The Probability Broach, chapter 9

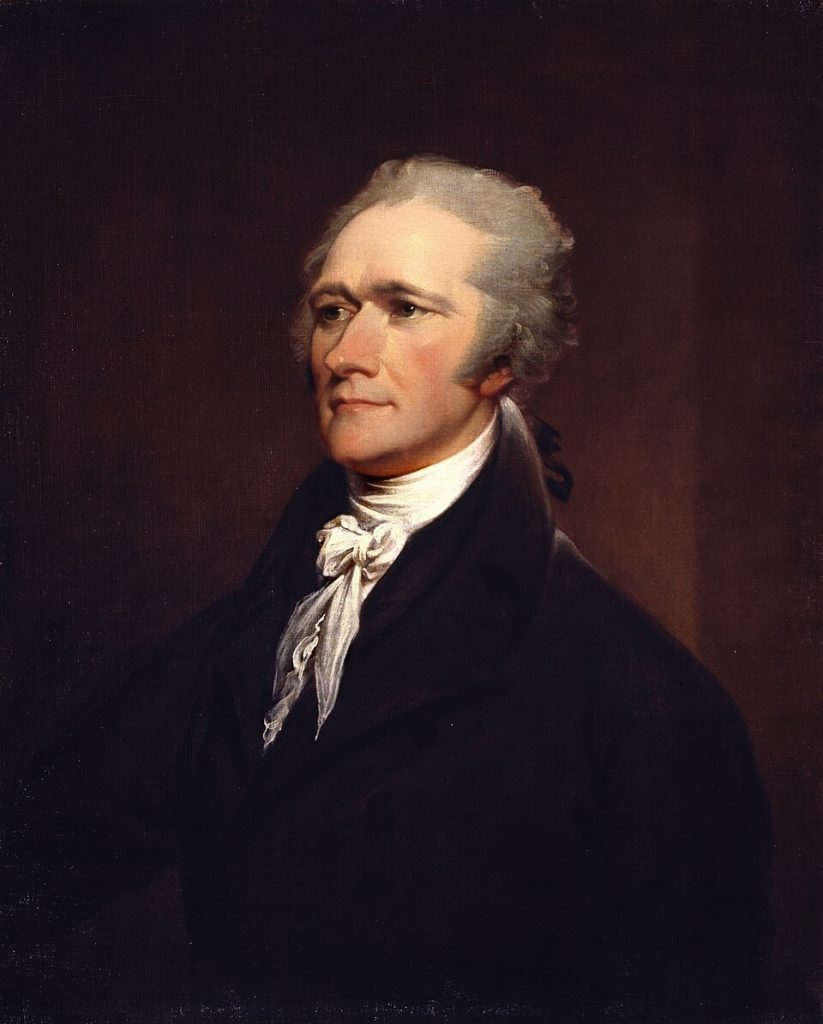

We saw last week how L. Neil Smith alters American history to fit his ideology. He dislikes the fact that the Federalist founders, who were in favor of centralized government, also tended to be the most opposed to slavery; while the Anti-Federalists he admires were fine with it. So, he rewrites the historical record to put everyone on the “right” sides.

This week is another example.

Libertarians of all stripes have a problem justifying the conquest and settlement of the New World. If they believe in property rights, as they constantly affirm, how can they give their allegiance to countries created by murder and displacement of the original inhabitants?

Some, like Ayn Rand, defended it in flatly genocidal terms. She denounced the Native Americans as savages who had no right to their own land. But Smith takes a different tack.

Here’s what happens in his fictional North American Confederacy:

Take the Westward Movement: France at war with England and the world; Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark; the Homestead Act; cattle barons and squatters; gold in California; the U.S. Cavalry, and war with the Indians. But to Ed it meant Sam Colt, whose repeating sidearm allowed individuals, rather than mobs, to make a place for themselves, self-sufficient and free. And it meant renting or buying land from Indians cannily eager to take gold, silver, or attractive stock options.

As with federalism and slavery, Smith is aware that actual history doesn’t fit easily into his assumptions. Rather than grapple with this problem, he writes a new history that’s more ideologically comfortable.

In this libertarian-friendly alternate history, the Native Americans were still displaced by white colonizers—but they were happy to move and no one felt any resentment over it. In fact, he hints they got the better half of the deal (“cannily eager”).

Needless to say, this is laughable nonsense. No group of people, in any society or timeline, is going to cheerfully vacate their ancestral homeland to make way for a wave of new settlers. I don’t care how much they got paid.

Famously, Manhattan was “purchased” for 60 Dutch guilders, or about $925 in today’s money. The Native Americans who made that deal almost certainly didn’t think they were giving the land away entirely, but granting their European guests the opportunity to share it—a welcoming gesture that came back to bite them. Obviously, the colonizers made no effort to correct that misunderstanding.

Based on interactions like this, it’s possible to imagine a coexistence scenario, where Europeans share the land with Native Americans and assimilate into their culture. But that would imply a radically different history than even this one. In Smith’s timeline, American westward expansion went more or less the same as in our world. The only difference is the political ideology that justified it.

To further show that the Native Americans did better in his reality, Smith makes one of them president:

There seems no mention of Indian trouble—a Cherokee is elected president in 1840, that same Sequoya, I think, who taught his people to read and write.

The list of Confederate presidents is short, many serving five or six terms without upsetting anybody. Year after year, their steadily diminishing power was less an object of envy or violent ambition… there was another Indian president, Osceola; Harriet Beecher was her own First Lady; in 1880, a French-Canadian of Chinese extraction was elected—so much for for the Yellow Peril, mes enfants!

Again, I can credit Smith for trying to write a less-bigoted history. Unlike Ayn Rand, who vigorously endorsed the prejudices of her era, he recognizes that racism and sexism are bad things. He wants to portray a world where they’ve diminished.

But the way he goes about it is absurd. What he’s implying is that racism is caused by government. As soon as the Constitution is abolished, all prejudice disappears in a puff of smoke, and people are suddenly happy to coexist and treat each other as equals.

What’s the causal mechanism for this? Does government somehow force people to be bigoted, even when it’s not their inclination?

The answer he’d give, I suspect, is something along these lines: Centralized government offers the choice of ruling over others or being ruled yourself. This kicks off a zero-sum scramble for power, where people turn to bigoted ideas as a way to give themselves a leg up. Without government, people no longer feel threatened by each other, so those beliefs naturally die out.

The flaw in this argument is that abolishing government wouldn’t erase people’s fears of being conquered and oppressed by others. We can see this in real history.

Slave revolts were a pervasive fear of the founding generation. To put it another way, slave owners were afraid that if enslaved people won their freedom, they’d rise up and seek vengeance, massacring their former masters. The only way to prevent that was to keep them in bondage forever. And thus, bigotry and oppression became self-perpetuating, until abolished by outside force.

Considering how tenacious racist ideas are in our world, you might think Smith could have them linger a little, if only to show how bigots find no aid or comfort in his North American Confederacy. But no. He can’t abide the suggestion that his anarcho-capitalist utopia might have any flaws, so he scripts this unbelievable scenario where prejudice simply vanishes overnight.

He goes on to explain how history after this point diverged from ours:

Mexico and Canada enthusiastically join in the “Union” half a century later. With no slavery and no tariff, there’s no Civil War.

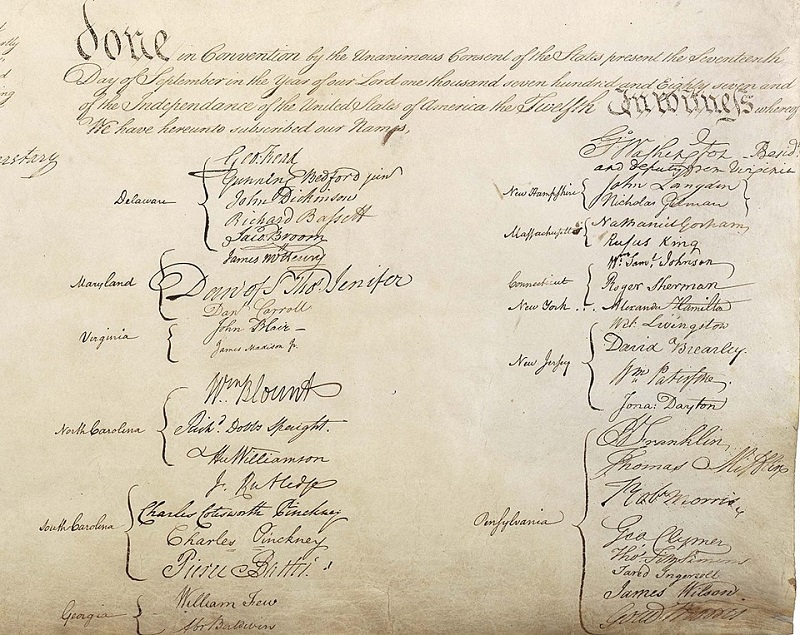

History must have some weird elastic logic, though. Hamilton got eighty-sixed, but his malady lingered on, becoming vogue with dispossessed European nobility. Splinter groups continued to clash for years, often violently, over who was really his “legitimate” intellectual heir…. In 1865, while Lysander Spooner presided over a rapidly shrinking national government, a politically shady actor, John Wilkes Booth, plodded through a backwoods tour with an English play, Our North American Cousin, when out of the audience an obscure Hamiltonian lawyer stood and shot the thespian through the head.

If you missed it, Smith groups Abraham Lincoln with those villainous Hamiltonians. (The play he mentions is the one Lincoln was watching when he was assassinated.) For all he claims to detest slavery, that speaks volumes about how he viewed the president who actually emancipated the slaves.

To close out this section, he writes that after his brand of anarcho-capitalism overtook North America, it spread throughout the world:

There’s something resembling World War I, but no trace of the Spanish-American War, World War II, Korea, Vietnam, or New Guinea. And nothing about Karl Marx, Socialism, or Communism; European revolts in the 1840s are called “Gallatinite.” Men first walked on the Moon—with women right beside them in 173 A.L.—1949! And North America fought a bitter war with Russia in 1957. The Czar was finally overthrown.

Since there was never any such thing as communism in Smith’s timeline, this makes it even more implausible that Ayn Rand still exists in this world. (According to the index at the end of the book, she was one of the past presidents of the North American Confederacy and “the first president to travel to the Moon”.) Whatever happened to only people of Native American descent being identical in both realities?

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons

Other posts in this series: