Once upon a time, there were two demons talking. One of them looked at the other and said, “whoah, you’ve got the ‘made the damned suffer’ award, how did you earn that?” The other demon replied, “I made the integral bolster knife popular, and the overall suffering in the knife-maker community went off the charts.”

The problem with an integral bolster is that the metal must be graceful and properly finished (that’s a given) but As you are shaping the metal, you’ve got to make the bolster perfectly flat so it mates with the handle, which is not easy to do because there’s a tang sticking out of the middle of the darned thing. Some knife-makers spend a great deal of time making it machinist-flat the hard way, with filing guides (or a vise) and time and lots of filing.

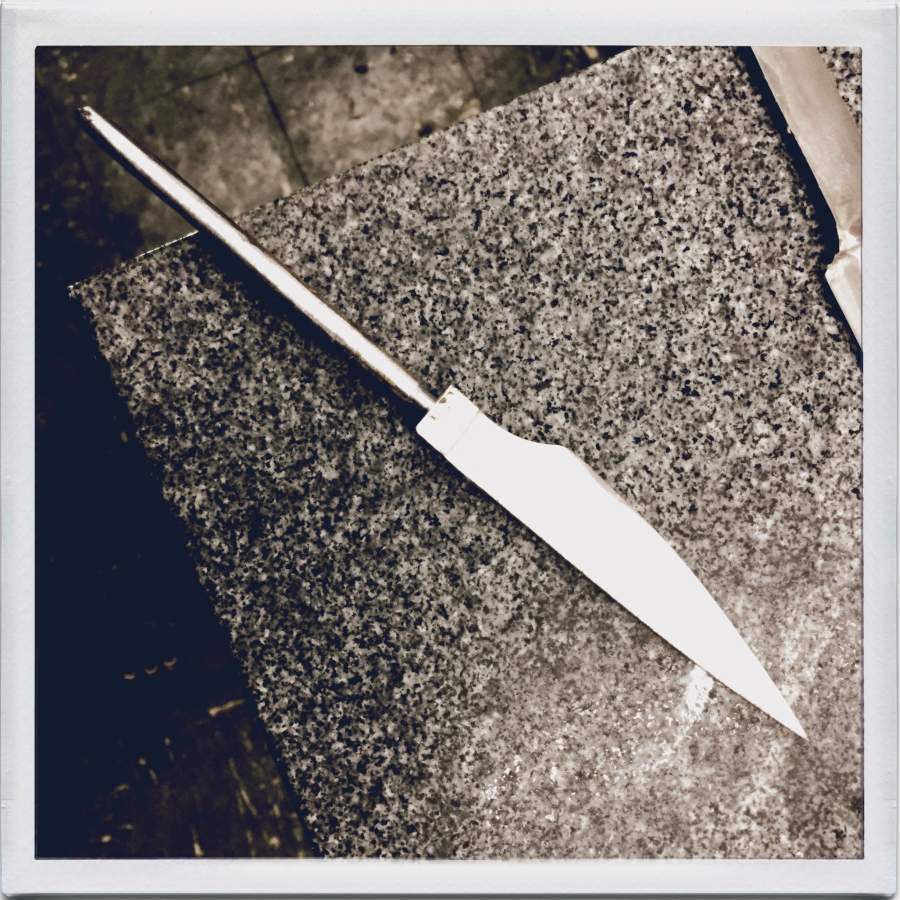

Jazzlet made a comment the other day about a short paring knife being a cool thing, and I had a gooby of twisted 15n20 and 1095 sitting on the shelf, so I decided to try a sort of paring knife-oid, and – as I began whacking away to shape the tang, I noticed that I had enough metal left in the middle for an integral bolster. “Great! I’ll try it!”

When I started profiling the blade, I began to understand the curse of the integral bolster. There was just no way that was going to come out straight and flat without me pulling my hair out. But, wait! I had been noodling around, making the tang very round – because I could – and I decided, “What the heck! That looks like what lathes are for!” I have a small benchtop metal lathe and it was a matter of a couple minutes to plug it in, check it over, and chuck up the tang.

I positioned a flat/square ended cutter near the tang, fired up the lathe, then shaved the tang down a bit and slowly walked the cutter over into the top of the bolster. Incredible! In seconds I had a perfectly flat bolster-face. Now, I just have to not screw it up.

I think that, often, professional knife-makers produce options that are deliberately difficult, to separate them from the masses. That’s fine, of course, but it results in a thing I personally find a bit unattractive: difficulty for its own sake. If you have a CNC surface grinder, you can a) avoid spending all the time grinding your bars perfectly flat b) never have a bad weld because your bars are perfectly flat – and that allows you to do complicated multi-bar assemblies reliably. An amateur with normal gear might have 1 in 10 or even 1 in 5 bars turn out a failure, but if you have the right tools, you can save a huge amount of time and get better looking results.

If it comes out OK, it’ll definitely be something that’ll put an eye out. If you’re a potato.

I will be doing a charity auction for the chef’s pwning knife, which is not a perfect specimen, but is a pretty good usable knife. The money will go to the FTB legal defense fund. I’m not sure how I’ll run the auction, yet – probably I’ll take bids for a certain time in the comment section or by email (in case someone wishes to conceal the fact that they are bidding) – if I get a bid by email I’ll just enter it in a comment as “email bid”. Since the bidding will be manual, I will not be able to support people bid-sniping at the last minute if they’re emailing bids in. Perhaps nobody will bid, anyway.

A number of years ago I started an experiment to see what my wet plate ambrotypes were “worth” by listing them on Ebay with a starting bid of $1. I was impressed to see that they started out fetching a few dollars but I quickly gained a small following and some of the plates fetched a few hundred dollars. So, I concluded I knew what my photos were worth. Managing the auctions and packaging the work was a huge pain in the butt, so I eventually stopped. What killed it for me was that I sometimes turned the plates into shadow-boxed assemblies, which (naturally) took much more time in addition to just shooting the photograph and finishing and varnishing the plate. The free market told me something: the bare plates were worth more than my more elaborate art-works. Ow! Rejection! I did one last shadow-box, which was one by a fellow who was actually a collector of my stuff and when I shipped it to him, the postal service managed to utterly crush the box and its packaging, and the solid oak box-frame around the plate. They must have parked a car on it, or something. The plate was cracked, too. So I decided to do something unusual and I got the model to come back and re-shot the plate, then re-made the box, then shipped it insured, fedex, in a big box with loads of padding. It made it. I should have just refunded the money but I was so chuffed that someone liked my stuff, that I made sure that he ended up with it.

Must feel nice to know you are helping some demons earn awards. :)

That’s really beautiful! Nice job. The finished product will be gorgeous!

As someone who does some difficult techniques (in my case, in horsehair braiding), I can say that deliberately doing something difficult is not necessarily just to make it harder, in my case anyway it’s because *I know how to do it* and it sets my work apart from everyone else’s. It is not difficult for me; I have enough years of experience and practice that for me it’s a piece of cake. My opinion is that those braids are more beautiful and I prefer them, so I was willing to put in the effort to learn them. Maybe after doing some of these they won’t seem difficult to you; they’ll just seem like “the right way to do it”.

An auction! That’s a great idea!