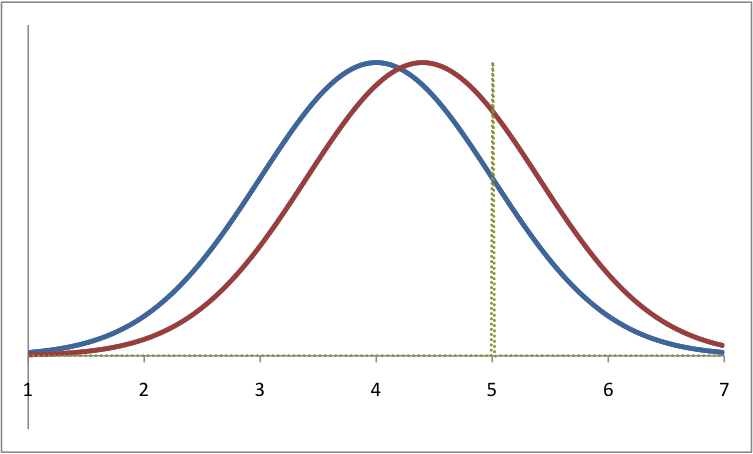

Previously, I tried to illustrate my take on the “accommodation vs. confrontation” issue using a model from statistics. In brief, I pointed out that by asserting a strong, persuasive position it is possible to shift a population of people along a continuum from absolute belief toward absolute disbelief. This shift can occur despite the fact that you may not move a single strong believer into a position of disbelief:

In the graph above, the blue line represents the distribution of a priori level of belief in a proposition (to wit, the existence of a god/gods with 1 reprsenting gnostic theism and 7 representing gnostic atheism), and the green dotted line is what I call a “precipice of belief” – the point at which people begin to ask serious questions and doubt the validity of their beliefs. The red line is a hypothetical distribution after someone has made a compelling argument against belief. Notice that many people have crossed the “precipice”, particularly those that were already close to questioning. Note also that none of the “strong” believers (those 1s, 2s and 3s) are atheists now, but are still somewhat shifted.

The question inevitably arises in such discussions: is it necessary to be aggressive? Doesn’t being aggressive and employing mockery of people’s beliefs make them less likely to listen to your argument? Wouldn’t it be better to state your case in a nice non-confrontational way, rather than arguing from an extreme point of view? I outlined my objections to this argument in the first post:

In general, there are 4 major objections: 1) someone who believes in something because the opponents are mean isn’t rational; 2) there would have to be a lot of people turned off for this to be ‘counterproductive’; 3) minds change over a period of time, not at a single instant; and 4) believers are not the only people in the audience.

I feel it’s important to expand on those points.

1. Someone who believes in something because the opponents are mean isn’t rational

If we grant for a moment the existence of people who will simply move further to the left, or completely shut down, if someone isn’t nice to them (and I’m sure they’re out there), this still fails to be a reasonable objection to the use of aggressive rhetoric. If the strength of your belief is predicated on the disposition of your critics, then you’ve abandoned rationality and are doing things from an entirely emotional perspective. As an analogy, imagine someone who believes in science primarily out of a hatred for hippies and anti-vaxxers. Her belief in science has nothing to do with its actual efficacy, but rather an ad hominem rejection of the opponents. Her reasons for belief are therefore non-rational, and a reasoned argument against them would be a complete waste of time.

It is certainly someone’s right to believe or disbelieve for any number of reasons, but then we have to stop pretending that a rational argument, no matter how friendly, will sway them in the slightest. It therefore requires a different type of argument to convince someone with this mindset, one that is based on emotive reasoning rather than logical. Unless “Diplomats” are advocating abandoning reason as a means of dialogue, then we have to accept that a variety of approaches are necessary.

People whose beliefs will not respond to logical reasoning represent only one portion of the population of believers, and those ones are likely in the 1s and 2s, rather than close to the precipice of belief. After all, if you’ve drawn the cloak of your belief around the shoulders of your brain that tightly, you’re probably not interested in hearing dissenting opinions anyway. It’s also nearly impossible to find arguments that aren’t offensive to believers, when any questioning of their faith is seen as an unforgivably rude insult.

2. The issue of ‘counterproductive’

One of my least favourite words that always pops up in this argument is “counterproductive”. The assertion is that being aggressive turns more people off than it turns on. If we look at that curve in the above image, we can see that while no ‘strong believers’ have crossed the “precipice”, quite a number of those living in the middle are now in a position to seriously question their position. In order for this to be a “counter-productive” shift, an equal or larger number of people would have to be pushed away from questioning their belief.

There is no evidence to suggest that such a shift happens. What is more likely is that people simply ignore a given argument if they don’t like the speaker, and their level of belief remains fixed where it was before. Viewed in isolation from an individual level, this may look like a failure of the argument, but we have to remember that we’re dealing with a distribution of beliefs in a population, not the efficacy for any one person. Furthermore, the audience for an appeal that includes aggression is, by definition, those who are mature enough not to dig in their heels every time their feelings get hurt.

3. Changing minds takes time

The “Diplomat” position also makes the implicit assumption that the goal of a given argument is to turn someone from a believer into a non-believer immediately. This is an attractive fiction, but a fiction nonetheless. People do not arrive at their beliefs all at once, but rather over a period of time. It is a rare person who can look at even the most compelling argument against a position and switch their beliefs immediately. More common is that a series of kernels of cognitive dissonance are introduced, whereafter more questions are asked. This process eventually leads to the changing of minds.

As evidence, consider the stories of people who are outspoken atheists. Many of them start from a position of strong belief and then turn to a more liberal form of their religion. Then, as time progresses and they allow themselves to ask more questions, they slowly (over a number of years, in my case) progress toward a complete rejection of those religious beliefs, then of religious beliefs altogether. More rare are stories of people who have a friend point out, in the nicest language possible, that YahwAlladdha is fictional, after which they say “those are good points – I’m an atheist now!”

4. Believers are not the only audience

Once again, I am up against the word limit for this post, and I think I can devote an entire 1,000 to the fourth (and in my mind, most important) of these defenses of aggression. What I will do instead is summarize what I’ve said above and leave off the final part of this discussion for next Monday’s “think piece”.

Much of my objection to the “Diplomat” position is that it demands exclusivity. It says that being confrontational is inherently a bad idea because it fails to convert a believer into a non-believer. My contention is that it is neither desirable nor practical to focus on converting individual believers into atheists, especially given the diversity of belief within the general population, and the fact that changing minds takes time. We must remember that we are speaking to a variety of people, who are at different stages in their journey away from belief. One approach is not going to reach everyone, and pushing hard can move people who are already close.

Like this article? Follow me on Twitter!

I really appreciate the attempt here to drill into communication strategy – I think this is exactly what this movement needs: an open, honest discussion of strategy.

That said, there are serious problems with the first three of your points:

1) It is not at all irrational to be more skeptical of, and resistant to, arguments which come from a source you believe does not have your best interests at heart. If someone introduces themselves to you as someone who detests you and thinks you’re a fool (I don’t mean literally – I mean through what they say and how they say it) it is highly rational to be on greater guard for manipulation from that actor. In Aristotle’s terms, denigrating your audience drains your own Ethos, and the audience has a legitimate, rational interest in the Ethos of the speaker since it bears on the likelihood they might be trying to manipulate them or persuade them to an undesirable outcome. Skepticism of aggression is therefore rationally warranted.

Further, this premise rests on a very outdated view of cognition in which emotional and logical reasoning are neatly partitioned. No empirical data supports this outdated view. It is, in short, completely wrong. The best single book on this topic is Westen’s ‘The Political Brain’. ‘The Sentimental Citizen’, by George Marcus is also good on this front. From the philosophical side you’ll want David Best’s “The Rationality Feeling” and Kate Elgin’s “Considered Judgment”. I can recommend more if you like, or even send PDFs of some papers.

2) You have presented no empirical evidence to support your view that aggressive attacks shift people in the desired direction. That is essential to present before you even ask the question of whether the strategy might be “counterproductive” – what’s the evidence to believe it is productive in the first place?

3) I don’t disagree with your point, I just disagree that diplomats take the view you ascribe to them.

4) I agree with but again don’t think many diplomats would agree.

So there’s not much here to support aggression as a tactic.