The Probability Broach, chapter 2

The second chapter of TPB begins with a vignette:

ATLANTA (FNS) – Over 100 heavily armed agents of the Patents Registration Tactical Arm staged an early-morning raid on a small suburban home here, ending the fugitive careers of two Coca-Cola executives, in hiding since January. Federal News Service has learned that the two, listed in warrants as “John Doe” and “James Roe” were taken to Washington’s Bethesda Naval Hospital for what PRTA officials term “therapy.” Unofficially, spokespersons expressed hope that the two would divulge certain “secret formulas” held for over 100 years by the Atlanta-based multinational corporation. Proprietary secrets of this nature have been illegal since passage last year of the “Emergency Disclosure Act.”

—The Denver News-Post

July 7, 1987

L. Neil Smith is mocking what he sees as government’s power-mad tendencies. In his view, the state deprives people of what rightfully belongs to them. This includes sending jackbooted thugs to persecute corporations and deprive them of their valuable intellectual property.

But there’s a problem: in his preferred politics, the same thing would happen. In an anarcho-libertarian society, it’s impossible for patents to exist!

Smith believes that there should be no government and no laws – full stop. That means no protection for intellectual property. If you invent a great new product, anyone else can reverse-engineer it and start selling it themselves.

We’ll return to this point in a moment, but first, let’s pick up the storyline. Among the late Dr. Vaughn Meiss’ possessions, Win finds a business card for the “Colorado Propertarian Party”. It’s the only lead he has, so he goes to check them out.

The Propertarians rent a suite in a grubby office building on the bad side of town. Win knocks and lets himself into their office:

The place was freshly painted and didn’t smell of piss like the rest of the building. It was brightly decorated with posters: “ILLEGITIMATE AUTHORITY” IS A REDUNDANCY and TAXATION IS THEFT! A small desk with a telephone and answering machine occupied one corner beside a rack of pamphlets. I could hear the illegal rumble of an air conditioner. First time I’d been comfortable all day.

A woman entered, tall and slender, thirtyish, lots of curly auburn hair and freckles. She wore the jacket to a woman’s business suit and faded blue jeans, a lapel button declaring I Am Not a National Resource! “I’m Jennifer Noble. Vaughn is dead?”

Win asks some questions about Vaughn and his beliefs, trying to get a handle on who might have wanted him dead. Jennifer Noble, who carries the exposition ball in this scene, explains their politics to Win: “Propertarians believe that all human rights are property rights, beginning with absolute ownership of your own life.”

This sounds reasonable, but on closer look, it falls apart. Smith holds property rights as sacred, but believes there should be no government. Those positions are self-contradictory.

Property rights (and rights in general) don’t just exist of their own accord. They’re not natural phenomena, the way mountains and storm systems are. They’re human creations; they arise as the result of a democratic covenant, and they can only survive if there’s a government that upholds the rule of law. Without a means of enforcement, people are helpless to stop others from stealing the things they create.

A case in point is the story of Ephraim Bull, a 19th-century American horticulturist who tried to breed a grape that could grow in New England’s cold climate. He spent years planting, crossbreeding and selecting vines, until he came up with a sweet, fragrant, cold-hardy cultivar: the Concord grape.

The Concord grape was a runaway success. To this day, it’s the most commercially successful variety, widely used to make products like jelly, juice and wine. But Bull made almost no profit from it, because nobody bought the grapes from his vineyard. They just planted the seeds and grew their own. Bull’s bitter epitaph reads: “He Sowed, Others Reaped”.

In an anarchist society such as Smith envisions, with no patent laws or courts, this kind of thing would happen all the time. Companies could skip burdensome, expensive R&D and just copy their competitors’ products. Of course, this is a Prisoner’s Dilemma that ends up in a race to the bottom. Any one business can reason thusly: Why should we pay the cost of innovation when everyone else will free-ride on our efforts? And if everyone reasons this way, innovation grinds to a halt.

An even bigger problem is plagiarism. If I’m an author and I publish a book, someone else can print their own copy and sell it. In fact, they can sell it for cheaper than I can, because they didn’t have to pay the upfront costs of writing it!

This would be a massive disincentive to authors, especially for research-heavy nonfiction and academic works like textbooks. It would make it virtually impossible to write for a living. (Even as it is, plagiarism is a gigantic problem on Amazon; imagine how much worse it would be if there was no copyright at all.)

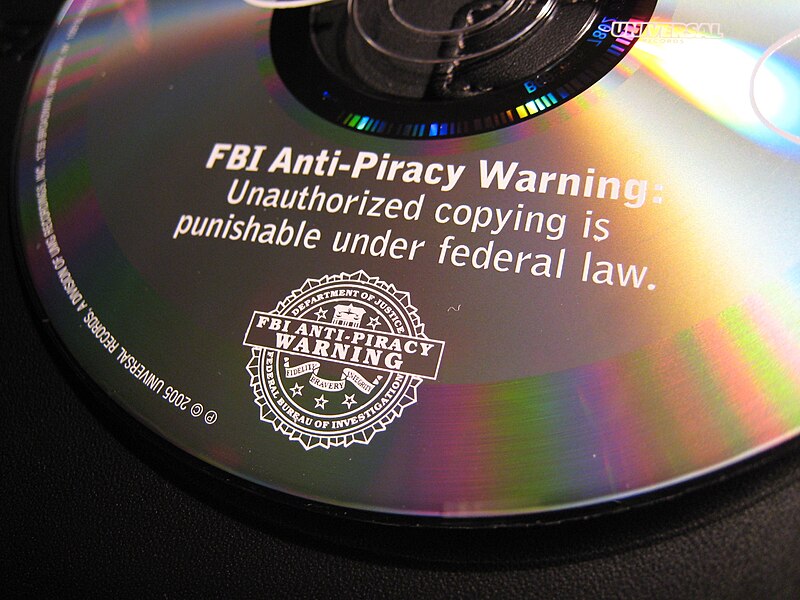

The same problem applies to all art. In an anarchy, there’s no law against piracy. If you spend hundreds of millions of dollars to make a movie, with top-notch actors and expensive special effects, can I just videotape it and hold screenings in my living room, paying you none of the royalties? If you’re a musician and put your blood, sweat and tears into a new album, can I buy one copy, churn out my own recordings and undercut you by selling them?

In an anarchist society, people only have what rights they can protect by themselves. If you squint and fuzz your vision, you can imagine how you might be able to defend your person, or your house, against someone with evil intentions. But it’s obvious how impossible this would be for abstract rights. If I invent a new gizmo or write a book, would I have to become a globetrotting vigilante, tracking down anyone anywhere who infringes it and using my own gun to enforce my copyright against them?

This is a wedge issue for libertarians. Ayn Rand believed in patents (an evil government forcing her heroes to surrender their patents is an important plot point in Atlas Shrugged), although she ran into philosophical difficulties justifying their legitimacy while also claiming to oppose initiation of force. Still, at least she understood how patent rights could incentivize research and creativity.

L. Neil Smith never comes to terms with this problem. His anarcho-libertarian utopia has ultra-advanced technology, but it just exists magically, as if it materialized out of thin air. We meet a few of the people who invent it, but there’s no explanation of where their funding comes from, or how anyone could have this as a job if there’s no reasonable expectation of turning a profit from it.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons, released under CC BY 2.0 license

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series:

Well, books were written and things invented before intellectual property. However, to achieve success people had to keep things secret (guilds did this) or depended on patrons, from what I understand. As you say, this would likely lead to less innovation, as was the case in the past. The most plausible anarchist formulas I’ve seen are just government by another name: “anarchy” is a term of art for many. In anarcho-capitalism, it’s been presented sometimes as basically a gated community state. The only difference is the citizens would explicitly consent to abide by its laws through a contract. I am curious to find out what Smith proposes, but to judge from what you’ve related so far, like a lot of utopians he will gloss over most details.

It’s true that books were written and things were invented before we had patent and copyright laws. However, I’d say that in those eras, very few people could afford to make that their profession except for the wealthy, who didn’t need to depend on it for income. I think it’s plausible that the rate of innovation increases when more people can take up research with the expectation of making a living from it.

In a true post-scarcity society, people might go back to creating just for the joy of it. But Smith’s utopia is still depicted as one where you need to earn money to live, so that option isn’t open to him.

I agree with that, just noting it. Of course, with the printing press it also became much easier to even make books. I don’t think it’s coincidental that the printing press preceded copyright either, since more books made the protection demanding.

Many of the anarcho-capitalist libertarians I talked to back in the day just made a carve out for property rights. The government could do nothing EXCEPT enforce property rights. Some recognized the contradiction. Others were oblivious to it.

Minor nit: cultivated grapes are not grown from seed, but from cuttings; vegetative propagation. As I recall this is because grapes, like many other fruit plants, have very variant genomes, so there’s no guarantee that an offspring seed will have all of the desirable characters of the parent that produced the fruit. Farmers didn’t know about genes back then, but knowing that seeds didn’t produce fruit exactly like their parent goes back thousands of years.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vegetative_reproduction

All the documents I can find on the web says that Bull, and other plant nurseries, sold cuttings.

One detailed paper says Bull sold vines at $5 per each, which, says at least one inflation calculator, is roughly $200 today. He made $3,200 the first year, or roughly $121,000 today.

It was just that after that first year, his sales dried up, because the other plant nurseries were selling cuttings as well, and not giving royalties.

Thanks for the correction! Just from a cursory search, it looks like there are some varieties of grape that can be grown from seed, but most of the ones you’d buy in the store are clonally propagated.

It’s damn hard to research stuff like this now that there’s so much AI slop on the internet.

I’d say that getting $121,000 for a one-time job isn’t too shabby.

The only way out of the anarchists’ dilemma I can see here is to find a way to decouple “work” from “making money”, at least partially. There’s a lot of valuable work that isn’t, and often can’t easily be, directly remunerated, particularly without intrusive enforcement systems that create their own serious problems in turn (such as monopoly formation). And right now there’s people who get heavily remunerated for doing sweet fuck all, such as the entire rentier class. Redistributing all passive income evenly over the whole populace might be a good start, and all it would take is some changes to the income tax laws …

The Coke formula is hardly a secret. It was published in 1983 by William Poundstone with no adverse effect on the company. Smith’s being very silly here.

And I suppose it might be possible to guard physical property without a government – to a limited extent, but intellectual property rights are purely a creation of the government (software companies tried to “copy protect” their software themselves – but those attempts all failed until it became illegal to tell anyone how to break copy protection)

There’s an entire parallel economy going on in software, where the entire point is that no-one is stopping you from copying it; in fact, it’s encouraged. The GNU General Public Licence is what’s called a “strong” licence in that the permissions it affords you over and above your statutory right of fair dealing are conditional, and apply only if you share any changes you may have made with the rest of the world on the same terms as the software was shared with you in the first place. If you tried to make a modified version of, e.g. the Linux kernel proprietary, you would be exceeding the permissions, in breach of copyright and subject to the full force of the law just as if you had tried to sell a modified version of Microsoft Windows as your own work.

All of the absolutist political positions run into some variation of this problem. All of the successful government are a mix of theoretical government types blended to make something that works. Total anarchism doesn’t work, total independence doesn’t work, total central control doesn’t work.

The US government is a mix of centralized, distributed and local. Some, like police are divided across every level. Others such as military are concentrated at the top. A few bits, such as fire services are largely local.

What trips up a lot of people is not understanding that the right distribution of these services changes over time. Better communications, transport and information pushes things up the chain. More policing has to be done at the Federal level because gang leaders can run gangs from great distance, even other countries now. Environmental control has to be done at a very high level for the same reason. It make no sense for a single town to drive out a polluting industry when they can just move up the river a bit and go back to dumping toxins.

Finance has reached the point it’s global 24 hours a day. The Federal reserve has to monitor markets around the planet continuously to make sure that markets in other countries are not screwing the dollar value at 2am.

[Smith’s] anarcho-libertarian utopia has ultra-advanced technology, but it just exists magically, as if it materialized out of thin air.

So even in this libertarian fantasy, “the Magic of the Marketplace” and “the Invisible Hand” only exist in the other/alternate universe? That kinda says something.

…Smith’s being very silly here.

As we saw in the first post introducing this book and its author, Smith really seems to be just plain bonkers: pathologically anti-government and pro-gun to the point of being completely divorced from reality and common sense.

The Coke formula is hardly a secret. It was published in 1983 by William Poundstone with no adverse effect on the company.

You’d think someone would have at least tried to copy it to improve Pepsi!

Bekenstein Bound

Breeding something like a new grape variety isn’t a ‘one-time job’ it’s years of work. Even if Bull had been lucky enough to breed concord from his first set of crosses it would have taken several years to grow enough vines, to a mature enough state, to enable him to sell 640 cuttings in one year. So it was more likely $121 000 for a decades work, $12 100 a year doesn’t sound much to me.

It was a decade’s worth of work that he enjoyed, though (presumably; or else he would have given up and done something else); so it’s £121 000 plus ten years’ fun.