At the beginning of the term, I was constantly repeating the mantra, “your data is your data” to the students — they came in expecting that science experiments had a foreordained conclusion, like a recipe that you followed and at the end you got cake. If there was no cake it’s a failure! That’s not true, though, that even if it doesn’t end up as you expected, it was still data. Unexpected data just takes more work to interpret (they don’t like that part) or that you need to do more experiments to puzzle out how it happened (they like that even less).

I’m grading lab reports now, and can say that they seem to have figured it out. They’ve stopped judging their results and are instead asking questions and analyzing, which is all I really want.

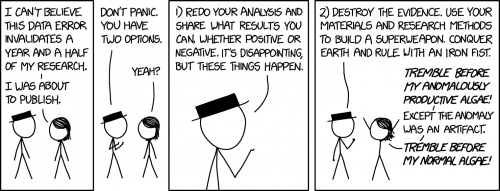

This would have been a good comic to include in their training early on, though.

That’s more or less how I was taught science in middle and high school. The lab experiments were all suppose to be a hands-on-demonstration of some established principle of science–like how temperature affects a chemical reaction or how lens affect a beam of light. You know, basic stuff. You do steps A-through-B and you got the expected result. If something went wrong, you didn’t follow the directions. F-minus for you!

I suppose that sort of “lab work” is fine for teaching the basics, but I imagine that it doesn’t really prepare you for REAL laboratory work where you are trying to test an actual hypothesis of you’re own.

I had science classes where you were graded off if you didn’t get the “correct” answers, too. I could always understand the concepts that we were being taught, so the only thing I learned in all of those “labs” was that I was bad at science.

Good grief do I relate to this! Physics major with five years of grad school and two MS degrees. All of the labs I did or taught had a definite answer. Get to the real world, not necessarily true. My favorite was hey, this material is known to be outside of the main range of the test: run it anyway, it is the best we got.

Edit @ 1

…an actual hypothesis of your own.

“you need to do more experiments to puzzle out how it happened (they like that even less).”

I would have like it at high school, but couldn’t do it because I had run out of time. Exactly when my data weren’t what I had expected I could figure out what I had done wrong and what I should have done better. So when I became a teacher myself I never was harsh on pupils who found themselves in that situation.

I’d say yes and no. Some labs are designed to get specific answers while others are a bit more open-ended. Given my relationship with the gods of chemistry and physics, it drove my chem prof bonkers.

First lab is the classic experiment that is more about teaching you how to take notes in chem lab than actually the chemistry you’re doing: First day of lab, you are given five different chemicals, each defined. You are to take each possible pair, mix them, notice the reaction that occurs, if any (color change, precipitate, odor, etc.) and write it in your lab book. Second day of lab, you’re given the five chemicals, none labeled. By mixing the chemicals together and consulting your notes from the previous day, you are asked to identify which is which.

So it’s the second day and I’m in the middle of the experiment. The professor comes and glances at my notebook, sees that I have nothing written down for the second day, and asks me why I’m not doing the experiment. “I am. Nothing’s reacting. It wasn’t very nice of you to give us diluted solutions. It’s been very hard to get any results.” His face screws up in puzzlement and he says that no, everything is the same as before. He takes two test tubes, cleans them, gets some of Chemical X and some of Chemical Y, mix, shake-shake-shake, all this lovely precipitate starts falling out of solution He asks me to show him how I’m doing it. So I take two test tubes, clean them to ensure no residue, get some of Chemical X, some of Chemical Y, mix, shake-shake-shake, and show him the completely clear solution: “See? Nothing.” We do this with two others…he cleans the tubes, mixes, shakes, color change. I take the same tubes, clean them, mix, shakes, nothing.

He is completely baffled and tells me to look at other student’s results in order to get my notebook together because the lab will be ending soon.

Next new lab is an experiment to make alum. We are all asked to bring in a soda can and are given instructions on cutting a piece, cleaning it off the paint and polymer coating, and going through the long process of synthesizing alum from aluminum (dissolve the aluminum in potassium hydroxide on a hot plate, adding sulfuric acid, getting crystals, drying them with the Gooch, etc.) The goal is to weigh your alum crystals compared to the amount of aluminum you started with and, knowing the various chemical reactions that were taking place, determine your yield. It was commonly known that due to the rushed way in which the experiment would take place, you would likely have a yield of well over 100% when the expected yield would be less than half. Thus, you were to write up possible explanations as to why your yield was different.

My partner and I couldn’t get past the first step. The aluminum simply would not dissolve. Since it was being done over a hot plate, the lab assistant suggested we increase the heat…and we eventually boiled all the liquid away with the aluminum slightly blackened but no reaction. We had to get the grand high poohbah of the chemistry department (J. Arthur Campbell…some of you may know who that is from certain science films you saw in school) to try and help rescue the experiment.

Our final weigh-in would have indicated a yield of over 600%, but we were pretty sure part of that was that our crystals were still sopping wet and we weren’t even sure that what we had truly was alum. Made for an interesting write-up.

There is a point to teaching labs where the expected outcome is very well-defined. It teaches not only the actual science but also teaches protocol for how to do science. Once you get those basics, you can start improvising.

I had the opposite experience. In high school I was involved in several experiments where the outcome was not preordained and particularly with the synthesis of aspirin, our lab group screwed it up several times, learning each time how to do it better until we made aspirin.

Then at uni, for pracs we were given an experimental design, given a set of tools and instruments, and told what to do. There was a pretense at not telling us what the desired outcome was, but since we would be marked down for not getting the ‘right’ result, and since the experimental design plus background knowledge made it obvious what we should be looking for, it was little more than a test of our ability to follow instructions with tacit encouragement to fudge results.

rrhain–

You’re not by any chance related to Wolfgang Pauli?