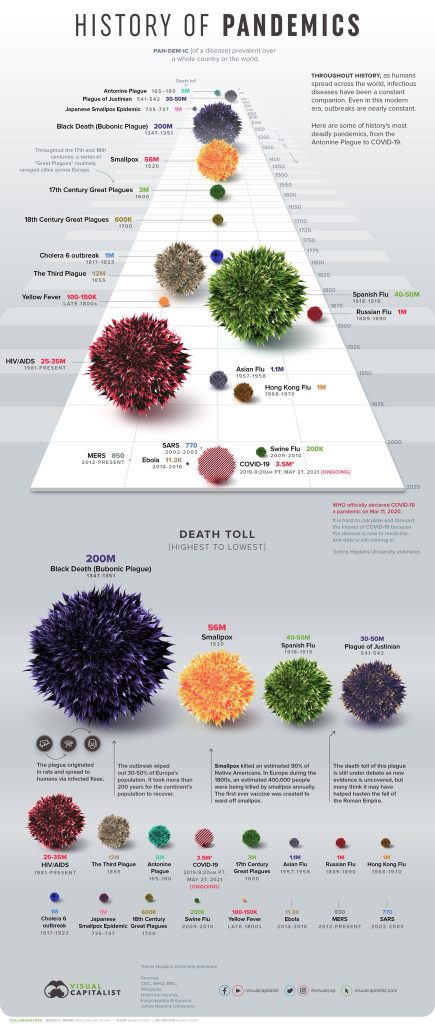

Here’s an interesting chart (although, portraying pandemics as spiky spheres is a bad choice — people are not good at visualizing relative volumes, and putting those volumes in a perspective that reduces the size of older one is a terrible idea) showing various afflictions on the human species over time.

The Black Death was the big one, but look at HIV — it’s amazing how our culture diminished the significance of that one, pretending it wasn’t happening even as its victims were dying in hospitals, and as prominent figures fell to it.

Smallpox coulda been a contender for the biggest plague of them all, but humans invented something that stopped it in its tracks: vaccination. If only people recognized the importance of that today…

A rather pointless presentation, it needs correction for population. The world human population has far more than doubled within my lifetime, and the total number of humans at the time of the Black Death was probably well under a billion, so at least a fifth of the population succumbed. That would be equivalent to over 2 billion today, and that spiky globe would dwarf most of the others.

Also, where’s malaria?

I think the representation of the devastation of the indigenous populations of the America’s is rather lacking.

Where is tuberculosis, the white plague?

Where is hepatitis B?

CDC/WHO: Hepatitis B: Approximately 2 billion people are infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV), making it the most common infectious disease in the world today. Over 350 million of those infected never rid themselves of the infection.

Tuberculosis: Tuberculosis causes nearly 2 million deaths every year, and WHO estimates that nearly 1 billion people will be infected between 2000 and 2020 if more effective preventive procedures are not adopted.

Bruce fuentes @ 3 beat me to it.

The devastation in the Americas was so extraordinary that as paleo-DNA tecnologies became available, it turned out that the populations of indians in parts of North America have ZERO extant descendants. In some places, the European diseases literally exterminated the population.

The basic idea of this graphic is great, but the execution is poor. Apart from the perspective problem you’ve already mentioned, it’s also completely inconsistent in terms of time-frames. The Black Death is weighted by its estimated total death toll while smallpox is weighted by one particularly bad year (and closer reading shows it isn’t even one year, it is an estimate of the smallpox death rate among American Indians, which certainly wasn’t done and dusted by 1520!). If you throw in the fact that smallpox has been with humans for almost as long as recorded history, killing millions of people year after year and the only widely used and effective bioweapon, it is by far and away the worst pathogen on that chart.

I get that the graph was only looking at big pandemic events — but smallpox has essentially been a running human pandemic since 1500 BC, possibly even earlier. Picking out two specific smallpox events (the Japanese epidemic of 735-7 and the smallpox explosion in the Americas) massively underreports its burden.

Also, the Plague of Justinian did little to hasten the end of the Roman Empire. The empire lasted another 1000 years after the plague and more importantly the Byzantine domain reached its peak with the Western reconquest and the 50-year peace treaty with Persia after the plague had ended. For sure the plague didn’t help. It weakened the Western defences when challenged by the relatively-unscathed Lombards, but the thing that really killed the Byzantine Empire was the short-sighted internal power politicking that only occasional emperors were capable of suppressing. (Justinian was not actually a particularly good emperor, but he had the fortune to marry Theodora and have Belisarius working for him). The empire also had a major renaissance under Basil II four centuries later, reconquering almost all of the Eastern Empire and making inroads into the West before his death led the empire to start splintering again. (Whatever qualms one might have about Justinian pale beside Basil II, who managed to hold the empire together by being a thoroughly vicious bastard.) Again, this was long, long after the Justinian Plague had ended.

And finally, as you say, where’s malaria? It kills 1-3 million people every single year and has been parasitising vertebrates since before humans or even primates existed. In terms of sheer impact it is probably the worst pathogen in human history. (Smallpox is its only serious rival.)

Wikipedia on the Third Plague (citation numbers removed):

Malaria doesn’t show up as a epidemic that blows up over a wide area and then ebbs; instead it’s just constantly there until you kill the mosquitoes. So it’s not included in the history of pandemics.

If you add all those ‘Plagues’ together…

Yersinia pestis is one nasty critter still sitting there on the sidelines, bidding its time until an apocalyptic combination of favorable mutation, antibiotic resistance gene transfer, hosts, and the ineffectual behavior of an arrogant self-entitled population unleashes it.

Science may be able to save us on that day, but I doubt society will allow it to.

The Human race has spent the last few thousand years inventing even better ways of bumping each other off ,but compared to all

the nasties in nature ,we are just weeing in the wind.

So this chart was produced by Visual Capitalist. I’m not particularly dogmatic on the subject of capitalism, but I do feel a particular rant coming on about infographics. Trying to hold back.

Bruce Fuentes @ 3

Not only the Americas native populations but pretty much every place the European explorers reached. The South Pacific islanders were devastated by small pox as well as other diseases like syphlis.

#5

Throughout white, American history we have downplayed the utter destruction of indigenous people. There was somewhere between 75 and 200 million indigenous people in the Americas at first contact with the Europeans. Over 95% of that population was gone by 1600. The only reason some of the native people seemed savage like is because their societies completely collapsed due to the magnitudes of the deaths.

#12

Agreed. I was being a bit American-centric there. Not to downplay the devastation of the Pacific Islanders, but we are talking probably around 100 million people in the Americas.

@9

unfortunately I have to agree with you on all points. It looks like the disease of civilization patiently waiting for the next time circumstances are in line. It is not if but when. with the interconnected nature of humans today it should be memorable

uncle frogy

dorght @9 and Uncle froggy @14:

There are a couple of things keeping plague from coming back as a pandemic (since it could whenever it wants, it’s all over the Western US, among other places).

First are changes to hygiene in much of the developed world. There is now a hypothesis that plague was spread both by fleas and by human body lice (a separate and distinct species from human head lice, which doesn’t seem to carry plague) and human body lice are much, much, much less common than they used to be. So that significantly cuts down on the rate of spread.

Second are changes to housing. Again, this is mostly focused on the developed world, but when was the last time you had a rat in your house? Or more than one or two mice? Modern (and modern goes back quite a ways) homes are built to keep pests (rodents and insects) out. If the rats aren’t getting in, they’re not sharing their fleas.

These things are already in place and not likely to change without some kind of outside catastrophe (the re-emergence of plague is a common theme in post-apocalyptic fiction), so even in our complacency we are not increasing the risk.

@15 JustaTech

You are discounting the prevalence of cats in households. A known transmitter of pneumonic plague to humans. Dogs not so much. Yet.

But yes, there are good obstacles to pandemic in modern society. There are, however, countless experiments being done by nature every day for years, decades, centuries.

@15

very true I live in a very old part of town in a house that is over a 100 years old and until the alley cat population grew to the number it has today there were plenty of rats and mice enough that I could see mice in daylight on occasion. I guess one of the things that saves me along with modern sanitary practices, is the distance I am from the outskirts of “the city” which also tends to isolate me from rabies as well which is also endemic in the west.

the thing that I think is important to remember as you pointed out it is our behavior collectively that is the biggest determinate factor. Yersinia pestis is not a novel bacteria the out brakes are to a large part determined by our behavior. I would also say that many (all?) the pandemics can be traced to how we respond and contribute to their spread.

case in point the spread of the current virus regardless of the ultimate source.

numerobis@8–

You’re absolutely right, but if they’d meant to stick to a precise definition of pandemic then the authors should really have left the West African Ebola outbreak of 2013-16 off entirely.

What if there was an outbreak of a disease that uses dogs or cats as a vector to humans. Are we all doomed?

I can’t see people giving up their pets even as a mandatory control measure. Until of course the pets become sick then the fear strikes and the harbored pet is ejected from the household to spread the disease even more.

Wasn’t this a factor in one of the Planet of the Apes movies?

I await the re-emergence of therapeutic bacteriophages. They were tried before antibiotics came to prominence. Taking antibiotics is like setting mousetraps; taking a bacteriophage is like getting a cat. (Or, PZ, if you prefer: taking antibiotics is like setting glue traps; taking a bacteriophage is like getting a spider.) Bacteriophages are more specific ( = less general ) than antibiotics; and while bacteria can out-evolve an antibiotic, bacteriophages evolve faster than them.

mRNA vaccination has proved its worth. There’s nothing like a plague, a war, or a natural disaster to advanced the art of medicine. Future plagues, and they’re coming, will inspire other biomedical revolutions.

I speculate that the humans of the far future will be superhuman in their disease resistance, self-healing, strength, dexterity, sensoria, intelligence, empathy, and wisdom; that’s the good news; but the bad news is that they’ll need those superhuman abilities in order to survive long enough to reproduce.

The Yamnaya steppe people had some exposure to yersina pestis [the marmots are a reservoir for the pathogen] so they had somewhat lower mortality than the neolithic/early bronze age European farmers. When the yamnaya moved west they brought the pathogen, and it started killing off the ‘aboriginal’ europeans like the european diseases would kill indians.

.

I always wondered how the organised Stonehenge-era English polity could allow the indo-europeans to cross the channel.

The answer is, the local polity was trashed before the indo-europeans arrived in larger numbers. The immigrants then adopted parts of the local culture, like the megalith tradition.

Ah, the great 1990s Koosh ball plague.

(I’m just the right age to remember those hairy rubber ball toys.)

Probably a few months ago – they might still be visiting, but we haven’t heard scrabbling in the walls for a while, and the dog is no longer sniffing and scratching in various corners. While they were here, they ate their way through several packets of oats stored in the loft. It’s an oldish house (1880s), but we don’t know how they got in – most likely up a drainpipe and then squeezing under the eaves. According to some experts we consulted, the closing of city centre restaurants and bars led many a promising young rat to bundle up his possessions in a red-spotted handkerchief tied to a stick, and set off to seek his fortune in the suburbs!