The Probability Broach, chapter 14

Win’s investigation of the people trying to kill him has hit one dead end after another. The only remaining clue, extracted under torture from one of the hitmen, is that the ringleader is someone named Madison. He grumbles about this with his friends:

“Well,” I answered glumly, “how do we find this Madison character, put an ad in the paper?”

Deejay looked up from her steak. “That wouldn’t be John Jay Madison?”

“Dunno, honey,” Lucy replied. “All we know is he’s the brains behind Hamiltonianism here in Laporte. You know a Madison?”

“Not really, but there’s one giving weekly lectures in the History and Moral Philosophy Department. My engineers were talking about it—something about the War in Europe from the Prussian point of view.”

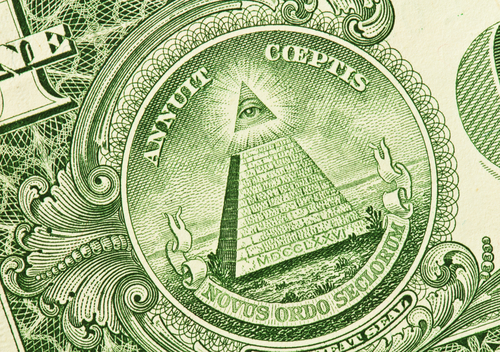

It turns out Madison isn’t only not hiding, he’s in the phone book. His name and address are listed there, cross-referenced with the name of his group, the Alexander Hamilton Society (which we know is the evil organization behind the attacks on Win, because the assassins wore jewelry with the eye-in-the-pyramid logo). Somehow, not one but two detectives overlooked that incredibly obvious lead.

Win, Ed and Lucy go to pay Madison a visit:

So it happened that we glided up to the front gate of a mansion that made even Ed’s place look seedy, a Georgian monstrosity with a dozen sequoia-size columns and twice that number of marble steps leading to the door. We were greeted by a huge uniformed servant with close-cropped steel-gray hair and the accent of a comic psychiatrist. “Herr Madizon vill meed you in d’Ogtagon Hroom. Bleaze vollow me.”

You’d think Madison’s unpopular views would make him a pariah (naming your group the “Alexander Hamilton Society” in this anarchist society is like naming your group the “Adolf Hitler Society” in our world), but that’s not the case. Somehow, he owns a mansion even larger and more extravagant than the ones Win has already seen, and he has actual servants.

Maybe Smith thought that it would risk making his villain sympathetic if he lived alone in a small, decrepit shack. Are we supposed to infer that the way he flaunts his riches is a sign of moral depravity, even in an uber-capitalist world like this?

Madison is a huge man, tall and muscular, with a nasty scar down one side of his face. Despite himself, Win finds him charming: “it was impossible to hate this man” despite the “blood on his charming, well-manicured hands”.

He greets them politely and asks what he can do for them, to which Ed bluntly replies: “We’re more interested in discussing what you’ve already done. Two of your people were killed attacking my house night before last, and another killed himself yesterday morning.”

Madison seems amused, saying that even if it happened, it had nothing to do with him or with the Alexander Hamilton Society: “We’re simply an institution for the discussion and debate of political philosophy.”

Lucy rejoins that if that’s true, it’d be the first time Hamiltonians confined themselves to debate. Madison is offended:

“My dear Judge Kropotkin. You’re remembering, perhaps, our brief tenure in the Kingdom of Hawaii—brought to an untimely end by the Antarctican unpleasantness? Or the savagery with which our proposed reforms were met on the Moon, afterward?” He looked at her more closely. “Or, if I’m not being indiscreet, perhaps even the Prussian War? Your Honor, all of that was long ago, and your concerns now are unjustified on several counts.”

Madison says that it’s true the Hamiltonians have waged war in the past, but they’ve learned their lesson from their defeats and now only seek to bring about peaceful change. He laments that there’s so much prejudice against them:

“[A]t various times in history, demagogues have required scapegoats. Unfortunately, we Hamiltonians have been handy on such occasions. It’s easy to condemn unworldly philosophers who have no ready means of reply. Since the Whiskey Rebellion, my fellows have been among the most unpopular in the world. What could we possibly say that would make people listen? How could we counter accusations graven in conventionally accepted history? Our views on economics and politics severely oppose the popular wisdom. Tell me, is that proof that we are wrong? To the contrary, it’s usually the other way around, isn’t it?”

“Very clever,” Ed said.

“And also very true. We believe that the good of society—in fact, the good of the individual—rests with recognizing and imposing an obligation to the state. We take what measures we can to transmit our views, hence this educational organization, my guest lectures at the university. But it goes very slowly: prejudice has such inertia.”

That’s true, of course. Conventional wisdom is often faulty and stubbornly resistant to change. Most people are set in their ways and refuse to be swayed by rational argument. While society as a whole does tend toward moral progress, it takes generations for new ideas to win out over old prejudices.

That makes it all the more bizarre that L. Neil Smith expects us to believe that Thomas Jefferson single-handedly talked the entire country into freeing the slaves, or that racism and sexism disappeared overnight when the federal government was abolished.

It seems that, in this book, prejudice only has inertia when it’s convenient for plot purposes. Whenever it would make his utopia look bad (say, for slavery to persist in an anarcho-capitalist paradise), people happily discard their bad beliefs as soon as they’re asked.

Remember, in the North American Confederacy, slavery is legal—not in the sense of “a written law says I can do this”, but in the sense of “if I’m powerful enough to do this, no one’s going to stop me”.

What if humans could be bought and sold in this world, just like any other commodity, and it was the Hamiltonians who were making the case to abolish it? What if they argued that we needed a centralized government to make and enforce laws protecting common people’s rights from the depredations of the extremely wealthy? (Which, needless to say, is exactly how abolition happened in the real world.)

That would be a genuinely interesting political debate for a novel set in an anarchist society. But it would create a level of moral complexity that Smith and other libertarians could never abide. Like Ayn Rand, he can only have a black-and-white political parable, where one side is solely made up of good guys who believe in freedom, and the other side is all mustache-twirling villains who want to create a brutal dictatorship.

New reviews of The Probability Broach will go up every Friday on my Patreon page. Sign up to see new posts early and other bonus stuff!

Other posts in this series:

To be fair this is a problem in the real world also. If your trying to form a large movement for something considered unacceptable by most people how do you go about it? If you just go just public and aboveboard then you can have more public impact if you can get attention but have trouble doing the things considered unacceptable. If you go secret you can do more unacceptable/immoral/illegal stuff but it is a lot harder to recruit and operate.

Many movement end up splitting into the public socially acceptable side and the more covert secret side. This doesn’t even have to be an evil group. The same thing happened to the abolition movement, with public anti-slavery groups protesting in safe areas and the underground railroad operating secretly.

If your going comic book level villainy you can be the leader of the public side and the secret criminal side at the same time.

Obvious example from the UK in my lifetime: Sinn Fein and the IRA.

I mean, there is a group called the Stalin Society in real life, which explicitly denies all of Stalin’s tyranny, so I don’t think that the name of Madison’s organization is that unrealistic.

Also, quite bold of you to think that Madison didn’t just inherit all his wealth from his ancestors. (Is he descended from James Madison? Surely it is not a coincidence that his surname is that of the father of the Constitution?) The man has servants, for God’s sake! If this is a world without oppression, how can there be servants? Even the villain couldn’t flaunt this in the open with no backlash if this were not tolerated, which can only mean that the NAC citizens all desire someone lower on the hierarchy to boss around. Smith must have been well aware that automation will not free people from drudgery for as long as capitalism endures. The mansion and servants also prove this is a deeply unequal society. So Smith knew inequality would persist in his personal utopia and did not care.

And Lucy’s last name is Kropotkin huh? Don’t tell me she is related to a certain anarchist communist… if so, the appropriation and post-mortem conversion of historical figures to something more ideologically acceptable to the author has crossed the line. This fictional society would have offended Peter Kropotkin to his core, and nobody who reads him could conclude otherwise. (At least the individualist anarchists are commonly but mistakenly believed to have been forerunners to propertarianism, but those same propertarians usually condemn Kropotkin as being no better than Lenin—a take that is utterly ahistorical—so Smith was either a dunce or lying deliberately.)

Also, though this is unrelated, it’s kind of a hack move to name your heroes and villains after historical figures in such a way to imply that they are playing out that ideological conflict again.

Unfortunately, you are missing the point bringing up how slow it takes the masses to change their views. Madison is meant to be seen as just as sleazy as Tucker Carlson or Grover Furr or Vladimir Solovyov. Even I can tell that his summary of Hamiltonian activities is not meant to be taken at face value. There is nothing they could say to make people listen, not because the world is prejudiced against them, but for the same reason that there is nothing that Nazis could say to convince the world they were not evil, after the death camps were liberated. Nazis can only gain popularity by sophistry and denial, hence the alt-right claim the mainstream media lies about them. A better analogy would be how nobody trusts tankies despite them being right about capitalism because their track record is always that they make a dictatorship when in power. From what I get of this speech, the Hamiltonians are terrorists. Madison doesn’t believe a word of what he said about moderation.

…so Smith was either a dunce or lying deliberately.

“Or?” Those two aren’t really mutually exclusive.

Minor spoiler – Lucy is the widow of Peter. Madison’s real name will be familiar to you but John Jay Madison is not it – he wanted to change his name to Hamilton but that would be too risky. So in effect, he wanted to change his name to Adolf Hitler, but knew that would be unpopular, so instead he calls himself Joseph Goebbels Himmler, and just runs the Adolf Hitler Clubhouse. Subtle!

So, is there any explanation of how the widow of a man who died of old age in 1925 is still alive in 1987 or whatever the year is? Let me guess, the NAC has super-advanced medicine that lets people live into their third century because potatoes.

(And I assume, then, that either she Anglicized her name–because “Kropotkin” is the masculine form and would not be used by a woman–or that alt!Kropotkin took an American wife, since there is no mention of Lucy having a Russian accent.)

I’ve said too much – I should let some things come as unpleasant surprises later on.

John Jay was also a founding father as well as James Madison. Jay was also a leader of the Federalist Party. The people in this world are obsessed with the colonial era.

I had to laugh about the phone books. Even back in the days when they were delivered to your door, people could pay to keep their data out of the phone book. That means that John Jay Madison isn’t hiding from anyone.

The Probability Broach is getting more and more unhinged as it goes along.

Overcoming prejudice against minorities/women/etc. doesn’t mean objectionable political movements with hideous ideas wouldn’t face stiffer prejudice. Madison’s the equivalent of the neo-Nazis who whine that a free society should be perfectly willing to discuss all ideas rationally, re-examine historical evidence for the Holocaust and so forth. Plus as Brendan said, he’s obviously insincere.

“You’re remembering, perhaps, our brief tenure in the Kingdom of Hawaii—brought to an untimely end by the Antarctican unpleasantness?” I imagine Smith doesn’t deal with the fact Hawaii was conquered, occupied and annexed by the United States in our timeline — sounds like in some fashion here we were greeted as liberators.

As to age, I believe someone mentioned in comments earlier that yes, there’s life-extension tech in this timeline, explaining Lucy being a WW I vet.

In relation to the Prussian war there is no way the libertarians would have won without an absurd techological like having post WW2 weapons and armour against Roman legions. A disorganised rabble will never beat an organised army of similar technology in a straight up war.

You’re totally forgetting The Magic of the Marketplace and the power of entrepreneurial genius unleashed! Geez, haven’t you read ANY Ayn Rand?! The organized army would depend on Brave Individualists paying taxes, so when they see how wunnerful the libertarians are, they’d just run away to Galt’s Gulch and the entire Prussian state would collapse in flames and anarchy!

No, I haven’t.

I value my sanity.

BTW, Galt’s Gulch would be in Switzerland, where the banks who finance all those Brave Individualists are. In a very secure gulch where those stodgy Federalists would never have the courage to hike.