We’ve had a very wet summer so far here in the upper Midwest — the potholes are full of water, our backyard is sodden, the plants are thriving, but that also means that this plague is drifting in vast clouds everywhere.

The horror. The horror.

The debate about intelligent, extra-terrestrial aliens goes on, with the usual divide: astronomers insisting that the galaxy must be swarming with alien intelligences, which is popular with the media, and the biologists saying no, it’s not likely, there are probably swarms of single-celled organisms, but big multicellular intelligences like ours are probably rare. And the media ignores us, because that answer simply is not sufficiently sensational.

But we will fight back! Here’s an interesting review of the alien argument. There is actually a historical and conceptual reason why astronomers think the way they do.

In response [to a paper arguing that SETI was a waste of time], Sagan co-wrote a paper with William Newman “The Solipsist Approach to Extraterrestrial Intelligence” which right from the title attacks Tipler for believing Earth to be unique. Sagan is of course citing the Copernican Principle, which roughly states the Earth is NOT the center of the heavens. The Copernican Principle is the modern foundation for Astronomy, Cosmology and Relativistic Physics. Sagan thought anyone claiming the Earth to be special must be doing bad science. Here’s a typical quote: Despite the utter mediocrity of our position in space and time, it is occasionally asserted, with no sense of irony, that our intelligence and technology are unparalleled in the history of the cosmos. It seems to us more likely that this is merely the latest in the long series of anthropocentric and self-congratulatory pronouncements on scientific issues that dates back to well before the time of Claudius Ptolemy.

It’s all about our perception of the rules. Astronomers see a universe with uniform laws that set up similar patterns everywhere: stars, rocks, gas. Life is lumped in with rocks as a phenomenon that just pops up everywhere, and with their limited idea of biology, just see all life as life like ours. Biologists also see universal laws, but we know from our experience that those laws generate endless diversity — there are millions of species on this planet, and each one is unique.

Now unlike Astronomy, the discipline of Biology takes a highly favorable view of uniqueness. Evolution constantly discovers quirky and highly contingent historical paths. Biology takes it for granted that everybody is a special snowflake. In fact the third sentence of Tipler’s 1980 paper calls this out:

The contemporary advocates for the existence of such [extraterrestrial intelligent] beings seem to be primarily astronomers and physicists, such as Sagan (2), Drake (3), and Morrison (4), while most leading experts in evolutionary biology, such as Dobzhansky (5), Simpson (6) Francois (7), Ayala et al. (8) and Mayr (9) contend that the Earth is probably unique in harbouring intelligence, at least amongst the planets of our Galaxy.

And as quoted in Mark A. Sheirdan’s book, we have eminent Evolutionary Biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky (“Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution“) joining the fray:

In his article Dobzhanksy turned Sagan’s argument on its head. Dobzhansky cited the fact that of the more than two million species living on Earth only one had evolved language, extragenetically transmitted culture, and awareness of self and death, as proof that it is “fatuous” to hold “the opinion that if life exists anywhere else it must eventually give rise to rational beings.”

And here’s a nice, short table to summarize the differences.

I have to add that it is probably another of those universal laws that Darwinian replicators will expand to fill an empty ecosystem, but that there are many ways to do that. It’s also a rule that the replicators are exploiting short term advantages to supplant competitors — there is no teleological imperative that says Strategy X is a good one, because while it slows our species down for the next billion years, there’s a chance we might build spaceships two billion years from now. Spaceship building is never going to be a selectively advantageous feature — it’s only going to emerge as a spandrel, which might lead to a species that can occupy a novel niche. And that means that spaceship builders are only going to arise as a product of chance, which will mean they’re going to be very rare.

On the other hand, a species that does successfully exploit space as an ecosystem is going to have a phenomenally fascinating future history of radiating forms. Think of the first space colonizers as equivalent to the first cells that evolved a metabolism that allowed them to exist outside the coddled, energy-rich environment of a deep-sea vent. It’s only the first step in a long evolutionary process that’s going to produce endless forms most beautiful…and also unexpected variations. It’s silly to expect that the successful, thriving interstellar life forms will be bipeds adapted to life on a planetary surface, living in large metal shells as autonomous agents crewing a spaceship. The real thing would be alien, and probably terrifyingly incomprehensible.

The zombie plague was a dud. When the first cases emerged, scattered around the globe, everyone knew exactly how to put them down: destroy the brain. The world had been so saturated with zombie comic books, zombie TV shows, zombie novels, and zombie movies in the greatest, if unplanned, public health information program ever, that the responses to the outbreaks was always swift and thorough. In fact, most civilian casualties were caused not by the zombies themselves, but by the way everyone had been conditioned by the media to respond to lumbering, moaning, disheveled humanoid forms with instant and brutal violence.

The death of a few homeless or mentally ill people, or others who just weren’t perky morning people, was considered a small price to pay for the ruthless efficiency with which the zombie problem was eradicated. There was talk of giving George Romero a Nobel peace prize; Time Magazine ran an issue with “Heroic Humanity” featured on the cover; the public acquired a cocky attitude and brain-smashing weapons of destruction became the hot new fashion accessory. The horror of the worst catastrophe we could imagine, the emergence of an evil twin of our species, corrupt and mindlessly destructive, had been met and dismissed with arrogant ease.

An important lesson was not learned. Zombies were our mirror image, big animals that were short-sighted and heedlessly destructive, and we had easily wiped them out…because big animals are delicate, fragile things with a limited population size, requiring immense amounts of cooperation to survive. Our pride was undeserved. We had discovered how easy it was to kill small groups of bipedal primates. Nature laughed at our trivial accomplishment.

The same plague had been burning through rat populations. Every city, every small town garbage dump, every ship, had been boiling with upheaval in the darkness as the zombie rats spread the infection everywhere. The rats were numerous, and it took three months for the disease to consume them…and then the undead rodents slithered upwards, looking for a new food source. They were ubiquitous and silent and sneaky, and found ways into bedrooms at night, where the smug humans lay with shotguns and pistols and hammers for demolishing large-skulled stupid targets, their doors safely (they thought) barred against 70 kilogram intruders. The little, mindless zombie rats scurried forward, and gnawed.

Homo sapiens was extinct within a year.

(I had this idea for a great and accurate zombie novel that would reveal the true message of the zombie fad — come on, look at yourselves, it’s all about rapacious humans with no restraint — and would also make me millions of dollars. I got up this morning all excited and rushed to start writing it, and then I discovered that I could tell the whole story in five paragraphs. Oops. Is there much of a market for one-page novels? With a totally depressing conclusion?)

It’s been cephalopod week, and on Science Friday, they featured our old friend, the vampire squid.

Stinky stuff! This fits perfectly with my biased preconceptions. So here are two examples of chemistry used to analyze things you’d normally run away from.

The oldest traces of human poop have been dug out of a cave in Spain — and it’s Neandertal poop. It’s about 50,000 years old, and it’s been reduced to a compressed, thin smear of organic compounds, so I guess it isn’t actually so stinky anymore, but there was enough of it to analyze chromatographically. In case you’ve wondered your whole life about what Neandertal poop would look like, here you go.

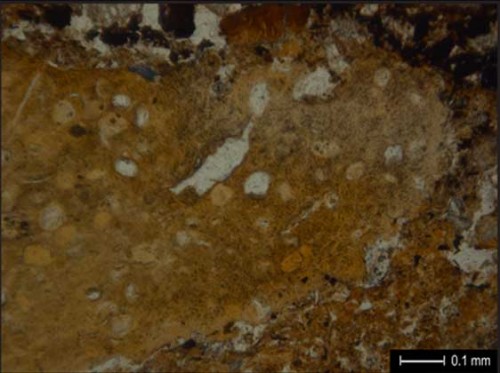

Microphotographs of a slightly burned coprolite of putative human origin identified in El Salt Stratigraphic Unit X (sample SALT-08-13). The images under plane polarized light show the pale brown color and massive structure of the coprolite, as well as the common presence of inclusions, which are possibly parasitic nematode eggs or spores.

Dead for 50 millennia, and what we know about this dead person is that they took a massive dump that was full of parasites. TMI.

I thought the paper was preliminary and rather general — they don’t or can’t make very specific conclusions, but then, I imagine they were excited to be the first to get any discussion of Neandertal feces into the scientific literature. We do know a couple of things: Neandertals ate both their meat and their vegetables, and they had gut bacteria with similar physiological properties to our own.

Taken together, these data suggest that the Neanderthals from El Salt consumed both meat and vegetables, in agreement with recent hypotheses based on indirect evidence. Future studies in Middle Palaeolithic sites using the faecal biomarker approach will help clarify the nature, role and proportion of the plant component in the Neanderthal diet, and allow us to assess whether our results reflect occasional consumption or can be representative of their staple diet. Also, this data represents the oldest positive identification of human faecal matter, in a molecular level, using organic geochemical methods.

Besides having corroborated our method and obtained the first evidence of an omnivorous Neanderthal diet from faeces, our results also have implications regarding digestive systems and gut microbiota evolution. Approaching the evolution of the human digestive system is difficult because there is no fossil record indicating soft tissue preservation. Our results show that Neanderthals, like anatomically modern humans, have a high rate of conversion of cholesterol to coprostanol due to the presence of bacteria capable of doing so in their guts. Further research will allow us explore this issue in the context of human evolution.

I said I had two unpleasant examples of useful chemistry, and here’s the second: using the characteristic odors of different stages of decay to quantify the time of death.

An international research team used two-dimensional gas chromatography time-of-flight mass spectrometry to characterise the odours that create this smell of death: volatile organic compounds (VOCs). By measuring the VOCs released from pig carcasses the team identified a cocktail of several different families of molecules, including carboxylic acids, aromatics, sulfurs, alcohols, nitro compounds, as well as aldehydes and ketones. The combination and quantities of these VOCs change as a function of time as a cadaver goes through different stages of decomposition.

I think I’m getting a sense of the difference between chemistry and biology. I prefer the bodily fluids in my subjects to be fresh, preferably spurting; chemists seem to favor observing the degradation and volatilization of fluids from dead things. Chemists may offer their repudiations of my sentiments in the comments.

I think that’s the only reasonable response. We’ve been conditioned to think that animals are all furry and big-eyed and most importantly, cute, and every animal that isn’t must be reclassified as vermin. We’re going to need a radical readjustment of the public; every time you send someone a LOLcat, a thousand annelids and a million arthropods die in despair.

At least, that’s how I feel on the news that the Smithsonian is closing their Invertebrate Zoo. There are some fucked-up priorities here.

The Smithsonian says the Invertebrate Exhibit costs $1 million a year to operate, and that necessary upgrades to the facility will cost another $5 million. "We have several other fundraising priorities which preclude us from launching a… campaign for the invertebrates to stay in their existing space," reads a statement on the Zoo’s Facebook page.

The National Zoo’s annual budget runs about $20 million, with its friends group kicking in another $4 to $8 million a year. Which basically means the Zoo has decided it can’t afford to allocate five percent of its annual budget to educate the public about 97 percent of the animal species in the world.

“Priorities”. What defines their priorities? An accurate presentation of the science, or pandering to brains high on fluff? I suggest we start feeding the Red Pandas to the octopuses until those priorities get readjusted.

This one isn’t about the picture; go listen to the singing of the bats.

Sean Carroll criticizes those physicists who say silly things about philosophy, answering three common, and erroneous, complaints from the ‘philosophy is dead!’ mob. It’s pretty good, and I was thinking that maybe this would finally sink in, but then I read the comments. Oh, boy.

My favorite was the guy who said philosophy is pointless and that there’s nothing that a philosopher can do that a good physicist cannot.

If you ever wonder why physicists have a reputation for arrogance, there it is: do they really believe that the 4+ years of graduate work required to get a Ph.D. in philosophy involves doing nothing? That has to be the case. I took a look at the degree requirements for several doctoral programs in physics: Houston, Tulsa, Stanford, and NYU (just the ones that came up first in a google search). Despite the word “philosophy” in the title “Doctor of Philosophy”, none of them require any coursework in philosophy. Not one bit.

Physics isn’t the only discipline with this flaw, though; it isn’t a requirement in any biology program that I know of, and though I’ve tried to squeeze a little bit into our undergrad biology program, there’s considerable resistance to it. In general, science programs aren’t very good at giving any introduction to philosophy — so it’s always amusing to see graduates of these programs lecturing, from their enlightened perspective, on the uselessness of this discipline they know next to nothing about.

I feel the same annoyance at this know-nothing attitude that I feel towards all those people who claim to know everything important about evolution — it’s so easy, they’ve mastered it with a little casual reading on the side. And then I mention a big something like drift or founder effect, or some fascinating little thing like meiotic drive, and they’re completely stumped. Didn’t know that before. But they know all about evolution, yes sir!

Some of them are physicists, too.

This is an excellent piece on that quack, Dr Oz, by John Oliver. The first 5 minutes is spent mocking the fraud, but then, the last ten minutes are all about the real problem: the evisceration of the FDA’s regulatory power over supplements, thanks to Senators Hatch and Harkin.

OK, there is a silly bit at the end where they show that you can pander to your audience without lying to them about the health benefits of magic beans, but still — let’s beef up the FDA, all right?