The monthly reports with the numbers of new jobs created and the level of unemployment are watched closely as important signs of the health of a nation’s economy. When large numbers of jobs are created and the unemployment figures go down, that is taken as a sign of a growing economy and less hardship.

But one thing that has always bothered me is the lack of attention in the media to what kinds of jobs are being created and what wages and benefits they provide. If a recession drives a million people out of work and the recovery brings a million jobs back at lower wages and fewer benefits, then clearly, despite superficial appearances, we have not returned to the status quo. So when job numbers are reported, it is good to bear in mind that the nature of the jobs and what they pay should be part of the analysis of whether people’s lives are getting better or not.

Erin Hatton, an assistant professor of sociology at the State University of New York, Buffalo, looks closely at the kinds of jobs currently on offer and is not sanguine about the current economic ‘recovery’.

Politicians across the political spectrum herald “job creation,” but frightfully few of them talk about what kinds of jobs are being created. Yet this clearly matters: According to the Census Bureau, one-third of adults who live in poverty are working but do not earn enough to support themselves and their families.

A quarter of jobs in America pay below the federal poverty line for a family of four ($23,050). Not only are many jobs low-wage, they are also temporary and insecure. Over the last three years, the temp industry added more jobs in the United States than any other, according to the American Staffing Association, the trade group representing temp recruitment agencies, outsourcing specialists and the like.

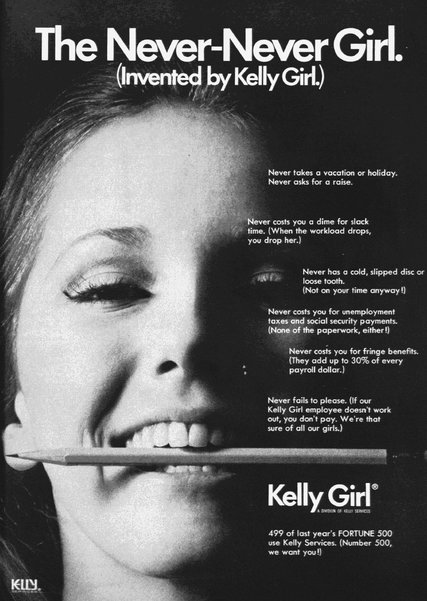

How did this come about? Hatton discusses how, starting right after World War II, a long term trend of driving wages and benefits down was spearheaded by temp agencies that promoted non-union, low-wage, benefits-free, and expendable female workers to employers as a means of cutting costs. This ‘Kelly Girl’ ad from 1971 shows how the idea was sold to employers. (There is something weirdly disturbing about the image of a woman with a pencil in her mouth, like a horse with a bit between its teeth.)

Hatton continues:

Protected by the era’s gender biases, early temp leaders thus established a new sector of low-wage, unreliable work right under the noses of powerful labor unions. While greater numbers of employers in the postwar era offered family-supporting wages and health insurance, the rapidly expanding temp agencies established a different precedent by explicitly refusing to do so. That precedent held for more than half a century: even today “temp” jobs are beyond the reach of many workplace protections, not only health benefits but also unemployment insurance, anti-discrimination laws and union-organizing rights.

…

The temp industry’s continued growth even in a boom economy was a testament to its success in helping to forge a new cultural consensus about work and workers. Its model of expendable labor became so entrenched, in fact, that it became “common sense,” leaching into nearly every sector of the economy and allowing the newly renamed “staffing industry” to become sought-after experts on employment and work force development. Outsourcing, insourcing, offshoring and many other hallmarks of the global economy (including the use of “adjuncts” in academia, my own corner of the world) owe no small debt to the ideas developed by the temp industry in the last half-century.American employers have generally taken the low road: lowering wages and cutting benefits, converting permanent employees into part-time and contingent workers, busting unions and subcontracting and outsourcing jobs. [My italics-MS]

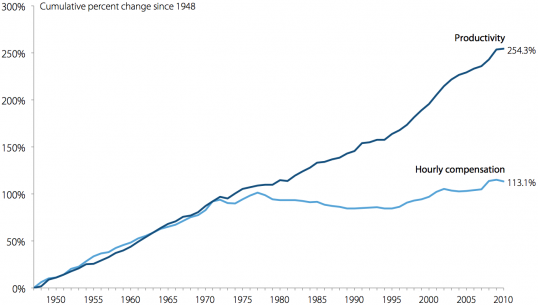

But while wages and benefits have been cut, employee productivity has gone up. So where has the money generated by increased productivity gone? As pointed out by economist Lawrence Mishel, president of the Economics Policy Institute:

Income inequality has grown over the last 30 years or more driven by three dynamics: rising inequality of labor income (wages and compensation), rising inequality of capital income, and an increasing share of income going to capital income rather than labor income. [My italics-MS]

…

A key to understanding this growth of income inequality—and the disappointing increases in workers’ wages and compensation and middle-class incomes—is understanding the divergence of pay and productivity. Productivity growth has risen substantially over the last few decades but the hourly compensation of the typical worker has seen much more modest growth, especially in the last 10 years or so.

…

However, the experience of the vast majority of workers in recent decades has been that productivity growth actually provides only the potential for rising living standards: Recent history, especially since 2000, has shown that wages and compensation for the typical worker and income growth for the typical family have lagged tremendously behind the nation’s fast productivity growth.

As this graph shows, the divergence began around 1973, which roughly coincides with the explosive growth in wealth of the oligarchs.

Mishel suggests what needs to be done.

Reestablishing the link between productivity and pay of the typical worker is an essential component of any effort to provide shared prosperity and, in fact, may be necessary for obtaining robust growth without relying on asset bubbles and increased household debt. It is hard to see how reestablishing a link between productivity and pay can occur without restoring decent and improved labor standards, restoring the minimum wage to a level corresponding to half the average wage (as it was in the late 1960s), and making real the ability of workers to obtain and practice collective bargaining.

This is why increasing the minimum wage is a good idea. The proposal by president Obama of boosting it by two stages from the current $7.25 an hour to $9 by 2015 and then indexing it to inflation is good but not enough. It should be $10.59 if it is to regain the purchasing power it had in 1968. This is not the solution to many of the problems that the poor and working class face, but it helps.

It’s sad that we have to lobby for policies which make us as good as we were in 1968.

So, that gnawing feeling of my life wasting away as I sit in a cubicle pissing on my engineering degree isn’t a figment of my imagination?

I’m not sure what’s more frightening… the global warming hockey stick graph, or that one…

(There is something weirdly disturbing about the image of a woman with a pencil in her mouth, like a horse with a bit between its teeth.)

Sexy.

I think the picture was meant to be sexy.

Bondage. Sadism. That sort of thing. (Fits in pretty well with the oligarchic worldview, no?)

The add is pretty disturbing and dehumanizing -- it’s basically saying that a “Kelly Girl” has no human needs,no health problems, no desires, and that the great thing about a ‘Kelly Girl’ is you can toss out the ‘Kelly Girl’ whenever you feel like. It plays into the desires of the ruling class of treating the rest of the population as disposable rubbish.

I think the picture was meant to be sexy.

Yeah, the subtext is “never says ‘no'” -- a perfect wage-slave with sexual overtones implying a perfect sex-slave too.

The stimulus plan last year gave everyone a little bit more each pay check -- it’s also credited with propping up GDP by a point or so. Image now that everyone gets a pay check boost of 40-100%. What would that do to the economy? That’s roughly the impact of decoupling wages from productivity.

The other option for all that wealth is you could give it to the richest 400 families in the country (who were already, well, richest).

Notice that there isn’t any question about ‘paying’ for this, we’re talking about systemic allocation of wealth that was generated.

Economy, how does that fkng wrk?

The last paragraph was the one that got me. “Never fails to please. If [she] doesn’t work out, you don’t pay -- we’re that sure of our girls.” Doesn’t quite sound like they’re advertising clerical temps!