My first visit to Lake O’Hara, seventeen years ago, was not well timed.

On the afternoon of the first day, I spotted a well-trodden hiking trail leading up to Wiwaxy Peaks that seemed safe enough. On my way up, I passed by the person who had made the recent tracks, an employee who jogged up to the col and back as part of their daily routine. When I myself got up there, I spent a long time soaking in the most beautiful mountain vista I’d seen to date… with periodic glances to my left, towards some footprints that led into Oesa Valley. I was tempted to follow those as well, but the ranger had been forbidden us from hiking into that valley. The reason why would reveal itself, when an avalanche swept over that trail and billowed into Oesa Valley. I packed up my gear, and headed back down the way I came up.

As if to underscore the danger, when I rejoined the rest of the group we could hear avalanches thundering around the O’Hara valley, typically with ten seconds between them. That day remains the closest I’ve ever gotten to an avalanche (half a kilometre), as well as the most avalanches I’ve heard in an hour. So why would a bunch of photographers with no avalanche training gleefully walk into such a dangerous location?

That same evening, a dozen cameras were pointed in a dozen different directions as the warm glow of the setting sun danced around the valley. A century ago, the meadow we were standing in would have been standing-room only, with every square metre occupied by the tents of tourists eager to marvel at the same mountains. Parks Canada was forced to to block off the access road and place a hard limit of about four dozen people in the Lake O’Hara valley, just to ensure the place isn’t trampled flat. Naturally, the restrictions have only made the area more coveted.

While wandering around the path between Lakes O’Hara and Mary, before my trip up towards Wiwaxy Peaks, we noticed an odd lack of branches on lower parts of the pine trees. One of us realized that marked the winter snow line, which implied it could get as deep as some of us were tall. That shouldn’t have been surprising, Lake O’Hara is roughly two kilometres above sea level and within a few kilometres of the Continental Divide, so it’s effectively a high-elevation rain-forest. The spring melt was swelling the streams, so there were no shortage of waterfalls and wild flowers to take photos of in the safety of the valley.

Even in late June, over half of the O’Hara Valley was too dangerous to visit. And not one member of our group complained.

Well, OK, I’ll admit that by the third day I was grumbling a bit. So with the help of an employee I tracked down another mid-elevation viewpoint of the valley. All Soul’s Prospect was opposite to Wiwaxy Peaks, and the now-chill temperatures would slow the melt that lubricated those avalanches. If I was careful, and promised not to traverse beyond the Prospect, I should be safe. The start of the path was comfortably muddy, but as I ascended past Schaffer Lake I began walking over snow patches, then stepping up through ankle-deep snow. The snow was still patchy, though, and like on Wiwaxy someone else had left their footprints behind to point the way. It was not long until I’d reached my goal.

While soaking in the magnificent panorama at the Prospect, though, I was stabbed in the heart by my brain: was I doomed to be alone in the mountains?

After jogging six days a week for at least half a decade, I had been granted unlimited stamina. I figure my cardiovascular system was in the top 0.1% of humanity. But that carried a price: the group always travels at the pace of the slowest member, and even among fellow hikers I was never the slowest. Experience taught me that two kilometres per hour is average for a group, but when solo I could easily hit three and sometimes come close to four. This also placed restrictions on what trips I could pull off when I was with a group. I was condemned to putter along, putting on a happy face for everyone else but often wishing I could break into a jog.

Worse, unlimited stamina only means unlimited stamina. That employee jogging up to the Wiwaxy Peaks col managed it in half an hour, whereas I had taken two full hours. I did not have powerful leg muscles, nor extensive scrambling experience, nor a locker full of cross-country skiing gear; when I did run across someone who could keep up with or even pass me, we were usually mismatched in other ways. I had over-specialized and locked myself into a niche few others occupied.

The view from below Wiwaxy Peaks offered a satisfying solitude, but the Prospect felt painfully lonely.

Of all the papers I’ve read about loneliness, this remains my favourite:

Stephanie Cacioppo et al., “Loneliness: Clinical Import and Interventions,” Perspectives on Psychological Science 10, no. 2 (2015): 238–49.

Whereas the last paper I discussed took a skeptical angle, this one is much more straightforward. What is loneliness, and what can be done about it? This paper was my first introduction to the possibility that there are different types of loneliness.

Intimate loneliness, or what Weiss (1973) termed emotional loneliness, refers to the perceived absence of a significant someone (e.g., a spouse), that is, a person one can rely on for emotional support during crises, who provides mutual assistance, and who affirms one’s value as a person. …

The second dimension is relational loneliness, or what Weiss (1973) termed social loneliness. It refers to the perceived presence/absence of quality friendships or family connections, that is, connections from the “sympathy group” (…) within one’s relational space. According to Dunbar the “sympathy group” can include among 15 and 50 people and comprises core social partners whom we see regularly and from whom we can obtain high-cost instrumental support (e.g. loans, help with projects, child care; …).

The third dimension is collective loneliness, an aspect that Weiss (1973) did not identify in his qualitative studies. Collective loneliness refers to a person’s valued social identities or “active network” (e.g., group, school, team, or national identity) wherein an individual can connect to similar others at a distance in the collective space. As such, this dimension may correspond to what Dunbar (2014) described as the outermost social layer, which can include among 150 and 1500 people (the “active network”) who can provide with information through weak ties (Granovetter, 1973), as well as low-cost support (Dunbar, 2014).

Cacioppo (2015)

It was also my first introduction to the “social cognition” model of loneliness.

According to this model, lonely individuals typically do not voluntarily become lonely; rather, they “find themselves” on one edge of the continuum of social connections (…) and feeling desperately isolated (…). The perception that one is socially on the edge and isolated from others increases the motive for self-preservation. This, then, increases the motivation to connect with others but also increases an implicit hyper-vigilance for social threats, which then can introduce attentional, confirmatory, and memory biases. Given the effects of attention and expectation on anticipated social interactions, behavioral confirmation processes then can incline an individual who feels isolated to have or to place more import on negative social interactions, which if unchecked can reinforce withdrawal, negativity, and feelings of loneliness (…). This model points to a number of sources of dysfunctional and irrational beliefs, false expectations and attributions, and self-defeating thoughts and interpersonal interactions on which interventions might be designed to operate.

Ibid.

I’m not a fan of this view, it comes dangerously close to blaming lonely people for becoming lonely. Which is unfortunate for me.

Contrary to the conclusion of previous narrative reviews carried out since the 1980s, Masi et al.’s (2011) quantitative literature review revealed little evidence for better efficacy of one-to-one individual therapies compared to group therapies. … Twenty studies met the criteria for randomized group comparison design, and all four primary types of interventions known to reduce loneliness were present in this group. These four primary types of intervention programs were (a) those that increased opportunities for social contact (e.g., social recreation intervention), (b) those that enhanced social support (e.g., through mentoring programs, Buddy-care program, conference calls), (c) those that focused on social skills (e.g., speaking on the phone, giving and receiving compliments, enhancing nonverbal communication skills), and (d) those that addressed maladaptive social cognition (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy). Among these four types, interventions designed to address maladaptive social cognition were associated with the largest effect size (mean effect size = −.598).

Ibid.

If loneliness were just a simple matter of interpersonal relationships, cognitive behaviour therapy shouldn’t have much effect. And yet it instead seems to be the most effective tool for dealing with loneliness, which is compatible with the problem being the lonely person.

But it’s also compatible with loneliness being subjective. You can wander into the wilderness on a solo trip, and yet not feel alone; you can wander in with a group, and yet be hit with a profound sense of loneliness. This paper defines loneliness as “a discrepancy between an individual’s preferred and actual social relations” which “leads to the negative experience of feeling alone and/or the distress and dysphoria of feeling socially isolated.” One way to resolve that is to develop those social relations, but that takes substantial time and effort, as well as society you’d like to relate to that would also like to relate back.

As comedian Robin Williams said: “I used to think the worst thing in life was to end up all alone. It’s not. The worst thing in life is to end up with people who make you feel all alone” (2009).

Ibid.

Another way is to change your preferences, to become more comfortable with fewer or less active social relationships. A third is to defuse the dysphoria of isolation, by challenging the thoughts that are causing you pain. Unlike the first, these two only require one person in the room and thus aren’t dependent on chance and circumstance. And while the second way looks suspiciously like conversion therapy, the third sounds an awful lot like cognitive behavioural therapy.

This is where I can slip free from the “social cognition” model: some people may possess dysfunctional beliefs that encourage loneliness, true, but even those that don’t could still feel better after de-fanging their inner critic. My beef isn’t that the model is wrong, it’s that when it becomes prescriptive it is dangerous. If you start off assuming those dysfunctional beliefs exist, then you might gaslight them into existence or argue someone cannot be lonely because they don’t have those beliefs.

Interventions designed to enhance social support produced a significant but small reduction in loneliness (mean effect size = −.162), while interventions to increase opportunities for social interaction (mean effect size = −.062, n.s.) and interventions to improve social skills (mean effect size = −.017, n.s.) were not found to be effective in lowering loneliness. These findings reinforce the notion that interpersonal contact or communication per se is not sufficient to address chronic loneliness in the general population.

Ibid.

If we exclude pharmacological treatments, for the good reason that none have been approved for human use, we’re left to conclude that group cognitive behavioural therapy sessions are the best cure. Social and support groups don’t help, nor does chatting one-on-one with someone.

Or at least, we’re left to conclude that from a single meta-analysis conducted in 2015. Surely more research has been done on the subject?

Paul G. Shekelle et al., “Interventions to Reduce Loneliness in Community-Living Older Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 39, no. 6 (2024): 1015–28.

N. Morrish et al., “What Works in Interventions Targeting Loneliness: A Systematic Review of Intervention Characteristics,” BMC Public Health 23, no. 1 (2023): 2214.

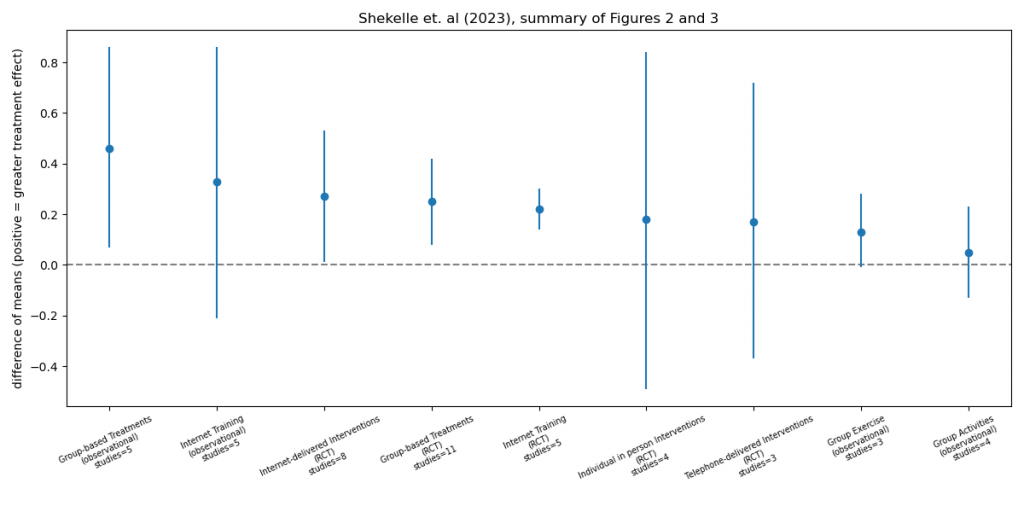

That first review article isn’t as universal as I’d like, but conversely it spans papers published between 2011 to 2023 so there’s little overlap with my favourite study. I can also summarize it in one chart.

One interesting wrinkle is the introduction of internet-related solutions. “Internet interventions” refers to delivering some sort of therapy via the internet, for instance three of those eight studies used cognitive behaviour therapy, so it’s no surprise that helps. “Internet training” is much more puzzling, as it refers to training on “basic computer skills, internet use, email competency, … social media, photographs, and video chat applications.” Still, this does vastly increase the pool of potential people to add to your collective or even relational network, and because the costs of creating or destroying online friendships are so low relative to their in-person equivalent, seniors can satisfy their loneliness by collecting more high-quality friendships.

The relative success of both internet-related solutions argues against placing too much emphasis on in-person contact. Indirect communication, via text, speech, or video, can still help relieve loneliness. One interesting consequence is that “going outside to touch grass” is not necessarily a good thing.

The second review article is only a minor advance over my favourite study.

Group sessions appeared preferred, however the importance of a person-tailored approach to delivery was also recognised by several included studies. This review also revealed the importance of interaction, particularly through active participation and group or facilitator contact, both during and between sessions. Finally of note, this review found value in considering the intervention period, in particular sustained contact following the conclusion of the intervention to maintain effectiveness. It suggests there is not a ‘quick fix’ to loneliness, but that learnt practices and behaviour should be built into one’s lifestyle to achieve longevity of reduction in loneliness. This was consistent with the observation that aiming to improve

friendship or community connection was associated with positive intervention outcomes.Morrish et al. (2023)

Again, some sort of group therapy with a trained facilitator seems best. The emphasis on long-term interventions is somewhat novel, and unlike Shekelle et al. there’s a clear skew towards in-person interaction. That may be because seniors don’t take much advantage of online interaction, relative to the general public, so they have more to gain.

While it’s nice to get confirmation of prior research, there’s an interesting detail buried in this study.

Three studies concluded there to be no decrease in loneliness as a result of the intervention, thus were considered ineffective … These interventions aimed to reduce loneliness through social support and technology use (n = 1), a Good Neighbour Program (n = 1), and introducing Embodied Conversational Agents (computer generated humans) (n = 1). These ineffective interventions were delivered online (n = 2) or by phone (n = 1).

Ibid.

“Embodied Conversational Agents?” Large language models have just entered the chat.

I could have sworn that snowshoe trip to Opal Falls happened before this visit to Lake O’Hara, and that my right snowshoe was the one that broke, but the opposite was true for both. The way your memories shift and distort to conform to your current biases is kind of fascinating. Why, for instance, was I wearing my cross-country skiing boots on the Opal Falls trip? That’s a terrible choice. Nowadays, I would have worn sandals instead.

Typing up this trip to O’Hara also revealed how much my memory of the landmarks had degraded. I completely forgot the name of Yukness Mountain, and I had removed the plural from Wiwaxy Peaks. “All Soul’s Prospect” had become “All Soul’s Point”, though to be fair I’m pretty sure I was making the same mistake decades ago. Thank goodness this was a photography trip, so I have a record of what I saw from the Wiwaxy Peaks col.

I do feel bad about spamming all those names at you, so I flexed my HTML knowledge a bit; hover your mouse over the above image, and you’ll get the names of almost all the major landmarks plus a few minor ones. If that somehow breaks, here’s a direct link to the annotations. In addition, a “col” is the lowest point of a mountain ridge connecting two peaks, plus Schaffer Lake, Odaray Mountain, and Cathedral Mountain are out of sight on the right.

Another oddity about this trip: I took a lot of selfies. I’m notorious for never taking self-portraits, but apparently I only imposed that rule sometime after this trip. Maybe reviewing the lonely selfies from this trip led to that policy? Or maybe it was a natural outgrowth of consistently leaving my tripod at home? My tripod wasn’t with me on that trip to All Soul’s Prospect, so I struggled to level my camera when trying to shoot some selfies.

Hungabee Mountain is behind my head, a bit of Mount Biddle is opposite, Opabin Plateau stretches out behind me, and just below the branding on my track pants is a tiny sliver of a frozen Opabin Lake. Even after a bit of correction, I still look as tilted as I felt in the moment, seventeen years ago.