This year’s Nobel prizes for physics were announced yesterday and went to three scientists for their work in developing blue light emitting diodes, something that has had a big impact on technology because without it, we could not create white light.

At an announcement in Stockholm on Tuesday, the Nobel Prize committee awarded this year’s prize in physics to Isamu Akasaki, Hiroshi Amano and Shuji Nakamura. The three men — Akasaki from Meijo University, Amano from Nagoya University (both in Nagoya, Japan) and Nakamura from UC Santa Barbara — produced blue light beams from their semi-conductors in the early 1990s. Until then, we could create red and green light, but blue remained elusive.

Red, blue, and green light combine to make the bright white produced by LED lightbulbs. Bulbs using blue light-emitting diodes are more efficient and have a longer lifetime than old fashioned bulbs (up to 100,000 hours, compared to 1,000 for incandescent bulbs and 10,000 hours for fluorescent lights).

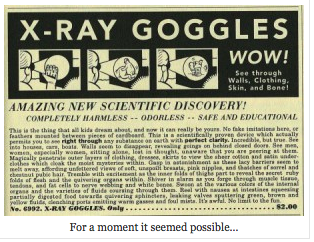

Corey S. Powell takes us back to the huge fuss over the discovery that was awarded the very first Nobel prize in physics, to Wilhelm Roentgen for his accidental discovery of X-rays. While people were excited by it, they worried that it would enable devices like glasses that people could use to see your naked body under your clothes.

Corey S. Powell takes us back to the huge fuss over the discovery that was awarded the very first Nobel prize in physics, to Wilhelm Roentgen for his accidental discovery of X-rays. While people were excited by it, they worried that it would enable devices like glasses that people could use to see your naked body under your clothes.

This reminded me of the ads that used to appear in comic books, selling eyeglasses that promised to give the user X-ray vision like Superman. I know now that they would never work as advertised but as a small boy was intrigued by them. Since I was in Sri Lanka, I could not order such things but I wonder what they actually did and am curious if any reader ever bought them.

It appears that nowadays there are very expensive versions of these devices that use infrared technology that may actually work like those old ads promised, which is kind of disturbing.

I’m surprised that people continue to use the limited lifetime of the light bulb as if it were a limitation instead of a feature of the design. This is an early and very successful example of planned obsolescence.

The power advantage of the LED light bulbs is obvious but the lifetime one is mostly fabricated.

I think some of those “x-ray specs” had an effect similar to aligning your eyes for the wrong depth, so that when you looked at your finger you would see two half-transparent fingers offset from each other, and where they overlapped (where the bone would be) the image was opaque.

I was a sucker and a comic book fan when I was young, and yes, I ordered a pair. In place of lenses they had some type of semi-transparent paper with “whirls” drawn on -- think of the cheesy special effects at the start of the old tv show “The Time Tunnel”. Even then I wasn’t sure how those were supposed to relate to x-ray vision.

dean,

I would likely have bought one too, if I had been able!

“Zero lux” video cameras came close to providing the x-ray specs capability when used in the daylight. They could see people’s underwear through some clothing. My recollection is that Sony actually modified their cameras so the “zero lux” setting couldn’t be used in daylight.

Doing so was a big challenge, since blue photons are more energetic than green ones or red ones, requiring a higher band gap to create them. Furthermore, the electron-hole recombination ought to be a direct one instead of an indirect one that also emits some phonons, reducing its efficiency. The Nobel laureates found that gallium nitride worked, and they then worked out how to make thin films of it and dope those films so as to make diodes.

But now that one can cover the entire range of human vision, one can make LED lamps that are at least as efficient as fluorescent ones, and much more efficient than incandescent ones (light-emitting resistors?). So we’ll be seeing a lot of these in our future.

The first generation of blue LEDs used silicon carbide, which was expensive and inefficient. They were used mainly as colour references in some optical instruments. They were a dead end. Luckily Nakamura found another route.

@Trebuchet: IIRC “zero lux” used the infrared sensitivity of the CCD sensor. Many textiles are translucent to IR. Most cameras these days have an IR filter that prevents it, but the main reason is sharpness of image. In old days the resolution of the image was so poor that colour dispersion from IR didn’t matter much.

However there are now cheap IR cameras. Seek Thermal sells a camera accessory for Androids and iPhones for $200. I might get one for boating purposes. IR should see through fog, because its wavelength is longer than the diameter of a typical fog droplet.

http://obtain.thermal.com/category-s/1818.htm/

Jean @ #1: My understanding is that incandescent lamps, what most people call bulbs, can have very extended lifetimes if they are run on reduced voltage and not exposed to vibrations or impacts. Supposedly, I don’t know if it is still true, but as of the 70s there was an industrial lamp in upstate NY, I remember it as NY, that had run for most of 100 years. I remember a picture of a longish lamp with a long filament zing-zagging along its length glowing a dull orange.

It was pretty common practice for lamps that are difficult to replace, and where a slightly dimmer and redder light is not an issue, to be replaced with commercial duty 130v lamps even though they would be on a typical 120v circuit. With a slightly higher resistance filament they would run a bit dim but last almost twice as long as the regular 120v rated models.

As I understand it the typical 100,000 hour rating on most LEDs is a working average under ideal conditions. That LEDs can have much shorter lives if they get too hot or voltage is not tightly controlled. many manufacturers have shifted to advertising the life as 50,000 hours, which may be more realistic in the real world. Of course voltage controllers, essentially variable DC-DC chips, are so cheap now that it doesn’t make sense to not use one and with tighter voltage control a 100,000 hour rating might become realistic.

Back in the day, when red LED’s were new but just became cheap and the LED controller chip was brand new we used to solder up blinkers directly to a set of batteries. A local electronics shop would spring for a thousand of those ICs at $.20 each and sell them for $.50. Forty cents for a set of batteries and a some scrap telephone hookup wire and with a little soldering you could have a blinking set of LEDs for milk money. To save money and time we wouldn’t even buy a switch. Just solder them on hot and let them go. As I remember it a set of ‘heavy-duty’ chloride D-cells would run a pair of standard red LEDs for about a year. Alkaline would run them for most of two years.

@lorn: I think you mean the Centennial Bulb in Livermore, CA. it still burns, and even has a webcam:

http://www.centennialbulb.org/cam.htm

The problem with undervoltage is that the efficiency of the lamp is miserable. A normal incandecent lamps at its nominal voltage runs only around 5%. At lower voltage the filament is cooler, lasts longer, and emits only reddish light that the human eye is not adapted for. Truly a Light Emitting Resistor, as lpetrich called it above (#6).

I’m pretty sure these have been in use for at least 20 years already in fairly mundane applications. I’ve seen blue LEDs lighting the undersides of cars, and multi-color LEDs that can project several colors, or white light, by altering which diodes are emitting. Some of the more sophisticated ones have multiple LEDs of different colors, and can pretty much project any color of the rainbow. 🙂

One sentence of the quote from washingtonpost.com is misleading at best. It reads:

“Red, blue, and green light combine to make the bright white produced by LED lightbulbs.”

LED TVs yes. Unless LED usage is only for a back light.

For light bulbs, blue LEDs excite a phosphor making the desired white light. Different phosphors produce different color temperatures. I know for sure that’s what is done by lumenLED.net products. And I strongly suspect that most of the current crop of LED lighting products do it the same way.

You’re on the wrong track. For LEDs you should control current, not voltage.

This is generally true. Most commercially available “white” LED lamps are a blue LED with a yellow phosphor. Rarely you will find a device with separately addressable colored LEDs, sp that the color can be changed. An example is the Philips Hue lamp. These will be called “RGB” devices rather than “white.”

I believe some of the higher-cost LED light bulbs also include red LED chips along with the blue, because the phosphors tend not to fill in the long wavelength end of the spectrum very well. Look up “Color Rendering Index” for more.

Also, Reginald @13: Sure, you can get a Philips Hue, but what you really want is a couple dozen Elation Rayzor Q7‘s. Or at least, you would if you were the lighting designer for a rock band. Speaking of which….

I got some X-ray goggles and an X-ray gun,

I didn’t see a thing, but I sure was stunned

When I lost my money

To the back of a magazine.

What I really want is Cree XLamp LEDs in white and various colours, with PWM dimming controlled through a Raspberry Pi. But enough about me.