The Probability Broach, chapter 13

Win Bear’s appearance in the North American Confederacy has proven that the Probability Broach works. It can establish contact with parallel universes and transport people and things between them. The scientist who built it, Dr. Dora “Deejay” Thorens, rushes off to tell her lab partner—who, it turns out, isn’t human:

Ooloorie Eckickeck P’wheet first conceived the Probability Broach in 192 A.L., when Deejay Thorens was a mere calf whose present position was occupied by another landling. Unfortunately, she’d been looking for a way to get to Alpha Centauri, and was particularly disappointed since her mathematics had seemed flawless.

We already met talking chimpanzees and gorillas in the NAC, and now Smith adds talking dolphins and porpoises. As with the primates, there’s no mention of humanity genetically modifying them to uplift them to intelligence. In fact, the text says they were intelligent all along, and we just never noticed until we had a society advanced enough for them to want to join it.

This raises some uncomfortable questions about what human-cetacean relations were like before this revelation. How do they feel about being hunted for meat by humans, or trapped and drowned in fishing nets, or fatally beaching themselves while fleeing from our sonar? What about dolphins being abducted from the wild and forced to perform tricks in aquariums—do they consider that slavery?

Do they have any hard feelings about all this? Did humans have to pay reparations? Smith never addresses the issue, although it does remind me of one of the best stories The Onion ever published.

“I’m gratified to meet you, Mr. Bear. You and your counterpart from this continuum are a welcome though scarcely necessary confirmation of my hypotheses.” This Telecom was different, a wheelchair with a table model TV on the seat, a periscope sticking out of the top. Ooloorie guided it remotely, moving her “eyes and ears” around, peering critically over the shoulders of people who were her “hands.” There was no screen at her end, a tank of salt water twelve hundred miles away. The periscope cameras translated what they picked up into an auditory hologram, super-high-fidelity wave fronts that, to her, were “television.”

Cetacean scientists have a mildly condescending attitude toward humans. The text tells us that they consider us hasty and clumsy, always intruding on their pure serene contemplation of the universe by turning it into experiments and machines.

Given that history I alluded to, it would make more sense if they disdained humanity for being a bunch of cruel, violent savages. It could be a realistic issue for the NAC utopia to confront if dolphins only agreed to work with us reluctantly, while retaining a deep suspicion of our motivations. But maybe Smith would have considered that too on-the-nose as a piece of social commentary.

I told my story to the two scientists. Deejay listened with barely suppressed excitement. Ooloorie mostly in absorbed silence. “It grieves me to hear that Dr. Meiss is… is no longer…” struggled the porpoise. “He had an unusual mind for a landling and accomplished, by himself, much of what it took dozens to do here.”

As the text explains, Oolorie’s experiment accidentally established contact with Win’s world. While surveying it, they were able to communicate with Vaughn Meiss (whose murder kicked off the plot of the book). They gave Meiss enough insights that he could begin constructing his own Broach, which was a feat that impressed them.

This section, especially Oolorie praising Meiss as being able to do “by himself” what normally takes “dozens”, is an insight into how libertarians believe that science works. Like everything else, they have an unrealistic view of what a single person can achieve.

In the real world, science is a massively collaborative process, as in the famous quote about standing on the shoulders of giants. Great insights and revolutionary discoveries almost never spring from the mind of a single individual. It takes teams of dozens, hundreds, sometimes thousands of people working together, each one contributing a part to a greater whole.

This principle holds true even for people who are usually hailed as the rare geniuses who make great strides on their own. For example, Albert Einstein only nailed down the math for general relativity with help from his friend Marcel Grossman.

Thomas Edison, whose mythological status as a self-made man inspires libertarians possibly more than anyone else, had a large research team that worked under him, especially Lewis Latimer, who made critical contributions to the invention of the light bulb.

But libertarians dislike the idea of anything being collaborative. A goal that can only be accomplished by people cooperating makes them philosophically queasy. Instead, their ideology compels them to believe that all progress comes from geniuses working alone.

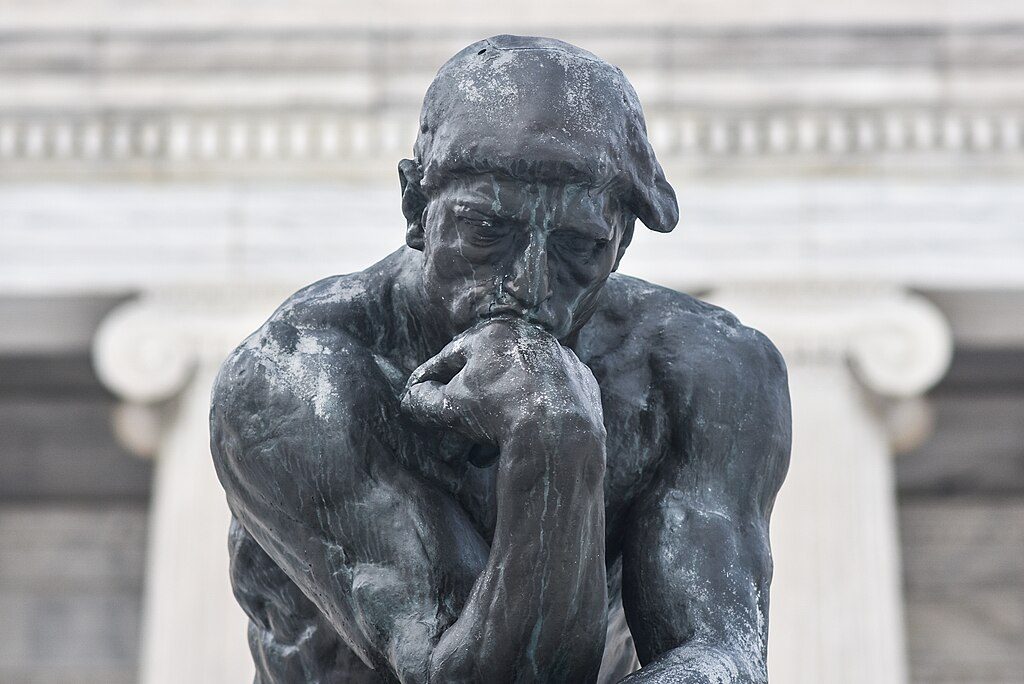

In Atlas Shrugged, for example, all of Ayn Rand’s protagonists possess a superhuman degree of competence. All they have to do is sit in an armchair and think, and they can come up with a brilliant idea that would never have occurred to anyone else. John Galt, the one ubermensch to rule them all, is so superhumanly competent that he can make devices which violate the laws of thermodynamics.

L. Neil Smith takes up the torch of this idea, depicting all progress—both in his anarcho-capitalist utopia and in “our” world—as owing to a few rare and exceptional geniuses. The only way TPB differs from Atlas is that it makes its everyman character, Win Bear, the point-of-view character, rather than one of the ubermenschen.

It’s no coincidence that libertarians keep doing this, and it’s not just because they’re allergic to the idea of cooperation. It feeds into their belief that these exceptional individuals aren’t just smarter than the rest of us, they’re better than the rest of us—and therefore should be allowed to do anything they please, without any pesky laws or other restrictions holding them back.

Image credit: Erik Drost, released under CC BY 2.0 license

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series: