Let me encourage you to do something odd.

I’m 57 now and I sometimes forget things. We tend towards dementia in my gene-line, so I worry that some day my memories may begin to shred and blow away and I’ll have to rely on what other people remember of me; that’s why, in 1991, I started getting serious with a camera, and have been snapping away cheerfully ever since. I’m not particularly worried (because: worrying does not help at all) but I’ve always supposed that if things came to it, I might wind up in a rocking chair someplace, rummaging through an archive of photographs, clutching the straws of my life close to me at the end. In the last decade I’ve lost a few important people out of my life, and none of them – not one – has said on their death-bed, “I wish I had spent more time in Marketing status meetings.”

If the existentialists are right about anything, it’s that we are what we do. Which means that what we’ve been is what we’ve done. As a nihilist, I am unconvinced that there is any “meaning” – define that as you will, since I am rejecting the term – to life; but if there is any, it’s the things that we feel are important to us. In other words, the “meaning of life” is a personal experience, to me. You will, naturally, have a different meaning. But the meaning of my life is the things I have made with my hands, software I have written, businesses I have built, problems I have solved, people I have known, kisses I have shared, food I’ve cooked, museums I have wandered through while holding hands and commenting on the art – thousands and thousands of bits of meaning, fractally detailed, and easy enough to forget.

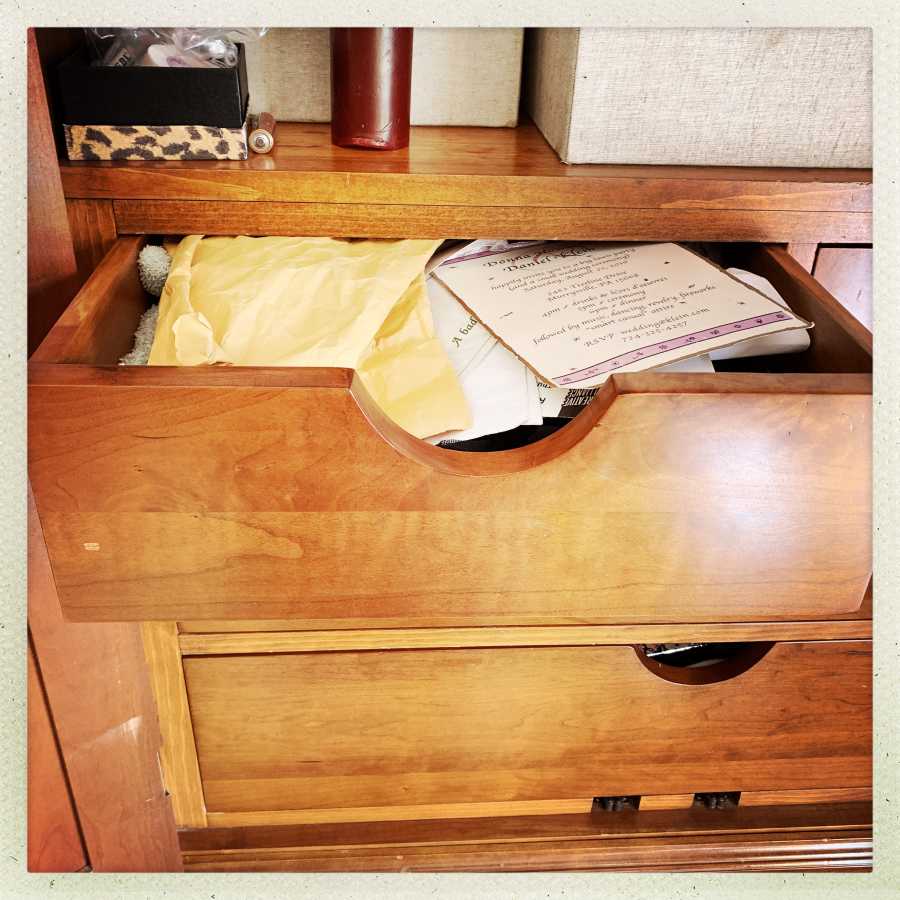

That is my memory drawer. Things that remind me of moments that I never want to lose; they’re all jammed in there with no organization (I consider that a metaphor for life) – I sometimes pull the drawer out and rummage through it. As I do so, memories cascade through me and even the bad ones are good, since they are what gives form, shape, and meaning to my life. Everything is recognizable, immediately: see the blue fuzzy thing on the left? That was my puppy’s toy when I got him from his mama. Oh, and right on top is the invitation to Dan and Donna’s wedding! Just to the left (the piece of paper saying only ‘A bad’ but otherwise hidden) is the programme from a concert in a park in San Diego that Click Hamilton put on when I came to visit; he had a local violin prodigy come and play and the whole park shut down and gathered around while he played and riffed on Mendelssohn’s violin concerto. Ooh, and peeking out from under that is a ticket from a gallery show I attended. If I dig down, it’s also full of objects: dog collars, a resin memento Gilliell made when Caine died, a thing I was making for someone else who died, first (note to self: work faster, sometimes!)

Those memory objects would mean nothing to you or anyone else and most of the other people who helped create those memories have moved on, died, or forgotten them themselves. If you were to go through it, you’d think it was a drawer full of junk, which is, perhaps, the point.

One of my projects in the next couple years is to build a wooden chest for the memories, instead of just jamming them into the drawer – some kind of wood that will burn easily. Because there is a codicil in my will that it’ll all go on a bonfire when I’m out of the Marcus business. That’s not because my memory drawer is like Jeffrey Epstein’s, it’s just that I don’t want to put anyone else in the position of having to decide what to do with any of it. By the way, you should also think about having a codicil in your will for the disposal or preservation of your data. I’m a data packrat; I have every email I’ve sent or received since 1984, and tons of digital photos and video clips. Some of that stuff has been interesting in various patent litigations, but by the time I’m gone, I think it’s OK to have all of that go, as well. The executor of my estate has a directive to destroy all hard drives in my office; I keep thinking about encrypting them (so the key goes with me!) but if the whole idea of this exercise is “what if I start to forget?” that might be a bad strategy. The point, again, is that these things mean stuff to me and when I’m gone they ought not to mean a whole lot to anyone else.

My memories touch other people, of course – but I feel that it’s their problem to remember what they want to remember, in their own way. I had an experience with that, once, where I sat down with my first true-love and we looked at some of our old letters. Because I have those, of course. We stopped pretty quickly because we’re cynical and worldly, now, and the thoughts of those callow youth have become alien to us. It made me wonder what then-Marcus would say if I could have come back through a time-machine and said, “Hey, that nuclear war you worry about all the time? We’re going to strangle in carbon dioxide, instead. Enjoy the day.”

That’s what I’d like to encourage you to do: remember the things that shape you; keep fragments somewhere where you can tangibly rummage through them, just like you rummage through them metaphorically. It doesn’t have to be a nice box, or a fancy drawer – but I guarantee you there’ll be stuff that you’ll miss when it’s gone. There’s an art, in fact, to coming up with things that will symbolize an event to you – for example, that USENIX conference badge from the early 90s: that was my first conference presentation. I could have included the viewgraphs from my powerpoint deck but the badge works just as well. Think about it: you’re compressing yourself.

My memory drawer only goes back 15 years. I didn’t have the idea until much later than I should have. It happened when my aunt, my favorite little old lady, went to the hospital for a minor procedure and never came back. My cousin, distraught, called me up and said, “What do I do with all this stuff?! The house is full of half-finished projects and things I don’t even understand. What do I do with this?” That was when I reached down into some profound well of bullshit and said “The meaning of those things died with her. I suggest you pick one or two things from the house that are meaningful to you and call an estate agent to get rid of the rest. It’s not disrespectful; it’s what happens to everyone.” That evening, after we talked, I thought hard about existentialism and gained a new appreciation for Camus. The first thing that went in the memory drawer is the length of black ribbon I used to tie my hair back at the funeral. Not all memories are happy, but that one serves as a stand-in for the whole arc of my time knowing her. Besides, none of it matters to anyone but the two of us anymore, and she’s done caring.

I’d like to end this on an upbeat note but I don’t think that’s possible when what I’m talking about is our reaction in the face of loss and meaninglessness. If you’re a cynic like me, who takes a dark view of everything, every happiness is tinged with the black velvet lining of eventual loss. When I confront that, I remember that none of it matters: when we’re gone we exist briefly as a ghost in other people’s memories and eventually we fray, wisp, and blow away. If you were a great person, that’s how it will happen. If you were a piece of shit, that will happen, too. In either case, you’re a custodian of your memories – so don’t lose them, and don’t forget to spare a thought now and then and wonder if other people’s memories of you will be sweet, nurturing, provocative, interesting, or whatever. That’s what the existentialsts got right. The nihilists appear to me to be right, that there’s no meaning and it’s all a sort of cosmic joke – but that doesn’t mean that we can’t take the joke seriously when it applies to our personal memories.

Thanks for being here.

Beautifully and wonderfully said.

So… both good and bad memories, or only the former?

Thanks for your blog.

I consider myself a hedonist. Enjoyment is what constitutes meaning in my life. As long as I’m happy, I can keep on living. Once my life becomes too painful/shitty with nothing to look forward to, then I’ll have to kill myself. Hopefully that won’t happen before my body starts falling apart due to old age. Of course, there are some other things that I care about (for example, art), but overall enjoyment is the most important thing for me.

Died, sure, but I wouldn’t be so certain about “moved on” and “forgotten.” If you shared some enjoyable experience with another person, the chances are that they also cherish this memory.

Please tell me that the hard drives with your digital photography are exempt from this. I really love your artistic nude photos, the thought of them getting destroyed would make me very sad. I hate it when artworks get destroyed after the artist who made them dies. It’s always sad per se. And since I like your photos so much, your digital photos getting destroyed would seem sad for me. (In case you don’t have anyone who would want to take care of your digital photo hard drives, I can volunteer. I’d love to get my hands on a hard drive with your photos. Of course, I would agree not to do with your photos anything that’s not acceptable for you.)

Have you read Neil Gaiman’s Signal to Noise? If not, I think you’d like it.

That’s reminiscent of the zen koan, “What are you doing?”

Until I transitioned five years ago, I didn’t live, I existed. I used “things” to replace the emptiness. I came to realize of all that junk I only valued one thing: a photo of myself and friends from college. It’s still only my friends and relationships that matter to me.

It’s only as I passed 50 that I “got it”: the only things that of consequence I have or will leave behind are their memories of me. I wish I had learnt this sooner, but better late than never.

“That is all very well, but now we must tend our garden.”

John Morales@#2:

So… both good and bad memories, or only the former?

Some are a mix and some are outright bad. There is one blood-soaked rag that reminds me to be more careful of certain things.

Aren’t some memories warnings?

Dunc@#4:

Have you read Neil Gaiman’s Signal to Noise? If not, I think you’d like it.

Thanks for the suggestion; I just ordered a copy. I haven’t been keeping up with his output and it’s good to remedy that.

Intransitive@#5:

That’s reminiscent of the zen koan, “What are you doing?”

I think that if we do something constantly it reinforces the memory, so it’s not necessary to rehearse it mentally until one stops. That’s a cool koan; I’ve heard variations on it before, I think.

I came to realize of all that junk I only valued one thing: a photo of myself and friends from college. It’s still only my friends and relationships that matter to me.

Epicurus would say something about that being the only true wealth. Ah, yes:

“That is all very well, but now we must tend our garden.”

Have you seen the theatrical version of Candide? It’s not bad.

Andreas Avester@#3:

Died, sure, but I wouldn’t be so certain about “moved on” and “forgotten.” If you shared some enjoyable experience with another person, the chances are that they also cherish this memory.

That’s true. Or their memory can be completely different. My approach to other people’s memories encompasses that possibility. For example, I had the experience once of remembering one day as having been really good but the person who spent it with me later told me it was tedious and she was thinking the whole time how much they wished I’d choke on my food. That was a bit extreme (and I’m not sure I believe it) but we do remember things differently and often significantly so.

Please tell me that the hard drives with your digital photography are exempt from this. I really love your artistic nude photos, the thought of them getting destroyed would make me very sad.

Well, here’s the thing. I’ve published all the images I want to publish as finished artworks; I don’t want to or intend to publish the raw versions. So what will be lost is the high resolution versions, which I never plan to publish anyway. And, for my out-takes, I scrub through those (or used to) and post the ones that are good but not good enough to publish as finished artworks in my stock collection. The way I see it, I’ve published the stuff that I want to publish, and the other stuff is never going to see the light of day, anyhow. It also saves me having to scrub through an image archive that has a huge number of images, deleting any that are particularly awkward. I have one photo of a model slipping and falling on their ass – they would be happy to know that image goes into the bitbucket when I do.

My agreements with all of my friends include both of us being able to openly give the other person feedback about what we like. When I’m hanging out with a friend, each of us can suggest changing the conversation topic or the activity we are doing at any moment if we get bored. This is something I always explicitly discuss with my friends so that we both can agree about it. I’m pretty certain that this arrangement works for me and the few close friends I have, because I have been told often enough that something that excites me seems boring for one of my friends. I do trust my friends to give me honest feedback. Moreover, if I couldn’t trust some person not to get offended by me not sharing one of their interests, then that’s no friendship anyway.

I try to extend this attitude also when hanging with people I don’t know so well. For example, in Germany I told you to let me know if at any point I annoyed or bored you. Of course, I have no way of knowing whether some acquaintance actually chose to follow my request or no, but at least I’m trying my best with attempting to establish honest communication. As for me, unless I’m at work and I need to be polite towards a boss or a client, I won’t be pretending to enjoy some activity that’s actually boring for me. Whenever I don’t like something, I just say so. It’s not my job to pretend in order to please other people.

I find this very sad. The way how digital photography works, a photographer will take at least several dozen (if not several hundred) photos in a single shooting session. We will publish only one, maybe a couple. Many of the non-published photos are likely to be just as good as the single photo that actually got published. I don’t even need to make this argument, because you wrote about that here— https://www.deviantart.com/mjranum/journal/An-Embarrassment-of-Riches-238902942

I just hate it so much when artists destroy their works which for whatever reason didn’t end up published.

I dislike it when people waste things in general. It saddens me to watch people throw out perfectly edible food in a world where others would like to eat it. In the city where I live there are lots of houses that stay empty. It’s more convenient for the owners to just leave the houses empty and wait for them to fall apart rather than sell or rent these homes. Simultaneously, there are lots of people who need housing. I dislike such wastefulness. If you own something that you don’t need in a world where other people would love to use it, then keeping said stuff to yourself is wasteful. I’d argue it’s wrong. A dead artist no longer needs their art archive. Thus it would be better to just publish it all rather than destroy it.

When the thing that goes to waste is food or a house, then it’s a generic thing. That apple you threw in the garbage bin only because you didn’t want to eat it wasn’t unique—humanity can produce many other apples that will be the same. This is true also for most houses, which are also generic (except for the few ones that are truly beautiful architectural artworks). But artworks aren’t generic. They are unique. This is why, in my opinion, whenever an artist destroys their own work, it’s the worst form of wastefulness imaginable. They destroy something unique, something that cannot be recreated. And they destroy artworks merely because they no longer need them, and giving everything away to the public would be extra work.

Of course, you own your photos and you also have the right to destroy them after your death. But the fact that you have chosen to do so makes me extremely sad. (Please don’t do that, I’m begging you.)

By the way, personally I’m not publishing full resolution digital photos and scanned artworks online, because I am alive and I still need my art as a source of income. Nor am I publishing every single good photo that I have ever made, because this would make the overall appearance of my portfolio worse. I’m still alive, I’m a working artist, and I need a good-looking portfolio to make money with my art. But none of this will matter for me once I’m dead. This is why I’m building a collection of all my full resolution digital photos and artwork scans. For now this stuff sits on my hard drive, but I’m planning to dump it all online upon retiring. If other people will decide that they value my digital art, then they will preserve copies of it. If they collectively decide that nobody wants to preserve it and pay for the storage, that’s fine. I’ll be dead, and I won’t care. If the society doesn’t value some artwork and doesn’t want to preserve it, that’s fine. If nobody needs some artwork, it will just get destroyed as time goes by. But I believe that I have no right to destroy my own artworks, it would be wrong for me to deprive the society of my art. In case there’s at least one person who likes my art and wants to preserve it for their own enjoyment after my death, then I should make it possible for them to do so. In case there’s nobody who wants to preserve my art after my death, oh well, whatever. I won’t care anyway. But at least I won’t be the one who decides to destroy my art.

By the way, in case you imagined that there’s nobody who would be interested in preserving your art, that’s wrong—there’s me, so that makes at least one person. Besides, I know that there were also plenty of other people who like your photos.

The way I see it, what happens with my art after my death isn’t about me. It’s not about whether I wanted to publish some particular image. It’s not about what is more convenient for me (sure, I know that scrubbing through an image archive and deleting the awkward ones is extra work). I will be dead. I won’t care. I won’t need my art anymore. This isn’t about what I need or want, instead this is about other people. As long as there’s at least one person who would like to preserve my digital art after my death for their own enjoyment, I should provide them the opportunity to do so. The way I see it, whenever I no longer need something (and dead people don’t need anything at all), I should give this thing away for others who might like to have my stuff.

By the way, I am a person who has done dumpster diving. It annoys me when people throw out a bag of potatoes that I would have liked to appropriate for my own consumption. If people have stuff they no longer need or want, instead of depositing it at the bottom of a dumpster where I cannot reach it, they should just place it somewhere more accessible so that I can get my hands on it (I’m not athletic enough to jump into most garbage containers). I’m too lazy to get a real job, so this is how I have chosen to live, I take whatever still usable stuff others no longer need, because this way I don’t have to buy almost anything and I can can work for less than 16 hours per week. I get sad or annoyed even about trivial stuff getting wasted, and art being destroyed is just so many magnitudes worse.

Beautiful post and idea, mjr. I am going to start one. I need a good box.

I reckon what the nihilists have done here is point out, while committing, a category error.

“Meaning” is a sapient’s thing. For anything to have meaning it must be interpreted, which is the action of a mind. The universe at large, being (as best we can tell) not sapient, has no meaning because the concept doesn’t apply.

So the nihilists are right that there is no meaning inherent in the universe – but committing the same category error by concluding that there can’t be that meaning must be inherent to be, well, meaningful.

We have to create our own meaning. Where else could it come from, since we are the sapients available to do the interpreting. People who go looking for meaning either find religion (meaning made up by sapients and then falsely ATTRIBUTED to the universe), or realize the only way to have meaning in one’s life is to choose to create it.

* there

can’t be thatmeaning must be inherentabbeycadabra @#12

Finding meaning in religion always seemed odd for me. Basically, God made you as his servant, a tiny screw in his system, nothing but his tool. That sounds like a really meaningless existence to me. If the purpose of my life were to serve somebody else, I would quickly start to feel really suicidal. Why should I serve some cosmic overlord? What’s in it for me? I just don’t want to serve anybody. Every now and then I also hear some people (often nationalists) talking about how each person must devote their own life to serving the needs of the society (in less oppressive countries) or the dear leader (in more totalitarian countries). This idea also seems odd for me. I just don’t like the idea of devoting my life to some authority. I hate being given orders.

Andreas,

The Abrahamic god-construct is the tiniest sliver of religion, and thus you have indulged in a hasty generalisation.

—

abbeycadabra:

If you’re referring to existential meaning, then no. Like existential purpose, that’s only necessary if you need meaning or purpose. Not all of us do.

abbeycadabra@#12:

For anything to have meaning it must be interpreted, which is the action of a mind. The universe at large, being (as best we can tell) not sapient, has no meaning because the concept doesn’t apply.

Fair enough. I was not being rigorous. First off, the extreme skeptic/nihilist wouldn’t assert “the universe has no meaning” because that’s also a dogmatic claim; they’d just say that they’re unconvinced by the claims that they have heard. That would place the burden of defining “meaning” on the person claiming that it does have meaning (as you say: category error).

I do agree with you in that my understanding of “meaning” entails “meaning to me” which reinforces the idea that it’s hard to say anything has meaning, not least of which would be the universe. The argument that meaning is a personal experience in a sapient is a fairly existentialist position, which I mostly agree with as far as it goes. The problem with it is that it’s basically “the meaning of no meaning” – saying that something gets its meaning because I assign it meaning is a pretty good shorthand for “it’s meaningless” – my opinion means nothing and I may as well just reject the idea that “meaning” has any meaning that I can discern. [I don’t have much respect for existentialist notions of meaning; they appear to me to be just ways of reifying one’s opinion as being more important than it seems to be.]

[utterly OT, but, topic drift]

https://www.abc.net.au/religion/susan-neiman-why-reason-needs-reverence-moral-clarity-from-the/11505232

A perfect example of religious thinking, by someone who is otherwise a rather impressive thinker, as demonstrated by this essay. Religious, but free-thinking.

At least Susan makes it clear it’s all abstractions.

(So yeah, even really smart people well-versed in reasoning go that route)

John Morales @#15

Christians and Muslims combined make more than 50% of the world’s population. That’s not “tiniest sliver.” And those are the global numbers. In Europe and the USA Abrahamic religions are much more predominant than in the world in general. Where I live, when some believer tells me to seek meaning in religion, they are thinking about the Christian God, they aren’t suggesting me to study Buddhism.

Caterogy error, Andreas.

It’s not about how many adherents that sliver has, it’s about the taxonomic scope of religion.

But sure, evangelistic authoritarian religions are particularly pernicious.

(Somewhat analogically, by far most of the matter in this universe is hydrogen, but generally when I speak of matter I don’t specifically refer to hydrogen)