Warning: War, Death

Administrative note: I made an error attributing the movie and confused a different movie with a release of the same film under a different name. Explanation is [here] – in order to reduce confusion, I have done an edit-pass. If you see comments about how I am talking about the wrong movie, they are correct with respect to the initial version of this posting. Sorry about the confusion!

I don’t know if I have the necessary skill to convey how upsetting this topic is. I wish I could borrow the skills of Orpheus from somewhere, and get other people to watch it, get angry and scared, and – do something. I don’t even know what we can do, trapped as we are in the reality of nationalism and out-of-control militarism.

Threads is about the horrible deaths our political leaders have prepared for us.

If you don’t like spoilers, don’t read any further. But there’s really nothing to spoil. You already know roughly what happens.

In 1984 Mick Jackson directed a movie called Threads[imdb] – a docu-drama about the residents of Sheffield, England, and what they experience during a full-up nuclear exchange. It is not in the slightest bit entertaining. It starts off foreboding then gets worse, and worse, and unbelievably worse, then incredibly, deeply, horribly worse. At the end, where some directors might have tried to hook in a redeeming note, Jackson swerves sharply and makes things still worse.

Because, that’s about right. The whole time I watched Threads I kept thinking of Nikita Krushchev’s threat that “the living will envy the dead.”

Interspersed throughout the movie are still shots that are all the more disturbing because they are beautifully done. They make me want to hammer Brian Williams in the face with a brick, for ever saying anything as stupid as “guided by the beauty of our weapons.” [wp] Fawning media totalitarian proto-fascists like Williams, who accept and glorify the necessity of nationalized violence, are the facilitators that are going to bring about this sort of disaster, if or (more likely) when humanity finally decides to pull the toilet-lever and flush all of everyone’s hopes and dreams away.

Jackson sets us up for exactly that scenario. We meet a typical pair of English kids from the 60’s: they go to the pub, they drink, they make out in the back of his Cortina, parked on a pretty bluff with an idyllic view of the city of Sheffield. Well, it doesn’t seem idyllic, at first – it looks like a typical industrial town full of people hanging on the edge of working too hard, drinking their desperation away. The movie gets rolling slowly, and – did I mention? – it gets worse. Naturally, the girl gets pregnant, and there are some poignant “meet the parents” and “set up an apartment” scenes. Brilliantly interwoven in the ordinary dreariness of their lives are flashes of news: the USSR has invaded Afghanistan. The US issues an ultimatum and deploys B-52 bombers and troops. There are reports of skirmishes. Life in Sheffield stumbles on, gut-shot, but not knowing it yet.

As the tension between the USSR and US, dimly glimpsed in flashes, ratchets up, the viewer begins to feel a very real and inescapable dread. I’ve seen scary movies that build tension but nothing like this, before. Perhaps the worst part is that the fragments of news could so easily match what is coming from Korea: both sides rushing troops to the area, chest-puffing, threats. Jackson’s decision to set the film in Sheffield, which is mostly uninvolved in the war, was doubtless because of the practical exigencies of movie-making and his target audience – but the sense that all of this war stuff is going on somewhere else, is brilliantly rendered in the half-heard snatches of news. I spend a lot of time trying to hear those fragments about Kurdistan, Afghanistan, Korea, Nigeria – and reading between the lines in Threads is so well done there were times that my hair literally stood up on my neck. It’s all “somewhere else”, until – wham.

We see a bit of the “preparedness” efforts of the government – the town administrator is told to begin storing medical supplies, water, gasoline, and so forth – he’s a well-meaning civil servant with no idea what is looming over him. But, then, nobody does. That’s why Watkins made the movie, after all. In the last few months the US has seen images of hundreds of thousands fleeing by car, of the traffic jams and shortages: now, imagine people trying to flee from something from which there is no place to hide. There is another movie in this vein, Miracle Mile [imdb] but somehow it becomes a disaster movie with a bit of action flick hidden in it. Threads has this methodical rhythm that somehow makes it clear that nobody is getting out of anywhere – I think a lot of that is a result of positioning the film in Sheffield, far from where anyone would expect war to come, and probably far from where anyone expected to do anything about it.

That’s one of the most powerful messages I took away from the movie (other than “the living will envy the dead”) – the vast mass of us sit in the shadow of this horrible thing our leaders have planned for us, and we feel that there is nothing we can do. Or perhaps there is nothing we should do because it’s all so far away. But they built this for us – they planned this for us – they used our money and our work to fund it, and the very worst of them talk about it as though it’s a casual game of golf. No halfway decent human being should countenance this thing for anyone.

We, the people of the world, should rise and rip our political leaders to bits for preparing this bath of fire for us.

Naturally, our political leaders have bolt-holes, where they expect they can hide and weather out the worst effects of their utter failure. Jackson doesn’t address that directly, but obliquely and powerfully shows us how that works, as well: the mostly well-meaning political leaders of Sheffield take shelter in their command center under the town’s office building, and are trapped when the building collapses over them. They die slowly and horribly. But so does everybody else.

The bonfire of nationalist vanity

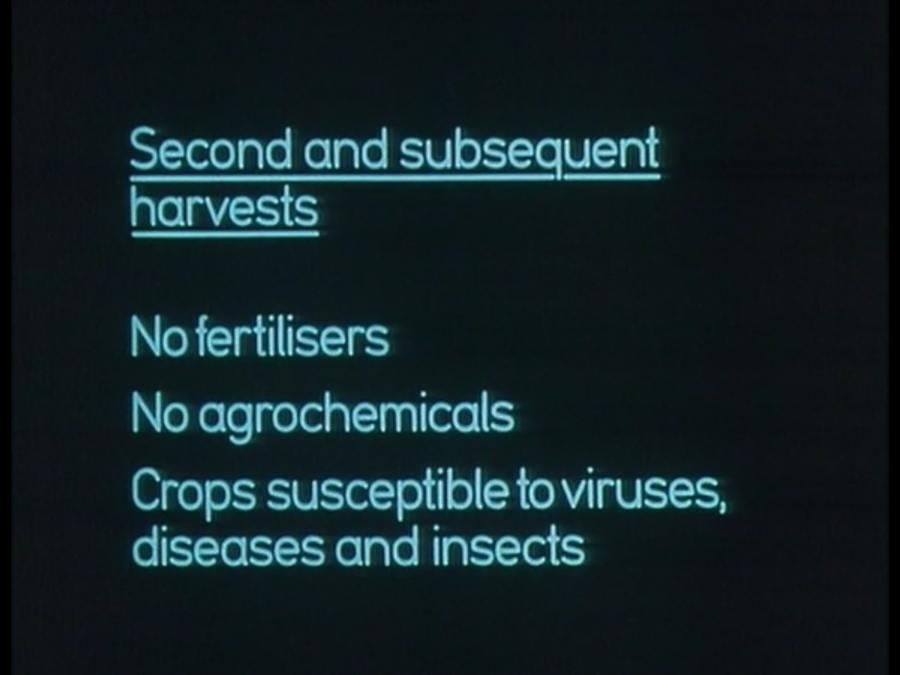

The story follows its little cast of characters that eventually dwindle to one, the young pregnant woman. Then, the documentary aspects begin to pop in, with freeze-screens that blandly state facts that are so scary your mind wants to crawl someplace safe instead of reading them. I imagined I had a pretty good handle on nuclear war, but there are things I hadn’t thought of, which Jackson’s researchers did.

We’ve all heard of nuclear winter, but I’d never thought of the plagues of rats and flies that would follow having 20 million unburied corpses (never mind the sheep, cows, etc) or the side effect on agriculture.

There was a report yesterday about an intensive care unit in a hospital in Puerto Rico that suffered a power failure and all the patients are now dead. In Threads we see doctors throwing up their hands in despair at the uselessness of trying to help patients who will die from radiation exposure. The medical infrastructure at Hiroshima and Nagasaki collapsed, similarly. What Watkins makes us see is that it’s not a partial collapse, like “no power or water” but a total collapse. “No nothing.” Our modern civilization is tightly integrated and god damn it we depend on each other – it’s like a Jenga tower – politicians imagine that they can just destroy part of the world without affecting the rest.

Jackson’s projections are that, after radiation and secondary die off, nuclear winter and the destruction of agriculture and supply, England would be back to medieval-level population again, 30 years after the war – about 1.2 million people. England, frankly, isn’t much of a target, so their suffering would be long-term collapse. That saying about “bombing someone back to the stone age”? It’s not funny or accurate: it’d be early iron age.

I have more in common with a typical North Korean peasant than I do with Kim Jong Un or Donald Trump or any congressman. So, do you. We are all living under the threat of this thing, built by power-loving politicians and their Renfields, in order to make themselves more important. They are the same people who talk casually about “axis of evil” when they’re actually founding members of the axis, themselves.

In the last few weeks two things have happened:

- The Nobel Peace prize was given to the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons [nyt]

- 120 countries and the United Nations adopted a nuclear disarmament agreement, which was ignored by all of the 9 declared nuclear powers. [pri]

A third thing that’s happening is Donald Trump will continue funding the US’ development of new weapons – a $1.5 trillion dollar expenditure – which will almost certainly mean the US will be violating the limited test ban treaty. We need to finally acknowledge that the nuclear powers (in spite of what they said in the Non Proliferation Treaty [npt] they shoved down everyone else’s throat) never intended to do anything but achieve and maintain a monopoly. Non-nuclear states are obliged not to make or develop nuclear weapons, but the nuclear powers will continue to maintain and upgrade their arsenals. And when was the last time that the citizens of the USA or Russia had any say in whether more nuclear weapons would be developed? In other words,

“I am not an Athenian or a Greek, but a citizen of the world.” When it comes to nuclear war, nobody is isolated.

Compared to the hostile powers our own leaders have arranged against us, any disagreement any of us might have with a citizen from another country is piffle. ISIS? They are nowhere near the threat to anyone that the commander of the US, North Korean, Russian, (on down the list) is. Sure, they are repugnant, cruel, murderers – but they are rank amateurs compared to our leaders, who are prepared to murder on a vaster scale and who, in fact, have pretty much murdered ISIS (and 50,000-100,000 noncombatants along with them) I can negotiate with ISIS – probably it wouldn’t go well, but I can try – militant nationalism doesn’t permit negotiation at all: they make us pawns in their game and they’ll throw us in the fire at any moment without feeling particularly bad about it (unless it’s bad for business).

Why can’t we rise up and put these motherfuckers up against a wall and shoot them?

[Edited] Peter Watkins [I was under the mistaken impression that Watkins directed Threads] directed Culloden [imdb] and La Commune [imdb]. I’ve seen Culloden and it’s excellent and unsettling. Imagine if a documentary film crew were present at the battle in 1746, and interviewed some of the soldiers involved, then followed their experience in the battle. Punishment Park [imdb] is a docu-drama about a hypothetical 1970s where the government cracks down on Vietnam War protesters by killing them.

“The living will envy the dead.” Krushchev may not have said that. But, he should have: [wp] he, and John Kennedy (who attributed that comment to him) were some of the monsters that helped build humanity into this corner, in service of their vanity, greed, and love of power. Threads was made in 1965, and Krushchev allegedly said that in 1963; I suspect that phrase was rolling through Watkins’ mind the whole time.

A minor clarification: I do not support nationalized violence; it is predicated on the idea that those people over there, who live within those lines on the map need to be collectively hurt or killed because of those lines on the map. I am in favor of personalized violence, when it’s defensive it can be the only effective response to aggression. I consider the political leaders who have built and who maintain the world’s military balance to be aggressors against me. I take this personally.

Aren’t you confusing War Games with the 1984 film Threads? Same setting.

I saw Threads about the same time as I saw Testament. The first was excellent and disturbing (as was Culloden), the second simply devastating.

Miracle Mile was good.

Rob Grigjanis@#1:

I do appear to be confused! Argh! I seem to have gotten the idea that Threads was by the director of Culloden.

Anyhow: review is about Threads and I will sort it out when my plane lands in Chicago.

Let’s not forget the macho insecurity which tends to abort second thoughts about launching wars:

Trump adviser Roger Stone calls James Clapper a ‘c*cksucker’ for coming out against nuclear war.

Nitpick: The War Game (1965, mono, set in Rochester in Kent) and Threads (1984, colour, set in Sheffield in the West Riding of Yorkshire and the Peak District up the road from me) are two different films.

For anyone interested, there’s a copy on Vimeo.

“Threads” was on TV sometime in the 1970s, though I was too young to (understand) appreciate it or know what I was seeing. AV Club covered “The Day After” and “Miracle Mile” recently. “Threads” was mentioned by several people in the comments.

The nuclear disaster movie from the 1980s that stuck with me was “Special Bulletin”. (Rotten Tomatoes) It was (semi-spoiler) not an ‘end of the world’ film, but it sure as shootin’ was “What the hell do we do now?” It would have been more effective without the three minute voiceover of the “future”.

Another film worth noting is the semi-documentary Countdown to Looking Glass, a film about an escalating political confrontation that ends in the worst way possible. Sorta like now. And it involves most of the same players – Saudis, Yemen, Russia, the US.

We were shown the 1965 The War Game in General Studies at school in sixth form (so when I was sixteen or seventeen in the late 70s) and it left those of us with any imagination terrified. I particularly remember a line in the list of what would happen to you at different distances from the blast, that at such and such a distance your eyeballs would melt … it horrified me then and horrifies me now. At the time although it had been made for showing on TV ( I think the BBC) it had not been bradcast as it was considered too graphic, our teachers (most of them left wing in British terms) thought we ought to know the reality of what nuclear war might be for us.

It’s okay, Jazzlet. If your eyeballs melt, pretty much the rest of you is also going to melt is very short order. You won’t have much time to really freak out about it.

I have several times noted the pervasiveness of this sort of theme in the culture of the UK in the decade leading up to my birth (mid 80s). People fifteen, twenty, thirty years older than me occasionally comment on the mood of despair that nuclear proliferation issues carried up until the mid 80s. One of Charlie Brooker’s TV analysis programmes noted that he grew up terrified of nuclear war thanks to what he saw on TV at a young age (though, these days, by comparison, he’s scared of pretty much everything given the barrage of awfulness we get on 24 hour rolling news). When I first saw the final episode of Carl Sagan’s Cosmos I recognised the same concerns, so it was no doubt present in the US too.

Thing is, it seems like a different world to the one I grew up in. The TV of the 90s and 2000s carried nothing like this. I still find it difficult to think of nuclear war as a real and devastating possibility – to those of us born after about 1980 it was the dread of our parents’ generation that never happened, if it was anything at all. Yes, we knew that nuclear weapons still existed, but it was generally assumed that, what with everyone knowing about nuclear winter and how using them would be suicide for the whole planet, nobody would ever dare. I still like to hope that such a thing will, in fact, turn out to be true.

No, to us the looming threats to continued human existence were climate-based – the hole in the ozone layer, the Greenhouse Effect and Acid Rain, as we learned about them. Climate Change in the modern idiom. Which were painted as the unwanted long-term side-effects of generalised human greed and ignorance, rather than of specific belligerence and political brinkmanship on the part of particular nations and individuals.

So it’s actually quite bizarre for people of my generation to start seeing the news and the commentary on it looking like those “oh, what a quaint and unusual time the bomb-scared seventies were!” videos we used to raise an eyebrow at when we were younger. What to the generation above us is an uncomfortable reminder of the bad old days is to us something we only learned of as ancient history.

OK, I see what happened here: when I first obtained Threads a couple years ago, I got it with Culloden and somehow brainfarted that they were by the same director. That mistake being in my mind for some time, I didn’t question it further; when I was looking for the links to add to the IMDB entries, I actually went at it from “director of Culloden” angle, thereby perpetuating and expanding my mistake – especially when I saw the cover of The War Game which sports a still that is similar to the stills from Threads.

Confirmation Bias kicked my ass!

My errors are substantial and are larded throughout the piece; normally when I make a small mistake I prefer to leave it in the comments and not run back and fix things, but I think this one is substantial enough that I want to fix it throughout. I’m going to do a patch pass through the whole article and will add a bit at the top referring to this comment in case anyone is confused by the other comments. It’s that or call you all “fake news” and purge any of you that don’t rally ’round the doctrine of my correctness.

Daz: Uffish, yet slightly frabjous@#5:

For anyone interested, there’s a copy on Vimeo.

Ah, thanks! Sometimes it’s hard to find this sort of stuff. Because I’m on limited bandwidth in Verizon country, I tend to scour for DVDs on ebay and I’m not very effective at finding online versions of films.

Raucous Indignation@#8:

You won’t have much time to really freak out about it.

There are a fair number of accounts of the aftermath of Hiroshima, featuring people whose eyes boiled but they managed to duck the shockwave. So they lived a few days before dying of infection, burns, and radiation. That’s a pretty unpleasant interval. The descriptions from Sunao Tsuboi [guardian] are the stuff of nightmares. It sounds like the shockwave knocked some people’s eyes right out of their heads.

Rob Grigjanis@#1:

I saw Threads about the same time as I saw Testament.

I got the two at the same time; Threads stayed squirrelled away on my server for a couple years before I could bear to watch it again and talk about it.

Testament was OK but I felt it deliberately downplayed the seriousness of nuclear war: let’s just have an isolated area where everyone dies slowly (but cleanly) from fallout. It was poignant, to be sure.

cartomancer@#9:

I still find it difficult to think of nuclear war as a real and devastating possibility – to those of us born after about 1980 it was the dread of our parents’ generation that never happened, if it was anything at all.

The big difference is that the US and its allies have since positioned themselves to nearly be able to win a nuclear war. The forces are now sufficiently imbalanced that there is virtually no way that the Russians or Chinese would even consider a war to be ‘winnable’. Unfortunately, it means that the whole rest of the world is on a back foot defensive posture expecting US aggression.

I have been meaning for some time to do a posting about the changes in the US nuclear arsenal that have been quietly put in place since 2005 (or so) and what they mean. The short form is that it’s bad, and it’s getting unbelievably worse.

Raucous Indignation@#8:

As Marcus says you will indeed have time to think about it, and to hope someone does the decent thing and kills you before the rest of effects start to be felt.

Marcus @13:

Well, it focused on one family, so yeah, no statistics or details of crop failures or nuclear winter, etc. Everyone you see in the movie dies, or will die shortly. Before that, links to the outside world drop to zero. The implication is that maybe everyone snuffs it. Downplayed the “seriousness”? Er, OK.

As for “dies slowly (but cleanly)”. Yeah, I guess they could have been more graphic for the gamer generation, but watching a little boy shit his short life away didn’t seem very clean to me. Or watching a mother tell her dying daughter about the facts of a life they both knew she would never have. We obviously have different notions of “clean”.

Needz moar scary data, screamin’, and rottin’ corpses, I guess.

Just to pour a little more gloom on the fire: remember, this film was made at a time before computers were ubiquitous. At the time it was shown on TV, I was taking a vocational course in stock control and admin. And I’m quite probably one of the very last intake to have learned how to control the flow of resources using tools—card files, rolodexes and so on—which didn’t rely on the widespread availability of electricity. If anything, the effects of “no power” now would be even more disastrous now than then.

I was born in 1960, so I remember the dread well. I’ve always thought the MAD policy was probably the best option.

In passing, check out “Operation Chrome Dome”.

Rob Grigjanis@#16:

Well, it focused on one family, so yeah, no statistics or details of crop failures or nuclear winter, etc. Everyone you see in the movie dies, or will die shortly. Before that, links to the outside world drop to zero. The implication is that maybe everyone snuffs it. Downplayed the “seriousness”? Er, OK.

That’s what I meant, I suppose. Implying that everybody dies, offscreen, but keeping the view focused on one family, that seems to me to be the very essence of minimizing the experiences of everyone else in the world. It’s a way of getting the point across, by use of negative space, I suppose. Don’t get me wrong, I thought it was a good movie, and very well-acted. On The Beach likewise – “let’s contrast the normalness of the flashbacks with the reality of the post-war irradiated death-world.” It’s easier to swallow – why?

As for “dies slowly (but cleanly)”. Yeah, I guess they could have been more graphic for the gamer generation, but watching a little boy shit his short life away didn’t seem very clean to me. Or watching a mother tell her dying daughter about the facts of a life they both knew she would never have. We obviously have different notions of “clean”.

Probably. But I think we’re talking past eachother: the mother/daughter scene or the dying boy scene are a way of getting at the interpersonal impact of the war, of which there would be plenty, but it relies on personalizing something that I think is significant (and scary) because the destruction is impersonal and total. Perhaps that’s my own emotional bias to how I react to these movies – it’s not the fire and the corpses and whatnot, it’s the randomness and totality of “everyone is more or less instantly fucked, forever” that is (for me) the real message of nuclear war. Testament and On The Beach and to a lesser degree Miracle Mile are movies about the individual confronting the event; that gives the characters a chance to say their goodbyes, have their touching noble moments, etc. The awfulness of nuclear war is that, for most people, that’s a lie: you go from having a fairly typical day to utterly fucked, and it’s utterly random who gets to say goodbye and be noble, and it doesn’t matter at all. As I write this, I realize I didn’t explain myself well to begin with – when I used the word “downplaying” I meant that Threads demonstrates how a nuclear war obliterates everyone’s meaning and humanity, which is what I expect it will do, and that’s what holds the greater terror for me. Other movies about nuclear war are about the protagonists finding meaning in the face of the event. I think that tends to minimize the event.

Needz moar scary data, screamin’, and rottin’ corpses, I guess.

Uh, no.

You seem to be implying that I’d like a special-effects fest, which is missing the point. Perhaps I didn’t make that point well enough.

jazzlet@#15:

As Marcus says you will indeed have time to think about it, and to hope someone does the decent thing and kills you before the rest of effects start to be felt.

Some of the things the Hiroshima survivors endured, and survived, seem like the sort of thing that would make one wish to die while experiencing them. Yet the survivors didn’t. The bomb killed 75,000 immediately, and that number again died over the next few days. There were over 100,000 survivors who were injured to some degree or another, and did not die, and got to live lives that were forever changed by the experience. To me, that’s what’s so scary and stupid about nuclear war: imagine having a day that had that level of random, pitiless, meaningless impact on everyone on earth. Some of the living would definitely envy the dead, but a lot of the living would just be puzzled, hurt, bereft, left with this irreversable decision that would never make sense to them.

John Morales@#18:

I was born in 1960, so I remember the dread well. I’ve always thought the MAD policy was probably the best option.

MAD was the only thing that made sense, given that political leaders would never relinquish their grip on power and assume that other political leaders would act likewise – which is probably a safe bet.

As I implied to cartomancer@my #14, I think MAD is tilting away from MAD and toward “if the US tries anything, we’ll be able to hurt them badly enough they regret it” which is a difference. I’m afraid eventually we’ll see US leaders that decide that a few megadeaths is a fair price for someone else to mostly pay.

In passing, check out “Operation Chrome Dome”.

I’m familiar with Chrome Dome and the broken arrow incident that occurred. I don’t see any movie or documentary by that title. Do you have a link to it you can share?

Sorry, I would just be Googling for it, Marcus.

But yes, the specific incident I had in mind was this one: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1966_Palomares_B-52_crash

Yeah, I was born in ’73, and I certainly remember it as a constant background threat that impinged very heavily on the popular consciousness… Even as a kid, there was no escape – you had noted children’s author Raymond Briggs (creator of such light-hearted, whimsical books as Fungus the Bogeyman, Gentleman Jim, and The Snowman) producing his horrifying study of the vacuousness and futility of the government’s attempts to prepare people in When The Wind Blows, you had the controversy over the government pamphlet that he was referencing (Protect and Survive)… Hell, in primary school, probably around the age of 10, we got to play with a computer program (on the BBC B)that let you input a target location and a megatonnage and it would show you the various effect radii on a map… Given that we lived around 30 miles from Rosyth naval base, which at the time was a key maintenance location for the UK’s nuclear submarine fleet, I was pretty sure that I would have died in the first strike – and that was a good thing.

It’s really hard to convey what it was like to someone who didn’t live through it.

Dunc, you ever play Nuclear War?

Dark fun.

Born in 1975, I’m old enough to remember the tail end of the Cold War in the 80s and the fears of nuclear war that pervaded society then. The weird thing for me is that while I was an anxiety- ridden little kid, I didn’t feel much anxiety about nuclear war. Perhaps it was because it was so huge and impersonal, like an asteroid strike from outer space, nothing that I could do anything about. My childhood anxieties were focused more on the personal, on things that I thought I could do something about, or on things that would target me personally. By the time I grew up and started to worry about broader issues, the fear of nuclear war had receded.

Marcus I know people survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and I suppose given the disparity of arsenals MAD isn’t going to happen, but I am used to thinking in terms of MAD. I don’t know how much difference a ‘limited’ nuclear exchange would make to the country that was the target of the US. I don’t know enough about how that would affect the rest of the world either, it’s one of those things that I haven’t looked into. I admit I find it difficult to think about this, it’s just so insane that anyone might do it thinking that they would be ok so fuck whatever country is pissing them off.

jazzet@#26:

it’s just so insane that anyone might do it thinking that they would be ok so fuck whatever country is pissing them off.

It’s way worse than that. I don’t think I want to spoil it for you, yet. Eventually I’ll do a posting on the SIOP but I can’t stomach it right now.

People survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki because there was a “rest of Japanese society” for them to fall back on. The full on nuclear strike scenario specifically overkills areas that would be critical to reconstruction: power, water, transportation. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were horrible but the survivors didn’t face starvation. When you look at the scale of the US’ current arsenal – about 7,000 deployable warheads – it can only be interpreted as telegraphing an intent to obliterate entire civilizations. Including our own.