaded me I might “enjoy the challenge”, but now I know that that is only true if you crave more of the subject. If you just want to avoid it, challenge is soul-grinding.

The worst book was The Great Gatsby. I got so zoned out “reading” it (literally just seeing the words jnstead of reading them) that when I got to the part where they were talking about Gatsby’s death I got surprised and didn’t know what they were talking about. I had to read the last chapter about 5 times because even when I was trying to pay attention I couldn’t stop myself from zoning out and skipping over it.

@ Mark Dowd

That makes me chuckle, because to this day I have never come across a greater work of modern literature than The Great Gatsby.

The ending when Fitzgerald makes it explicit that Gatsby is a metaphor for the failure of the “American Dream”, and that our lives are largely an attempt to realise the dreams of our youth, is still to this day some of the most powerful modern prose I’ve read.

Fitzgerald was an alcoholic, but a great writer.

Anyway, YMMV, but I wish I could write like that.

Keep in mind this was before 8th grade so I was only 13 at the time. And it was a book I was told to read instead of one I chose to, so there’s bias there.

I had the same reaction to Gatsby at age 17. It’s one of two books that were assigned reading that I had to force myself to finish. It’s soooooo boring, the characters are idiots, and in the end nothing happens. Atlas Shrugged was the other book where I kept waiting for something to happen, and the reward was 40 pages of whinging speech that remains the most tedious thing I’ve ever encountered in ‘Literature’.

I’m currently having the same problem with Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments. (I figured I should probably read it sooner or later, and it’s quickly becoming later rather than sooner.)

My problem is not really with the 18th Century prose itself, but rather that Smith keeps saying the same thing over and over again. I wish he’d make his point and move on. He doesn’t need to make the same point with different words numerous times; I got it the first time.

I’ve made several attempts at Ulysses, and failed each time. I am unlikely to try again -- too much else I really want to read, although mostly history rather than fiction these decades. I remember enjoying Joyce’s Dubliners (short stories) and A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (autobiographical fiction). One of the books of fiction I do want to read is Dylan Thomas’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dog -- he rather implausibly denied the title was a take-off of Joyce. Following this chain of free associstion a stage further, if you’ve never listened to Thomas’s “play for radio” Under Milk Wood read aloud by Richard Burton, it’s a real treat.