There’s an important piece being published at The Guardian, regarding the CIA’s attempt to conceal its torture program, and how congressional investigation was stymied (and allowed itself to be).

Most of it is material you should already be familiar with:

- CIA tortures people

- CIA keeps meticulous records of the torture

- CIA realizes that was a naughty thing

- CIA deletes records

- Congress begins investigation

- Some records are found

- Investigators begin studying the materials that are found

- The materials vanish from their computers

- The computers were provided and managed by the CIA

- The investigation is stymied

- The materials are still vanished

- Much hand-wringing

- We must not look backward, we must move forward

There are parts of the story that keep jumping out at me, parts which hint tantalizing at deep reservoirs of festering bullshit that the investigators surely know exist, and have chosen not to notice. For one, as before, there is the issue of backups. The Guardian’s story describes how investigators were given a shared secure(well, secure-ish) network by CIA, with documents dropped in from the outside for the investigators.

Workflow #1

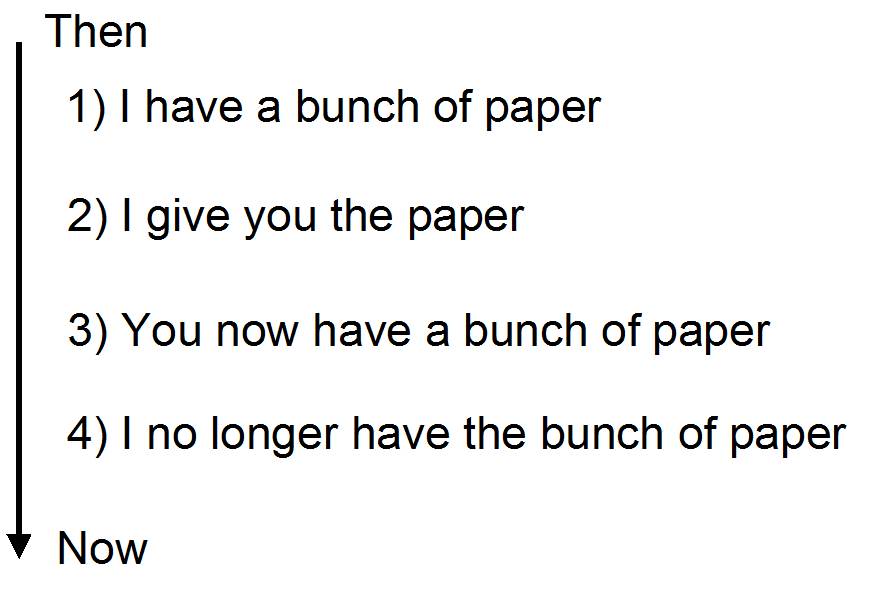

Here’s how exchanging documents looks in paper:

At least that’s how things looked back when Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura was nearly lost – that was a downside of the medieval approach to manuscript: it was manu and scripted and they didn’t have digital copy machines which are basically a scanner connected to a computer connected to a printer.

workflow #2

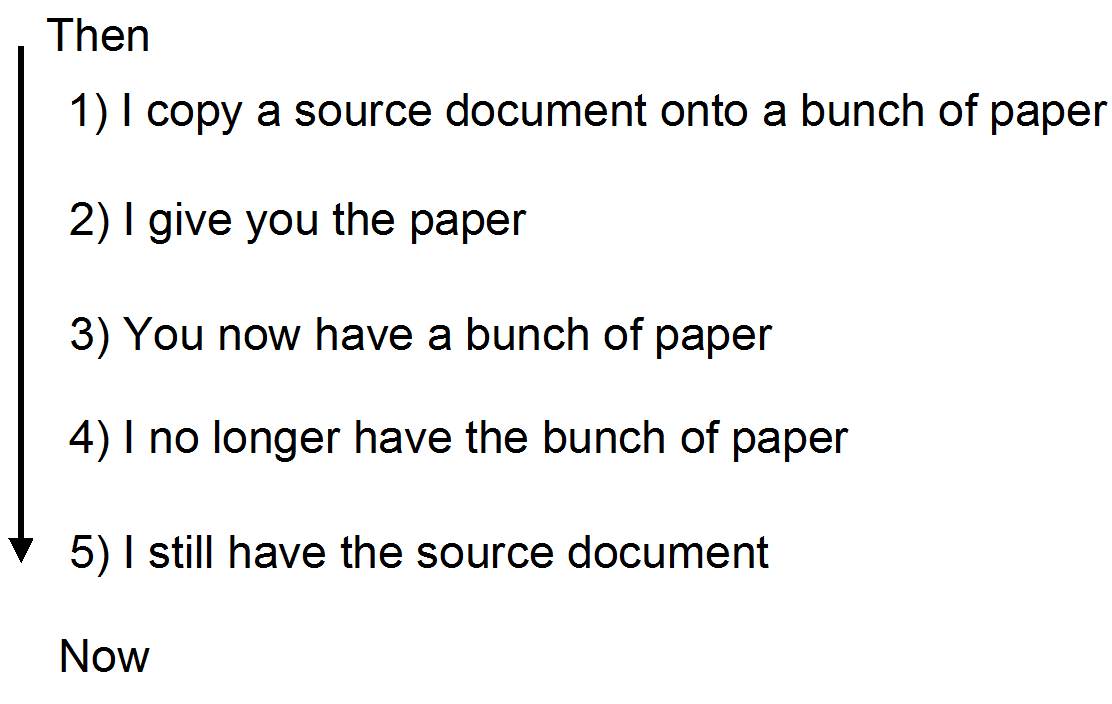

What “giving someone a document” actually looks like is Workflow #2. For some reason, the government wants us to pretend, along with them, that Workflow #1 is how documents move, whereas anyone with any experience with actual documents knows it looks more like Workflow #2.

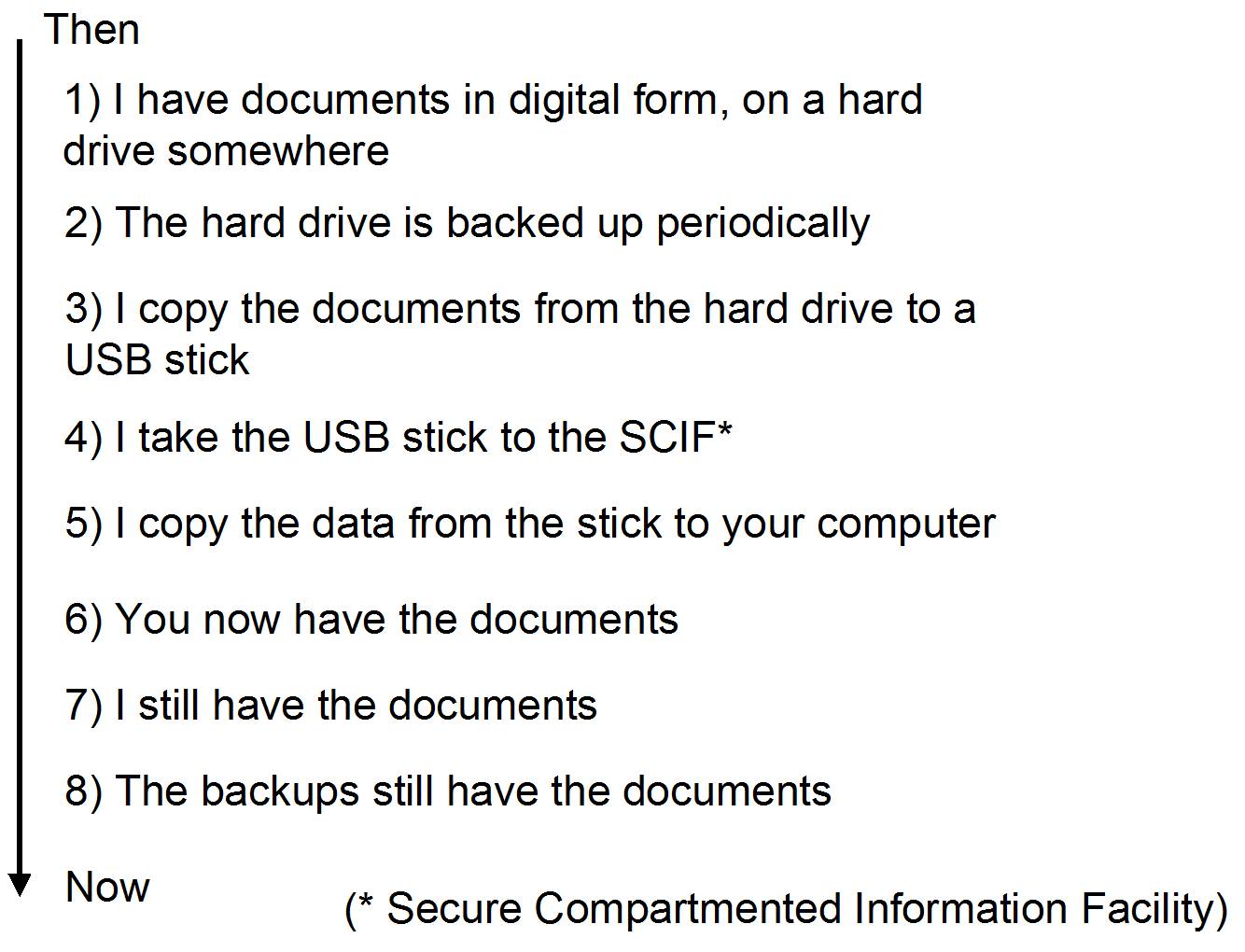

Of course it’s not really like Workflow #2, at all. It looks more like Workflow #3:

Just to be academic about it, in Workflow #3 there are now 4 copies of the documents: one on my hard drive, one on the backups of my hard drive*, one on the USB stick, and one on the computers in the SCIF.

Workflow #3

One of the key points that this scandalous story goes along with is the idea that data is easily destroyed, when all of our computer systems practices and processes are designed to make every effort compatible with convenience to ensure that does not happen. But, what baffles me is why the Guardian’s reporting goes along with the CIA’s utterly bizzare lie. When the data disappeared off the shared system, the CIA says “Oh, it’s gone now” and the congressional investigators stare sadly at the table, “yup, life sucks.” Are you fucking kidding me? Try this: “Get me another copy, even if you have to pull it from backup.”

There is another lie that is embedded in all of these stories: people saw the videos, and saw the torture. The guys pouring the water weren’t the guys running the video camera. The guy who copied 90+ whatever tapes of torture porn and sent them to Washington from Thailand was not the guy who poured the water, either. Were the 90+ tapes of torture porn the only copies, or where they 2nd generation data? Didn’t the CIA track who had access to the tapes? The very fact that enough people knew of their existence to make sure they got wiped means that enough people knew of their existence to make sure they got wiped because they saw them, or otherwise came to know that there was an archive of torture-porn. From what we know of the mindset of torturers, I’d bet some of my body-parts that some sick thug still has a copy, either as insurance or because they think it’s cool. It’s like serial killers: they like souvenirs and if you’re dealing with a deliberate psychopathic killer, they almost always keep a scrapbook full of memories.

Actually, some of the people who did the torture are still alive and well and probably collecting CIA paychecks. Others, who destroyed the tapes** are known to the CIA and (to some degree) to congressional investigators. Destroying the tapes does not cause their personal experience to somehow vanish from their minds. “Ooops! I deleted the evidence, now suddenly I can’t recall anything at all!” That’s not how human memory works. That’s not how data moves.

That’s certainly not how bureaucracies work. We can be certain that the CIA has information in its institutional memory about who did what, and when. People submit expense reports that they flew to Thailand and stayed at Facility X for 3 weeks, people get paid to clean up Facility X, people provide food, people sell the gear, people keep the lights on, none of this stuff happens in a vacuum. Sure, it happens in secure compartments (that’s how security is done!) and covert operations are performed on black budgets that don’t have line-items like: “nylon straps, 5ea, $400”, “therapeutic backboard, 1ea, $3200” But someone approved those expenses, and the people managing the logistics of the torture program could probably tell you damn near as much about what happened as the people being tortured, could. (By the way, since we are talking about a high crime, here, why hasn’t law enforcement done what they always do in pretty much every case: ask the victims? “Hey, can you look at these 30 pictures and point out the guy you say waterboarded you?”)

They called it the Panetta Review because the agency prepared a summary of its renditions, detentions and interrogations work for Director Panetta, who had come to Langley after Obama shut the program down. One version was a Microsoft Word document, clearly a draft, with the function allowing users to see each others’ changes enabled. Another version, apparently more final, was a PDF. Iterations by CIA were clear on view: “You could see the attorneys looking at it and saying, ‘Well, let’s make sure we can back this up, can you add more citations?’”

So, that’s one point. To summarize: the institutional memory of the CIA is not magically wiped clean when a few tapes are destroyed. Everyone, from the CIA to congress, to (unfortunately) The Guardian’s reporters – are accepting a lie that doesn’t stand up to a few seconds of scrutiny. President Obama, the Harvard-educated lawyer, “we tortured some folks” even starts talking like a dumb hick to help sell the “gosh we’re just so forgetful down here, we’re all a bunch of chucklefucks and you should see those CIA guys, they can’t remember what they had for breakfast, let alone who they strapped down and waterboarded over and over, nyuk, nyuk. What was I saying?”

It turned out that those contractors the committee thought the CIA hired to aid in collecting responsive documents were also acting as gatekeepers. They would review torture documents three times before disseminating them to the investigators to determine not only relevance, but whether higher-ups ought to make the call to turn them over. In some cases, the chain went up to the White House, to review for executive privilege – advisory conversations with White House staff, a broad category that typically keeps a record within the hands of an administration.

Oh, in other words, the “gatekeepers” know everything that was in all the documents. So we’re supposed to pretend that nobody knows anything, within a few sentences of the gatekeepers knowing everything. If this were a criminal investigation (which it should be!) that would be called “conspiracy” – except in this case, everyone including the reporters is in on it.

I have an idea for how you could learn everything: offer to waterboard the “gatekeepers.” We wouldn’t actually have to do it, because they already know they’ll break and spill everything when the Saran-wrap goes over their mouth.

The other head-explodingly horrifying bit of the story is tiny. It’s kind of tucked over to the side, like a razor blade hidden in a slice of chocolate cake. Quoting:

The lack of communication had serious consequences. Without Durham specifying who at CIA he did and did not need to interview, Jones could interview no one, as the CIA would not make available for congressional interview people potentially subject to criminal penalty.

Got that? The CIA was allowed to tell the congressional overseers that they wouldn’t make anyone available to talk to the overseers who might potentially be subject to criminal penalty. That is the literal definition of “above the law” – hey, I’ll let you talk to people, sure, except I won’t let you talk to anyone I know is a criminal. Doesn’t that very construction mean that the CIA knows who is potentially subject to criminal penalty? Hint: those are the people you should be talking to. The CIA’s got a serious epistemological problem, here, and everyone is letting them walk away with it.***

It’s like one of those bad cop shows (except without Ice-T) where the prosecutors offer immunity to a complete douchebag to get testimony. Except apparently congress accepted that, the investigators accepted that, and The Guardian’s reporters just let that rather important point slide by as if it’s just another bit of landscape seen through the window of a fast-moving train.

(* Nobody competent does all their backups to a single medium. We can refer to the “backup copy” as if it is a unitary thing but “backup copy” actually consists of dozens or hundreds of copies over a window of time.)

(** Seriously: are we supposed to believe that the CIA has a VHS videotape recorder spinning tape of torture sessions, and that someone got their hands on the tapes and ordered them destroyed? That’s also bullshit. The tapes were produced at a “black site” in Thailand, but was the original source material tape? Or was the camera recording to a hard drive and the tapes that were destroyed copies? See Workflow #2. Either way: someone made the tape and that person’s identity is known to the CIA. Part of the dance*** being danced here is that destroying one set of copies of the tapes somehow causes everyone involved to forget what happened, too. There are loads of witnesses: ask them. They’re shameful motherfuckers who are keeping silent to protect themselves and their criminal co-workers, and they’re convincing themselves its “national security” not self-interest.)

(*** Traditionally, Washington analysts would call this “Kabuki Theater” except that Kabuki is actually an art-form and it’s more accurate to call these “flat out lies” or, perhaps, “Gives me the lie i’ th’ throat as deep as to the lungs? Who does me this?“)

Technically it wasn’t paper when Lucretius’s manuscripts were circulating during the Central Middle Ages – it was parchment…

cartomancer@#1:

Yes, you are right.

And technically, I suppose a monk is a “scanner attached to a computer and a printer”

Shouldn’t they get charged with false imprisonment for holding in information that we all know wants to be free?

Who would they whistleblow to? The country’s the one committing the damn crime!

#3

He’s certainly a “digital copying machine”, given that he uses his fingers.

And for Lucretius we almost certainly are talking monastic scriptoria (Lobbes in modern Belgium if I remember correctly), but I would be remiss as a sometime medievalist if I didn’t note that after the late twelfth century there was far more manuscript copying done by university stationers’ companies, with their production-line pecia system, than by monasteries.

Shiv@#4:

Who would they whistleblow to? The country’s the one committing the damn crime!

The country is clearly divided about whether it was the right thing or not. I’m sad to say that public opinion appears to be flying the wrong direction. But international law and opinion say otherwise. The obvious thing to do would be to dump the information on the internet for the people to sort through. I would have said “wikileaks” but they appear now to be playing politics themselves. That’s one of the problems with the public whistle-blowing. Although, ultimately, the reason the state reacts the way it does to whistleblowers is because they can. If there were thousands of whistleblowers, they couldn’t.

There should be tens of thousands of whistleblowers. I would guesstimate that at least 1000 people in CIA know what happened. 500 were involved in the torture or the logistics or approval or cut orders.

I know it’s tangential to your point, but the statement, “[A]ll of our computer systems practices and processes are designed to make every effort compatible with convenience to ensure that [destruction of data] does not happen,” is not correct. In fairness, it was at one time a pretty accurate statement, back when nobody took electronic records very seriously as “records” in the formal sense. But today’s records management systems (where by “systems” I mean “policies, practices, procedures, and technologies”, not “computer programs”) are devised with different goals.

Quick caveat: I have first-hand experience with the issue in a public records context, and second-hand knowledge of how this is handled in certain high-stakes private organizations like major law firms. I *don’t* have any particular knowledge of how things work in classified / national-security contexts. I *imagine* that the principles are similar, but that implementation lags some years behind the “open public sector” in practice, because “not-invented-here” and “our-needs-are-special.”

In any case, in “my” world, the goal is not data preservation per se; rather, it’s conscious control. We want to define policies about what *is* kept and what *is not,* and to ensure that those decisions are ruthlessly enforced. That is, if we intend to preserve something, it must be preserved; if we do *not* intend to preserve something, every trace of it must be expunged (backups and all).

Again, all of this is tangential to your point — which is, I gather, that there’s a lot more we could learn about the CIA’s program if we were to conduct a serious investigation, as opposed to the gentlemanly “review” we have so far. (And that it’s kind of irksome that the press doesn’t seem to notice the difference.)

cartomancer@#5:

We can also be fairly sure that whoever copied De Rerum Naturae didn’t destroy the original when the copy was complete, like they apparently do in the CIA.

that guy on the internet@#7:

the statement, “[A]ll of our computer systems practices and processes are designed to make every effort compatible with convenience to ensure that [destruction of data] does not happen,” is not correct. In fairness, it was at one time a pretty accurate statement, back when nobody took electronic records very seriously as “records” in the formal sense. But today’s records management systems (where by “systems” I mean “policies, practices, procedures, and technologies”, not “computer programs”) are devised with different goals.

I packed a lot in to “compatible with convenience” but, yeah. If I had been trying to be exhaustively accurate I would have probably said “convenience and policy” But, I think I will let my point stand. Even organizations that have specific retention policies do not employ hard drives that don’t try to remap bad sectors, document editors that do not attempt crash-recovery, make no effort to curate and track revisions, etc. The Guardian article appears to be saying that there are PDFs of the Panetta report: what produced those PDFs? Nobody sits there and writes a PDF Postscript by hand. Someone wrote that document, and revised it, and shared it, and revised it again – and all that sharing, revision, and re-revision would have left copies all over the place.

I am willing to hypothesize for the sake of argument that the Panetta report was developed in a SCIF and all that left was the PDF. That still means there’s a machine with Microsoft Word (or something) in a SCIF with the source of the original document, including all the revisions and changes. If that machine were being used to produce an important 1000-page report, I would bet at least one of my testicles that the reliability of the hard drive on that machine was not assumed; there’s a tape drive, or DVD archives of various versions of that report, in the SCIF. Of course the CIA either: didn’t develop it in a SCIF (my money bet) or they wiped everything in the SCIF as part of a conspiracy to “accidentally” lose the source document. If it wasn’t develioped in a SCIF, then it was on someone’s system, and presumably there are backups of that – unless the CIA is monumentally incompetent about IT – which I am NEARLY prepared to believe. But, still, the author of the report would have taken steps to make sure their 1000-page work didn’t vanish into thin air: it still exists. That person still exists and someone ought to ask them, nicely, what they knew and how they knew it and when.

I have first-hand experience with the issue in a public records context, and second-hand knowledge of how this is handled in certain high-stakes private organizations like major law firms. I *don’t* have any particular knowledge of how things work in classified / national-security contexts. I *imagine* that the principles are similar, but that implementation lags some years behind the “open public sector” in practice, because “not-invented-here” and “our-needs-are-special.”

I have been a non-testifying technical expert on forensics cases, and worked in the Clinton whitehouse when I implemented the whitehouse.gov mail server. I got a long boring briefing about federal records retention policies and there was some discussion as to whether or not public email sent to president@whitehouse.gov was a presidential record (conclusion: it wasn’t) But there’s probably a box with some floppies full of email somewhere in some archive, covered with my chicken-scratch handwriting… I’ve also gotten the retention lecture from various lawyers I’ve worked for and nowadays it’s distressingly close to the presidential records policy and what Colin Powell allegedly advised Hillary Clinton: “Don’t write anything down.” I have always had a problem with that sort of policy because it means “we assume that we may have to lie about what we knew and when, so we don’t want there to be any records.” And that, in a nutshell, is the problem here.

In the national security context I would not assume they are as sophisticated as even private sector lawyers. My experience with data management in those settings is that their security is pathetic, once you get past the front door. Ask Chelsea Manning, Aldrich Ames, and Edward Snowden. By the way, Snowden was a system administrator responsible for … (drum roll) backups. I would say the odds are far better than even that some contractor firm provides business resumption services to CIA; the various “lost” reports are out in a cloud somewhere. It’s plausible that the CIA has no idea where they may actually be. But that doesn’t mean they aren’t out there.

If I had been retained to do a forensic analysis on these reports, you can bet that the backups would be where the meat would be. Just like they were under Reagan during Iran/Contra. Unless the CIA has time-travel; because they didn’t know then that they’d be being investigated now. Or, would be, if the US Government hadn’t decided to bathe in whitewash.

the goal is not data preservation per se; rather, it’s conscious control. We want to define policies about what *is* kept and what *is not,* and to ensure that those decisions are ruthlessly enforced. That is, if we intend to preserve something, it must be preserved; if we do *not* intend to preserve something, every trace of it must be expunged (backups and all)

Yes.

But there would be absolutely no reason why a 1000-page report prepared for the DCI would be stored so as to auto-implode. That beggars belief.

I’m sure there are some projects for which there’s a SCIF and development happens within it, and when the results are complete, it may be an artifact that is the sole surviving copy of, whatever – and then the SCIF is torn down and the drives are shredded, etc. I can believe that. But that doesn’t align at all with what The Guardian describes: a PDF document that has revision-marks in it. In the fantasy scenario above, the output would be a series of bound, numbered reports, with careful access tracking, that lived in a safe. That fantasy scenario would be how if I were asking my staff to prepare me a report on their crimes, except I’d have to go all Lavrenti Beria on them, and lock the documents in a safe, then take them down to the basement room where someone was waiting to put a 9mm in the back of their head.

I’m sure that the CIA wishes they had done that.

There’s another hidden bit to this story (and all similar stories) which always gets overlooked… I first learned of it reading about survivors of the Chilean junta’s (CIA-backed) torture program (sorry, it was many years ago, and I’ve never been able to track the original source down again), but it’s obvious when you think about it: torture is a skill, and like all skills, it requires training and practice to be any good at it. In particular, it’s a skill that carries significant risks when practised badly – you don’t want to accidentally kill a “high value” prisoner because you let an amateur loose on them. There must be a training programme somewhere, and they must be practising on people that not only have no intelligence value, but are clearly known to have to no intelligence value. In Chile, they used homeless people they grabbed off the streets…

Five copies – the SCIF must be backed up too.

Dunc@#10:

Good point. The identities of the torturers are known: they were paid. And probably recruited rather than grown organically (“customer service, unique opportunity” on monster.com)

You’re right about the 5. The next day’s piece in The Guardian discussed how CIA administrators had access to the SCIF – for maintenance purposes.

The data will come out after all the bodies are buried.