The Probability Broach, chapter 9

L. Neil Smith has a serious grudge against the Constitution.

It’s not just that he disagrees with its goals, as you’d expect from an anarchist. Like a good sovereign citizen, he claims the whole thing was illegal. He denounces it as a grand conspiracy led by Alexander Hamilton. As Smith’s narrator Win Bear tells it:

He and his Federalists had shoved down the country’s throat their “Constitution,” a charter for a centralist superstate replacing the thirteen minigovernments that had been operating under the inefficient but tolerable Articles of Confederation. Adopted during an illegal and unrepresentative meeting in Philadelphia, originally authorized only to revise the Articles, this new document amounted to a bloodless coup d’état.

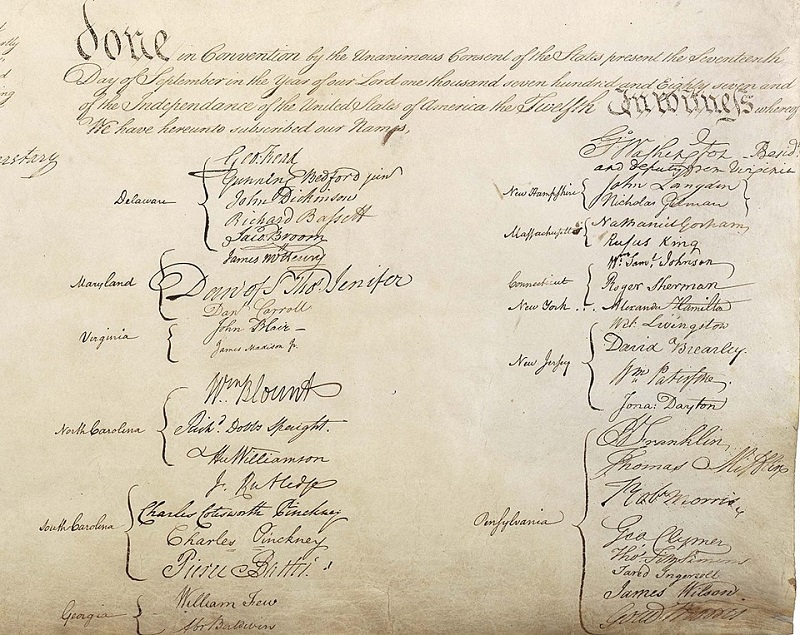

Funny—as near as I remembered, these were the same events that had happened in my own world. But in the eyes of my new friends, historic figures like John Jay and James Madison became villainous authoritarians. Of seventy-four delegates chosen to attend the Constitutional Convention, nineteen declined, and sixteen of those present refused to sign. Of the thirty-nine remaining, many of whom signed only reluctantly, just six had put their names to the original Declaration of Independence.

It’s true that not all the delegates to the Constitutional Convention were willing to sign, but that’s not surprising. It’s easy to reach agreement that an existing system isn’t working; it’s harder to agree on what to replace it with. Governing always involves compromise, and no political system makes everyone happy. That’s not a challenge unique to America, but something that every band of revolutionaries throughout history has discovered.

Smith roars that the Constitutional Convention was an “illegal” meeting, but he omits a relevant fact: the delegates met to revise the Articles of Confederation because it was very clear that they weren’t working.

Under the Articles, America was more like a loose alliance of thirteen separate nations. There was a national Congress, but it had no power to levy taxes. To fund anything it voted for, it had to beg the states to contribute.

This created a Prisoner’s Dilemma situation. Each state had a selfish incentive to sit out and let the others do the unpopular work of raising revenue—and because they all reasoned the same way, almost none of them ever did. In 1786, Congress requested $3.8 million from the states to pay national obligations, and got… $663.

The early American republic was chronically broke and hamstrung. It couldn’t pay the debts it had taken on while fighting for independence. It couldn’t even pay its own soldiers.

Smith puts huge importance on the Whiskey Rebellion. But there were other, equally serious crises that he ignores because they don’t fit with his worldview that blames centralized government for all evils.

In March 1783, in the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy, officers in the Continental Army were enraged over not receiving their promised pay and pensions—in some cases, for years on end. They circulated a letter hinting at plans to overthrow Congress. George Washington personally intervened to defuse the conspiracy.

But he couldn’t stop the next one: the Pennsylvania Mutiny of June 1783, when Congress was surrounded, mobbed and threatened by hundreds of angry, rebellious soldiers demanding their promised pay. They had to flee Philadelphia, the seat of government at the time.

Last but not least, there’s Shays’ Rebellion. It was an uprising of rural Massachusetts farmers, many of them veterans of the Revolutionary War, who were angry about state taxation when they themselves hadn’t been paid for their service. They attacked local courts, preventing them from meeting, and tried to storm a federal armory and seize its weapons to overthrow the government. Once again, the federal government was helpless to intervene. An alliance of private citizens paid out of their own pockets to fund a private militia to suppress the rebellion.

Meanwhile, America faced pressure from foreign powers. Spain, which controlled the Mississippi River, closed it to American navigation—strangling trade from western regions—and pressured Americans to swear allegiance to Spain in exchange for access. Once again, there was nothing the U.S. government could do.

These repeated crises made it clear that the fledgling American state was too weak to govern, and risked being torn apart by internal uprising or subjugated and carved up by European powers. By the time of the Constitutional Convention, there was widespread recognition that something better was needed. It wasn’t a sinister conspiracy, as Smith imagines.

Smith’s fuming about a “coup d’etat” or the Constitution being “shoved down the country’s throat” ignores another obvious fact: the delegates to the Constitutional Convention didn’t force a new government on the nation at gunpoint. How could they have?

There was no skullduggery or subterfuge. The new Constitution was presented and debated in public over the course of several years. It took until 1790, but all thirteen states ratified it democratically. To assuage some holdouts’ concerns, the Bill of Rights was added—arguably a step up from the Articles, which had no such thing!

After the Constitution was ratified, Smith’s alternate history proceeded the same as ours, until the Whiskey Rebellion. We’ve already heard about Albert Gallatin, and he makes another appearance in this chapter.

In 1794, a Pennsylvania gentleman stepped into the fray. A former Swiss financier, Albert Gallatin disapproved of the way Alexander Hamilton handled the nation’s checkbook. He organized and led the farmers and began convincing federal soldiers they were fighting on the wrong side…

Thus “fortified,” the 80-proof revolution marched on Philadelphia. Washington went to the wall, Hamilton fled to Prussia and was killed in a duel in 1804. Gallatin was proclaimed president.

Smith acknowledges (vaguely) that the Articles of Confederation gave rise to some problems, which he tries to address as follows:

Economic problems that had precipitated the Constitution Conspiracy were solved with a new currency, backed by untold acres of land in the undeveloped Northwest Territories.

…Gallatin’s land certificates were redeemed, the last money ever issued by a United States government. He served five four-year terms in all, and lived long enough to see his own peculiar brand of anarchism begin spreading throughout the world.

There’s a lot of furious handwaving in this passage. I’ll limit myself to pointing out the top two problems.

In Smith’s history, America’s Revolutionary War debts were settled by a new currency, backed by land in the Northwest Territories. Except… the Northwest Territories were occupied at that time—by the British—who refused to relinquish them because, again, the Articles of Confederation government was shirking its financial obligations under the Treaty of Paris that ended the war!

Smith expects us to believe that the British crown would accept land they already controlled as payment for the debt we owed them.

In reality, the British didn’t withdraw from those territories until the 1794 Jay Treaty, negotiated by that villainous authoritarian John Jay. (There were also Native Americans living there—more about this next week.)

Second, to re-raise a point I made before: How can a currency be backed by land, unless there’s a central government that can protect and adjudicate claims of ownership?

In the anarchist society that Smith envisions, there’d be nothing to stop crowds of claim-jumpers and squatters from taking over territory that other people thought they owned. Any currency whose value was predicated on being able to redeem it for parcels of land would rapidly become worthless.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series:

The longer this book goes on, the more it reminds me of a book club I was in 30 years ago. The club agreed on books to read, which mostly consisted of sci-fi and urban fantasy. When a member suggested a cyberpunk book, one guy objected without having a clue what it was he was objecting to. He kept trying to interject, “I don’t want to read a cyberpunk book because…” He really had no idea what cyberpunk was or wasn’t, but he was objecting on the basis of what he imagined it might be. And his imagination had nothing to do with reality.

Similarly, Smith is creating his fantasy world because of things he’s objecting to in the real world, but it’s obvious he has no grasp of the real world.

Yeah, someone who mentions “villainous authoritarians” in reference to anyone other than ACTUAL SLAVE-OWNERS AND SLAVE-TRADERS is not someone we can take seriously.

So the Confederacy wasn’t paying its debts? Surely in a libertarian society such a persistent bad-behaver would be shunned by all, and no one would engage in any business transaction with them, right? I mean, isn’t that the enforcement method – bad reputation leads to an (unorganized!) boycott?

Of seventy-four delegates chosen to attend the Constitutional Convention, nineteen declined…

Did Smith say anything about Patrick Henry, who declined because he wanted more of a theocracy, and knew the other delegates would refuse any such plan?

For that matter, did he address (pro or con) the claims his wingnut comrades now promote about Xian nationalism?

Win remembers from his history books “Patrick Henry smelling a rat at Alexander’s steamroller party.”

Patrick Henry is only mentioned once in this book, very briefly. When Win Bear recounts what he vaguely remembers about Federalist and Anti-Federalist founders clashing with each other, he describes it as “Patrick Henry smelling a rat at Alexander Hamilton’s steamroller derby”.

Nothing is said about Christian nationalism or theocracy. For that matter, Christianity and religion don’t play any part at all. This book has that in common with Atlas Shrugged: everything is reduced to economics; there are no other factors driving human behavior as far as the author is concerned.

Which is very misleading about the events of the founding of the US. A bunch of the events and negotiation centered on religion. There was a push for a national religion and a counter-push, this argument laid the basis for religious freedom in the US today and impacted the writing of the Constitution and amendments.

I could understand if he didn’t understand the religious arguments. It’s a complex topic that involves religious principles and groups that don’t really exist any more. Pretending it didn’t happen is bad historical revisionism.

Smith my be intentionally misleading or he may not understand himself. Considering how hard of a libertarian cult follower he is I can’t tell which it is.

‘Both’ is still on the table.

Which, yeah…. LOLWUT?

The entire concept of Freedom of Religion was intensely controversial at the time, with hellfire and damnation preachers giving rousing sermons about how the country was going to be sold to Satan if a proper state church wasn’t set up. Of course there already were state churches in the various original thirteen colonies, and that was part of the problem: the Puritans, in particular, had escaped religious persecution and come to New England so they could be the ones doing the persecuting instead. (Whenever somebody starts talking about the ‘War on Christmas’, just remember, the Puritans were the ones that actually did ban Christmas and tried to punish any company that gave its employees Christmas off. One of the founders of Rhode Island was a Baptist who had escaped from Puritan-controlled Maine and deliberately championed Freedom of Religion so people like him wouldn’t be persecuted again.)

I think it was Benjamin Franklin who actively talked to ‘Mohametans’ (Muslims; the concept that they didn’t actually worship Mohammad was rather alien to most Christians) to convince them that the nascent United States was not going to throw them out for not being Christian, and things like that were part of the reason why Freedom of Religion won; the realization that any State Church would effectively throw out a lot of people who were already contributing to the country.

So, yeah, people like David Barton or anybody else who says the U.S. was always a ‘Christian nation’ are wrong: the Christian Nationalists had that argument in the late 1700s and they lost. Instead a lot of them decided that obviously this idea of ‘no state religion’ couldn’t last forever because the ‘masses’ couldn’t be trusted to control themselves and as long as they kept their churches going eventually one of them would be the one to actually pick up the pieces when the nation collapsed without the Hand of God guiding it (through them, of course). Much like a lot of the southern plantation owners who considered themselves as unrecognized Barons only went along with this whole ‘democracy’ thing because obviously it wouldn’t be able to last long and they’d be in place to properly rule people when it collapsed.

There were indeed several villainous authoritarians involved with the Constitution; for the most part, they either lost or only got compromises. (3/5 of a person, anybody?) But they got enough of those compromises to help make things more difficult for generations to come.

Interesting, that she shares this view with the loathed marxism.

As with the bit with Jefferson in the previous posting, here’s another important example where we are simply told and never shown. What did Gallatin actually say? Where is the stirring rhetoric that he offered in opposition to federalism?

LOL ¯\_ (ツ)_/¯ It says he was convincing! Why are you not convinced?

If you work for us today, we will gladly pay you in coupons that you can someday redeem based on land that we don’t own or control now, and will never control in the future (given anarchic principles). Why are you not convinced?

Yeah, what Katydid said @1.

…“Patrick Henry smelling a rat at Alexander Hamilton’s steamroller derby”.

Alexander Hamilton had a steamroller? And what would a “steamroller derby” look like? Anything like a tractor-pull?

This book has that in common with Atlas Shrugged: everything is reduced to economics; there are no other factors driving human behavior as far as the author is concerned.

It’s almost as if both authors were just mentally unable to deal with the reality of human beliefs, or how they might affect their simple anarchic fantasy-world.

And I suspect that’s why so many right-wing Christians supported Rand and libertarianism, quietly or not: they offered a fantasy of White Christian nationalism without mentioning the much less pleasant reality of Christian churches throughout US history.

Raging Bee @ # 5: … I suspect that’s why so many right-wing Christians supported Rand and libertarianism, quietly or not: they offered a fantasy of White Christian nationalism without mentioning the much less pleasant reality of Christian churches throughout US history.

Miss Rand (as I think she’d prefer being called) quite vocally and frequently proclaimed her atheism and her disregard for those who snapped the leash of christianism to their own collars, so the True Believers in both Jesus and Ayn had a zigzag tightrope to walk indeed.

Pfft, no biggie — they routinely ignore what their own Lord & Savior plainly said, so ignoring what Miss Rand said is no problem. Miss Rand hated all the same people they hate: secular liberals who seek to use state power to enforce everyone’s legal rights and keep both churches and corporations under control.

Did they have steamrollers back then?

Hmm..

Source : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steamroller#History

Did you know that there’s a Patrick Henry College (www.phc.edu) in Virginia? When you google them, this is what comes up on their homepage: “Patrick Henry College stands apart from all other conservative Christian colleges. PHC exists for Christ and for Liberty and challenges the status quo.”

So…I guess Bob Jones and Pensacola Christian College and Liberty University and all the others don’t stand for any of these things?

According to Wikipedia, it teaches, “government, strategic intelligence in national security and stewardship”. It was founded by the Home School Legal Defense lawyer.

Apologies; fell down the rabbit hole with the college and didn’t circle back to finish the thought: in this case, that whatever Smith imagines Patrick Henry was likely has no bearing on reality, but wherever he got his his ideas in this 1980s book, a Christofascist college has also adopted those fantasies and built a college around it to “educate” homeschooled kids.

I find this highly interesting. In 2010, I homeschooled one of my kids for high school–I was stationed in Northern Virginia and my kid was ready for community college for most classes and it made the most sense to declare myself a homeschooler to the state and send my kid to community college for most things and an online high school for the rest. But because of that, I had to join a homeschool umbrella group which included meetings with the group. While there were parents who wanted a solid education and an independent future for their children, we were outmatched by Christian Nationalists and others who met the worst stereotypes of families who homeschool. The fact that the HSLDA leader started Patrick Henry College does not surprise me in the least.

Whelp, this series and deconstructing set of reviews (& the comments here) sure is one way of learning some fascinating (relatively) “ancient” American history..

For an Aussie who knows not that much really of it.

Thanks.

For non-USAians, please feel free to share your experiences and your history!