Dawn Sturgess died over the weekend. She appears to have been killed with novichok – the specialized Russian chemical warfare agent – so far, police aren’t saying anything about how she could have come into contact with it. [nyt] This is the same chemical agent that was used to nearly kill Sergei and Yulia Skripal.

Dawn Sturgess, early casualty in Cold War 2.0

After WWI there was interest in restricting the use of chemical weapons. We’ve all heard about that. We’ve also (most of us) heard the US getting up on its high horse about “red lines” regarding chemical warfare – while it’s OK to use high explosive or white phosphorus or depleted uranium on people, it’s not OK to use other chemical agents. That got me to thinking “why is it acceptable that Russia is making things like novichok, and the US is complaining about its use but not that it exists at all?” It seems like one of those situations where the world’s top military powers are concerned with making sure that they have certain weapons that nobody else has.

Oh boy, right again.

If you start wading into the regulatory frameworks around these things, they will make your head hurt. Because, when you come right down to it, chemical weapons are pretty easy to make – they’re just not top-quality professional-grade weapons like novichok. But, if you dump a load of hydroflouric acid on a town, you’re going to do some horrible nasty damage and ruin people’s lives – which is the point of the exercise. As we can tell from the novichok attack in England, these weapons can be used with a specific target, but even then, their effects can spread accidentally. The cost of the novichok attack is going to be huge; how do you get rid of the stuff when you don’t even know where it’s been tracked?

It would seem, to the mythical rational person, that rules against chemical weapons ought to fall directly out of rules against torturing people, genocide, and harming civilians. In other words, since the novichok attack was, presumably, launched by Russia (more precisely: Russians acting on behalf of Russia) against civilians, it’s a crime against humanity. Of course, it cannot be treated as such because then the international criminal court would have to rule on napalming civilians, or using white phosporus against civilian targets. It ought to be obvious.

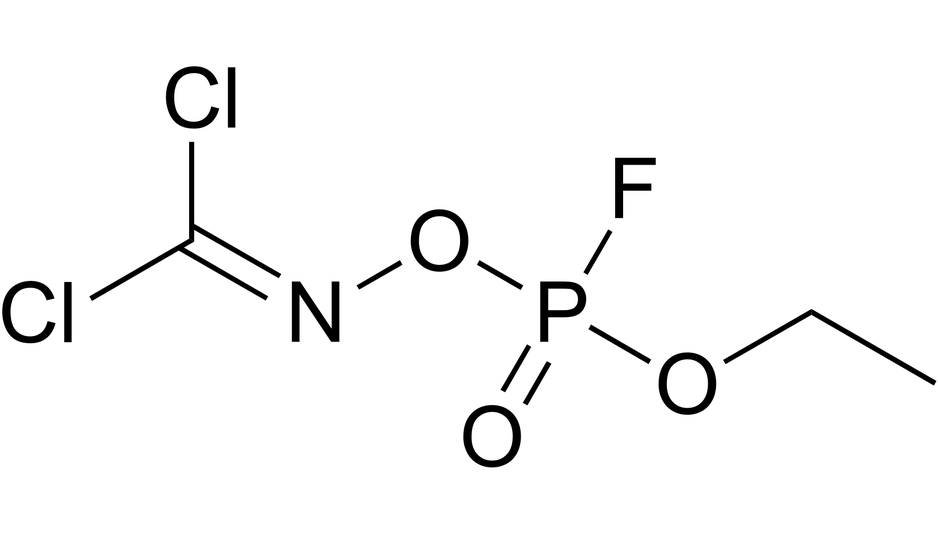

just another acetycholinesterase inhibitor

But, when you start digging into the regulatory frameworks intended that the weak can regulate the strong, what you find everywhere is loopholes. Because, in the middle of a sort of deadly embrace, the US and Russia are agreeing that nobody else but them should use chemical weapons on people – while maintaining the public illusion otherwise that these weapons are bad. You’ve probably noticed by now that journalists haven’t been asking “why is is that Russia is researching things like novichok when the US is bombing Syrian chemical weapons research facilities?”

The answer is distressingly obvious: because Russia is not a doormat for the superior militaries of Europe and the US. Syria can be bombed with impunity – some chemical institute somewhere in Russia cannot. I assume that the US has similar facilities, as well. It would be unlike the US to tolerate a “novichok gap” and the speed with which the US and British governments were able to identify and categorize the weapon are telling: they already know what it is, and they probably have their own supply of the stuff.

Back to loopholes: if you were writing a convention on not using chemical weapons, how would you do it?

I imagine a beautifully crafted statement to the effect that “you do not use chemicals on people or groups of people to cause them harm.” The framing would be in line with international humanitarian law: “do not do this thing.” We do not need to say “do not drop acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on anyone” because that is too specific. The US government would immediately start characterizing it as a ban on air-dropped chemical weapons, and would start spraying them at ground level. The problem is that the powerful governments are going to do these horrible, evil, things and they’re going to figure out a way of doing them (or they’ll just lie and hide it) so attempts to regulate them really only apply to the Melians. Or Syrians. Or North Koreans.

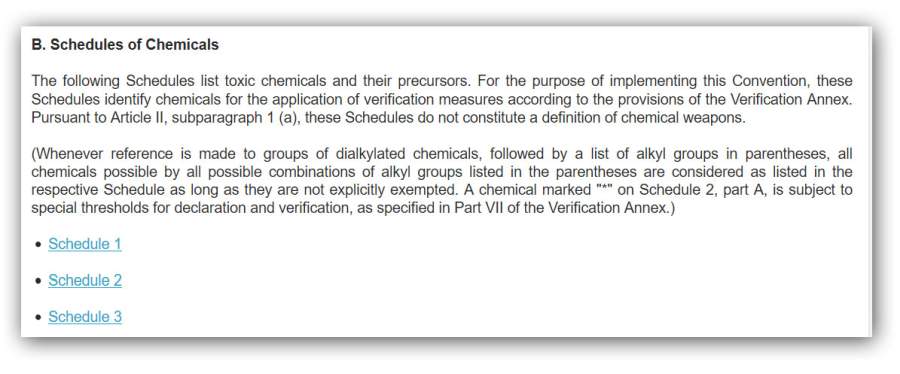

I’m not going to say that The Convention on Chemical Weapons [opcw] is clearly backdoored, but I’m suspicious. Rather than trying to regulate the behavior it regulates the chemistry. And that’s how you get things like novichok: it’s a clever new variant of organophosphate that isn’t on the list of chemical weapons. The other thing the convention regulates is precursors – so you’re not supposed to stockpile industrial quantities of the precursors for Sarin (and Sarin is on the list of “no-no” but novichok is not) That set-up’s going to make it a bit harder for a poor country that can only afford to make Sarin, but it leaves a vast field of organic chemistry open for the Russians (and presumably the US) It’s hard not to be cynical about this stuff, so I’m just going to be cynical, OK?

But wait, there’s more! Since the regulations govern known chemical weapons and precursors, it has to be restricted to precursors that have limited use, otherwise. What about hydroflouric acid? Well, HF has its uses – other than giving chem lab students nightmares – so they can’t regulate it as a precursor for a chemical weapon because it has legitimate use. And that’s why the Syrian government has been dumping chlorine on its citizens: it’s not a chemical weapon. It’s not on the list. It’s necessary for too many other purposes so it’s OK to stockpile it and since it’s not a “chemical weapon” the international community has to dance around and pretend that the Syrian government is just doing a perfectly reasonable thing for governments to do.

Wait ’till you hear the outcry about “why is Russia still developing innovative chemical warfare weapons?” It’s going to be a while.

I’m sympathetic to the regulators – they have an impossible problem – you can’t regulate chemistry. And you can’t regulate its use because the powerful states are going to just do what they want, anyway.

When I was in basic training we did a whole module on CBN (chemical, biological, nuclear) and it was horrible – they lied to us about what we might encounter, and they lied about the effectiveness of the countermeasures. That was sobering, indeed. It was also sobering when they gave us the push-injectors of atropine and showed how the needle came out, and the sergeant said, “it probably won’t work but it’s better than dying of a huge dose of insecticide. Did you notice how bugs don’t seem to like that?”

This is a very depressing topic for me: every time I look at “the international system” it appears that the US, China, and Russia (and Israel) have exempted themselves from it, except where they want to use it to bludgeon everyone else.

“the US is bombing Syrian chemical weapons research facilities?” – I am skeptical about that. My lab over at the shop is probably “a chemical weapons research facility” too (I have cyanide! and flourine! and concentrated nitric acid!) What does a chemical weapons lab really look like? The US or Russia could tell us, because they have them. This situation is exactly paralleled with Mohamed El Baradei’s pointing out that the Iraqi “nuclear research facility” was a partially collapsed building with some rotting documents that were largely open-publication books about nuclear weapons. My shelf on nuclear weapons in my library probably contains more secrets than the Iraqi “facility.”

It’s a common problem, for instance with “designer drugs”: Take something illegal, add a few methyl groups or other bits so that it still works and sell it. Until regulators / law enforcment catch up it’s a “legal high” provided you manage to avoid clashing with more general regulations, e.g. for pharmaceuticals.

There’s a flipside to this, too: Patent protection. A lecturer in chemistry once told us that if you want to patent for your latest wonder drug you have to provide all sorts of analytical data to show what it is you’re patenting. If you get the data wrong and someone else get’s wind of it you may end up with a worthless patent and a lot of R&D bills that go unpaid. Rifling through other people’s patents and intellectual property is apparently a Thing people do to make money. It’s not theft if someone botched their patent application. “It’s not illegal” is all the moral high ground some people need after all.

komarov@#1:

“It’s not illegal” is all the moral high ground some people need after all.

Related but unrelated: the FBI deploys face-recognition databases and collects millions of images. Only then is there some discussion about “is this legal?” Well, the fact that they didn’t ask first tells you that they think it probably is illegal, and were trying to present a fair accompli. If I were about to do something questionable, I’d ask my attorney first and, having asked, I’d follow their guidance (because if they said, “actually, that’s a felony” I am now on notice that my legal counsel informed me it was a felony.)

I am surprised the Russians used novichok instead of something with less of a signature. It’s like they’re sending a message by signing their work. “Ha, you mice can’t bell this cat!”

I think using Novichok is Putin saying ‘I can do whatever I want and you can’t touch me’. Which is pretty much true.

I’ve heard of a few cases where the legal advice was “that may or may not be legal. The only way to find out is if you do it, someone gets angry at you, and then we work it out”. Followed by a subtle hint to not ask next time because now the lawyer is aware of the issue and can’t plead ignorance.

The legal code is full of bugs :\

Re: #1 @komarov (and yes, this is kinda getting off-topic):

That “Thing” is one of the whole points of patent law: to get the ideas and techniques out into the open, both for free use when the patent has expired and for any other type of gain before it expires.

I’m sure that situations can arise where the sort of “unfairness” you describe is clearly happening, but it’s hardly the least unfair thing that happens in patent law. We could start with you being unable to use your own entirely independently developed technique because someone else had the same idea and and patented the technique first. A close second would be people like James Watt, who basically managed to stall steam engine development for almost a quarter decade (despite better models having been designed and built) through use of his patents. And then of course there are modern-day patent trolls.

It’s clearly an imperfect system, but remember: the government doesn’t grant IP monopolies because there’s some sort of natural law about “theft” that applies to some ideas but not others, the way you an argue there is about physical property. It does so (at least in theory) because of the essentially socialist, anti-free-market idea that if, as a form of payment to inventors, we grant government-mandated monopolies on things that could otherwise be freely used, the people as a whole will benefit. (That’s also why there are modern restrictions on what can be patented; you can no longer have a patent on the colour purple, for example.) The alternative, not making such an offer, would incentivise people to keep their ideas as secret as possible and the theory is that these ideas would be then be lost.

Boldrin and Levine’s Against Intellectual Monopoly is a good antidote to the woo surrounding intellectual property. They may go too far (or not far enough) depending on your opinion, but at least they do a good job of bringing to the fore what this is really about, and it’s nothing to do with any kind of natural or moral rights.

It’s all a hoax:

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2018-07-07/no-nerve-agents-douma-opcw-report-demolishes-white-house-sarin-narrative

Marcus:

hydrofluoric (2x)

Nasty stuff indeed.

I am surprised the Russians used novichok instead of something with less of a signature.

Which is one of several reasons I really don’t believe the Russian Gov’t had anything to do with the attack on the Skripals. It would have been easier to shove Sergai Skripal in Salisbury.

Theresa May’s screaming that it was the Russians was based on nothing and the case has gotten weaker ever since. May needed any distraction she could find to divert some attention away from the goon show of the Brexit negotiations.

That should be “shove under a bus”.

Jazzlet @3:

Exactly. It’s not meant to be a secret or a perfect unsolvable murder. The purpose of using these methods is clearly to intimidate. To instill fear in potential targets, like any colleagues of Mr. Skripal, that they’re not safe anywhere and that the Russian state will go to any length and expend any cost to get back at its opponents and detractors. As long as it can’t be conclusively proven (“beyond reasonable doubt”) that the Russian government is responsible Putin is quite happy to have everyone at least believe they’re responsible. That’s why they’re doing this, it’s a form of PR.

Anyone who doesn’t believe the Russian government is responsible because it would be too obvious is missing the point. It needs to be obvious – but deniable – to work.

Have you seen what happened to the last few ones that betrayed us? We didn’t do it but it would be a shame if it also happened to you. Or your daughter. Capisce?