On this Memorial Day, I’m going to have to have a discussion with my spiders about their distinguished, noble ancestry. It was kind of Nature to publish a study of their many-times-great grand uncles, an ancient euchelicerate named Setapedites abundantis, a common fossil found in Moroccan sediments that are about 478 million years old, which puts it right in the middle of the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event, a key moment in the evolution of modern taxa.

This is not a spider, though. It belongs in the euchelicerata, the large systematic group that includes spiders, scorpions, ticks, horseshoe crabs, sea scorpions, and other extinct groups. As you might guess from the name, a key feature is the presence of chelicerae, anterior appendages that in spiders carry the venomous fangs. It also has a common feature we see in both spiders and horseshoe crabs, the fusion of the anterior segments to form a prosoma, with posterior segments forming the abdomen or opisthosoma.

While it’s a cool looking little dude, it’s marine and pretty remote from modern chelicerates. From the dorsal side, it looks like an undistinguished little crustacean, of a type that was probably swarming in Ordovician seas.

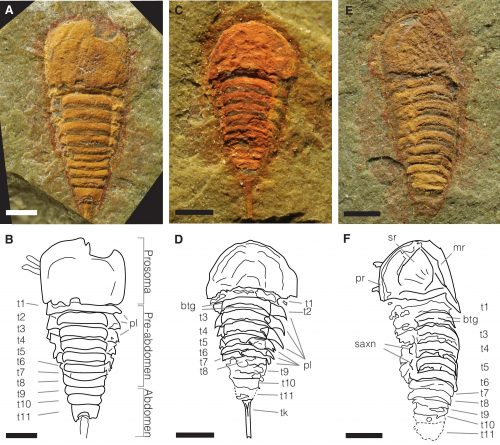

A, B MGL.102899 and interpretative drawing, articulated specimen in dorsal view. C, D MGL.102828 and interpretative drawing, articulated specimen in dorsal view. E, F MGL. 102872 and interpretative drawing, articulated specimen in dorsal view. Abbreviations: btg, bipartite tergites; mr, median ridge; pl, pleura; pr, prosomal rim; saxn, sub-axial node; sr, sunken region; t1–11, tergites 1–11; t, telson; tk, telson keel. Scale bars, (A–F) 1 mm.

Where it gets interesting is when it’s flipped over, and you get a glimpse of the mass of limbs.

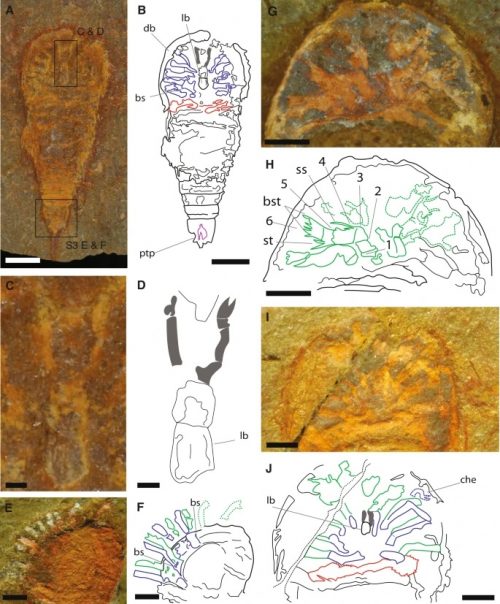

A, B YPM IP 517932c and interpretative drawing (counterpart), articulated specimen in ventral view. C, D YPM IP 517932c and interpretative drawing, chelicerae, and labrum anatomy detail. E, F Close-up of the prosoma of MGL.102934 and interpretative drawing, in dorso-lateral view. G, H Close-up of the prosoma of MGL.102634 and interpretative drawing, in ventral view. I, J Close-up of the prosoma of MGL.102800a under alcohol and polarized lighting, and interpretative drawing, in ventral view. Abbreviations: 1–6, podomeres 1–6 of the exopod; ptp, pretelsonic process; bs, basipodite; bst, brush-like setae; che, chelate podomere; db, doublure; lb, labrum; ss, single setae; st, pair of setae. Chelicerae are highlighted in gray, endopods in blue, exopods in green, opisthosomal appendages in red, and the pretelsonic process in purple. Scale bars, (A, B) 1 mm; (C, D) 100 µm; (E–K) 500 µm.

In front of the jaws proper (labrum, lb) it has a pair of small chelicerae (che). These have since evolved into the massive, sharptoothed chompers you can see my tarantula using to turn a mealworm into macerated mush.

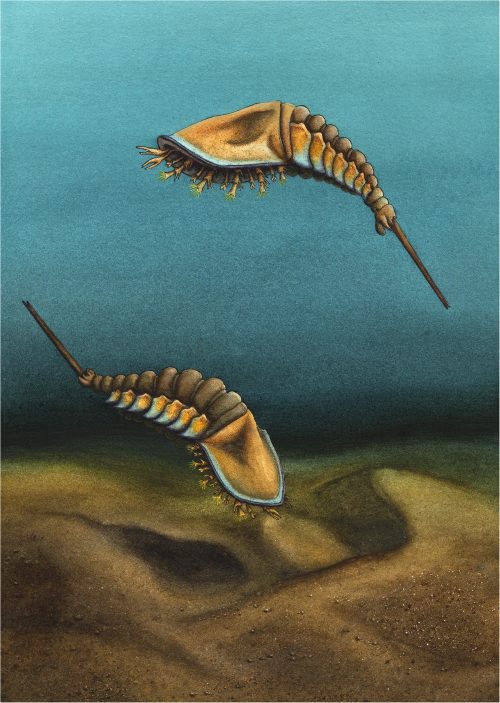

Setapedites wasn’t such a fierce predator. Here’s what it looked like.

Cute, right? I don’t know why it’s drawn as a swimmer, though — with that anatomy, it looks more like a benthic organism.

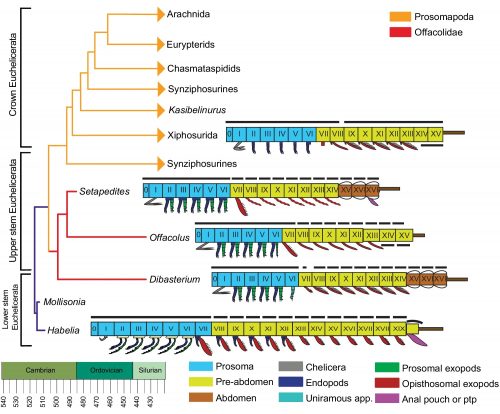

The final bit of interesting information is that they mapped out the correspondences in the segmentation of this animal with other, similar fossils and the extant Xiphosurians.

Simplified extended majority rule tree of a Bayesian analysis chronogram of euchelicerate relationships, based on a matrix of 39 taxa and 114 discrete characters, showing the position of Setapedites abundantis within Offacolidae. Lineages extending after the Silurian are indicated with arrowheads. Schematic models of the body organization in Habelia, Setapedites abundantis, Dibasterium, Offacolus, and Xiphosurida illustrate the origin and early evolution of euchelicerate uniramous prosomal appendages and tagmosis. Roman numbers designate somites. Prosoma somites are highlighted in blue, pre-abdomen somites in yellow, abdomen somites in brown, and the possible anal pouch or post-ventral structure (pvs) in purple. Black dorsal lines indicate tergites and cephalotorax. Schematic model of Xiphosurida Offacolus, and Dibasterium from 45, Habelia

Also of note: Setapedites had biramous appendages, a feature that is mostly kind of lost in modern arthropods — the outer branch got adapted into gills and lungs and even wings.

I can’t help but notice that domestication and artificial selection turns wolves in little yapping Pomeranians, but natural selection turns shrimp into tarantulas.

By coincidence, Ms. KG and I had to remove a member of the euchelicerata from our dog’s neck yesterday, using a special tool bought for the purpose (it’s supposed to avoid leaving the tick’s mouthparts in the skin, and causing it to expel blood back into the host, both of which can cause infection). So I’m not feeling particularly positive about the subphylum at present!

Ticks are the unseemly reprobates of the otherwise gentlemanly arachnid family. Those of us who love spiders never invite ticks to our dinner parties.

Ticks: almost as bad as Trumpists and Tories!

To be fair, natural selection also turned coelurosaurs into pigeons.

I just spent 10 minutes in the garden looking for a pair of beloved Felcos my partner lost yesterday, my pants and shoes sprayed with tick repellent. After finding her Felcos, I came in, sat down and found a tick on my leg almost immediately. Now the tick bathes in alcohol and my clothes are in the dryer.

Ticks are a problem here in Marin county this year, probably thanks to the rain. The grass is tall and they apparently love the tall grasses.

The spiders, on the other hand, are most welcome in our house and garden.

adipicacid — Like pigeons…ring-necked doves to be specific here…I would add Canada geese to the suggestion of natural selection gone awry.

The aquatic arthropods who became spiders and those who became insects colonised land independently, which means the land must have become habitable relatively quickly once plants got a foothold – if it was a drawn-out process the group that tolerated the new conditions best would have had

time to hog mist or all the ecological niches.

What a beautiful fossil! It’s delightful to see ones with so much detail.

Thank you PZ.

Very neat and fascinating fossil find here!

The carboniferous arachnid too.

And dinosaurs into Tweety Pie.

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-dinosaurs-shrank-and-became-birds/