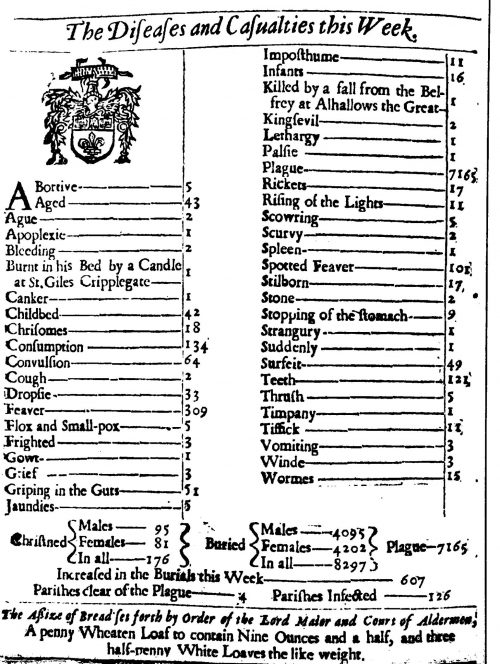

I’ve been seeing examples of those old bills of mortality going around — the lists of causes of death, week by week, in 17th century London. I thought you should know you can go straight to the source and find all the death statistics you could dream of. It’s shocking how often infectious disease is slaughtering people — plague, fever, tiffick (tuberculosis), cholera, spotted fever, smallpox, the French pox, etc. — and you wouldn’t want to be an infant, they were dropping like flies.

What’s interesting, too, is what isn’t killing them. Cancer is rare. You can find an occasional murder (or rather, “murther”), but it isn’t common. Gun deaths are noted with details (“Shot with a pistol at Saviours Southwark”) and are less frequent than executions. Everything else was killing them first. Apparently, if you really hated someone back then, it was a greater revenge to sit back and wait for them to die a miserable death from worms or a bloody flux.

There are definitely some advantages to living in the 21st century.

London Pride is tomorrow. I think I’d prefer to take my chances with the seventeenth century.

121 people died of… Teeth?

Also, I thought Consumption was TB, not Tiffick (whatever that was). Maybe two different symptom sets for what we now know to be the same disease?

I have to say, though, I do love this one: Griping of the Guts. Not that I’d like to die that way myself, mind you…

DonDueed @ 2:

I would imagine that infections from abscessed teeth could be quiet deadly in this pre-dentistry era.

Yeah, a lot of old-timey names for diseases in a period before people knew about germs and where medical science was still largely based on the ramblings of Ancient Greeks. 7165 from “Plague?” OK, which one?

As I understand it, dying from “grief” was merely the polite way of to say one died from suicide.

EDIT: …a polite way of saying that one…

The English comedian David Baddiel had comedy bit about these bills of mortality back in 2002 for the Peter Cook Tribute comedy show. You can see it here.

@2, @4: It mostly referred to death during teething. Apparently infants were prone to infection during that time, and malnutrition may have contributed as well.

eamick @ 8

Thanks! Ya learn sumthin’ every day.

PZ:

No, cancer was not at all rare. A great many people died of cancer. I recommend reading The Emperor of All Maladies for a comprehensive history of cancer. Even when it was properly diagnosed, it wasn’t called cancer, and the disease[s] was not well understood. About the time you’re posting about, one physician noted that a great many chimney sweeps, all of a young age, had a degenerative disease of the testicles. Turns out it was cancer, and of course, they all died of it. The oldest known and recorded case of cancer was around 3,000 years ago.

Rising of the Lights. So very poetic!

Would NOT want my death recorded as “winde.” I can only imagine one’s final thoughts being of extreme frustration… or inconceivable satisfaction.

Milde Distracten Auk has never been recorded as the cause of death. Sinking Atlantis (not every time, she claims), eating Fromagers (by accident, she claims — they didn’t let go of the cheese fast enough), don’t count.

Compared to nowadays, it was rare. Today, cancer is the second leading cause of death; browse through the 17th century archives, and you’ll go for weeks and weeks, seeing only sporadic mentions of cancer deaths. Also, the chimney sweep cancers were primarily from the 19th/early 20th century.

“Teeth” is shorthand for kids who died at the age they were teething. “Chrisome” refers to kids who died in the first month after birth. There’s a lot of subcategorization of infant deaths because they were so frequent.

By the way, “imposthume” is death by abscesses. Strangury is death by failure to urinate, as by bladder stones. Sure are a lot of unpleasant ways to die.

Looked up King’s evil, it is another name for scrofula, which is tuberculosis of the lymphatic system, so named because it was supposed to be cured by the touch of the reigning sovereign.

I caught the suddenly once. Several hours waiting in line at the urgent care clinic solved it.

The sheer prevalence of infant death in pre-industrial societies hit me most forcefully when I was involved with cataloguing Roman grave inscriptions. About half of them are for children under the age of two, and about half of the rest are for children under the age of 16.

Roman practice was generally to record in precise detail how long the dead person had lived. Often down to the day. For babies it was not unknown to record it down to the hour.

Also common was to record the cause or occasion of death. Tellingly, most of the adult ones tend to be accidents (fires, building collapses, crushed by crowds) or attacks rather than disease – although that is doubtless heavily skewed by the fact we have lots of grave inscriptions from military camps and the city of Rome itself – which was lawless and violent to a great degree.

Grave inscriptions in Iqaluit have a very large number in the late teens. They don’t mention the cause of death, but at that age it’s mostly suicide.

Oh man, I can truly relate to “Strangury”. I had a “urine retention episode” a couple years ago. After half a day of growing discomfort that included several hours of waiting around in the ER to get treated, I was in some pretty serious distress.

My problem (which was caused by a drug interaction) was corrected by catheterization. At one point I asked the attending nurse (somewhat rhetorically) what became of people who had the same problem a couple centuries earlier. The answer: “They died.” …of Strangury, apparently.

Incidentally, I recently learned that Benjamin Franklin invented an improved catheter. It was made of “flexible steel”. Ouch.

♫ Shrivel up with age

Blow your top in a rage

Fail to pee until your death

Be born dead, never drawing a breath

Vile ways to die

So many vile ways to die

Vile ways to die-hi-hie…

So many vile ways to die. ♫

Aged, Apoplexic, Bleeding, Lethargic, Consumption, Convulsion, Joe DiMaggio… we didn’t start the fi-yah…

Reportedly cities had negative natural population growth before the advent of modern sanitation.

They only grew because of immigration, i.e. economic opportunities and a modicum of freedom compared to being a peasant.

abbeycadabra

I recognize that tune!

For everyone else: https://youtu.be/IJNR2EpS0jw

@Dondueed Re: tiffic

Yes, it looks like tiffic (or tissic, or phthisis, all alternate spellings of the same root word) and consumption both referred to the same root disease, a fact not appreciated at the time. TB can present in many ways, including not at all (some carriers are asymptomatic). It’s hard to tell from this far away in time, but it seems like tiffic etc. was applied when the primary symptom was a dry cough, and consumption when the main thing noticed was the emaciation of the body.

PZ most cancer would have gone undiagnosed and “cause of death” ascribed to one of the symptoms. In the absence of an autopsy (which weren’t ever done at this time I think) no diagnosis of, say, lung or brain cancer would be possible. Certainly blood cancers or those of, say, pancreas or liver, were totally unknown. Also there was no medical theory which could account for cancers. Only when a cancerous growth was obvious from the outside would such a diagnosis be possible.

@23 WMDKitty

tee hee hee

I love that one guy died “suddenly.”

And along with the 172 infants and small children’s deaths, there are also 42 childbed deaths. And 176 live births. (Plus 17 stillbirths.) Being a woman in child-bearing age was a frightening thing; by these numbers, almost one out of 4 women died in childbirth, and then most of the time, the babies died anyhow.

I found this Mental Floss article helpful in explaining what various of the entries mean.

Will add my own 2 cents in here on the cancer issue – we are talking about a time period in which many of the people listed didn’t live long enough to **develop** it in the first place. A lot of cancers only start showing up past a person’s 50s, and take decades to kill them, and the average live expectancy in the 17th century was 39.7 years. By contrast, this is what you get just from the first return, on the first page, of Google, when you put in “average age of cancer diagnosis”: “Adults aged 50-74 account for more than half (53%) of all new cancer cases, and elderly people aged 75+ account for more than a third (36%), with slightly more cases in males than females in both age groups.” And, ironically, the first thing returned is from the UK’s cancerresearchuk.org

So, to claim that cancer wasn’t killing people back then might be absolutely true. Was it rare, well, again, true. But so where drunk drivers before Henry Ford made it possible for almost anyone to own a car. This is such a fundamentally basic mistake PZ it surprises me.

#30 Kagehi

The average life expectancy in the 17th century was under 40 years. Sure, but that included a huge early death rate for children and infants, which brings the average down. Once someone had made it past those dangerous first years, their life expectancy was much higher than 40, even given high risk occupations such as the military and motherhood.

It’s a long time since I’ve looked at the figures, but I remember that even in my grandmothers’ time, the early 20th century, even here in Canada, about 50% of newborns made it to their 5th year.

Cancer is not a new disease.

It’s incredibly difficult to estimate cancer rates in pre-modern societies. What we can say is that cancer was uncommon as a cause of death, but probably not rare (medical definitions vary, but rare usually means less than 1 per 1000 people) and that most cancers would not be recognised in the 17th century. Although there is only one case positively recorded as “canker”, it’s likely that at least some of the other causes listed were cancers, for instance fatigue, stopping of the stomach, griping of the guts, ague, strangury, vomiting, winde, convulsions, and possibly even some of the consumption cases could all have included some cases of unrecognised cancer.

But having said that, the rate of death by cancer is certainly much higher than it was even 100 years ago. There has been some environmental impact (tobacco still accounts for around a fifth of all cancer deaths, obviously this would be rarer in C17 London and outright impossible in pre-Columbian Europe), but mostly it’s simply the we live longer and cancer becomes much more likely the older you get as it takes time to accumulate the necessary mutations.

@31 Susannah

Good point, but.. honestly, we are also talking about a time period which it would have been quite common for toxic chemicals to be used is medicine, as well as bad drinking water, diseases, etc. which could have, assuming one lived long enough, contributed to cancer. Its very unlikely that it was as rare as it would seem, but also impossible to say, with certainty, how common it would have been, giving equal likelihood of someone living long enough to get it (and this includes children that just where not around long enough to become adults at all).

Basically, its still a glaring mistake to call it “rare”, instead of, at best, “unknown”. To call it rare requires making the assumption that contributing factors to it “only* exist today, and nothing similar existed then (and, like I said, just basic knowledge of medicine, and the misuse of deadly things for it, did happen, and is one of the major causes today, as it would have been then, and, if anything, it could have been, among those who could afford the latest fad medication, worse than it is today. An irony, since its likely that those people where also the ones most likely to live long enough, since they had adequate food, and resources, to suffer from it.)

So, yeah, I don’t believe, for a moment, the assertion of “rare”, and I have serious reservations as to it being “less” either.

Kagehi@33–

Despite limitations, we can be extremely confident that the prevalence of cancer is much higher now than it was in pre-industrial Europe. So while I agree with you that actual cancer was probably not rare in C17 London (although frequently not diagnosed), I have no reservations at all that it was much less common than today.