Observational or experimental data, if plotted on a graph, consist of a set of discrete points. There are potentially an infinite number of lines that can be drawn through those points. In some cases, the data itself suggests an overall rising or lowering trend but whether the relationship is a simple linear one or more complicated is not often easily discernible with the naked eye. We have to impose a curve based on prior expectations of what might be happening based on our intuition or on a theoretical model.

If you are given a set of data points that look suggestive of a straight line, you can draw the line that best fits those points by mathematical methods known as linear regression of which there are a few varieties.. The ‘quality of fit’ to the straight line (i.e., whether the points lie close to the straight line or are widely scattered about it) is also obtained by this process.

So what data should one include in an analysis? Scrupulous scientists tend to include all the data within a given range in the analysis, unless there are good reasons as to why some data had to be excluded. This sometimes occurs with so-called ‘outliers’, where one or two data points lie far away from the general trend while the rest lie close to the best-fit line. The goal of science is not to be mathematically rigorous for its own sake but to arrive at useful conclusions. Hence in dealing with outliers, one has to judge whether they might have occurred due to errors that make them invalid and as a consequence are leading the investigator in the wrong direction. It is a tricky call. The ethically preferred choice in such situations is usually to provide all the data and clearly explain why a few were excluded from the analysis. By providing all the data, other scientists can decide whether that action was warranted or whether the omitted data reflect an underlying problem with the conclusion.

The choice of the range of data is even trickier. For example, in analyzing economic trends or the stock market, should one go all the way back to the very beginning when records started to be kept? That may not yield useful results in some cases. So which range should one use?

While the default position is that one should use all the data that are available and relevant unless one has good reason to exclude some, in scientific experiments the range is usually determined by the nature of the hypothesis being tested or the limits of the equipment or because of more prosaic reasons like limits of time or money. In the case of limits of the equipment, one should treat the data at the two end points with greater skepticism simply because they are at the limits and thus may not be as reliable as the rest, and one can make the case for their exclusion.

What should never be done is to cherry pick data to arrive at a predetermined conclusion. But with politically charged issues, there is often the temptation to adjust the range of the data in order to achieve a predetermined conclusion. By using a carefully selected baseline, one can enhance or reduce an effect.

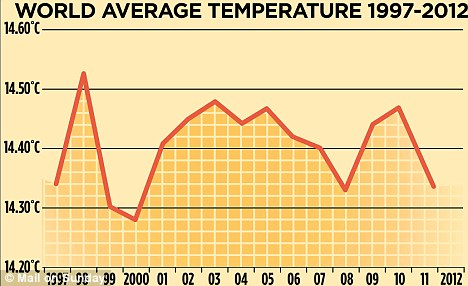

The London Daily Mail recently reported that “The supposed ‘consensus’ on man-made global warming is facing an inconvenient challenge after the release of new temperature data showing the planet has not warmed for the past 15 years.” They released a graph of average temperatures in support of their conclusion.

This news was eagerly embraced by global warming deniers and relayed in the US by the Washington Times.

Is it really true that global warming has plateaued? Let’s see how this conclusion was arrived at. As Kevin Drum shows, by limiting the range of average temperatures versus year to the time period 1997-2011 and doing a linear regression on that limited set of data, people were able to claim that global warming had stopped, because the best-fit straight line was almost horizontal. This is because 1997 was an unusually warm year while 2011 was colder than average, thus using 1997 as the baseline gave the deniers the conclusion they were seeking. However, Drum shows that if you take 1961 as the baseline and plot the data for the period 1961-2011, then the best-fit straight line is rising, suggesting that there has been no let up in the warming trends.

But it is not an unreasonable question to ask if the warming trends have changed in recent years and so using a more limited set of data over a shorter time scale is not, in principle, a wrong thing to do. What is wrong is to make the choice with the conclusion in mind, putting one’s thumb on the scale, so to speak. I do not know if that was the case here or whether the 1997-2011 period was arrived at for bona fide reasons. This is why history is important. If the scientists have a reputation for ethical practice or there has been a systematic practice of choosing 15-year periods for measurement of these trends and the recent one was just the latest in that series, then it would be acceptable. If this was a one-off study by people with a vested interest in the outcome, then the fact that 1997 just so happened to swing the conclusion one way makes it suspicious.

When I read the title, I had to chuckle because this has been an unusually warm winter in my area this year, with no real signs becoming particularly wintery anytime soon. Not relevant to the statistics, but funny none-the-less.

I wonder how many data points Daily Mail put into a spreadsheet over and over again until they found this nice ideal range to “report” on?

I always thought any graph of global climate change should start a few hundred years before the Medieval Warm Period. That seems like a reasonable starting point.

In 1999, a climatologist friend told me “Looking at both the scatter and the trend, we can predict that 1998 is unlikely to be exceeded in the next ten years, and that the deniers will turn round and say ‘Look, the warming has stopped’.”

The second prediction was spot on. The first -- well, by most measures, 2010 was hotter than 1998.

Global warming has not tapered off, because its called climate change now. And the climate never stops changing.

Re Paul Braterman @ #3

Actually, there were several years in the interval 2001 -- 2010 that were as warm or warmer the 1998. 1998 was an outlier that was caused by an unusually strong El Nino condition. If 1998 is excluded as an outlier, then there has been significant warming over the last 20 years.

Your anecdote is actually irrelevant. This post is about climate change. Your comment is about the weather.

Except that the important thing about climate change is that it is anthropogenic. AGW started with the industrial revolution, not the MWP

This is because both the ENSO and solar cycles peaked around 1998 and have been falling off ever since.

Because of what statisticians call “noise”, it is foolhardy to look at global warming trends over less than about a 30 year interval. When you do look at 30 year intervals, the trend has always been up since the industrial revolution, except for an initial negative effect from industrial pollution which increased the levels of particluate matter in the atmosphere.

In the top graph, 1997 and 2011 are almost exactly the same, while in the lower graph, while the overall shape is similar over this period, 2011 is clearly higher than 1997. What gives?