When I was a kid I went through a period where I was interested in nautical disasters. Perhaps that has something to do with my general fear of being on a boat out of sight of shore.

I read A Night to Remember and I’m going to blame that book for my early interest in the topic of risk. And then I read about Lusitania and how the evil Germans sank that beautiful ship with a torpedo. I always remembered the part about where the Germans said “we won’t attack civilian ships unless they are carrying war material” and Lusitania was sunk, anyway. And the Germans, naturally, said there was war material on board but that was just a shabby excuse for sinking a luxury liner. It all sounded about right and that was my accepted reality.

I read A Night to Remember and I’m going to blame that book for my early interest in the topic of risk. And then I read about Lusitania and how the evil Germans sank that beautiful ship with a torpedo. I always remembered the part about where the Germans said “we won’t attack civilian ships unless they are carrying war material” and Lusitania was sunk, anyway. And the Germans, naturally, said there was war material on board but that was just a shabby excuse for sinking a luxury liner. It all sounded about right and that was my accepted reality.

The sinking of Lusitania was a very significant event, because it became the final excuse that the US needed to enter into the great European war. That was a decision of great consequence because it became the triggering event that turned the US’ gaze toward Europe, and put the country on a war economy. The Europeans invited a monster into their fight, and it grew out of all control and it’s been shambling around, ever since. “What ifs” are hard, but if the US had stayed out of WWI, the belligerents would have had to seek a political resolution, and there would have been no punitive Treaty of Versailles, and Adolph Hitler would not have risen to power on a tide of Germanic resentment. Of course, this is doing history wrong: we can point at big events like sinking the Lusitania and say “this was a turning-point” but we could just as easily point to some minor decision someone else made – Kapitänleutnant Walter Schwieger, who was commanding the U-boat – might have slept in, or mis-calculated the torpedo, or who knows what? For that matter, the people who assembled the arming system of the torpedoes might have been having a bad day and produced duds. The conceit of history is that we point at things and say “that is the decisive moment” but causality tells us that every moment is decisive, even the silly ones that seem unrelated and insignificant.

It’s interesting how a cloud has grown around that particular event. I pulled up History Channel‘s page on the event and it describes something different from what I remember: [history]

After World War I began in 1914, Lusitania remained a passenger ship, although it was secretly modified for war.

Oh, well that sounds pretty innocent, right? It’s not as though the ship was a Q-ship or anything. Lots of commercial ships were pressed into service hauling troops around.

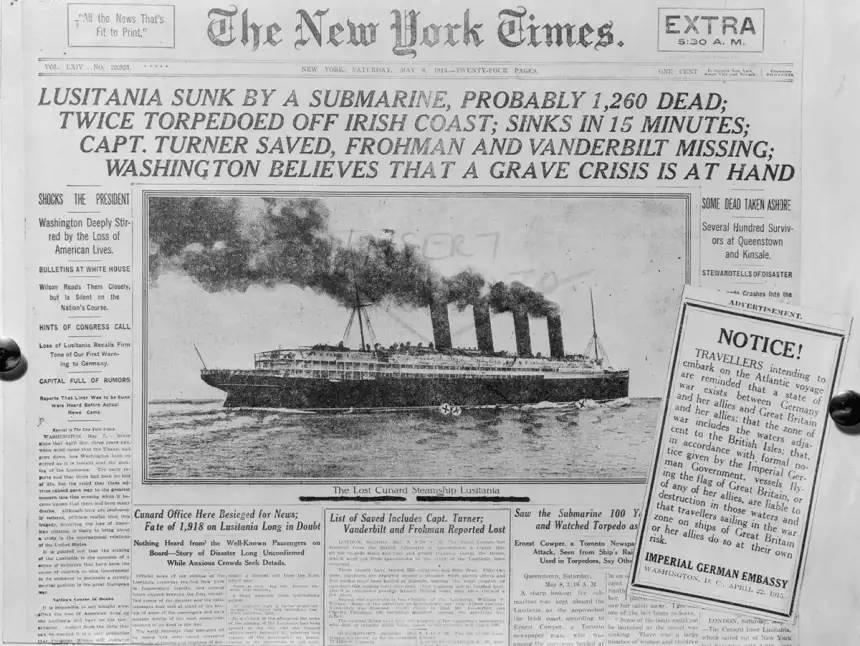

Days before Lusitania was scheduled to leave New York for Liverpool in early May 1915, the Imperial German Embassy in Washington D.C. placed ads in American newspapers reminding Americans that Britain and Germany were at war. They warned potential travelers that “vessels flying the flag of Great Britain or of any of her allies are liable to destruction” and should be avoided.

Right, so now the historical perspective has changed a bit. I forgot, somewhere along the line, that the ship was not an American ship. It was a British ship, and the Germans did try to warn that maybe it’s not a great idea to sail a luxury liner into a combat zone, flying the flag of a belligerent, even if it’s full of civilians. There were over 1,000 killed and only 120-odd were Americans. Some of those were Vanderbilts – so, technically, the Germans rid the US of a few oligarchs; they may have done a favor. But, the crowd was whipped to a frenzy of anti-German sentiment, there were anti-German riots (what is a “German” if they are living in the US?) and the US eventually entered the war.

As an aside: horrible asswipe Winston Churchill later said: “The poor babies who perished in the ocean struck a blow at German power more deadly than could have been achieved by the sacrifice of 100,000 men.” He was willing to sacrifice anyone and anything except his creature comforts.

That all lines up pretty much with the reality I understood as a kid; there was no need for a seismic shift when I read the History Channel description of the events. Imagine my surprise when I read that the British government officially warned divers exploring the wreck not to, you know, blow themselves up with all the ammunition [guard] And they still couldn’t resist the urge to lie just a little bit: “There was no high explosive” oh, right, well that’s certainly OK. But if there’s no explosive then why the warning? Because there is a fuckload of explosives, of course:

But Coombes added that a 1918 New York court case had established the Lusitania had not been armed or carrying explosives but did have 4,200 cases of small arms ammunition aboard. He added that the cases of cartridges had been stowed well forward in the ship, 50 yards from where the German torpedo had struck.

The “far away from where the torpedo struck” bit is an attempt to stall the questioning regarding what was believed, at the time, to be secondary explosions. And, I know you’ll be shocked to learn, it wasn’t just small arms ammunition: there were loads of shell fuses for 6″ gun shells, and probably much more. Divers on the wreck have recovered the fuses, but it’s quite possible there’s nothing particularly explosive to find because it detonated sympathetically when the torpedo hit. In other words, Lusitania was a death-trap carrying munitions for the war, using the passengers as human shields.

The 1915 British inquiry into the sinking of the Lusitania, chaired by Lord Mersey, barely touched on the issue. When a French survivor, Joseph Marichal, a former army officer, tried to claim that the ship had sunk so quickly because the ammunition had triggered a second explosion, his testimony was quickly dismissed.

Marichal, who had been in the second-class dining room, said the explosion was “similar to the rattling of a maxim gun for a short period” and came from underneath the whole floor. Mersey dismissed him: “I do not believe him. His demeanour was very unsatisfactory. There was no confirmation of his story.”

Let’s dismiss that testimony because his demeanour was unsatisfactory. Sure. But what he described quite accurately is small arms ammunition cooking off. And, in case you’re an American gun nut, let me assure you that 4,200 cases of small arms ammunition is “a lot of ammunition” by anyone’s standards. [Also: “small arms” designation can go up to some things that are really quite large]

Let’s dismiss that testimony because his demeanour was unsatisfactory. Sure. But what he described quite accurately is small arms ammunition cooking off. And, in case you’re an American gun nut, let me assure you that 4,200 cases of small arms ammunition is “a lot of ammunition” by anyone’s standards. [Also: “small arms” designation can go up to some things that are really quite large]

Does any of this matter? Well, yes, if you are like me and want to believe you have a view of historical reality. It’s a bit disconcerting to learn that, once again, the US entered a war under false pretenses. [The Spanish-American war, premised by the sinking of the Maine was also false pretenses] [The Maddox was not fired on by Vietnamese patrol boats; the patrol boats didn’t even exist] [And there were no WMD in Iraq] [And Bin Laden wasn’t in Afghanistan] I’m trying to update my historical reality with a new one that says that “Governments always lie when they go to war.”

Do we scroll that back to Augustine, and his stupid “Jus in Bello” argument that christians don’t go to war against eachother unless it’s a “just war”, which means that the other guy started it, or it’s for a good cause. It seems to me that the desire to fill Augustine’s criteria fits remarkably well with all the bullshit that governments spout – you know: “we’re here to help” aka “In order to help the villagers we had to shoot them all.” The facts of the world we live in is that governments are going to do whatever they want, and justify it with whatever fabrications are necessary to sell it to the gullible crowd. Augustine didn’t say anything about “just make shit up” but he probably would have, if he had gotten around to it.

The Lusitania was a mad fuck-palace for the upper class, unless you went down into steerage. It really was quite lovely. It seems to me that the British upper class mis-concluded “those Germans would never blow up a bunch of our rich people!” and that’s why they packed all the ammo below the water-line.

The Lusitania was a mad fuck-palace for the upper class, unless you went down into steerage. It really was quite lovely. It seems to me that the British upper class mis-concluded “those Germans would never blow up a bunch of our rich people!” and that’s why they packed all the ammo below the water-line.

Governments always lie

when they go to war. <– FTFYThe Lusitania was sunk in 1915, two whole years before the US entered the war. The sinking was important in forming anti-German opinion in the US, but did not lead to US entry into the war, in fact the Wilson administration worked very hard to ensure everyone they were still neutral and would remain so. Remember that Wilson ran in 1916 on staying out of the war. It was not until the Germans resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in 1917 that the US gave up on neutrality and joined in.

There was also the Zimmerman telegram.

Lusitania was part of the push for war. Anti-German riots were some indication of public sentiment (unless the riots were crisis actors)

Yeah, before USA entered WW I, it was selling a lot of small arms and ammo to at least the Russians (Winchester Model 1895 lever action rifles and Mosin-Nagant bolt action rifles, both in the Russian 3-line (0.3 inch) military rifle caliber as well as ammo for them), the French and the British.

Remington and Westinghouse almost went bankrupt when Bolsheviks refused to pay for the Mosin-Nagants after the revolution, but U.S. Government bailed the companies out by buying their stock of undelivered guns.

“What ifs” … According to what I found when reading up on this a few years ago, this was a close call.

The US was divided, with substantial pro- and anti-war factions: The Congress was divided, the people were divided, the military brass were divided, Wall Street was divided. It all came down in the end to Woodrow Wilson’s decision, and he chose to renege on his re-election promises and go whole-hog – having already acknowledged that war would militarize American culture permanently.

Elected and re-elected on a “Progressive” platform, Wilson pretty much ended what we call the “Progressive Era” in US politics. Clinton, Obama, and possibly Biden merely scurry beneath his shadow in that regard.

Let me see if I got this right.

So the German Empire was saying that any British or Allied ship was fair game. Munitions were irrelevant.

Whether or not the Lusitania carried munitions is irrelevant except as a German postwar excuse.

jkrideau@6>

hasn’t the U.S. made similar statements about Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, and other places?

and wasn’t that basically the excuse that Israel used for targeting journalist’s office space in the occupied territories more recently?

I feel like there may be some inconsistencies for how this standard is applied…

I don’t know.

First, deception is a first principle for warfare. The very first advantage any combatant seeks is surprise.

Second, in matters of national survival (France was very near losing the war), nations seldom really seek absolute virtue. More like Augustine who prayed ‘God grant me continence, but not yet’. Or, as one put it: ‘I seek to do right, but not right now’.

The question is not ‘was the Lusitania carrying munitions’ but rather if attacked or sunk can the Germans afford to reveal the methods by which they determined there were munitions on board. I suspect the reason they knew was some combination of educated guess, the ability to get munitions to Europe was a constraining factor in the continued survival of France against German offensives so the Brits and Americans were highly likely to use any shipping available but to do it as discreetly as possible, and well placed spies on the docks. The facts seldom play a major roll in anything but history books. The relevant part is, as with matters of law: what can you prove at the time.

This is poker, what do you know, what do I think you know, and, as with a “tell” or character clues, what insider information am I willing to let you know I know about. You make your calculations and place your bets. Play the hand, and either recover from the loss or capitalize on the win.

I don’t understand what he Germans were thinking. Clearly the Germans were not willing to reveal sources or mount enough of a defense to make the sinking seem entirely justified. They, seemingly assumed the facts, free of compelling and clear evidence, and the principle of the matter would carry the day. A major miscalculation.

Essentially they traded preventing less than a single days supply of small-arms ammunition and artillery fuses from getting to Europe for a major diplomatic loss that would, in time, be escalated into the US joining the war against Germany. The US was previously inclined to go that way but was being held back by isolationist sentiments. The Germans surely knew this, and yet, they took the risk. Perhaps they thought the great numbers of ethnic Germans in the US would tip the balance. At the time, from Chicago to Tennessee there was a swath of small towns so completely dominated by ethnic Germans that town business and trade was usually conducted in German.

Then again, perhaps it isn’t wise to assume the centrality of the sinking in shifting sentiment. The sinking, one of many, was on May 1915 and the US joined the allies officially in April 1917. A 23 month delay.

The Brits and Americans were clearly putting lives at risk but in the context of the war, where soldiers were dying by the thousands daily, it was such a big thing. Perhaps even a way for the British and American aristocracy to play their part. I don’t think anyone asked their permission to use them as human shields but, as pointed out, they were warned.

As an aside I wonder if there is a study to be done about links between Aristocratic deaths on the Lusitania, and Titanic 15 April 1912, and post WWI prosperity.

Interesting subjects.