The crackpots are bustin’ out all over — not just in politics, but also in science. Remember Stuart Pivar? The septic tank tycoon who invented a whole new theory of evolution and development that he called Lifecode, built entirely around imaginary drawings of how embryos formed by folding and stretching themselves like balloon animals? It was total nonsense. There was no data. Much of his imagined topological transformations contradicted known embryological patterns, and he’d clearly never looked at real embryos. It was loosely based on structuralism, like the work of D’Arcy Thompson, which I consider useful and interesting, but it ignored all the work of the last century on induction and cell signaling and gene regulation. Trust me on this, no modern renovation of evo-devo will be able to just wave away gene and molecular interactions shaped by genetic variation as irrelevant, but that’s what Pivar has done.

I should also disclose that Pivar filed a lawsuit for $15 million against me in 2007, which he dropped as it threatened to become big news. Dang. What is it with people wanting millions of dollars from me?

Anyway, Pivar has a new publication! In the Elsevier journal Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology! With new coauthors!

The first author is David Edelman, an anthropologist turned neuroscientist now employed as an adjunct professor of psychology at UCSD. He has no expertise in either evolution or development, but he does know the crackpot buzzwords: he endorses a “paradigm shift” in evolutionary theory in an interview with Susan Mazur on the Huffington Post. I don’t encourage you to read that article, unless you have a high tolerance for ideas like “we’re living in a hologram”, “complexity is a product of viral infections”, and “the constructal law of flow systems” thrown around as meaningful, with mentions of “epigenetics!”, another deeply abused concept by the crackpots.

The second author is Mark McMenamin. He’s the guy who claimed that piles of ichthyosaur vertebrae were evidence of a Triassic kraken, a giant predator that he had no evidence for other than his claim that the bones he found were artistically arranged. He also endorsed Pivar’s LifeCode.

The third author is Peter Sheesley. He’s not a scientist, he’s an artist. But of course he is! Once again, Stuart Pivar is going to rely on artistic imaginings to make his case, rather than, you know, data and evidence, so naturally he needed to bring in someone with some talent at inventing images.

The fourth and final author is Pivar himself, since this was all done in his “lab”.

The paper is titled “Origin of the vertebrate body plan via mechanically biased conservation of regular geometrical patterns in the structure of the blastula“. Here’s the abstract.

We present a plausible account of the origin of the archetypal vertebrate bauplan. We offer a theoretical reconstruction of the geometrically regular structure of the blastula resulting from the sequential subdivision of the egg, followed by mechanical deformations of the blastula in subsequent stages of gastrulation. We suggest that the formation of the vertebrate bauplan during development, as well as fixation of its variants over the course of evolution, have been constrained and guided by global mechanical biases. Arguably, the role of such biases in directing morphology—though all but neglected in previous accounts of both development and macroevolution—is critical to any substantive explanation for the origin of the archetypal vertebrate bauplan. We surmise that the blastula inherently preserves the underlying geometry of the cuboidal array of eight cells produced by the first three cleavages that ultimately define the medial-lateral, dorsal-ventral, and anterior-posterior axes of the future body plan. Through graphical depictions, we demonstrate the formation of principal structures of the vertebrate body via mechanical deformation of predictable geometrical patterns during gastrulation. The descriptive rigor of our model is supported through comparisons with previous characterizations of the embryonic and adult vertebrate bauplane. Though speculative, the model addresses the poignant absence in the literature of any plausible account of the origin of vertebrate morphology. A robust solution to the problem of morphogenesis—currently an elusive goal—will only emerge from consideration of both top-down (e.g., the mechanical constraints and geometric properties considered here) and bottom-up (e.g., molecular and mechano-chemical) influences.

I highlighted a few words and phrases I found risible. Please note: this abstract is full of tells that would let any reasonable reviewer instantly sense that it was a garbage paper, free of data and full of wild surmise. I also have to point out a phrase that told me instantly that, once again, none of the authors have bothered to look at any real embryos: underlying geometry of the cuboidal array of eight cells produced by the first three cleavages

. This makes no sense. In what organism? The first 3 division of a zebrafish embryo produce 8 cells forming a monolayer sheet on top of the massive yolk sac. Mammalian embryos after the third division will throw away that geometry and segregate off a big chunk of the organism to form the blastocyst wall and, eventually, the placenta. There is a huge amount of variation between vertebrate embryos as blastulae and diversity in the gastrula stage which subsequently converges on a more universal pattern after the gastrula stage — Pivar is trying to claim a universality stemming from the 8 cell stage on the basis of morphology. That is frankly unbelievable. He is not only making stuff up, he’s building his whole model on an imaginary ideal pattern of early cell divisions that does not exist.

The paper itself is more of this irresponsible dishonesty and ignorance.

Gastrulation is characterized by a phase in which massive cell proliferation induces the ball of cells of the blastula to begin collapsing inward at its lower pole to form a two-layered, vase-shaped form. This form is preserved in radial animals (Fig. 1).

NO IT ISN’T. Where does he get this bullshit? Gastrulation is a process that varies in different vertebrates; in frogs and fish it involves the inward migration of cells at the blastopore, which is not at the poles (by which I’m assuming he’s refering to the animal/vegetal axis, but who knows what the hell he’s talking about), and neither frogs or fish ever look “vase shaped”. In birds and mammals you get invagination in the middle of a flat sheet of cells, along the primitive streak. They look even less “vase-like”.

You, like me, might be wondering where this bizarre notion of gastrulation morphology comes from. The answer is right in front of us: Fig. 1. It turns out that figure 1 is not simply an illustration of an observation, it is the observation in and of itself. There is no need to trouble yourself with looking at messy, slimy, tiny embryos when you’ve got an artist at hand who will just draw what you want to see.

And here it is, Figure 1!

Blastulation, gastrulation, and embryonic fate map. a. Egg; b–f. Cleavage; g-h. Gastrulation; i. Schematic ‘fate map’ showing orientation of prospective embryonic structures that emerge following gastrulation. aa–cc. Schematic organization of cell layers during early stages of development. aa. Blastula; bb. Blastocoel; cc. Gastrula.

Nope, sorry, I’ve never seen a vertebrate gastrula that looks anything like that. Maybe, at a stretch, you could relate it to an echinoderm gastrula, but then I dare you to find a cranium, forelimbs, and ribs in a starfish. I’m not even going to touch the amount of implied preformation in his imaginary “fate map”.

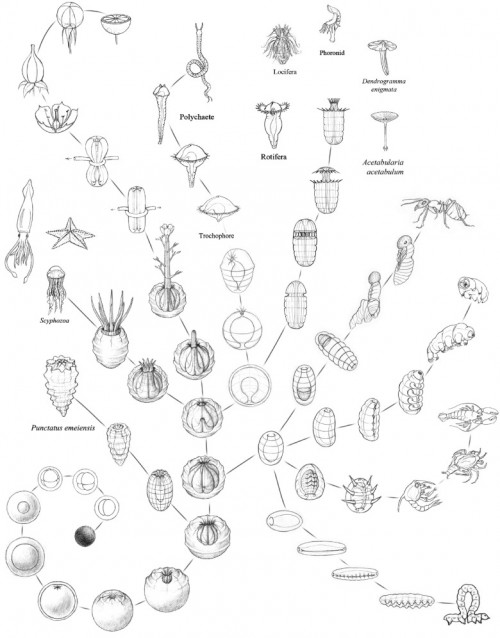

Are you ready for Figure 2? NO! You will never be ready for Figure 2. Here it is anyway, and it shows the evolution of all forms.

Schematic origin of radial and bilateral forms. The origin of phyletic diversity. Separate segments of cell layers meet at the opposite interior pole, where they join to emerge upward and out through the blastopore as tentacles (or, in the case of plants, a cylindrical shoot that opens in circlets of leaves or flowers.

This is all entirely fanciful, not based on observations of real animals at all. Oh, did I say animals? Acetabularia is a single-celled algae. It doesn’t have cell layers or a blastopore or gastrulation.

Look at about 11 o’clock on the diagram. It’s a plant, making a flower. Plants have cell walls. Their cells don’t generally migrate or move at all, and they don’t have a process called gastrulation. I just…I just…I don’t know what to say. This is madness.

Why is there a starfish just floating between the squid and the orange tree? WHY?

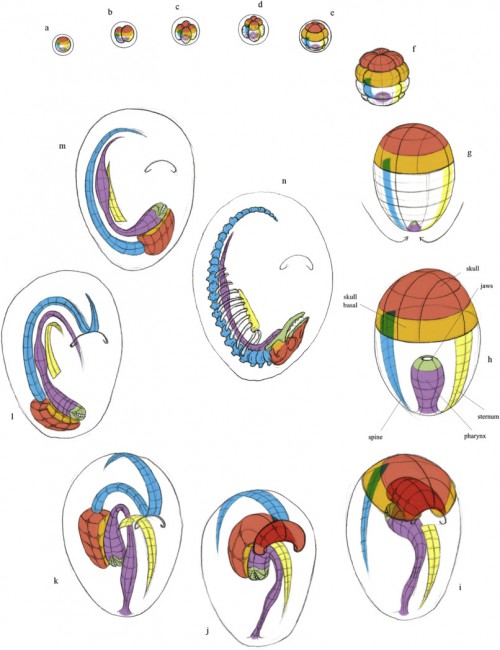

Let’s skip ahead to Figure 7, shall we? You’re really not missing anything, and it’s pretty. It just makes no sense.

Organogenesis of skull, jaws, pharynx, spine, sternum. a. Egg; b–e. Cleavage; f. Blastula; g–n. Gastrulation. The concurrent formation of the alimentary and musculo-skeletal systems is shown here.

I presume the purple stuff is invaginating endomesoderm? Why do sternum and spine rate an early mention in h? They’re later derivatives of mesoderm! I presume the blue stuff is neural plate, but where’s the inductive interaction with purple to form it? The more I stare at this monstrosity, the more I’m reduced to gibbering as I try to bring this alien mishmash into some concordance with reality. I have to simply recognize that it isn’t there.

Look, even ignoring the glaring discordance from known biology, this is useless. It has no explanatory power at all. This is “it looks like” pseudobiology: the gut looks like a worm crawling into the interior of the embryo, therefore it is explained by comparing it to a wormlike tube moving inwards. No it isn’t! What’s generating the forces? Why does this cell differentiate into one cell type, while this other cell differentiates into another cell type? Why, if morphology is sufficient to explain the organism, do we know to the contrary that molecular interactions between cells are necessary to generate the whole form? Why can we generate embryos that are different in form, along a range from subtle to radical, by small changes in genetic sequence? It answers no questions at all.

It especially fails to answer the biggest question of them all: how did this flaming turd of patent bullshit manage to pass peer review? How did the editor fail to simply throw this work in the trash where it belongs? Is everyone at Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology incompetent?

Oh. The editor of that journal is Denis Noble. He’s an idiot. I guess that explains that.

“constructal law of flow systems” is evidence of connection to yet another fringe loon, Adrian Bejan. Here’s the Wikipedia page, which seems to have been written by Bejan or a supporter.

An idiot, or just differently smart?

It would be interesting to see what his cash flow situation was and is.

PZed, minor typo in your 6th paragraph, I think:

Should be rely, no?

Also, that first paragraph of Pivar’s looks like it was written by that science paper generator from way back when that caused such a stir.

Incoming lawsuit in 3…2…1….

So, has Elsevier jumped the shark embryo yet?

Well, shit. I was just reading a couple of papers by Edelman et al on consciousness in non-human animals (i.e. how would we know?), mostly about comparative neuroanatomy. Now I have no idea whether to believe anything they said. (Anyone out there know anything about the journal Consciousness and Cognition? Or Bernard Baars? (who seems to be the editor, and also co-author of the Edelman papers. FWIW, it’s also an Elsevier journal).

looks like he’s all set to be and advisor for some sci-fi movie graphics. CGI the science!

“Why is there a starfish just floating between the squid and the orange tree? ”

Incredible String Band. 1968, I think….

So did he learn his lesson the last time? I’m hoping for no and another lawsuit to soon be coming your way, PZ. That doesn’t sound quite right, does it? It’s not as if you weren’t already living in interesting times, is it?

Fig. 2 is indeed most bizarre. i mean, they’re all bizarre, but just what exactly is Fig. 2 supposed to depict? It’s not meant to hypothesize evolution, i.e. phyletic descent. Nor, despite the li’l pre-tail of cleavage and abstracted gastrulation, could it mean to show actual patterns of embryonic development. Right? I mean, such stages are easily found as actual photographs. It’s not, I guess, supposed to be realistic at all. It’s some sort of ordered system for classifying Recurring Because Intrinsic Platonic Ideals of Form or some shit. Which, whatever, but then why the whole-cloth-imagined intermediate stages and clear developmental metaphor (if that’s what it is)?

Besides the starfish squid, too, is just floating. Apparently they are additional examples of the Jellyfish Form because…radialish tentacles/arms?? Homology seems irrelevant. And then, yeah, the flower, forming from a vegetative shoot that emerges phallically from…a late-stage animal gastrula?, and a cartoonishly idealized one at that? and…next to the alga there’s a siphonophore (nowhere near the scyphozoan) and…oh look, apparently the clade Panarthropoda does appear to cluster in Bauplan Space as well,,, but but one of them’s a larva (lepidopteran adult not depicted) and but a different holometabolous insect is off on a separate branch that does seem to include an accurate developmental stage of that adult…and speaking of which, there’s an actual trochophore larva on there elsewhere, leading to a polychaete, though essentially identical larva also develop into adult mollusks…

It’s unique.

I must confess, those drawings are really fancy.

omg there are TWENTY-FOUR Figures. All so detailed and imaginary…except the depictions of actual vertebrate skulls and, huh, zebrafish development.

I am only a high school graduate, from the US public school system.

Most of what I have picked up about embryonic development has come from reading Dawkins;. I can’t say I know all that much, but that I found the processes… gastrulation, layers, invagination, segmented body plans and hox genes… to be fascinating and rather beautiful.

I do know just enough to say this is all fantastical bullshit.

Is this how we get ManBearPig?

Please. I’d like to forget there was a zebrafish staging series in there.

Which had no relevance to anything, anyways.

I really thought that warning would do it, but you were right. I could never have been ready for fig. 2.

In case anyone may have missed the actual news about it, Dendogramma not only does not belong in the same structural group as rotifers and single-celled algae, it is apparently just a piece of a larger siphonophore.

Lunacy. Aside from that I will also say that he is certainly passionate in his lunacy.

Sheesh. I was quite proud of my paper in Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. Still, it was 15 years ago; maybe standards have slipped?

Ballonn animals might be useful if you want to float in the Jovian atmosphere (is in a story by Arthur C Clarke). So Pivar’s critters are at least pre-adapted for life in space….

Clearly you’ve never stuffed a dozen roses down the throat of a dead salmon. Okay, I haven’t either, but it seems like it would work. In fact, it’s my new “theory” of the evolution of vases. Elsevier you say?

Scientific illustration is really persuasive when it’s done well. I know that artists that do it make BANK, which is probably why the only people who can afford them are Texas schoolbook publishers and rich crackpots.

The reporters working the science beat for CNNN don’t want your tables or to interview some beardo talking head in front of a centrifuge, they want awesome pictures shapes turning into shit, in just such a way that it leaves the viewer to surmise a process where none exists.

(See also: everyone’s continued fascination with the Voynich manuscript.)

Long ago I read the Foundation Trilogy by Assimov. In the early story the Foundation recognizes the imminent collapse of the empire by the pseudo science relied on by its emissaries. I never thought I would experience such regression in real life but it’s happening around the world. It’s insane. We have to defend the science institutions and processes at all costs.