This was originally posted in February of 2016, before I came to Freethoughtblogs. I’m reposting it here because I think it’s worth having around, and because it’s relevant to a post I’m currently working on relating to global dimming.

Over the last couple decades, the world’s business and political leaders have gradually come to understand that climate change is something that cannot be ignored. Every year, the immediacy and severity of the problem have become clearer. Sea level rise, seasonal changes, and even evolutionary changes in response to the rise in planetary temperature have all made it clear that the entire planet is changing around us, and that ignoring it could have devastating results.

Living, as we do, in a society that values money so highly, some of the responses have been predictable. In particular, businesspeople like Bill Gates have been pushing the idea of geoengineering as a solution. Geoengineering, in this context, is a catch-all phrase for deliberately tinkering with Earth’s climate and the mechanisms that affect it. The problem with this is that the term is so broad it’s almost useless. It can apply to things like planting more trees, and it can also apply to colossal structures in space to reduce incoming sunlight.

One of the most commonly discussed geoengineering solutions is iron fertilization of the ocean. The basic idea is simple – iron is a limiting nutrient in the ocean, so putting iron particles in the ocean will stimulate the growth of photosynthetic plankton, which will pull CO2 out of the atmosphere. The idea is that when the plankton die, a sizable amount of their mass will sink to the bottom of the ocean taking that carbon with it.

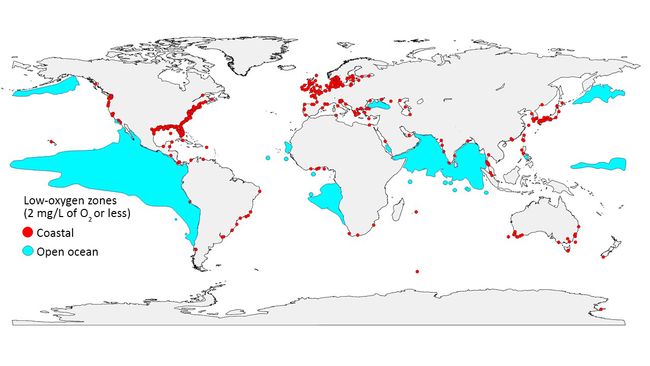

It’s not really clear how well this works in practice. Some studies have indicated that it would work, while others indicate that it might not have much effect, and some people have raised concerns that it might actually result in eutrophication and dead zones.

Newly published research now indicates that because iron is not the only low-availability nutrient in the ocean, the algal bloom from iron fertilization in one part of the ocean might pull other nutrients, like nitrates and phosphates, out of the water, starving plankton farther downstream along the oceanic currents.

It’s tempting to simply wave away geoengineering as a bad idea that we should bury and be done with. There are countless ways that it could go horribly wrong, especially when enacted by billionaires like Gates and his ilk, who have little to no understanding of the ecosystems with which they want to tamper. With the possible exception of planting more trees and creating more wild spaces (which would, without question, work), pretty much every proposal for geoengineering has the potential to have devastating side effects that could make life on Earth much more difficult.

There’s one compelling reason not to throw it away altogether. The reality is that we are already engaged in geoengineering, and there is no question that the path we’re currently on will end badly. Like it or not, humanity has become a force of nature. The size of our population and the scale of our technology mean that we exert a global influence of the chemical makeup of our planet’s oceans, atmosphere, land masses. Currently, we are engaged in the kind of geoengineering that Svante Arrhenius calculated was possible over a century ago – raising the planet’s temperature by increasing greenhouse gas concentrations.

For the sake of our own long-term survival, not to mention the rest of life on Earth, we need to come to terms with the fact that our species exerts a global influence, and we need to take deliberate control of that influence. We are already geoengineers, we’re just not taking responsibility for it. It’s past time to do more than simply work on reducing our fossil fuel use – we need to think about how we manage the surface of the planet we live on, and how we can manage it for the benefit of all life on Earth – ourselves included.

Because right now, we still seem to be pretending that we can just stop having a planetary impact, and with our population headed for 10 billion in just a couple decades, that is the one option that is no longer available to us.

Unfortunately, life costs money, and my income from this blog has yet to meet minimum wage for the time I put into it. If you can afford to, please consider pledging a couple dollars per month or so through my Patreon. This will help me continue creating and improving this blog by keeping a roof over my head, and food in my carnivorous pets so they don’t eat me. Crowdfunding requires a crowd, so if you can pitch in a little, it would help a great deal!