I’m trying to raise money for the The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, and I promised to do a few things if we reached certain goals. I said I’d write a post microRNAs and cancer if you raised $7500. And you did, so I did. I kept my clothes on this time, though, so here’s a more serious picture of yours truly: this is what my students see, which is slightly less terrifying, nicht wahr?

If you want more, go to my Light the Night fundraising page and throw money at it. If we reach our goal of $10,000, I’ll organize a Google+ Hangout to talk about cancer. Note that we’re also getting matching funds from the Todd Stiefel Foundation, so join in, it’s a good deal.

It’s all epigenetics. Now I’ve gone and done it: I’ve used the “e” word, epigenetics. Nothing seems to fire off well-meaning misconceptions from otherwise sensible pro-science folks than epigenetics — it’s a major new revolution in evolution! It changes everything! It’s a way to get inheritance of acquired characteristics!

Nope.

Epigenetics is routine and has been taken for granted by cell biologists for at least 6 decades. It is simply a principle of gene regulation — switching genes off and on — that persists over multiple cell generations. You aren’t surprised that when liver cells divide, they produce more liver cells, are you? They’ve simply inherited transcription factors and patterns of modification of DNA from their parent cell that restricts their cell fates. There are also patterns of gene expression induced in gametes within parents that modulate initial patterns of gene expression in the fertilized zygote — that is, the state of the parental cells affects the state of the embryo’s cells — which is exactly what you’d expect.

What seems to set people off is that it is an effect of the environment on the state of the genome, and there is this bizarre bias floating around that that can’t happen. Of course it can! Every summer when you get a tan, every winter when you put on another five pounds, every time stress at work makes you prone to get sick…those are environmental factors influencing your biology.

In previous installments of this series, I told you about oncogenes, genes that when over-expressed or over-active switch on cellular processes (like proliferation) that promote cancer, and tumor suppressor genes, which protect against cancer, and which in cancers, are often found to be inactivated or down-regulated. Over-expressed? Down-regulated? That sounds like the sorts of things epigenetic changes can do.

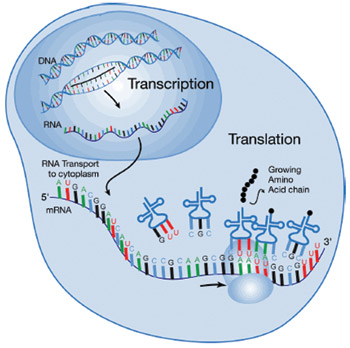

Further, here’s an interesting observation. Everyone knows the standard pathway: genes in DNA are transcribed into RNA which is then translated into protein. One might naively imagine, then, that the amount of RNA produced would be roughly correlated with the amount of protein produced. It’s not. In analyses of cancers, only 20% of the mRNAs involved showed any correlation between the quantity of mRNA and the quantity of protein — there is something else that is modulating either the amount of translation or the turnover of proteins in the cell, and the fact that 80% of the genes playing a role in cancer show such variation tells us that these kinds of regulatory effects are important.

There must be something stepping in and interfering somewhere between transcription of the gene into messenger RNA, and translation of messenger RNA into protein. One of the somethings is microRNA.

These are tiny little snippets of RNA, typically 22 nucleotides long, that have complementary sequences to their target gene mRNA — they bind to matching RNAs and inhibit translation. Thousands of these microRNAs have been discovered in the last few years, and they’ve also been found to play important roles in regulating gene expression in blood cell lineages, brain activity, insulin secretion, and fat cell development…and in cancer.

As you might guess from the previous articles in this series, there are obvious ways microRNAs could promote cancers. A microRNA that blocks tumor suppressor genes from being expressed could be modified to be produced at a higher level, or a microRNA that would hamper an oncogene’s activity could be mutated to be unable to recognize its target. Easy! Simple! Well, except that this is biology, and nothing is simple in biology (trust me, if you don’t enjoy problems blowing up in your face and getting harder and harder, don’t become a biologist.)

One reason this is complicated is that there are so many details to be worked out — swarms of microRNAs are involved, we don’t know the majority of them, and we don’t know what we’ll learn as we discover more. As Weinberg says,

…the discovery of hundreds of distinct regulatory microRNAs has already led to profound changes in our under- standing of the genetic control mechanisms that operate in health and disease. By now dozens of microRNAs have been implicated in various tumor phenotypes, and yet these only scratch the surface of the real complexity, as the functions of hundreds of microRNAs known to be present in our cells and altered in expression in different forms of cancer remain total mysteries. Here again, we are unclear as to whether future progress will cause fundamental shifts in our understanding of the pathogenetic mechanisms of cancer or only add detail to the elaborate regulatory circuits that have already been mapped out.

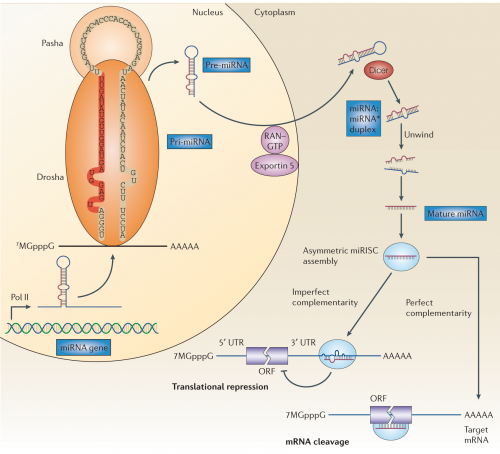

But also, we’ve learned that it’s not simply a matter of a few short bits of RNA getting transcribed and dumped into the cytoplasm — there is a whole elaborate cellular apparatus dedicated to microRNA processing. Behold!

Don’t panic, I’ll hold your hand and we’ll walk through it. miRNA genes are first transcribed into RNA by RNA polymerase II; notice that the transcript, which is called a pri-miRNA (or primary microRNA) contains some long stretches of internal complementarity, and that the RNA folds into a hairpin loop. This RNA is grabbed by an RNA binding protein, Pasha, and an RNA cutting enzyme, Drosha, which snips off some excess bits to produce a smaller stem-loop structure about 70 nucleotides long, which is partially double stranded RNA. It also gets a new name: Pre-miRNA. Pre-miRNA is then exported out of the nucleus and into the cytoplasm by a channel protein, Exportin-5.

Once in the cytoplasm, another RNA cutting enzyme, aptly named Dicer, snips off a few more bits to reduce it to two very roughly complementary RNA strands, now called the miRNA:miRNA* duplex. One of these strands is then loaded into a set of proteins to form the miRNA-associated multiprotein RNA-induced silencing complex, thankfully called miRISC for short.

The short, 22-nucleotide long strand of RNA in the miRISC is what gives it specificity — the miRISC proteins carry it along as a template to match against messenger RNAs they encounter. If the miRNA makes a perfect match to some unfortunate strand of messenger RNA, the miRISC cuts up the mRNA to destroy it. If it’s an imperfect match over just some significant fraction of the 22-nucleotide sequence, it it just locks up the RNA and represses its translation.

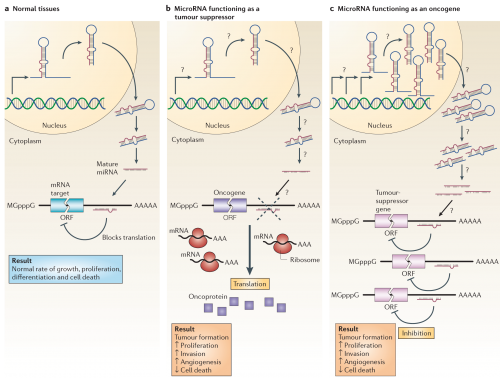

The way these can affect cancer is illustrated below. If a microRNA that inhibits an oncogene is mutated (b), that oncogene will increase the amount of protein produced from the available RNA; the oncogene could even be normal in sequence and function, and just the boost in its signal could contribute to tumorigenesis. Alternatively, a mutation in a microRNA gene that affects a tumor suppressor could amplify its production (c), producing a greater inhibition of a healthy gene that acts to prevent tumorigenesis.

MicroRNAs can function as tumour suppressors and oncogenes. a | In normal tissues, proper microRNA (miRNA) transcription, processing and binding to complementary sequences on the target mRNA results in the repression of target-gene expression through a block in protein translation or altered mRNA stability (not shown). The overall result is normal rates of cellular growth, proliferation, differentiation and cell death. b | The reduction or deletion of a miRNA that functions as a tumour suppressor leads to tumour formation. A reduction in or elimination of mature miRNA levels can occur because of defects at any stage of miRNA biogenesis (indicated by question marks) and ultimately leads to the inappropriate expression of the miRNA-target oncoprotein (purple squares). The overall outcome might involve increased proliferation, invasiveness or angiogenesis, decreased levels of apoptosis, or undifferentiated or de-differentiated tissue, ultimately leading to tumour formation. c | The amplification or overexpression of a miRNA that has an oncogenic role would also result in tumour formation. In this situation, increased amounts of a miRNA, which might be produced at inappropriate times or in the wrong tissues, would eliminate the expression of a miRNA-target tumour-suppressor gene (pink) and lead to cancer progression. Increased levels of mature miRNA might occur because of amplification of the miRNA gene, a constitutively active promoter, increased efficiency in miRNA processing or increased stability of the miRNA (indicated by question marks). ORF, open reading frame.

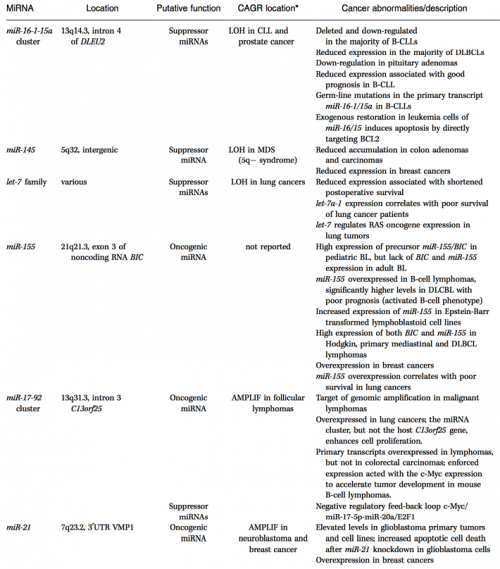

This is not simply a hypothetical possibility, either. Dozens of miRNA genes have been implicated in human cancers — they show abnormal variations in expression in specific cancers and also have known oncogene/tumor suppressor targets.

These microRNAs are a relatively new scientific phenomenon — they weren’t even a blip on the radar when I was a graduate student, and when I did start hearing about them in the 1990s, they were thought of as a weird mechanism found in highly derived nematodes. Now we’re seeing them everywhere, and beginning to recognize their importance in controlling all kinds of genes. The process of developing tools to control miRNAs is underway in the laboratory, but it has a long way to go before we have effective clinical tools to combat cancer with miRNAs or antagonists to miRNAs. At the very least, it’ll be another tool we can use.

Calin GA, Croce CM (2006) MicroRNA-cancer connection: the beginning of a new tale. Cancer Res. 66(15):7390-4.

Esquela-Kerscher A, Slack FJ (2006) Oncomirs – microRNAs with a role in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 6(4):259-69.

Hanahan D, Weinberg RA (2011) Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144(5):646-74.

Hmm. Interesting, especially in context of the recent article (or rather blurb) on a chemical that it intended to inhibit suppression of protein production, which is responsible for pretty much shutting down protein production entirely in brain cells, in reaction to the formation of abnormal proteins, be they prions, or the plaques produced in Alzheimer’s, and similar diseases. Taken together, it sounds like the, as of yet not a human version, drug may knock out these suppressors, preventing the cells from starving themselves to death (the presence of abnormal proteins apparently triggering shutdown in production of proteins, in a faulty attempt to suppress production of malformed proteins, unintentionally killing the cell instead). Ok. Can’t find the original article, but this other one suggests that one strategy is in fact knocking out the malformed protein itself, or even suppression/removal of proteins from the cell surface which are expressed, but “susceptible” to being bent all out of shape by the presence of said malformed protein, which is a bit different than targeting the promoter/suppressor miRNA… :p

http://christineadavis.com/wordpress/health/prion-proteins/

Definitely a complex mess. lol

Thanks PZ, this is a fascinating series.

How does this compare with non-cancerous cells?

You have an awesome beard – perhaps you have some quality microRNA strands in there for beard production instructions??? B]

Epigenetics has been accepted for 6 decades? Maybe by a small clique of cell biologists but not by the ‘mainstream’. My father was head of a department of zoology in an english university (he may even have taught you in Oregon) and, from personal experience I can say that any mention of the word was cause for ridicule.

Now I’m trying to think of what English professors taught me at the UO — Graham Hoyle? Michael Land? — but none of them were heads of a department of zoology.

Epigenetics is simply the inheritance of patterns of gene expression in multiple generations of cells. So yeah, it would be shocking if someone didn’t accept that in the last few decades.

Presence & absence of miRNA families has been used as a source of characters for phylogenetic analysis.

I think the term has been reserved for the inheritance of patterns of gene expression in multiple generations of “individuals”, as if individuals were magic in multicellular organisms. Wouldn’t be the first time that a tradition of inconsistent application of terminology misled people for decades.

Like… I’ve never encountered the word in any explanation of why the descendants of liver cells stay liver cells.

There is absolutely no difference between developmental transmission of patterns of gene expression in cell division and developmental transmission of patterns of gene expression between multicellular individuals. Gametes are just specialized cells like liver cells.

Biology is complicated!

Whenever I first mention to someone that I specialized in particle physics in school, about 50% of the time they give me this wide-eyed, cheeks-puffed expression, a “better you than me” face. I don’t understand it. I picked the easy field. There are only thirty things (or seventeen things and a symmetry relation, if you like), and one rule. Just accept that the nature of the universe is fundamentally different than you thought and do some multivariable differential equations and you’re all set.

Or does every field look sensical and unified from the inside perspective of an expert?

PZ – did you get to Coose Bay?

Coos Bay, you mean? The OIMB? I’ve been there a couple of times.

“(trust me, if you don’t enjoy problems blowing up in your face and getting harder and harder, don’t become a biologist.)”

This is actually why I decided not to go into biology professionally, although it was my favorite subject, and I still follow it avidly. It would drive me mad to do research in it.

“Or does every field look sensical and unified from the inside perspective of an expert?”

Nope. Biology doesn’t. Evolution and chemistry and physics provide some unifying basics (eyes need lenses to focus). But the thing about evolution is, it’s mainly driven by randomness (mutation and other gene-mixing, etc.), with what is really fairly mild selective pressure.

The result: no two things are going to be alike. Look at something which appears to be similar to something else, and it’ll turn out to be completely different “under the hood”. It’s the opposite of unified. It’s massive, massive variety. Variety everywhere.

I think biology is marvellous, but it is definitely not “sensical and unified”.

Not to that extent; but I, for one, prefer this complexity over doing “some multivariable differential equations”.

PZ

Well it’s about damn time a biology professor blogger steps up and says something non-reactionary and sensible about epigenetics. The ill-informed hate form the old guard is an embarrassment.

Topically, in the most recent edition of Development the authors of a paper say in an interview:

Inducible mouse models illuminate parameters influencing epigenetic inheritance

http://dev.biologists.org/content/140/4/843.long