I feel like we typically leave big parts of our lives and motivations unexamined; sometimes, if we’re lucky, something happens that makes us engage our brains about one thing or another and we examine it and think about it enough to get an idea about how we work inside.

In 2006 or so, a photographer friend asked me to substitute teach a class he was scheduled for: “erotic photography” – naturally I said yes, and then I realized I had stepped into a totally new sort of mess. You’re probably familiar with the idea “the way to really test your knowledge of ${thing} is to teach” – and it’s true, as far as it goes. By 2006 I had hundreds of hours of teaching experience already, so I understood my process:

- think “How did I learn ${thing}? What were the critical concepts and waypoints?”

- what things later made me slap myself on the forehead and go “I wish I had learned that first?”

- build an ordering of presentation of concepts

- figure out how to explain them

- intersperse the concepts with practical things that the students can do that will help them understand not just the material but their own relationship to the material

Madame Recamier, by Chinard

But setting up an internet firewall or a vulnerability management program contains certain elements that are close to objective truths: do this, don’t do that, or you will get hacked. “Erotic photography”? Did you not notice, Marcus, that “erotic” is personal and dependent on experience and exposure and cultural norms? Why did you say “sure”? Then I realized my path of attack had to follow my own process of discovery: the best I could hope for was to encourage the class to think about the problem of “what is erotic” because only once you have some ideas about that can you go photograph them.

So I sat and drank some wine and thought about “how do you think about what is erotic?” The whole experience was very worthwhile, I felt, and eventually I came up with a couple of methods for exploring my own reactions. For the class, I was allowed to assign the attendees to bring things or whatever (within reason) so I asked attendees to “email me or bring 2 or 3 pictures that you feel are erotic” – that was how I was going to break into that discussion.

shoe by Helmut Newton – or is this a photo of a foot?

The idea is that there may be certain things in an individual that they really like, and we might be able to pick out commonalities. There might even be certain things that most of us tended to like, and we could search for those commonalities, too. Once a person understands a bit better, “I tend to like ${whatever}” then they can orient their art accordingly. There’s a corollary to that, which is if you’re seeking commercial success you use a similar process and deconstruct what is commercially successful and accept that maybe what you like doesn’t matter so much. Of course great artists don’t follow a deconstructive process so they can produce a bunch of “crowd pleasers” – they find something we like that we didn’t know we liked; they see those commonalities or they share them themselves and they reach out and we experience a shock of recognition. How did Jimi Hendrix know that his lead into “Voodoo Child” would melt my mind? Because he was trying to melt his own mind and, being a master of his instrument, he used his understanding of himself to appeal to my non-understanding self.

The class went pretty well, by the way. I learned a lot – for one thing we concluded that most of us seemed to like our “erotic” images with higher contrast so that the composition was emphasized. There was a split regarding humor – half of us liked our erotica to engage us cognitively (“that’s funny/odd!”) which I interpreted as a search for narrative meaning; does the picture tell a story that arouses us because it is familiar or engaging or curious? One of the people in the workshop brought several photos (including one of my favorites by Jeanloup Sieff) – and his were all, well, emphatically about women’s backsides. He already knew what turned him on.

Collectively we realized, I think, how profoundly different our experience of eroticism is: it was simultaneously deeply personal as well as having some things in common. That was the purpose of the exercise but I felt that I learned more from it than everyone else because I had to spend more time carefully studying my own reactions.

And now we come to the point of this story, which is that before I did the class, I spent hours going through my own work, deconstructing my own preferences and reactions and searching for commonalities. So I noted that my preferences are generally pretty broad but there are certain trend-lines that run through them. One thing I noticed is that I have a strong preference for noses that show the structural cartilage that shapes them. My initial reaction to that was an emotional “what the fuck?!” but I realized that this was a bit of self-discovery I probably did not have to share with others, so I could think honestly about it and nobody’d accuse me of being a nasal cartilagist.

Note: there are people like Chuck Tingle who appear to be able to eroticize things that are a bit outside of my experience, but I noticed that Tingle appears to eroticize certain actions (“slammed in the butt by ${whatever} by Chuck Tingle”) I’m pretty pedestrian, apparently, but I have my ideas of beauty mixed up in my ideas of eroticism in a way I didn’t try to disentangle. There is a side-discussion we could have about what this shows us about the degree to which our sexuality is a learned behavior versus a programmed instinct. I started to realize that fetishism teaches us how wrong a lot of evolutionary psychology is: there were no latex cat-suits or Louboutin shoes to fetishize until relatively recently so it must be a learned behavior.

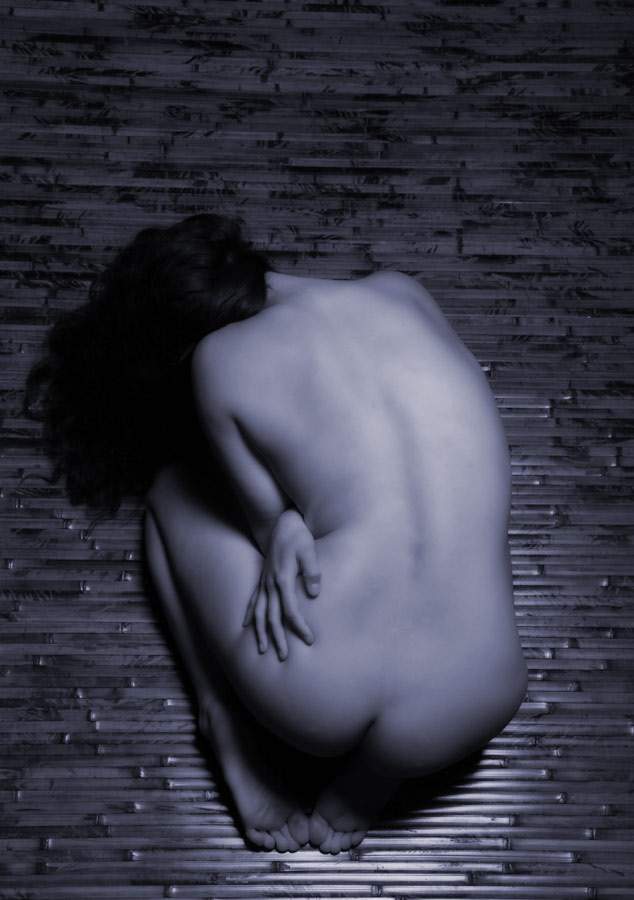

Freya, by mjr, 2010

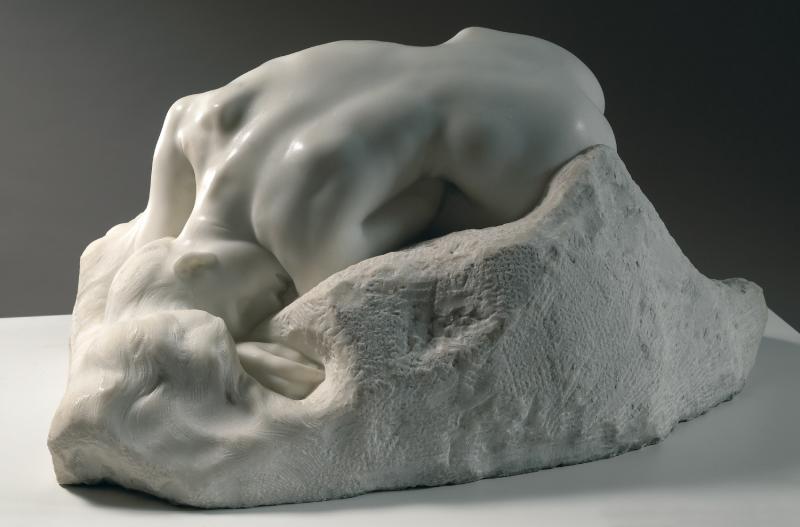

The obvious next step was to try to figure out “why?” I suppose it’s possible that my particular fondness for a facial feature might be genetically determined, but I decided to have a few glasses of wine and think really hard about it. There are more features than just the nose that I particularly like; it seemed like a matter of deconstructing the whole thing and seeing what I could figure out. So, there were really two things: why do I like certain faces? And why do I like certain bodies in certain poses? [refer back to my oblique comment about “what I like” on an earlier posting] so, after lots of hard thinking I remembered a couple things from my distant past – one was a bust of Madame Recamier that was in the hall of my parents’ house. The other is Rodin’s Dryad. Well, it just so happens that I believe Madame Recamier strongly helped create my beauty ideal, only – you know – in plaster form. And the Rodin: I do distinctly recall that I first felt the stirrings of my awakening interest in sex, on a certain day, in a certain place, and I was closely examining that particular sculpture.

I’ve heard the term “flashbulb memories” – the moments we feel we remember with an illuminated clarity that become nodes on the time-line of our self: watching the Challenger explode live, the big peace march in New York, my first kiss, 9/11. Well, Rodin’s sculpture is one of those for me and I’ve had a suspicious fondness for women’s hips in that pose ever since. And, if I am honest with myself 80% of the time if I see someone I think is strikingly pretty, they look more like Madame Recamier than not. Of course I could be making the same kind of error as Evolutionary Psychology, putting the effect ahead of the cause, but I really think it was Recamier. Contra Freud, who’d say “it’s your mother, fool!” my mom does not resemble Madame Recamier, at all. It’s all anecdote, I know, but my assessment of my self puts me strongly in the “nurture” camp. It might not be Madame Recamier whose features influenced me so much, it might be some other forgotten person or sculpture – who also looked like Madame Recamier.

I got so interested in this that I started asking my parents questions like, “when I was a kid, do you remember anything striking about such-and-such?” And sometimes I’d get back answers like “that used to be one of your favorite places until that time you got food poisoning from the sandwich you ate that day – come to think of it you never went back.” It can be humbling to realize the degree to which we are strongly formed by positive or negative impressions, even if they were never “real” – I’m sure Madame Recamier would have never given me the time of day (not having a smartphone like I do!) but I had a life-long crush on her thanks to a clay likeness.

Auguste Rodin, Danaide

Thus concludes my self-examination, attempting to dig back and see what it is I like about certain things that I like. I’ve done similar exercises with other things – for example my general dislike of mold-cured cheeses goes back to a childhood visit to the cheese caves in Roquefort, and the horrible smell. I feel as though any time I honestly deconstruct one of my attitudes, it maps back to something that happened in my formative years – it’s why they call them “formative years” after all. It seems funny to me how much we incorporate our learned experiences, then reify them as popular attitudes, when really they seem to be part of the great mixing-bowl of life.

Have any of you had similar experiences?

That’s a variation of another teaching technique I learned from a photographer named Tal Mcbride: you look at a photo that you like, then deconstruct the lighting in it – use clues like specularity, shadow angle, reflections – and try to understand how it was done as a way of getting at what it is you like about it.

My car’s alternator died during a road-trip, leaving me stranded for 12 hours in Tyrone, Pa. This post was written on my iPhone, so a higher level of typos and formatting errors should be expected.

I read somewhere (no idea where, that was long ago) that people learn a lot of their future behaviors by the time they are three years old. I have no idea if that is true or not.

Long before I can remember things, my parents told me that if I ever got hurt, I should not scream or cry but instead find an adult and ask for help. This is actually a bad strategy even though it sounds good. In the first grade, as an 8-year-old, my collar bone got broken during morning recess. I asked for help but the teachers all assumed there was actually nothing wrong with me since I was not crying. (If they had looked, they would surely have noticed the bone actually sticking out of the skin, but none of them looked.) They did not contact my parents or let me go home but insisted I stay in school, and when school was out I walked home, very very slowly. At home my mother took one look and whisked me to the doctor’s office. The nurses at the clinic took one look and next thing you know I was in seeing the doctor; I have never since gotten in to see a doctor so quickly. Later in life I asked my parents about this odd reaction of mine, the not crying thing, and they told me they had said this to me when I was very young. To this day physical pain does not make me cry or scream… lots of other things do, just not physical pain. Little children trust adults to a really scary degree.

kestrel@#1:

I read somewhere (no idea where, that was long ago) that people learn a lot of their future behaviors by the time they are three years old. I have no idea if that is true or not.

I’m skeptical; there was a lot of pretty dodgy research on infant learning in the 70s (mostly motivated by Piaget) – I have not kept up on the literature, though. But imagine how hard it would be to test for something like that.

Long before I can remember things, my parents told me that if I ever got hurt, I should not scream or cry but instead find an adult and ask for help. This is actually a bad strategy even though it sounds good. In the first grade, as an 8-year-old, my collar bone got broken during morning recess.

I winced so hard when I read that, I nearly did a back-flip in my chair.

My grandparents raised my dad during the depression, on basically nothing. So they taught him to always clean his plate. He taught me the same thing. I’m not saying it’s a bad algorithm, but in American restaurants with huge portion sizes, it has something to do with my waistline. But if I try to leave food behind, it’s almost physically painful.

One of the things motivating this posting is my feeling that evolutionary psychologists ignore the tremendous amount of experience that most of us have in learning. They want to act as though there are these ‘instincts’ we all have, that drive us to a significant extent – yet, we are born not even knowing how to walk or eat or hold things in our hands. Developmental psychologists are thrilled when they are able to actually point to something that may be an ‘instinct’ (i.e.: hang on to mommy really hard) and the evolutionary psychologists go on about how we probably evolved sexual behaviors, etc. Well, it’s hard to explain latex fetish (or any fetishes, really) as evolved instincts, when the object of the fetish did not exist 100 years ago.

@Marcus, #2: yeah… I have to agree that the idea of “instincts” is kind of… indistinct. I have personally observed lines of my goats who have an odd behavior quirk (they wring their heads, twisting the head up so the nose points straight at the sky then back down in a quick gesture) passed down from mother to daughter, and although that might seem like the offspring learns from the parent, I pull the kids at birth and hand raise them (this is to prevent a disease called CAE) so the kids are raised by me, not their mother, and they do not have the chance to observe the mother do the quirk, yet it often passes down the line. I can see where the idea of instincts came from and I can see that there is some support for it, but to apply it to complex behaviors like what people find sexually stimulating seems to strain the credibility quite a lot.

Figuring out what I like was the easy part. In fact, I didn’t even need to figure it out. I just knew what I like. Figuring out why I like some things is the hard part. For example, I have a fetish for long-haired men (the longer a guy’s hair, the sexier he is in my eyes). I have no clue where I got it. I just cannot remember anything that could have possibly caused this. I remember perceiving long-haired men as handsome already when I was still a child. I cannot remember any long-haired male who could have caused this (long hair being a very rare haircut for men to have).

Many of the things I like are pretty mainstream. For example, I perceive as attractive healthy-looking young people. There must have been thousands of images and experiences that overlapped to create those my preferences, which align with what majority of people tend to like.

I do have one thing that I can pinpoint to a particular childhood experience. When I was about 5 years old, my aunt started living with a man I didn’t like (here people don’t marry, they live together, they make babies, but they just don’t marry). At first, I simply didn’t like this person. By the time I was about 10 years old, he did some things that made me start to really hate him. The end result—I perceive as unattractive every single man who has facial features or voice similar to his.

I have also experienced my tastes changing after growing up.

For example, I grew up in a place where pretty much everybody is white. People of color were almost nonexistent here. By the time I was about 17, I realized that I perceive only white people as sexually attractive. My brain simply failed to register any non-white person as sexy. Luckily, by now I have gotten rid of this ridiculously stupid bias—my brain rewired itself after I spent a few months living in a place where there were also some people of other races.

Another example—I like the look of tailored suits. In my life there’s been one particularly hot guy who had a habit of wearing them. And I developed my taste for tailored suits after spending some time with that guy in my bed.

kestrel @#1

It’s funny how my experiences about crying are the exact opposite yet still very similar. As a small child I learned that I must cry in certain situations. If I accidentally injured myself, I had to cry in order to make adults come to me and help me. Also, if an adult was scolding me or yelling at me, I had to cry in order to make them stop.

By now this has turned into some ridiculously annoying reflexes that I still have. For example, if I walk on an ice covered street, slip, and fall down, tears will appear in my eyes almost immediately after my brain registers the sensation of pain. How much something hurts is irrelevant. Whether I get tears or not depends entirely on the circumstances in which I got hurt. I’m not a person who is particularly worried about pain. I even ask dentists to skip the painkillers altogether whenever I go to have my teeth fixed (in my opinion, painkillers are not worth the extra money dentists charge for them). It’s silly that something as trivial as slipping and falling on ice can make tears appear in my eyes, considering that in different circumstances some significantly more painful injuries fail to make me cry.

This reflex is even more annoying whenever I experience some person scolding me or yelling at me. You may call this toxic masculinity, but I simply refuse to let any human being see me crying. I hate being perceived as weak. Thus, whenever somebody starts scolding me, I have only two options: 1) go away, leave immediately before tears appear in my eyes, and before another person notices me crying, 2) argue or yell back. The second option actually works nicely, because tears will appear in my eyes only as long as I’m sitting silently and listening. If I argue back, I’m safe.

What else can I possibly do in such situations? What can I say, really? Explain and say, “I’m fine, I’m not sad or hurt or anything. In fact, I don’t really feel a thing or care about your criticism. This is just a stupid reflex lingering from my childhood experiences.” This won’t work. People have a tendency to assume that if you are crying, you must be hurt. If I tried saying “I’m fine” while having tears in my eyes, nobody would believe me anyway. Even though I really am fine. In these kinds of situations I don’t feel anything, my rationality or judgment isn’t clouded by emotions. It’s just a stupid reflex that makes my lacrimal glands secrete some liquid.

@Ieva Skrebele, #4: Pretty interesting how you learned to cry and I learned not to, and at a very young age! That’s also an interesting thing you said, that to quote:

“You may call this toxic masculinity, but I simply refuse to let any human being see me crying. I hate being perceived as weak.”

The idea that crying makes you appear weak is a pretty wide-spread idea, but I have to wonder where it comes from. I’ve met people who think laughing or showing any emotion denotes weakness, but that is not a common idea. When I think about it, I have to wonder why crying is perceived as a weakness. I think it can actually be a strength as it is a way of expressing strong emotion, but yet a lot of societies think it denotes weakness. Weren’t there societies in the past where crying was completely accepted as part of the range of showing emotion? And yet somehow this one, crying, got chosen as showing weakness. (And what’s wrong with being weak? I totally *am* weak, I’m very small and not nearly as strong as a lot of people!) Humans are so odd, sometimes…

Marcus, this is completely unrelated.

I flew to Copenhagen two weeks ago, and I sat next to a Danish couple. He looked like your older twin brother — the resemblance was striking; even the glasses he wore were similar to the ones I saw in your photos. Next day, I saw a guy on the street protesting the F-35 (he was leaving and packing up his sign, so I only got to take a glance, but it said “F-35” and “75 million” among other things), so I thought about you again. Later that week, I saw a bunch of swords, including a few short swords made of bronze, one brought some 3200-3500 years ago from present-day Hungary or Romania, and another one from Greece. They don’t come much older than that — it seems we started making swords around 1700 BC. (By the way, the early Danes seem to have liked bogs a lot: the entire prehistory floor of the National Museum of Denmark appears to be made of things they sank into bogs as offerings.)

So yeah, Copenhagen seemed like your kind of place.

There’s a big selection bias there. Bogs are great for preservation, so yeah, we find a lot of stuff in bogs, but it’s very difficult to say what proportion of “total stuff” it represents. There’s quite possibly entire fields of Northern European material culture that are drastically under-represented simply because those artefacts were less likely to preserved by ending up in bogs.

cvoinescu@#6:

Copenhagen seemed like your kind of place.

I’ve been there a couple times. It’s lovely and everyone is very nice.

Dunc@#7:

There’s quite possibly entire fields of Northern European material culture that are drastically under-represented simply because those artefacts were less likely to preserved by ending up in bogs.

… because the stuff that was in burning monasteries just didn’t last!

(They were just trying to rescue the stuff from the fire!)

kestrel @#5

I don’t have any clear memories from before the age of five. I only know that by the time I was five years old I already knew that crying was obligatory in order to get adults to do what I wanted. I had already learned that if there were no tears in my eyes, then adults would assume that whatever problem I had wasn’t serious enough to warrant their immediate attention. Basically, I had to deal with the same problem you faced—if a child isn’t crying, adults ignore them. Hence I learned to cry.

As I got older, things changed, and I started to hate the way how adults reacted upon seeing me crying. If my problem was something they could solve, it wasn’t that bad. But often my problems were something that no adult could possibly solve. In such cases I got words of pity. And those were a pain to deal with and listen to. I didn’t need words of pity, I somebody couldn’t offer me tangible help, they might as well better skip the display of pity. I don’t know how old I was when my attitude changed. I only vividly remember one case when I was eight years old and my mother awkwardly attempted to cheer me up and all I was thinking was, “When will you finally shut up? I know that you cannot help me in the given situation, so just shut up and leave me be.” I just don’t enjoy receiving pity.

I actually agree with you here. What you say is reasonable. In fact, trying to hide emotions, pain, problems, etc. can be a very stupid thing to do, because of the negative consequences—worsened communication with your loved ones who have no clue what’s going on with you, premature death caused by a failure to seek help in a timely manner, etc. bad consequences. But, unfortunately, we live in the kind of society that expects people, especially men, not to show tears. Failure to do so can also result in negative consequences, because, well, we just live in a society that perceives crying as a sign of weakness.

Some people prey upon the weak and the vulnerable. I developed my aversion to letting anybody see me cry at school. Back then I mostly ignored my classmates. They bored me, spending breaks between lessons reading books, writing poetry and doing homework was more interesting than talking with my classmates. Frankly, even staring out of a window seemed more interesting than socializing with other children. Me being alone all the time made me the prime target for wannabe bullies. I had to fend off them on my own, because I chose to stay away from everybody. I must admit that verbally humiliating bullies was a really fun pastime for me. However, I also had to be careful—I couldn’t allow them to perceive me as weak. If bullies had found out that it is possible to make me cry, fending off all of them would have become significantly harder for me. And this is not just bullies at school. Some adults also prey upon those whom they perceive as weak and vulnerable. My life is simpler if no asshole with bad intentions paints a target on my back because of a mistaken assumption that I might be as easy prey to mess with.

I also don’t like being perceived as emotional.* This is largely caused by sexist attitudes among people. I have actually heard a claim that women shouldn’t be allowed to work as politicians because of mood swings caused by their menstrual cycles. The implication being that an emotional person cannot be trusted to make any decisions.** The other implication being that all woman are emotional, because of their hormones.

And then there are also my gender problems. In a perfect world if I say that I don’t perceive myself as a woman, that alone should be enough for everybody to respect my choice and acknowledge my gender identity. Of course, that’s not how things happen in real life. I have had people question my masculinity. As if a right not to call myself a woman is something that must be earned through stereotypically masculine behavior and personality traits. I don’t like being perceived as feminine, and, unfortunately, many people equate “emotional” with “feminine.” (Which is stupid, I know.)

——

*Actually, I’m a very unemotional person. However, I have actually experienced people accusing me of being emotional simply because of how my body looks like.

**I don’t think there’s anything wrong with making decisions based upon your emotions. In fact, I’d say that’s the rational thing to do in life in some circumstances. If you let your emotions guide your decision making process (namely, you choose to do the option that makes you happier), it’s a reasonable thing to do, because it makes sense for humans to value happiness.