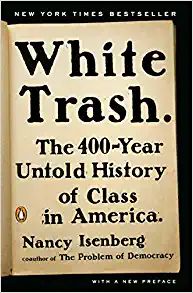

I have added another book to my recommended reading list [stderr] Nancy Isenberg’s White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America. In the last few months, I have gone backward and forward through it, trying to make sense of how the facts it exposes fit with my historical understanding.

If you pay any attention to US history, you know that slavery and racism are one of the supporting institutions that have defined and shaped the United States. You cannot understand the United States without understanding slavery and racism. But, that understanding has always felt incomplete, to me; I knew there was more. Obviously, there are details, but what is the big picture?

The history of the United States has become so repellent to me that sometimes I think I want to run away and join some organization dedicated to its overthrow. Unfortunately, that appears these days to be the republican party, and I don’t want a damn thing to do with them, either. I just wallow in futility (because the past is unchangeable, right?) and hatred (because the future doesn’t look so hot, either) But I want to understand; part of me clings to the idea that if we can all understand what happened, we can draw the venom from the wound and spit it out.

The history of the United States has become so repellent to me that sometimes I think I want to run away and join some organization dedicated to its overthrow. Unfortunately, that appears these days to be the republican party, and I don’t want a damn thing to do with them, either. I just wallow in futility (because the past is unchangeable, right?) and hatred (because the future doesn’t look so hot, either) But I want to understand; part of me clings to the idea that if we can all understand what happened, we can draw the venom from the wound and spit it out.

Yeah, that’s a terrible metaphor. This stuff upsets me and it makes me want to rage-smash things and whatever literary skills I have get compromised pretty quickly. If I do my job, today, in this posting, you may wind up feeling similarly.

The history of the US is the history of Racism, Classism, and Capitalism. “Capitalism” as it’s used by most Americans is a short-hand for laissez-faire capitalism – (French for “let it happen”, i.e.: no regulation) or anarcho-capitalism – the more unregulated and rapacious the better. It’s also called “entrepreneurship”, you know, when someone takes a woman’s child from her and sells them for a profit. Entrepreneurship. “Buy low, sell high” is the saying, and there’s no form of “buy low” that’s lower cost than flat-out stealing people or grabbing land that has been vacated through genocide. Jefferson changed Locke’s formulation from “Life, Liberty and Property” to “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness” which is a pretty thin fig-leaf, anyway, because Americans are socialized to conflate the accumulation of property with happiness. Jefferson might as well have said, “get some.” And I charge that these things are all tied together because the entrepreneurship of Americans is corrupted from its inception – even the pilgrims that disembarked from the Mayflower were quick to begin colonizing by the simple process of claiming the natives’ land. Naturally, that sort of entrepreneurship was accompanied by horrific violence; that’s generally the only way to get someone else to accept that kind of “deal.”

But, the other piece we don’t generally hear much about is that the settlers – the new Americans – brought with them a particularly toxic philosophy from England: classism. The colonists were quick to divide themselves in terms of class. And, since Europe was still in its monarchical stage, class division seemed to be part of the natural order. It was that attitude – that class is a part of a natural order – that set the North American colonies on the path to creating a class below the lower class: slaves. Classism was the norm in England, which was a hereditary aristocracy based on the principles that people had “good breeding” or not, that noble blood had some value. English society was full of tropes to the effect that common people were inferior (after all, the best way to promote your nobility as superior is to deride your commoners and poor as inferior to varying degree).

What Isenberg documents in painful detail is that the exercise of sending people to the North American colonies was a class-based exercise. England, for all intents and purposes, acted as though America was a ‘B Ark’ – a dumping ground for people of bad breeding, poor character, the shiftless and lazy. Right around when she explained that, was when the lights came on: the English hatred for poor people was exported – how could it not be? – as the few English upper class came over, and looked down their elegant noses at everybody. And the things they said about the natives (and later, the Africans who were imported involuntarily in chains) were unconscionable. At the time when this was happening, classist ideas of aristocracy and breeding literally gave creedence to the idea of “blood” and “birth” and people’s attitudes and behaviors were expected to be absorbed from their parents. Modern American ‘conservatives’ still carry forward some of this nonsense, with their ideas about “single parents” etc – bastardy, breeding, bad blood. I’m skipping ahead a bit, here, but when Americans got around to inventing scientific racism, IQ testing, and eugenics, one of the operating assumptions was that one’s parents had a tremendous effect on one’s post-birth nature.

Isenberg’s description blurs for me. It’s dense-packed and tremendously informative as she rattles through the history of some of the colonies and what horrific shit-heads their leaders were. For example, the crown governor who established the political framework for the Carolinas came up with a sort of ersatz aristocracy including titles (“Margrave” and “Cacique”) that sound like they’re right out of Skyrim. But these people were deadly serious, and slotted everyone into their frameworks. The events I am describing here are pre-“enlightenment” though even the “enlightenment” bit deserves scare-quotes because a lot of enlightenment political philosophy was attempting to bolster and explain class consciousness. The North American colonies were less republican than Rome, and Rome was very much a hereditary aristocracy. But Rome had more class mobility than the colonies. Think about that for a second. Rome had slaves, sure, but slavery in Rome was not even as bad as it evolved to be in the Carolinas. And the Roman citizen-farmer or citizen-soldier that Thomas Jefferson later came to extol the virtues of had more chance of upward mobility than a lower class North American.

One of the most unsettling aspects of Isenberg’s writing is that she keeps looping back to class terminology. The English, who sent people to the Americas, said openly that they were sending their trash. There were layers and layers of terms for calling people garbage of one form or another. Then, there were assumptions on top of that: garbage-Americans were necessarily stupid, and had stupid children, because they ate mud, or were bastards, or lazy, or poor. It just goes on and on. The English were seething with hatred at their poor and lower class, so they stuck them onto the American ‘B Ark’ and sent them to where they could be forced to work because the alternative was to die. There was a lot of that. And women, and cows (the lowest class of both) were sent over as live-stock to breed with and maintain a permanent underclass. It’s not hard to see how slavery just naturally fit right into that structure.

Americans didn’t seem to have a lot of self-awareness. Isenberg doesn’t mention this, but Ben Franklin, who she discusses a great deal, went to Paris and was considered to be a horny, stinky, freak by the French upper class, who literally expected him to act like some kind of dancing bear in their salons. And, he did. So did Jefferson. Both of those men felt that they were sophisticated and worldly, but Franklin was visiting the Paris of Voltaire, compared to whom he came off as a trained ape of some low sort. It appears to me that Franklin and Jefferson both felt they were received as equals because they had a lot of sex with the edgier set of French mesdames, but my suspicion is that it was more likely that one of the grand dames dared her chambermaid to fuck the disgusting American to see if she could stomach it. Franklin wore a raccoon on his head. In Paris. The cultural center of the world. Yet, Franklin and Jefferson both had this gigantic streak of ignorant hypocrisy that could only spring from deep lack of self-awareness. Franklin’s writings contain many instances, quoted by Isenberg, of his deriding people as lazy, debtors, who didn’t know their place – yet his embassy to Paris was viewed somewhat as the Romans viewed Caligula’s horse who was elected to the senate. They didn’t even have to dig into Franklin’s absurd history of running away from debts, while later fulminating about debtors. Franklin and Jefferson were, in the true fashion of American hypocrites, everything they professed to hate, with the addition of an unaware stupidity that made them incapable of realizing it.

My current take on racists and classists is: 1) both ideas spring from a common error, that there is a “nature” that is more powerful than cultural “nurture” and 2) they are profoundly stupid, because you cannot be anything other than intellectually lazy or stupid to be able to hold racist or classist views without seeing their open contradictions. How could any white person think, as so many did, that black people were inferior, when confronted with a self-taught orator in the form of Frederick Douglass? “I hear he’s doing great work these days,” said Donald Trump, whose idea of “oratory” would doubtless elevate Tucker Carlson to the status of a silver-tongued genius. Perhaps the spice in Trump’s hatred for Barack Obama is that Obama is better at everything Trump ever did than Trump, and he was effortlessly cool about it the whole time. That does kind of jam up your sense of superiority if you’re a white supremacist and you can’t spell or read and there are black orators like Obama and Douglass who effortlessly slapped away the best that white America has to offer – let alone Donald Trump.

It is surreal to read the bits that Isenberg quotes from Franklin, and to realize that the old gomer actually believed that shit, in spite of the fact that he was a living contradiction of his own values. How was he taken seriously? Because, among Americans, he was educated and energetic and erudite. What a sad man.

[Jefferson] allowed his sheep to graze on the lawn of the president’s house, letting everyone know that a “gentleman farmer” occupied the highest office in the land.

Jefferson may have hated artificial distinctions and titles but he was quite comfortable asserting natural differences. With nature as his guide, he thought there was no reason not to rank humans on the order of animal breeds. In notes, he wrote with calm assurance, “the circumstance of superior beauty is thought worthy of attention in the propagation of our horses, dogs, and other animals,” with emphasis he added, “why not in that of man?”

Careful breeding was one solution to slavery. In his revisal of the laws, Jefferson calculated how a black slave could turn white, once a slave possessed 7/8 the taint of his or her African past was deemed gone.

It’s not just stupid racism; these stupid racists really believed they were superior. In order to believe that, they had to forklift in this creaking edifice of class consciousness that ratified their sense of superiority – allowing them to ignore the obvious fact that they were just more ruthless opportunists than the other guys. Jefferson appears to have really genuinely believed that there was something wrong with the slaves that stopped picking cotton as soon as they were allowed to. What did he expect, that they would cheerfully work harder? That’s stupid. These people were the spiritual ancestors of today’s dumbass conservatives like the eminently punchable Tucker Carlson wondering what’s wrong with kids today, that they don’t want to try to get ahead by plunging into a job market that is designed to grind them to bits. Or later capitalist hero Andrew Carnegie, who wrote a whole book about the virtue of hard work, while sitting at his sumptuous desk at his huge estate while lower class immigrants who had come to America because the alternative was starvation, fed his steel mills. Carnegie was a capitalist, and an entrepreneur, to be sure – but most of all he was a ruthless opportunist. And, he wrote a whole book about the virtue of hard work while, as one of his union workers said, “the closest he’ll ever get to a blast furnace is when he dies and the devil takes him.” American laissez-faire capitalists used the same dodge that the slave-owners did to make themselves feel justified: they blamed their victims. That great American tradition goes right back to the pilgrims (who were a warped bunch of authoritarian religious bigots) who immediately hated the natives because the natives appeared to be so lazy they were enjoying a splendid life hunting, fishing, fucking, and fighting with their neighbors, on a truly beautiful patch of land. The natives thought the colonists were crazy, and the colonists – through their class-sensitive eyes – thought they were lazy. And laziness is the devil’s hand, or something.

In my review of Ramp Hollow [stderr] I commented at length about how eye-opening it was to see that taxation was used as a way of moving appalachian subsistence farmers off their farms and into factories, where they could make wealth for capitalists. After all, you can’t make wealth for capitalists if you’re a subsistence farmer who doesn’t need a government – you’ve got some pigs and a still and some land in corn and some wheat and you can trade with the neighbors for goods and services. Isenberg shows me what I missed: we have to deride those people as “mudsills” and any of a dozen English terms for “garbage” because they aren’t part of the economy and Thomas Jefferson needs workers!

Isenberg does a great job of explaining how the pilgrims’ lock on the colonies’ economy was not just religious – it was practical and governed land ownership, loans, trade, and business relationships. Being a quaker was a way of cementing yourself into the class hierarchy in Massachusetts or Pennsylvania. Once you were in, though, you could use the rungs of the church to seek status, using the usual web of religious ass-kissing and “putting in your time.” Franklin, who danced in and out of the Quakers’ religion was opportunism, and he saw the Quakers as a path for increased class status.

Though Jefferson sold Europeans on America as a classless society, no such thing existed in Virginia or anywhere else. In his home state, a poor laborer, or shoemaker, had no chance of getting elected to office. Jefferson wrote knowing that semi-literate members of the lower class did not receive even a rudimentary education. Virginia’s courts meticulously served the interest of rich planters.

And wasn’t slavery a “distinction between man and man?” Furthermore, Jefferson’s freehold requirement for voting created “odious distinctions” between landholders and poor merchants and artisans, denying the latter classes voting rights. One has to wonder at Jefferson’s blatant distortion, his desire to paint the society of cincinatti as so otherworldly to Americans that only extraterrestrials could appreciate it. Many elite Americans were fond of the trappings of aristocracy.

There is one part of the puzzle that remains undiscovered, for me, and that is an ancient one: why do the rich so often hate the poor? I suspect Epicurus was right: they are seen as a threat. The American colonies were built by England flushing their poor, as they did again to Australia, later. Isenberg presents us with an entire catalog of the nasty terms the English used for their lower classes, and illustrates how they changed and became specific to the colonies – but the basic hatred for poor people remained.

Perhaps another explanation for why the rich hate the poor is because the rich person’s main way of getting rich(er) involves cajoling, clubbing, or economically compelling the poor to work for them. Then, as now, the true miracle of capitalism was how 1% of the population got the other 99% to work themselves to death, for them. The social shackles that enforce that are complicated and their mechanism is deliberately obscured, but in the colonies, it had a lot to do with setting a lower class against itself, encouraging poor whites to hate black slaves, and vice versa, while the benefactors of the system sat comfortably in mansions, hating all of the lower classes. “Divide, and rule” indeed.

It’s a dynamic we are stuck with, today. Policies in the US that are not racist are often classist, which has the same effect at the bottom since the classes are reinforced along racial lines. It hardly matters whether Mitch McConnell is refusing to help black people, or refusing to help poor people – he’s going to refuse both categories. The United States oligarchy thus slides seamlessly between racist hatred and classist hatred, without having to directly acknowledge either. You can see that in the racist vote-suppression efforts going on nationwide, and the refusal of congress to help the non-working poor while offering pathetic bail-out scraps to the working poor.

It’s hard not to wander all over the place while I think about this stuff (I feel this is one of my less coherent postings) but that’s the effect White Trash has on me. As I go through it, I feel like there are so many pieces of the puzzle dropping into place. If you’ve been reading American social history, such as Howard Zinn, or anything about the Whiskey Rebellion, Ramp Hollow, the mining wars, 1493, The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, or anything that touches on how the colonies’ economies worked, and why the revolution and the civil war happened – White Trash is an essential puzzle-piece in your big picture. The big picture, of course, is shame piled atop shame.

Highly recommended.

Interesting. Thanks!

Excellent essay, Marcus. My only quibble (and one I am very guilty of, even being a member of the plebes myself) is it not only the “conservatives” who despise the poor. Even as I vocally agreed with Hillary’s sniffy dismissal of “the deplorables”.*

(*Are the deplorables simply an example of Marxian “false consciousness”?)

“Americans didn’t seem to have a lot of self-awareness”

LOL at use of past tense.

“It hardly matters whether Mitch McConnell is refusing to help black people, or refusing to help poor people”

It matters a great deal. The latter allows him to deny racism (with some justification). Also, it has the added benefit of making black people and SJWs cry “racism”, which any poor white person can reasonably hate them for, given that they’re getting it in the neck too but are too melanin deficient for anyone who reads the Guardian to give a shit. Divide and rule again, with the *active* help of the so-called Left. (echoing reference to “deplorables”, although Clinton is not what any European would call left)

“came off” to whom; the French of the time, or to you? My impression is that he was genuinely admired by the French, and Voltaire in particular, as a scientist and diplomat.

It’s no mystery why the rich despise the poor; it’s the obvious rationalization technique to justify why it’s ok that they have while the poor have not.

“why do the rich so often hate the poor?”

Why does anyone hate anything?

“I suspect Epicurus was right: they are seen as a threat. ”

Bingo. We only hate what we fear, and we fear what has the potential to change our lives. The change might be good or bad, but we fear it being INVOLUNTARY.

I have long felt that the myth of the brave and hardy pioneers who pushed west was flawed. That what really happened was that the shit where they were was drowning them and they moved to west to cleaner pastures. Existing inhabitants? Kill them or drive them out. Getting shitty again? Move west again kill or drive out the inhabitants. Rinse and repeat. Add to that the reality that the major benefactors were the oligarchy. They ran out of territory at the west coast.

I have decided that as wonderful as all the political and economic system concepts look on paper, they all fail when people are added. Only a hybrid system that can control the level of individual political power and wealth accumulation might work but I cannot articulate exactly what that would look like.

Practices, and perhaps attitudes, changed in England after the Black Death. Suddenly peasants and workers, because their numbers had decreased, were not tied to the land, but were able to move about in search of better pay and economic opportunity. Vagrancy laws were passed to prevent that. In addition, the gentry were permitted to employ craftsmen and artisans by force of law for a period of one year at pre-pandemic wages. Giving alms, which had been a religious duty, became illegal except when the beggar was disabled or over the age of 60. OC, begging was also illegal except in those cases. This may have been the origin of the idea in England of the deserving poor. The enclosure of the commons came later.

Niall Ferguson, if we can trust him, says that the English colonies were more egalitarian than the Spanish and Portuguese colonies, because the latter brought over the padron system. That is one reason, he says, for the economic dominance of the US and Canada.

My sociology prof was fond of saying about America, “When you control for class, race drops out.” Things are not so neat, IMO, but the two are closely intertwined. It also seems to me that racism has been used as a wedge to divide the working class. Even in slavery times you had the White mudsills looking down on the slaves, and sometimes vice versa. Racism still has that function today.

> Being a quaker was a way of cementing yourself into the class hierarchy in Massachusetts or Pennsylvania

Are you sure about the Quakers being a part of the acceptable class hierarchy in Massachusetts?

My understanding of it was the early Quakers left Massachusetts for Rhode Island, and later to Pennsylvania, due to persecution from the Puritans in Massachusetts.

Is there anything in there about how classism developed in the first place?

Part of it, I think, is based on what Jefferson was saying about animals. At a time when practically everybody was a farmer tinkering around with animal husbandry, where breeding dogs and chickens was commonplace, it would make sense to imagine you could do the same with humans. If you start with the faulty premise that the wealthy are smarter, then of course you would try to breed for that intelligence in humans (and note all the husbandry terms in classism, even the terms the wealthy used for themselves like”breeding.”) Social Darwinism long predates Darwin.

But the other big part, I think, is that for many centuries, monarchies and aristocracies were kind of necessary, at least in Europe. After I retire I’ve been thinking of writing a book on the history of liberalism from a social evolution perspective, based on the following premises:

1) Societies and cultures have been engaging in warfare since the dawn of history, and it’s hard for us moderns to imagine what it would have been like to always know for a fact that there were people within a few weeks’ march from you who would, if given the opportunity, love to enslave you and take all your stuff.

2) That constant conflict created strong evolutionary pressure on societies to adopt cultural practices that let them prevail in the struggle. Note: I’m not talking about evo-psych, where peoples’ brains are supposed to be changing over many generations. I’m talking about “Our neighbors are doing something new, and we need to either copy it, come up with something better, or get conquered.” Call it the Sid Meirs Civilization view of history.

3) If a trait or meme shows up over and over in many different societies, the default assumption should be that it provides them with some competitive advantage in these long term struggles. (see for example: religion)

4) Memes that help their societies will tend to develop other ancillary memes that help promote and maintain them. (also see religion)

5) Technological advances can eliminate the advantages that certain practices create. However, their ancillary memes can cause these practices to stick around for centuries after they are no longer useful.

6) Liberalism is the process of clearing away memes that have outlived their usefulness.

Hereditary monarchies and aristocracies are, I think, the perfect examples of this theory. Hereditary monarchies are actually pretty awesome if you don’t want to have a civil war among your nobility every time the leader dies – and societies that have civil wars all the time tend to get conquered by societies that don’t. And in Europe throughout the feudal period, the entire military system was based around having an aristocracy, because maintaining a horse and armor and trained soldiers was expensive. The societies that survived were the ones where a king could send out a letter to his nobles and say “You must show up at Bristol on June 7 with X number of troops behind you,” and the nobles would actually show up on that date. The societies that weren’t able to do that got conquered by the ones that were.

But then, gunpowder led to standing armies, because you didn’t need to be rich to shoot a gun, and suddenly having all those rich people around owning all the land wasn’t that much of an evolutionary advantage any more. And then things like rising literacy and newspapers made democracy possible, which was even more stable than hereditary monarchy. But all the ancillary memes that had supported classism (“divine right of kings,” “noble blood”) weren’t going to just disappear overnight – they would stick around for centuries, and of course the struggle against them is ongoing today. Classism became dead wood, and liberalism is the process of clearing away the dead wood of history.

There can be various reasons. Here’s one. Imagine a rich white dude who wants to publicly beat up a cute child. Normally his peers would criticize his actions, because the kid is cute and evokes protective instincts from people. Now imagine the white dude convincing his peers that the cute kid is actually lazy, with bad blood, from a prostitute mother. Now he can beat up and enslave the kid without earning his peers’ condemnation and without risking any cognitive dissonance (remember, our white dude wants to pretend that he is a good man, and good men can abuse others only when the victim “deserves to be abused”).

Think about the Holocaust. First, for several years Hitler ran a propaganda campaign that was designed to convince Germans that Jews must be hated. Only afterwards he started killing Jews. If Hitler had suggested killing Jews on day one without any prior propaganda, Germans would have objected to killing their Jewish peers for no reason.

In order to exploit and abuse some group of people, you must first delude the society (and maybe also yourself) into believing that these people are bad and deserve all these bad things you are doing to them.

The idea that “white trash” automatically equals poor is laughable, as the white-trashiest people I’ve seen are all rich af. It ain’t about money, it’s about behavior.

WMDKitty: A particularly well known example of “white trash behavior” is exhibited by the entire clan currently (for the moment, let’s hope) in the White House!

Marcus: I would love to see you turn your gimlet eye and respond, maybe in a separate post of your own, to Brucegee’s interesting post.

I’d love to hear what Marcus or anyone else has to say about my post.

As an aside: if there are any other Downton Abbey fans here, there were some people who thought the show was just nobility porn, but I got something else entirely out of it. It seemed to me that a main theme of the entire show was the hereditary lord trying to prove that he wasn’t a parasitic leech on society, and failing at every turn. In World War I he tried to take the medieval route — hoping to go to France and lead troops in battle — only to be told in no uncertain terms that the military had no use for him other than as a fundraiser. Then after the war he tried for the 18th-19th century justification for the nobility — that, because he was an aristocrat and thus supposedly smarter than everyone, he ought to have a position in government and/or finance — an idea that was sabotaged because he was kind of an idiot. (“This Ponzi fellow has a fantastic investment opportunity!”) So then he went to a more 20th century justification — “I’m providing jobs for all these people!” — except as they moved into the 20s, nobody wanted his crummy service jobs anymore. So finally, by the end, he was settling into more of just a landlord/farmer role, and there was some pretty clear indicators of how his daughter would fill the modern role of the aristocracy, a kind of glorified museum curator.

@#5: Rob, I agree with you. A biography of Franklin by Walter Isaacson says the same. It seems that the French found his bucolic ways endearing, and greatly admired his intellectuality. @#10: Patrick is correct. In his book, “American Political Writers, 1588-1800”, Richard Amacher talks of how Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson (and the Quakers) were driven from the Massachusetts Bay Colony because they differed in their interpretation of what was the source of God’s revelation. The Puritans considered them heretics. Finally, I think the rich hate the poor because they fear the poor will try to take away their wealth. To me, this may be an implicit admission of guilt at having too much and not sharing. To assuage this guilt, they must demonize the poor in order to justify their selfishness. Just a guess.

American political parties today: The Republican Party is racist, the Democratic Party is elitist. The Republicans are elitist, too, but they are happy to embrace lower class racists.

As for the emergence of class, IMO, it was the result of the Agricultural Revolution. That made for the ownership of land, and that made for helotry. Before the French wiped them out, the Natchez Indians has four classes: the Suns (royalty), the Nobles, the Honorables, and the Stinkers. About half the population were Stinkers.

My impression of Franklin in Paris is probably wrong; I was going by other historical attitudes I knew about in 18th-century France. Still, there’s a lot to read between lines – it does still sound to me as though Franklin were treated as a bit of an oddity – and, in 18th-century France that would be contextualized in class terms. Everything was, so that’s not a bold claim. They patronized everyone.

https://theamericanscholar.org/franklin-in-paris/ appears to be a fair description of how Franklin was received. Like most things I’ve read about Franklin, it comes across to me as waffly.

I’m probably blinded by my loathing of the US founding fathers. Franklin was not as bad as the rest, but he seems to me to be a jerk. Now I promise I will absorb a biography of him.

I suspect that classism wasn’t exactly an English invention. A Distant Mirror (by Barbara Tuchman), describes the attitudes of 14th-Century French nobility towards commoners, and it’s at least as bad as anything described in the OP.

Continental Europe also had a well-developed classism. In fact, in German, at least, there were special pronoun usages to mark when was speaking to an inferior. (I remember noticing this in the play Woyzeck.)

Sorry about the delay getting back to this thread. There are thoughtful comments here that deserve a response, but I was goofing off for the holidays.

Let me see if I can catch up.

sonofrojblake@#3:

“Americans didn’t seem to have a lot of self-awareness”

LOL at use of past tense.

I don’t want to get in the habit of lying to The Commentariat(tm) but it’s really tempting to say, “I did that deliberately.”

Robert Estrada@#8:

I have long felt that the myth of the brave and hardy pioneers who pushed west was flawed. That what really happened was that the shit where they were was drowning them and they moved to west to cleaner pastures. Existing inhabitants? Kill them or drive them out. Getting shitty again? Move west again kill or drive out the inhabitants. Rinse and repeat.

There’s a lot to that. The frontier served as a kind of safety-valve for the colonies; they could send their more belligerent citizens out to west and had a good chance of never hearing from them again.

I’m endlessly fascinated by the idea that people lived in a time when you could easily go a few days’ travel, change your name, appearance, and accent, and pretend to be someone else. Nowadays, establishing a new identity is a lot of work and the identity probably doesn’t hold up to scrutiny (especially if you have no fully-fleshed out past) but back then, you could shit the hot tub pretty severely, then change your name, go out west, and start the process all over again. [There’s an interesting story behind how credit rating bureaus came into existence, specifically to stop that kind of grift]

brucegee1962@#11:

Is there anything in there about how classism developed in the first place?

I’m not sure if I should respond to this as a separate posting, or as a comment.

The short form is that England was the most classist civilization on Earth, at the time, and exported it to the colonies with the people. At the top of the class heirarchy they sent upper class adventurers who wanted to be colonial governors, and at the bottom they sent poor people who were sometimes literally rounded up and stuck on a boat with no idea where they were going. The upper class toffs wanted to establish a civilization they were familiar with, which was England – class divisions and all. The lower class… Well, what they wanted was, as always, irrelevant. Although, as I pointed out in my post about Ramp Hollow, the upper class immediately began maneuvering in order to maintain class hierarchy – subsistence farmers were a threat to them, so they began establishing systems of taxation that broke the farmers’ ability to exist without money – which pulled them right into the economy. [stderr] The villain of that story, by the way, was Alexander Hamilton.

Social Darwinism long predates Darwin.

An important point, worth repeating.

The notion of aristocratic blood-lines goes back to prehistory; I suppose every thug-king who tried to put their frogspawn on a throne was practicing social darwinism. Again – they had to convince themselves that it was justified that their child should rule, so they had to make up elaborate fantasies about blood-lines (and divine right to rule…) in order to keep the peasants in line. “Aristocrat” is rooted in the term for “excellent” – then, as now, aristocrats thought they were the best sort. Good breeding, etc.

But the other big part, I think, is that for many centuries, monarchies and aristocracies were kind of necessary, at least in Europe.

In the sense that any European civilization found itself surrounded by monarchs and aristocrats, who would conquer them if they couldn’t defend themselves. I think it’s pretty clear that Rousseau was wrong: there is no “state of nature” in which people lived comfortably in the woods without government and property and war – it appears to me, as you say, that those things co-emerged with civilization.

My guess would be that aristocracy, armies, and kings all started along with agriculture. When you’ve got farmers and beer-makers and food stores, they are a prime target for raiders, so you need some organization to defend them. That turns into a class heirarchy (and parasitic religion comes along to feed off it and rationalize it). Agrarians without organized defenses are just lunch-meat for raiders.

1) Societies and cultures have been engaging in warfare since the dawn of history

2) That constant conflict created strong evolutionary pressure on societies to adopt cultural practices that let them prevail in the struggle.

3) If a trait or meme shows up over and over in many different societies, the default assumption should be that it provides them with some competitive advantage in these long term struggles.

I’m with you so far, 100%. I’d replace “dawn of history” with “dawn of agriculture” though the two are synonymous – you need an agricultural civilization to produce the kind of surplus necessary to have monarchs and scribes or historians. A civilization has to have surplus to make it an attractive target (other than for slavers) for raiders.

I wish there was some terminology that worked instead of evolutionary terminology. I forsee that some people who lean toward social darwinism or evolutionary psychology might start to muddy the waters.

4) Memes that help their societies will tend to develop other ancillary memes that help promote and maintain them.

Agreed, though I don’t like memeologic terms. I prefer “idea” but it’s the same (which is why I prefer “idea”) or perhaps “cultural artifact” or something like that.

5) Technological advances can eliminate the advantages that certain practices create. However, their ancillary memes can cause these practices to stick around for centuries after they are no longer useful.

6) Liberalism is the process of clearing away memes that have outlived their usefulness.

#5, I can buy, but #6 doesn’t sit well for me. I think “liberalism” (whatever that is) has a broader agenda. It encompasses skepticism about society and heirarchy. The Enlightenment, after all, can be seen as not much more than a reaction to authoritarianism, occurring around the same time (coincidence?) as Louis XIV perfected absolute monarchy in France, and French Catholicism tightened its grip on society to the point where it came to own a large percentage of the lands that the crown didn’t. In a sense that can be seen as a “war of ideas” but that seems to make ideas more important than they are. “Broad cultural trends”? I don’t know the words for this. “Politics” perhaps? You’re getting close to pulling a Von Clausewitz: “Politics is just a continuation of civilization by other means.”

It’s almost as though we need Hari Seldon from Asimov’s Foundation series to give us the terms for some of this stuff.

Hereditary monarchies are actually pretty awesome if you don’t want to have a civil war among your nobility every time the leader dies – and societies that have civil wars all the time tend to get conquered by societies that don’t.

There you’re picking at one of the foundations of civilization: the relationship between civilization and warfare. In my mind, that relationship is so tight that they are almost interchangeable – a civilization that cannot defend itself ceases to exist, and civilization is the organization of mutual defense for agrarians. I keep coming back to the rise of agriculture because that’s where civilizations come up with the idea of “this is our land” and dots on a map that must be defended.

And then things like rising literacy and newspapers made democracy possible, which was even more stable than hereditary monarchy.

Hang on hang on hang on… You’ve got Athenian democracy, and the Roman republic stuck somewhere in there. I think you can make a good argument that those states were successful because they organized warfare effectively, although Darius of Persia would disagree and say the Greeks got lucky.

But all the ancillary memes that had supported classism (“divine right of kings,” “noble blood”) weren’t going to just disappear overnight – they would stick around for centuries, and of course the struggle against them is ongoing today. Classism became dead wood, and liberalism is the process of clearing away the dead wood of history.

I agree there. Class consciousness appears, to me, to be a confusion between nature/nurture, as usual. The Romans actually were pretty good about adopting promising young people into the great families (it’s one way to keep a great family great!) though the quintessential examples of aristocracy shitting the hot tub are the crime family that ran Europe for so long – it blows my mind that Alexander of Russia, George of England, and Kaiser Wilhelm were all cousins. Setting aside Asia, most of the world was being run by the same inbred twits. If there was ever an argument against aristocracy, it would be Kaiser Wilhelm.

WMDKitty — Survivor @#13:

The idea that “white trash” automatically equals poor is laughable, as the white-trashiest people I’ve seen are all rich af. It ain’t about money, it’s about behavior.

Sort of. It’s all tied together, isn’t it? I’m sure the Astors of New York would tell you it’s got something to do with breeding; they resolutely looked down their noses at the merely wealthy “nouveau riche.”

One of my father’s French friends (an old-school aristocrat with very very blue blood) referred once to a French president as “Le Baron De Bic” – implying that the fellow had made a fortune selling ball point pens, and was new money. Even the Romans had a term for new money, “New Man.” It wasn’t entirely behavior.

The Astors would still be sneering at the Trumps. They would always sneer at the Trumps.

Andreas Avester@#12:

In order to exploit and abuse some group of people, you must first delude the society (and maybe also yourself) into believing that these people are bad and deserve all these bad things you are doing to them.

Quoted for truth.

[I think you have to delude, especially, yourself. There appear to be very few self-actualized nihilists in politics, yet the US Congress is full of people who’ll cheerfully shit on the poor. The problem with not hiding your attitude, if you’re a nihilist, is that you’re effectively declaring war on the poor, who can effectively declare war on you right back. So the ‘conservative’, or whatever they want to call themselves, politician has to come up with a smoke-screen to hide their hatred.]

margrave (wiktionary):

A-ha. Carolinas; Carolingian. Dude had a historical sense of humour.

Cacique (wiktionary):

Yet another appropriation of Native culture.