So it’s entirely possible that you’ve heard the latest ‘groundbreaking’ finding in the religious/atheist culture war, suggesting that religion is negatively associated with compassionate prosocial behaviour:

“Love thy neighbor” is preached from many a pulpit. But new research from the University of California, Berkeley, suggests that the highly religious are less motivated by compassion when helping a stranger than are atheists, agnostics and less religious people.

In three experiments, social scientists found that compassion consistently drove less religious people to be more generous. For highly religious people, however, compassion was largely unrelated to how generous they were, according to the findings which are published in the most recent online issue of the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science.

I don’t think anyone who’s been reading this blog for longer than, say, two weeks would have any trouble pinning down where I am on the believer/non-believer scale: I am doing pull-ups from the far side of the non-believer scale, encouraging others to jump off as I dangle over the edge. I am, in fact, an unapologetic anti-theist – I think that religious faith is an inherently harmful byproduct of bad brains and lack of intellectual curiosity. That being said, I am reflexively skeptical of any scientific finding that seems too good to be true. This is definitely one of them.

So, as I have before, I am taking my super skepty powers to the paper (frustratingly behind a paywall) to see if I can spot any errors.

The Claim:

Saslow and colleagues hypothesize that while both religious and non-religious people are likely to engage in prosocial behaviours (doing things for other people without the expectation of remuneration), their motivations may differ. Specifically, the authors suppose that compassion/sympathy for others is a strong motivator for non-religious folks, but not for religious ones. Put another way, atheists are good to others out of compassion, whereas theists do it for other reasons.

The Prediction:

If the hypothesis is correct, then manipulating someone’s feelings of compassion will have one of two responses. If the person is strongly religiously affiliated, they will be no more (and no less) likely to do things for other people – their compassion for others will be meaningless. If the person has no religious identity, however, they will be more likely to help out.

The Test:

In order to test their hypothesis, the authors conducted three separate evaluations. In the first study, they tested whether the level of ‘trait compassion’ (how compassionate you are generally) is associated with prosocial behaviour as a function of religious belief. They did this by running statistical tests on data from a representative survey of Americans, which has measures of compassion, religious affiliation, and a list of various prosocial activities (e.g., giving to the homeless, returning change if given too much, volunteering for charity, 7 others). The survey also had data on gender, political orientation and education, which are all potential confounders of this relationship.

A second study was conducted to investigate the possible causality of the compassion/religiosity interaction in prosocial behaviour. A crucial element of causality is establishing a temporal sequence (i.e., does cause happen before the effect?), and so two groups were asked to watch one of two videos. The ‘neutral’ video was 46 seconds of two men talking; the ‘experimental’ video was a 46-second evocative piece about child poverty with images and moving music played overtop. The groups were then asked how much money (of $10 given to them) they would be willing to donate to a stranger. Attitude toward charitable giving (i.e., how much of one’s income should one donate to charity?) was also measured.

In the third and final study, the hypothetical element of prosocial behaviour was removed by creating a real-world co-operative exercise. Participants, asked about their levels of trait compassion and their religious affiliation, were partnered up and asked to play a game in which they could divy up rewards to be spread among their partners, or keep all the points. Study points could be exchanged for money. Related exercises designed to measure one’s response to the generosity of others was also conducted.

The Findings

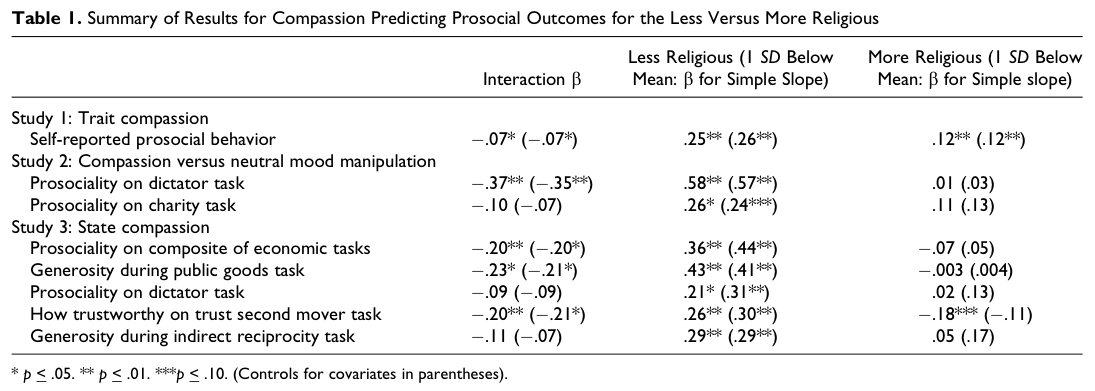

In all three studies, the main hypothesis was supported: compassion was a motivating factor in charitable giving in non-religious people; this effect was not seen (or was less pronounced) in religious people. Trait compassion in general predicted prosocial behaviour, such that those who described themselves as generally compassionate were more likely to help others regardless of their religious affiliation. In study 2 religious affiliation was associated with generosity, such that those who reported higher levels of religiosity were more likely to help others – this effect was not seen in the other two studies.

The Conclusion:

So does this study suggest that non-religious people are better than religious ones? As much as we’d love for that to be the case, this study does not lead us to that conclusion. What it says is that religious people engage in prosocial behaviours for different reasons than non-religious ones. Appeals to compassion are far more likely to work in a non-religious population, because they (we) respond to them. Whatever the reasons for prosocial behaviour in the religious (which were not examined in this study), compassion does not appear to be one of them. People in general, regardless of their religious feelings, respond to things that trigger the compassionate response – there appears to be more going on in religious populations.

The cynical interpretation of these results is that, for all their talk of ‘mercy’ and ‘loving their neighbour’, religious people do not give out of the goodness of their hearts – they do it either because they are told to or because they’re trying to get a reward*. While it’s fun to beat up on the faithful, I simply cannot arrive at that conclusion. What is far more likely is that the repeated exhortations to give to others creates a psychological attitude toward giving that has a bunch of different variables in it. Compassion is still in there, but it’s fighting with a bunch of other things – group affiliation, moralistic instruction, duty to give – that drown out (or at least moderate) the main effect of that one motivation. It would be interesting to see a study that parsed out the other reasons for prosocial behaviour in these two populations.

These studies are all pretty interesting, but they just scratch the surface of the reasons why religious folks and non-religious ones respond to altruistic cues differently. We can’t draw much stronger conclusions from this than non-religious people are more susceptible to compassionate manipulation to behave prosocially. I personally think that’s a good thing, provided our compassion is tempered with a bit of skepticism to make sure we don’t throw money at every sob story we’re presented with.

Like this article? Follow me on Twitter!

*It is, I suppose, possible that there is a certain amount of ‘just world fallacy’ going on, wherein religious people are more likely to reflexively assume that people get what they deserve, and therefore it is not their responsibility to act compassionately. I am skeptical of this idea as well, and would need to see some evidence to accept it.

It’s my experience — more or less — that when atheists do something “pro-social”, their end-result is that it makes them feel good.

When the religious do something pro-social, their end-result is that it makes them feel superior.

Of course, that’s observational/anecdotal, so counts for squat.

My parents would both qualify as ‘religious’, and they very rarely make a big show of their charity. On the other hand, there were people during the last “atheists vs. Christians” charity drive on Reddit who were smugly saying “this will show them!” I think it cuts both ways, to be honest.

I would argue that the “just world fallacy” probably affects the athiest population, too, though I won’t speculate as to the degree.

Reason: Though I know the plural of anecdote is not data, my father often says things like, “You get the [fill in the blank] that you deserve.” And when I point out situations like children, he’ll say something like, “Okay, they don’t deserve it, but their parents do!” Even if the parents were born into it as much as the kids? “They should have been trying to change it!” Even if every waking moment of every day is spent just trying (and often failing through no fault of their own) to provide their family with the bare necessities? “If they don’t like it, they could move!” Where?

And so on.

My sister does the same mental gymnastics to justify her decisions to not give to charity or not help out with something – while at the same time deriding corrupt government officials for lining their own pockets (“waitaminute, did you just say we get the government we deserve?” and cue freakout about how she didn’t vote for them so she doesn’t deserve it and me trying – and failing – to get her to understand the parallel between the local situation and that of people under dictatorial regimes. But yeah, government official embezzelling a few hundred thousand is high tragedy, but millions of people starving because their government would rather spend money on nukes than securing a reliable food supply? They totally deserve it for not fighting for freedom. */sarcasm*).

So n is only 2 there, but I’m pretty sure we’re not too superior over religious types in regard to that particular fallacy.

At least when I choose to be selfish with my cash, I have the honesty to admit it to myself: I want to eat regularly this week, so I don’t want to donate to that charity. Selfish? Yeah. I admit it.

But at the same time, I typically donate the vast majority of my disposable income each month to charity. It’s not much because I live on <$12,000 a year and all my expenses have to come out of that, but I think $80-$120/mo is better spent on cancer research, mobile prostate cancer screening clinics in rural areas to serve people who would otherwise have no access to it as it would require them to take time off work and travel a few hundred kilometers to get it, treatments for a local landed immigrant kid with brain cancer who doesn't get Medicare because she's not a citizen yet, or mosquito netting in India (a few things I've donated to in the past month) than it is on eating out, movie nights for my partner and myself and convenience foods.

I give what I can afford to give, when I can afford to give it. I won't call myself a paragon of morality or anything (I'm certainly not!) but at the same time, I think it's better than trying to convince myself I'm somehow superior to someone who had the misfortune to be born in a developing nation with inadequate education, nutrition, and resources. I'm not. I'm a person, xie's a person. I got dealt a pretty frickin good hand (white in North America, from a family that values education and scholarship, fairly good schooling in my formative years and access to supplementary educational materials when I moved somewhere with a shitty system, intelligent, relatively healthy, relatively well off even in North America – the only things against me are a learning disability I can manage, asthma and environmental allergies, and my gender. Whoopdie-freaking-do), xie got a much worse hand. If I'd been born in xie's situation, I would likely have died in infancy (10wk premature VLBW infant = dead infant if incubators, antibiotics, blood products, oxygen, surfactant replacement therapy and all the other tech that went into keeping me alive is unavailable). If xie had been born in mine, xie would likely be doing as well as me (being a grad student finishing up my degree and about to enter industry where I can expect to have a starting salary that is more than double this first-world nation's poverty line, and likely move up to triple the poverty line in five years) or better.

I know I'm probably preaching to the choir here, but I think it unnerves people to realize that so much of their lives come down to what amounts to a roll of the dice. As a tabletop gamer, I think of it as having rolled 19 on my "birth circumstance" roll. This past year, I rolled a 3 on "life events" – it's been a pretty shitty year. Not the worst possible, but probably the worst of my life so far. But really, that's all there is to it: Sometimes you're lucky, sometimes you're not. I think people should be happy when they're lucky, and deal with the bad luck as it comes. But when they're doing well, they shouldn't claim that those who have the misfortune to roll a 1 several times in a row are somehow inferior. It's just how the die rolls.

That reply became a lot longer than I thought it was going to be. Sorry to write you an essay! :\

Yeah, I had a bad reaction when you said the second study involved asking participants how much they’d willingly donate to a stranger. My answer: $0*. I feel that I am a compassionate person, but I’m not going to give handouts to anybody!

* I obviously didn’t see the video, so maybe I would react in an unexpected manner if I had.

What if you yourself are given a handout. Someone hands you a stack of cash and says “you can share as much of this or as little as you want with this person over there who didn’t get handed a wad of bills” – you’re saying your response would be “I got mine, Jack! Screw you!”?

This kind of had my bs detectors going off as well. Primarily because I also remember hearing other studies that showed poor people giving at far higher rates (relative to gross income, I believe) than wealthier people. And poor people are generally more religious. Though who knows, I don’t know anything about the other study so maybe that one was overstated just as this one was…

I’m not sure how I would have reacted:

psychologists lie to subjects all the time. One would have no reason to presume that any money given up would actually go to charity.

Then there’s economic situation – are they controlling for that? My income is currently $0. I’m struggling to pay utilities out of student loans that don’t always cover books – so I’m stuck reading in bookstores and/or libraries so I can have water and electricity.

In this circumstance, I’d likely be unwilling to give away all $10 – I’m currently a charity case and spending that $10 on certain things mean that other sources don’t have to help me and thus have more to use to help others. That’s a backdoor gift. I’m not saying it’s the most generous thing I could do, but how fair is it to those folks helping me out if I turn down resources?

Then when you add that no money is guaranteed to go to charity, psych experiments being what they are, the totality of the two would make me unlikely to give during the experiment this month.

Ask me in two months when things are better, though, and I’m likely to give all of it – or, at least, make sure all of it gets to charity, though I might funnel some of it through my partner’s kids so that they can “give” themselves. I don’t “deserve” money because some psychologist is running an experiment in my local area.

But again, would I give *during the experiment* or just earmark the money for charity later? I have no idea. It would depend on the trust I have for the experiment and the efficiency of the charity, I suppose.

I wonder how much such things affect donation: that there is a “right way” to solve problems, or at least an efficient way. Would religious people simply prefer to donate to a religious org when they got home the way that I wouldn’t trust a psych experiment to give money to the best charity?

If there is a distrust of temporal authority, it wouldn’t have anything to do with motivations for giving: they could still be generosity related, but the charities willing to be trusted with the money would be different.

Like you, it’s fairly obvious to those who know me where I fall on the believer/non-believer scale (though my “bad brains” and “lack of intellectual curiousity” are still out for the jury).

Also, I believe scientific data and studies and stats, like verses in the Bible, can be manipulated to say whatever you like.

So while I don’t know if you can draw a hard connection between charitability (or lack thereof) with religion (or lack thereof) I am extremely disappointed to say that my own personal knowledge of too many Christians is that “Love their neighbor” is a verse in a book, not a way of life.

Worse than that, for too many of them “love your neighbor” means “bully people and berate them”. For some reason it never means “offer a helping hand”. THAT, more than anything, pisses me off.

That is true only in a very superficial sense. It is possible to skew the results of a study, or introduce bias in your study design that ensures you will find the answer you’re looking for. However, science is a collaborative exercise that relies on peer review and replicability of findings. Unlike the Bible, all scientific studies are open for scrutiny, and very few people take individual papers as gospel. We actively look for things to disconfirm our presuppositions (you are commenting on an example of exactly that). If you have a specific criticism to lodge against this study, then please feel free to do so. In the absence of that, you’re just an angry old man yelling at a cloud.

My personal experience of religious people has been quite the opposite, to be honest. I have encountered very few hypocritical bigots in real life. It’s why I’m always shocked when I meet one. It’s like running into a rhinocerous. You know they exist, but you’ve never seen one in person before, and they look exceedingly silly.

It’s important to note here that religious sentiment was not associated with generosity – that is to say, religious people and non-religious people were just as likely to be pro-social. It was only when a specific motivation to be generous (i.e., appeals to compassion) were manipulated that you saw a difference in behaviour between groups. As I said, this doesn’t mean religious people aren’t compassionate, it just means that compassion is not the primary reason they engage in prosocial behaviours.

I should also point out, perhaps someone unnecessarily, that “love thy neighbour” is not a uniquely Christian idea, nor is it an originally Christian idea, nor is it the totality of Christian ethics or a representative summary of Christian attitudes toward charity.

I don’t have a specific issue with the study, and therefore I didn’t list one. I had an opinion and I voiced it. Because I don’t feel the need to expand on it or justify it doesn’t make me angry nor old.

And yes, I’m fully aware that you don’t have to be a Christian, or even religious, to “love your neighbor”.

My specific gripe, and the main point of my post, is that far too many Christians conveniently interpret “Love your neighbor” as a license to bully people. It’s doubly disgusting because Jesus himself wasn’t fond of folks like that. At. All.

So you don’t know WHY it’s wrong, but you just think it’s wrong because you don’t like science? That’s cranky old man yelling at cloud for sure.

And yes I agree, it’s quite telling that Jesus had far more to say about religious hypocrisy than he did about telling other people to get their shit together. It would be nice if more people remembered that.

It is entirely possible that a person’s propensity to feel compassion is a causal factor in making them less religious. From my perspective, I have always been compassionate and religion was at odds with that compassion. I left religion because of the conflict between its doctrines and my inner compassion.

My experience is given as another ‘possible’ way to explain the data above but is not meant to act as data supporting the hypothesis it explains.

Except the data doesn’t support your hypothesis. There was no difference in reported levels of compassion between religious and non-religious people.

Wow my words don’t translate much lately. I never said the data supported that either. Only that if compassion was a causal factor for a large number of people leaving religion you might see something like this pop up too but it would be for entirely different reasons. I wasn’t attempting in anyway to support a hypothesis with anything.

The point I was failing to make was IF religious people are less compassionate (without saying the data suggests that they are) then you might still see numbers like these but for different (and unsupported) reasons.

I guess I should stop with the talking cause my words are broken it seems.

Oh, okay. It doesn’t seem as though religious people are less compassionate than non-religious ones though. If they were, it would certainly be interesting to explore what those ramifications might be.

I had similar thoughts when I first heard about this study, and I think your analysis is excellent. For people who are have no religious motivations day-to-day, overall compassion would be the main motivation behind doing something for someone else, and compassion can be motivated by the fact that it makes the person feel good to do something nice for others (works for me!), but that doesn’t automatically mean religious people are not compassionate. A study demonstrating that would have to include an actual survey questioning motivation for compassionate acts.