Ken Ham is preaching about what science is again. He’s accusing the secular activist Zack Kopplin of being “brainwashed” by evolutionist propaganda, and to support this claim, he once again drags out the tired proposition that there are two kinds of science, historical and observational, and that only the observational kind is valid; well, unless the historical version is based on the Bible, which in his dogma is an unassailable compendium of absolutely true facts about the past.

What’s more, Kopplin—like almost all evolutionists—confuses historical science with operational (observational) science. Operational science is indeed observable, testable, falsifiable, and so on—but none of those words describes evolutionary ideas! While biblical creation may not be provable through tests and observation, neither is molecules-to-man evolution (or astronomical evolution). And in fact, the evidence that is available to us concerning our origins makes sense in the biblical creation-based worldview, not the evolutionary one. Of course, secularists mock creationists for separating out historical science and operational science. But they do that because the secularists want the word science to apply to both historical and operational science so that they can brainwash people (like Kopplin) into thinking that to believe in creation is to reject science.

This is utter nonsense. It’s a phony distinction he makes so that he can bray, “Were you there?” at people and pretend that he has refuted anything they might say about the past. It is a set of appalling lies from a know-nothing hidebound fundamentalist who knows nothing about science, and who happily distorts it to contrive support for his ridiculous beliefs.

It is false because of course I can observe the past. The present is the product of the past; if I open my eyes and look around me, I can see the pieces of history everywhere.

I live in the American midwest. I can go into my backyard and see on the surface the world as it is now; fenced and flattened, seeded with short grasses, surrounded by paved roads and houses. But it takes only a little effort to observe the past.

In ditches and pioneer cemeteries and dry unplowable ridges, traces of an older world, the prairie, still persist. I can find clumps of tallgrass, scattered forbs, rivers fringed with cattails, turtles like primeval tanks on the banks, frogs and salamanders lurking in tangled undergrowth, fragmented bits of the pre-European settlement. I can see relics of a changing human presence; there are places where flint arrowheads turn up regularly, and to the south are the native pipestone quarries. I can walk along the increasingly neglected railroads, and trace how they contributed to our presence here; small towns sprinkled along the railroad right-of-way, acting as central depots for tributaries of wagons on dirt roads, hauling corn to the granaries. It’s all here if you just look; it’s not a story told by fiat, poured into books that we accept as gospel. That history lies in scars in the land, observable, testable, falsifiable.

I can dig into the ground with a spade and see the rich dark loam of this country — the product of ten thousand years of prairie grasses building dense root systems, prairie dogs tunneling through it, the bison wallowing and foraging. This isn’t an illusion, it’s the observable result of millennia of prairie ecosystems thriving here, and it’s the source of the agricultural prosperity of the region. I can sieve through the muck that has accumulated in prairie lakes, and find pollen from the exuberant flora that grew here: clover and grasses, wildflowers and the flowering of the wetlands. I can track back and see the eras when the great eastern deciduous forests marched westward, and when they staggered back. It’s all in the record. It all contributed to what we have now.

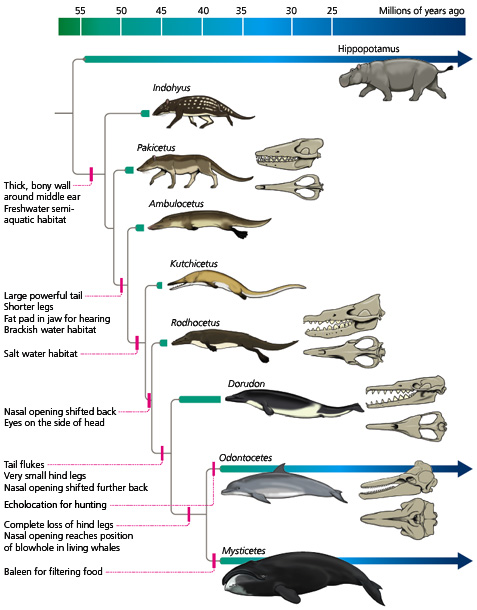

We can go back and back. We can see the scattered rocky debris left as the glaciers retreated; we can see the vast depressions left by the pressure of ancient lakes; we can see the scouring of the land from their earlier advance. Seeing the landscape with the eyes of a geologist exposes its history. While the glaciers demolished the surface, we can also find places where seismic cataclysms thrust deeper layers to the surface, and there we find that millions of years ago, my home was the bottom of a huge inland sea, that diatoms silted down over long ages, burying the bones of plesiosaurs and nautiloids in chalky deposits.

Again, this is not mere historical assertion (and isn’t it demeaning to treat history as something empty of evidence, too?). Open your eyes! It’s all written in towers of stone and immense fractures in the earth, in microscopic drifts of long dead organisms and the ticking clock of radioactive molecules. We are immersed in the observable evidence of our past. Everything is the way it is because of how it got that way — you cannot blithely separate what is from the process that made it.

I can see it in me, too — biology is just as much a product of the changing past as is geology and ecology. I can look in the mirror and see my mother’s eyes and my father’s chin; I can observe myself and see my father’s sense of humor and my mother’s bookishness. I remember my grandparents and my great-grandparents, and looking back at me are a collection of familial traits, all shuffled and juggled and reconstituted in me.

Beyond those superficial impressions, I can have my genome analyzed and find my particular pattern of genes shared in distant places in the world. I know that my family came from Northern Europe, that in turn they migrated out of central Asia, that before that they were living in the Middle East, and long before that, a hundred thousand years ago, they were an adventurous (or desperate) tribe of people moving northward through East Africa. This is not a mere story, a fairy tale invented by ignorant scribes — my ancestors left a trail of alleles as they wandered over three continents, a trail we can follow even now.

“Were you there?” Yes. Yes, I am here, imbedded in this grand stream of history, aware of my place in it, seeing with open eyes the evidence that surrounds me. And I pity those unable to see the grand arena they are a small part of, who want to deny that history is observable.