When I recently read up on DW-NOMINATE, I learned a few things about certain political figures. DW-nominate gives every senator a score based on how left/right their voting behavior is, and sometimes the score does not match the senator’s public image.

In the 115th congress (2017-2019), the leftmost senator was… Elizabeth Warren. Not Bernie Sanders, where did you get that idea? After Elizabeth Warren, is Kamala Harris. Then we have another presidential hopeful, Cory Booker. And finally, we have Bernie Sanders–tied with Tammy Baldwin.

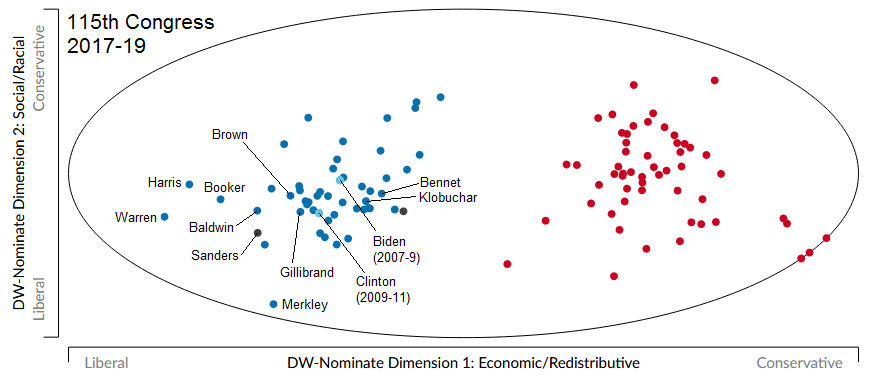

I made a plot! It’s copied directly from Voteview, with labels added for certain senators of interest.

Mostly, I picked out senators who are running for president (Warren, Harris, Booker, Gillibrand), or who we think might run for president (Sanders, Biden, Brown, Klobuchar, Bennet, Merkley). Biden and Clinton haven’t been on the senate for a while, so I added in their older scores (keeping in mind that the Democrats used to be further right as a whole).

I don’t include any presidential hopefuls in the House of Representatives, because they have a separate, incomparable score. I note, however, that Beto O’Rourke, John Delaney, and Tulsi Gabbard are a bit to the right of Democratic median. And if you’re wondering about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, she is near the right edge of the Democratic party, and a total outlier in the downward direction. So Ocasio-Cortez isn’t very liberal in the conventional sense, but she is very something.

How skeptical should you be? Oh, be skeptical, be very skeptical. But while we’re at it, let us also be skeptical of the public image of these politicians, which might be based on the whims of social media. Just trusting numbers you don’t understand is a garbage epistemology, but just reacting to what you hear on social media (and ignoring what you don’t hear) is pretty garbage too.

I just want to make a few observations, so that we might be skeptical for the right reasons.

1. DW-NOMINATE is only based on votes in congress. So if you’ve been hearing about Kamala Harris’ record as an attorney general, that’s not included. One may be skeptical of a score that doesn’t include Harris’ full record. On the other hand, one wonders how much her attorney record matters if it doesn’t actually impact her voting behavior on national issues.

2. DW-NOMINATE does not use any information about what people are voting on. Instead it uses information about which senators vote in the same way as each other. So if Elizabeth Warren is to the left everyone else, that means that there are occasionally votes where even a lot of Democrats are voting with the Republicans, but Warren is less likely to vote with the Republicans than anyone else. So maybe Warren isn’t truly to the left of Sanders, it’s just that being super leftist means sometimes agreeing with Republicans? And the truest leftists vote for Trump, of course.

3. There’s a second dimension! Voteview labels this as the “social/racial” dimension, but it’s not like there isn’t any social/racial aspect to the first dimension. Basically, it’s the dimension that used to differentiate Northern and Southern Democrats. But then the Southern Democrats switched parties and nobody really knows what it means anymore. But hey, Jeff Merkley and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez are way off to one side of that spectrum, and Bernie Sanders is… in that direction? It’s possible that Sanders supporters particularly value this second dimension.

But there’s a reason that the second dimension is portrayed as “squashed” relative to the first. Because the first dimension explains about 83% of the votes, and the second dimension only explains about 2% (perhaps a really important 2%). At least, these are the percentages I’ve heard for DW-NOMINATE in general. Empirically, adding more dimensions doesn’t help. About 15% of the time, senators vote in the opposite way from what they are expected, but they do not do so in an organized way. So you might say Sanders or whoever has a few voting quirks, and perhaps you happen to like those quirks, but those quirks definitely do not constitute some sort of faction among Democrats, they are just quirks.

I want to make clear, the most left candidate isn’t necessarily the “best” candidate, and one may reasonably prefer a candidate that’s more towards the middle. I’m just poking a bit of fun at Bernie Sanders’ super leftist image, which may have been accurate in 2016, but is not clearly the case relative to the 2020 candidates.

Personally, I think the biggest takeaway from all this is that for whatever differences Democrats might have from each other (or from independents like Sanders), they’re pretty small compared to the gap between Democrats and Republicans. Even a brainless algorithm can see that.

I think such a measurement is pretty arbitrary and not really very informative. Everyone has pet causes and battles, and we can at least hope they think for themselves at least some of the time. In any case, measuring Sanders’s leftness is bound to cause some confusion, since he’s conspicuously in disagreement with many Democrats on free trade, and owing to his Vermont constituency he’s traditionally been conservative on gun control. Those two issues alone are enough to skew any overall score without really helping us out much.

When Trump denounced socialism, Warren stood and cheered; Bernie was less impressed.

If any system comes up with the result of AOC being to the right of Pelosi, Schumer, Booker, or Harris, then that system is junk.

@Matthew Currie,

Right, and I don’t expect Sanders’ positions on free trade or guns to show up as another dimension, because guns and free trade are probably a small fraction of votes, and there probably isn’t much of a Democrat faction that disagrees on the same two issues.

@polishsalami,

Here’s a thought: political positioning relative to the word “socialism” is mostly meaningless.

I’m not sure how far I would believe AOC’s currently calculated score, being as it is based on only one month of data, and a month dominated by the government shutdown. There’s something there though. I was looking at her votes earlier, and there are a bunch where AOC is the sole dissenter among the Democrats in a party-line vote. I’m not sure what these votes were about, but they looked shutdown-related. Maybe someone who’s followed it more closely could tell me what that’s about.

I would recommend this recent post, and Corey Robin in general: Beer Track, Wine Track, Get Me Off This Fucking Train. Robin argues that there’s an important dimension of political leadership, a coherent ideological narrative, separate from specific policy proposals. I think Robin’s point generalizes to this case, with policy proposals mapping to voting with the Democrats.

It’s not clear from your explanations, but I think it’s very misleading, or at least missing something really important, to equate the Democratic party with the left. I’m guessing that if someone always voted with the majority of Democrats, they would have a score of 1 (and always voting Republican would have a score of -1); if so, their map would represent partisanship, and not necessarily a real left-right axis. For example, I’m guessing that if 51% of Democrats and 49% of Republicans voted for some “centrist” policy, then a left-dissenter would look “right”, because they voted the same the majority of the Republicans.

It is my contention that the Democratic Party is a fundamentally right-wing organization; they are simply a lot less right-wing than the Republicans.

@Larry,

Thanks for the link. I often appreciate the links you share.

Under the assumptions of the DW-NOMINATE model, everyone has positional preferences rather than directional preferences. Thus the Democratic median is not associated with the left direction, it’s just associated with a position. Even scores of -1 and +1 don’t refer to directions, rather it means that the position is so far off that the algorithm had to apply artificial constraints to prevent it from messing up the model.

Of course, the left-right axis is defined in such a way that maximizes the differentiation of the candidates, which is to say that it mostly maximizes the differences between the parties. So in that sense the Democrats are associated with a direction, and I agree that that direction primarily represents partisanship.

For those of us who are very far from of Congress’s center, we might initially guess that our own preferences are for all practical purposes directional, and thus prefer one of the candidates on the outer edges of the Democratic party. But I think this needs to be interrogated. Does the “direction” that I prefer correspond to the minus direction of DW-NOMINATE? Not necessarily. Although I mocked the idea that being super leftist means sometimes agreeing with Republicans, you could indeed argue that a coherent leftist worldview might sometimes support Republican positions, because it’s not about partisanship, it’s about doing right.

All I can say is that for me, Sanders’ position as leftmost candidate was one of his major selling points, and now that he’s lost that, he’s lost a lot of his glamor. I not really into his whole ideological narrative, whatever that may be.

This hypothesis is equivalent to saying that the true center is to the left of the Democratic party, but I’m just not sure that the concept of a true center is meaningful to begin with.

Under the assumptions of the DW-NOMINATE model, everyone has positional preferences rather than directional preferences.

But the assumed “position” has nothing to do with ideology, it just means, what? A propensity to vote with or against the majority of Democrats/Republicans? Maybe I should bite the bullet and just look at the actual model.

[Y]ou could indeed argue that a coherent leftist worldview might sometimes support Republican positions, because it’s not about partisanship, it’s about doing right.

It’s not necessarily about supporting Republican positions, but failing to support (bad?) Democratic positions.

Sanders’ position as leftmost candidate was one of his major selling points, and now that he’s lost that, he’s lost a lot of his glamor. I not really into his whole ideological narrative, whatever that may be.

I dunno, Siggy. You are, for example, creating a ideological narrative about asexuality, and good on ya, mate. More importantly, everyone I think buys into an ideological narrative: either the status quo or something different. If you like the status quo and think the important task is to adjust it, then that’s what you like, but that doesn’t mean you’re not ideological; it means you’re buying into the existing dominant ideology.

In The Big Lebowski, Walter Sobchak (John Goodman) says, “I mean, say what you want about the tenets of National Socialism, Dude, at least it’s an ethos.” And I think that’s Robin’s point: the mainstream Democratic party is not promoting an alternative ethos to neoliberal capitalism, but people are profoundly unhappy with the ethos of neoliberal capitalism at a very fundamental level. So Robin divides the Democrats into those, such as Elizabeth Warren, who want to preserve the neoliberal capitalist ethos but change things at the margin and those, such as Bernie Sandes, who want to fundamentally change the ethos.

@Larry #6,

I talked about in an article I wrote last year. The assumption is that each yea and nay vote is associated with a particular position, and candidates prefer to vote for the one that is closer to their own position (with some noise added to their preferences). Sometimes there will be votes where both yea and nay are relatively far to the left, and these will unite Republicans while dividing Democrats. And when the Democrats are divided, Warren and Sanders tend to be on one side, while Klobuchar and Bennet are on another.

You might have misinterpreted what I said. I wasn’t saying I don’t buy into ideological narratives, I was saying I don’t buy into Sanders’ ideological narrative.

And what are Warren and Sanders’ ideological narratives? Corey Robin picks out those two candidates as having coherent ideological narratives, but never says what he believes is their content. You know, I don’t really follow these candidates that closely, and would not have thought to pick those two out.

I read your article, but I still don’t understand the model they’re using. And I did misunderstand what you said; my apologies. And I misremembered Robin: he claims Warren does have a coherent narrative. He’s contrasting Sanders and Warren with Harris and Booker. And indeed, Robin’s article that I linked to doesn’t talk about particulars of anyone’s ideological narrative.

I probably do follow the candidates a little more (but not much more) closely than you do, and I concur with Robin’s opinion. They both have a narrative: Warren’s is that capitalism must be radically better managed, the state (i.e. the professional-managerial class) needs to exert power over the capitalist class; Sanders’ is that regulation is insufficient”: we need to start undermining capitalism by moving a lot of economic power to individuals. I’m sure you’ll be shocked that I prefer Sanders’ narrative.

At least that’s how I read it, but I have some serious ideological biases that color how I read candidates, and I’m relying on a lot of other analyses, especially from Naked Capitalism.

@Larry #8,

For what it’s worth, I think most political scientists don’t understand DW-NOMINATE either, they just treat it like a black box, coded in some godforsaken version of Fortran. It’s really hard to find detailed information about the algorithm.

So I read the actual primer. The critical issue for me is that I can’t find a good explanation there for the interpretation of the model, especially on p. 31:

Looking at Congressman McCormack from the 12th Massachusetts district (later Speaker of the House), one sees that he locates somewhat toward -1 on a scale of economic liberalism and conservatism running from -1 to +1. His Republican colleague from the 4th District is far more conservative than he is, as indicated by his score of 0.352.

Looking at the Mississippi Democrats, one sees that they are less economically liberal than their Massachusetts counterparts. Also, they are more conservative on the second dimension. Indeed, Congressman Rankin is maximally conservative on the second dimension, that is, with regard to policies that would change race relations in Mississippi, placing him at +1.

Although I have not studied the math in any great detail, I understand the principles of dimensional analysis. We can just look at votes and find first that two arbitrary dimensions gives us statistically significantly better predictions of votes than one arbitrary dimensions, but three arbitrary dimensions doesn’t significantly improve our predictivity. We scale the coordinates from -1 to +1 and find that on one dimension Democrats generally have one sign and Republicans have the opposite sign, and northerners have one sign on the second dimension and southerners have the opposite sign. All well and good, and finding that a dimensional analysis maps well to both party and location means that the analysis has captured what appears naively to be important distinctions.

But where do the authors get the interpretation of the dimensions? Calling one side of the arbitrary X dimension “liberal” because that’s where the Democrats are and the other side “conservative” because the Republicans are there seems unwarranted. Either one is simply equating “liberal” with “what most Democrats vote for”, which adds no information, or one is making a statement about the content of what Democrats vote for, which, which is not supported (as far as I can see) by a rigorous scientific analysis of vote content.

To be fair, the authors do show how to bring their method to content-based analysis in a rigorous way by applying their analysis to a specific hypothesis about votes for social security, showing that for one specific vote the Democrat-Republican axis was highly significant, and the northern-southern axis less significant.

However, I do not think it is warranted to simply say that just because Warren has a more extreme score than Sanders in the Democrat-Republican axis means that Warren is more liberal. The best I can think we can say is that Warren is “more Democratic-party” than Sanders.

@Larry #10,

My understanding is that at some point they have to look at the content of the votes, and these are compared to the conventional understanding of political historians. For example, maybe political historians say that at this point in history, liberals usually supported policy X while conservatives supported policy Y. They may also have understood such and such congress members to have been liberal or conservative. So then if all the “liberal” congress members and “liberal” policies are towards the negative side, that side probably refers to the liberals. Of course, there’s also room for surprising discoveries, like if some of the “liberal” congress members were actually voting against the “liberal” policies.

“Liberal” is not exactly “what most Democrats vote for”. Maybe there’s a policy that has 100% of Republicans on board, and 75% of Democrats, then the leftmost Democrats might actually vote against their party. But what you’re saying is not too far off from the truth. The problem is that there isn’t really a definition of “liberal” that everyone can agree on. But if you do pick out some definition of liberal and stick with it, it is entirely consistent to say that the most liberal senator is not the same as the one with the leftmost DW-NOMINATE score.