Call me naive, but I believe Joe Biden could have won the 2024 election.

Nothing is guaranteed, of course, and no one can foretell the future. Every politician has a unique set of strengths and weaknesses. And in a nation as split down the middle as America, it’s almost impossible for any candidate to take an insurmountable lead. However, I’m convinced that the Democratic nominee has a solid chance of beating Trump again, whoever it is.

I didn’t buy into the intense dooming among liberals after the first debate. I remember a similar collective freakout in 2012, after Barack Obama underperformed in his first debate against Mitt Romney. Look how that turned out.

I don’t believe elections are decided by debates. As a rationalist, I wish voters chose who to support based on which candidate made the best argument. But they don’t. The vast majority of voters cast their ballots because of established partisan loyalty, specific issues they care about that are aligned with one party, and/or personal satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the state of their lives that they project onto political leadership.

In 2024, these structural factors favor Team Blue.

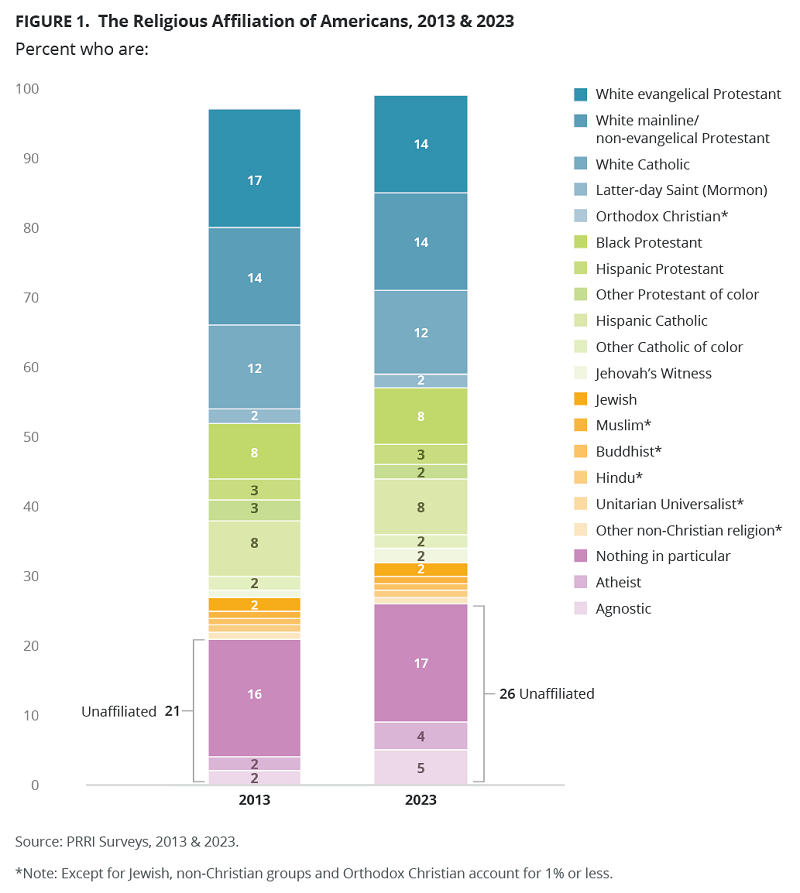

Start with basic math: there are more Democrats than Republicans. The Democrat won the popular vote in five of the last six elections. Slow but steady demographic turnover only bolsters this advantage, as old white conservative Christians die off and the electorate becomes more diverse and more secular.

It’s only the anti-democratic Electoral College that gives Republicans any chance. Even so, Trump’s win in 2016 – squeaking by in a few crucial swing states, while losing the popular vote by millions – was the equivalent of getting a royal flush on the first hand in poker. It was pure luck, not the result of a well-thought-out strategy. Since then, he’s done nothing to bolster his appeal or expand his base (as his VP pick, J.D. Vance, demonstrates).

A recession can spell doom for an incumbent, but President Biden’s economy has defied the pessimists. His policies have strengthened unions, reduced the burden of student loan debt, and stimulated investment and infrastructure spending on a grand scale. GDP is growing at a robust pace, job creation has skyrocketed, wages are rising, and inflation is cooling off.

At the same time, Democratic voters are fired up over abortion bans. The Dobbs decision sparked a massive backlash that’s propelled Democrats to numerous election victories over the last two years, including in purple and red areas. The midterms, which almost always go badly for the incumbent’s party, instead resembled a blue wall in 2022. In my congressional district, abortion carried Tom Suozzi to victory, despite an all-in effort by Republicans to inflame a racist, anti-immigrant panic.

There’s no reason to believe things will be different this time around. If anything, this effect will be stronger. One of the most potent motivators in an election is negative partisanship: hatred and fear of the other side. That’s something Republicans have been exploiting successfully for decades, portraying every Democratic candidate as a threat to good, white, Christian Americans. Now, for once, they’re on the wrong side of this. Democrats hate Trump with a fiery passion; they’d vote for literally anyone other than him.

All these structural factors combine to give the Democratic nominee an advantage. The identity of the person is less important.

That’s why, at first, I was neutral between Biden and Harris. Biden’s age is a liability; I can’t deny that. On the other hand, as much as I hate to think this way, there are sure to be voters on the margins who would have supported a white guy, but won’t vote for a woman or a person of color. And we can be sure Republicans will resort to the most vile racist and sexist attacks they can imagine. I may be too cynical – after all, Barack Obama won twice – but for those of us who lived through 2016, the scars are deep and lingering.

However, after digesting the response and mulling it over for a few days, I’m coming to like Kamala Harris more. There are two major reasons that changed my mind.

The first is an immense surge of grassroots enthusiasm. The party immediately coalesced behind Harris, and in the wake of her announcement, she raised record-shattering amounts of money from small donors. Young voter registration also spiked to record numbers. Those signs of unity, passion and enthusiasm bode well for an election where turnout is sure to matter.

The second is that Republicans are outraged about it. They’ve spent months drumming up fake controversies to lay the ground for a campaign against Biden. They were caught flat-footed by his passing the baton. Trump, hilariously, whined that Democrats should reimburse him for the money he spent on anti-Biden attack ads.

Whatever I might think, they clearly believed they’d have had a better chance against Biden. In politics and in war, doing the opposite of what your opponent wants you to do is sound strategy.

Harris has some unique strengths of her own, as well. Not only does her candidacy neutralize the age issue, it flips it around and makes it a liability for Trump, who’s now the oldest candidate in the race by far. As a former prosecutor, she’s well-positioned to attack him as the convicted criminal he is. And as a woman, she has the power to make reproductive choice an even more potent issue than it already is.

Obviously, this is no reason for complacency. If anything, it’s an all-hands-on-deck moment. If you can knock on doors, or make calls, or write postcards, or donate money, or just talk to your uncommitted friends and family about the importance of voting, you should. America is on a precipice between democracy and fascism, and our choices will shape the future for our lifetimes. The stakes couldn’t be higher. But we can win, and save the future, if we work together and don’t lose hope.