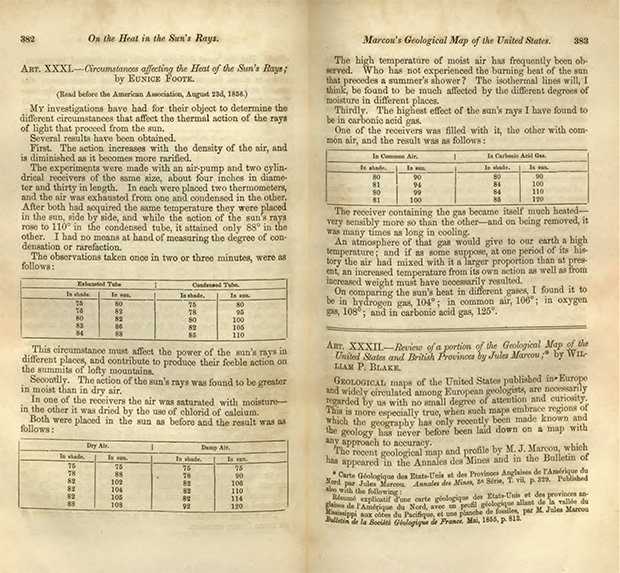

If you want a text version of this article, and description of the tables in it, click here.

For some time now, I’ve had a basic history of climate science more or less memorized. It’s useful to know what we knew and when we knew it, particularly when talking to people who still believe long-debunked misinformation like the idea that the theory of man-made global warming was a post-hoc creation to explain observed warming.

For that entire time, I have been wrong about who first discovered the role that carbon dioxide plays in Earth’s climate.

My go-to narrative generally went from Fourier in the 1820s, to Tyndall in the 1850s and 1860s, to Arrhenius in the 1890s and early 1900s, to Keeling in the 1950s and 1960s. It’s a decent map of key moments in our understanding of CO2 and the global climate, and an effective demonstration of the ways in which the theory was developed, and how it was -and is – a predictive theory that has been supported by a vast body of evidence since its inception.

With simplicity, however, comes inaccuracy. I do not subscribe to the Great Man theory of history – none of the men listed above made their achievements alone, and all of them built on the work of people who had gone before. They were part of communities of people working to understand the universe. The act of singling them out to create a simple, punchy narrative necessarily hides the work of countless other people that contributed to the publications that “history” chooses to single out.

My error, however, goes beyond this necessary over-simplification of history. The reality is that Tyndall, for all his many accomplishments, should not occupy that spot in the story. That place rightfully belongs to one Eunice Newton Foote, who published on the role of CO2 in our climate in 1856 – four years before Tyndall did. Whether through ignorance or malice, Tyndall did not reference her work when he published his own work on the subject. As my discussion of communication between scientists implies, and this linked abstract notes, “From a contemporary perspective, one might expect that Tyndall would have known of her findings.”, particularly since much of that communication is centered around such publications.

Beyond her work as a scientist, Foote was active in the movement for women’s suffrage in the United States, and was a signatory on the Declaration of Sentiments from the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention.

For a woman like Eunice Foote—who was also active in the women’s rights movement—it could not have been easy to be relegated to the audience of her own discovery. The Road to Seneca Falls by Judith Wellman shows that Foote signed the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention Declaration of Sentiments, and was appointed alongside Elizabeth Cady Stanton herself to prepare the Convention proceedings for later publication. As with many women scientists forgotten by history, Foote’s story highlights the more subtle forms of discrimination that have kept women on the sidelines of science.

Foote’s role in history was uncovered by researcher Raymond Sorenson, who published a paper on her in 2011. The greatest service historians provide to us is in their work to sort through the various accounts and records of history, and dig up truths about our past which are so often buried under layers of ego, bigotry, and political power games. In a society founded on science, that lionizes those who first discover new facts about the world, it’s good to see recognition of a woman whose efforts were wrongly ignored for so long.