The Probability Broach, chapter 8

For the second time since arriving in this world, Win Bear has narrowly escaped being murdered – this time in his bed, while he was still recuperating from the last attack.

The intruder was wounded in the struggle, but got away. Win’s counterpart, Ed, is searching for any evidence that he left behind:

He examined the empty window frame, leaning outward for a moment. “He left his ladder behind. Wait a minute… something here just below the sill.” He held up a plastic box the size of a cigarette pack, hanging from a skein of wires. “A defeater. Damps the vibrations caused by forced entry. Complicated, and very expensive. Only the second one I’ve seen since—”

“If that thing makes a humming sound, he should demand his money back. That’s what gave him away.”

“Excess energy has to be given off somewhere—heat or sonics. Maybe it just wasn’t his day.”

I snorted, surveying the shambles. “You didn’t see him lying on the ground out there?”

“No. Missed him by a mile. He probably picked up a fanny full of splinters, though.” He nodded toward the shattered window.

L. Neil Smith doesn’t linger on the implications of this passage, but I will: There are businesses in this society making products whose only use is to assist people to rob and kill others. There’s no purpose for a “defeater” that doesn’t involve crime.

Like several places in Atlas Shrugged, the author is saying one thing even as his own writing shows something else. Smith insists that the North American Confederacy is a peaceful utopia, where crime is virtually unknown because everyone carries the means of self-defense. People with criminal intent – he wants us to believe – are deterred by the knowledge that all their potential victims are armed.

What it actually shows, just as a critic of anarchism might point out, is that life without laws or government is far more dangerous. Widespread gun ownership doesn’t prevent crime; it just incentivizes criminals to get even bigger guns to overpower their victims. Weapons and other devices that would be banned in our world (in civilized countries, at least) are completely legal to manufacture and own.

You can put spinning spikes or flamethrowers on your car’s wheels, Mad Max-style, to get revenge if some jerk on the highway tailgates you. You can bury land mines in your front lawn or rig up lethal booby traps around your property, protecting against intruders but also endangering innocent visitors. You can set up machine guns or artillery pieces aimed at your neighbor’s house, just in case he does something that annoys you.

The next line drives this point home. Ed is apologetic about Win’s latest brush with death:

“My fault, really. I considered putting on extra security, but decided the autodefenses would be enough. Now I’ve let you get attacked again, in my own home.”

Ed’s house has “autodefenses”, not further described. Does everyone have these? You wouldn’t pay for something if you had a reasonable expectation of never needing it.

It goes to show, again, how the writing undercuts its own premises. Smith insists that everything is cheap in the NAC because anarchy is more efficient. There’s no wasteful government leeching off people’s productivity, so they get to keep everything they earn.

But his own plotting shows the opposite. Without a government, life isn’t cheaper. People just have to pay out of their own pockets to supply all the services that a government would normally provide.

You have to supply your own security, and if those “autodefenses” aren’t enough, you have to hire people to patrol your house (which Ed does after this scene).

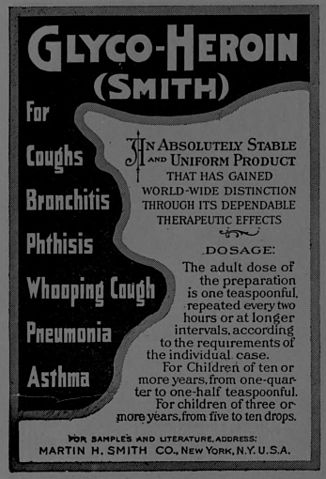

If you care about your house burning down, you have to pay for a private firefighter service. You have to pay for private school instead of attending public school. You have to be your own bank regulator, investigating any bank you do business with to determine if they’re likely to collapse and lose your life savings. You have to be your own consumer-safety advocate, inspecting every product you buy to see if it’s toxic, flammable, or otherwise hazardous. You can probably think of more examples.

Given Ed’s description of the defeater as “expensive” and better than his home defenses, there’s yet another unpleasant implication. In this anarcho-capitalist utopia, everyday life is an arms race.

If you can outspend someone and buy tech to overcome their defenses, it’s completely feasible to kill them. Or to put it another way: if someone wants you dead and they have more money than you, you’re in big trouble. And if you’re poor (and can’t afford your own private security or a house with “autodefenses”), you have no chance at all.

After all, there’s no higher authority to investigate or hold criminals accountable. If you’re lucky enough to catch an assailant in the act, you can shoot them. But if a thug or a hitman succeeds in murdering their victim, they get away scot free. If Win’s midnight attacker had succeeded in murdering him in his bed, he could have escaped safe in the knowledge that no consequences would follow.

Even if the victim has friends or family who can afford to hire a private investigator, it’s unclear what that person would be able to do, since there’s no legal system. (Smith takes a stab at answering this question later in the book – his solution involves private arbitration and restitution or exile as punishments – but it has some very obvious holes, which we’ll go into.)

What it adds up to is this: if you’re living in Smith’s ancap society, you have to be on guard against attack at any moment, for your entire life. You have to protect yourself, because no one else will protect you. Win would have been killed, if not for the stroke of luck that he happened to be awake when the hitman broke in, and that’s a good template for how things would work in the North American Confederacy.

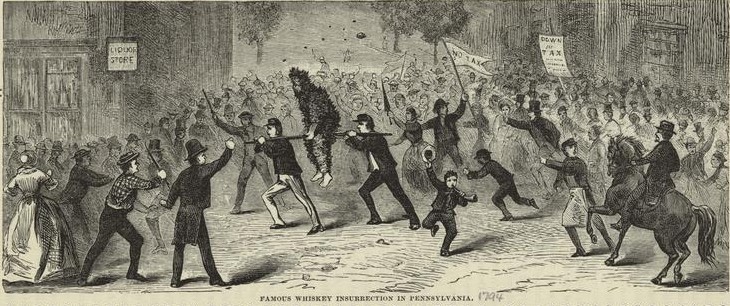

There’s good reason to be paranoid in this world. Everyone is armed, and everyone ought to be on a constant hair trigger, for fear that some casual encounter could be a robber or a murderer about to make their move. This society shouldn’t be peaceful and civilized, but a melee of bloody violence.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series: