It used to be a pretty good rule of thumb that whenever any catastrophe had global consequences, poorer nations would be much harder hit than the richer ones. Hence you would have expected that in many poorer countries, and in the poorest parts of those countries where people live crowded together with inadequate sanitary conditions, the deaths from the pandemic would have skyrocketed. And yet one of the notable features of this pandemic is the reversal of this pattern.

In the March 1, 2021 issue of The New Yorker Siddhartha Mukherjee looked at one particular case of Dharavi, a slum in Mumbai that is the largest in Asia where “a million residents live in shanties, some packed so closely together that they can hear their neighbors’ snores at night. When I visited it a few years ago, open drains were spilling water onto crowded lanes.”

After the pandemic was declared, last March, epidemiologists expected carnage in such areas. If the fatality rate from the “New York wave” of the pandemic were extrapolated, between three thousand and five thousand people would be expected to die in Dharavi. With Joshi’s help, Mumbai’s municipal government set up a field hospital with a couple of hundred beds, and doctors steeled themselves to working in shifts. Yet by mid-fall Dharavi had only a few hundred reported deaths – a tenth of what was expected – and the municipal government announced plans to pack up the field hospital there. By late December, reports of new deaths were infrequent.

I was struck by the contrast with my own hospital, in New York, where nurses and doctors were prepping I.C.U.s for a second wave of the pandemic. In Los Angeles, emergency rooms were filled with stretchers, the corridors crammed with patients straining to breathe, while ambulances carrying patients circled outside hospitals.

Mukherjee says that statistical models predicting deaths worked pretty well for rich countries but were wildly off for the rest of the world.

Nigeria was predicted to have between two hundred thousand and four hundred and eighteen thousand covid-19 deaths; the number reported in 2020 was under thirteen hundred. Ghana, with some thirty million residents, was predicted to see as many as seventy-five thousand deaths; the number reported in 2020 was a little more than three hundred. These numbers will grow as the pandemic continues. As was the case throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa, however, the statistical discrepancy was of two orders of magnitude: even amid the recent surge, the anticipated devastation still hasn’t quite arrived. The field hospital that Fasina had helped set up in Lagos was packed up and shut down.

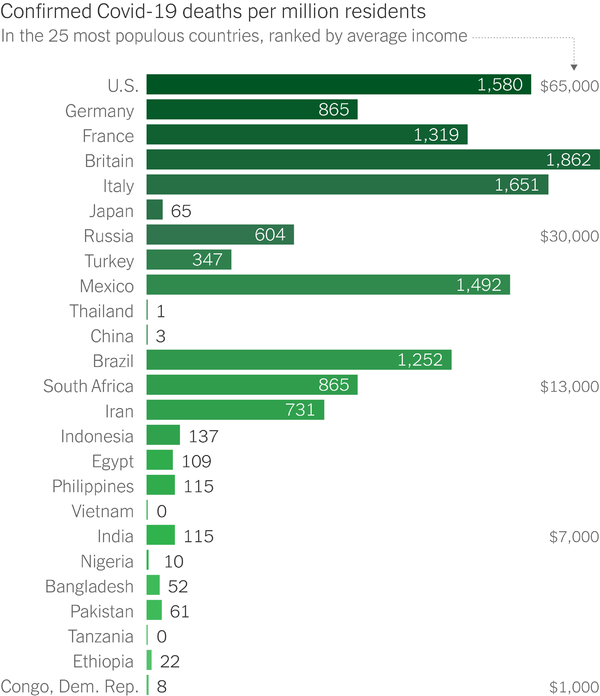

As as can been from this chart prepared by David Leonhardt, a reporter at the New York Times who sends out a daily newsletter, the differences are huge, as much as a thousandfold. We are not in the region where statistical noise could be a factor.

Naturally such widely varying results cry out for explanations but it turns out that there is no single factor that is dominant. One possibility that has been raised is that some countries may have been undercounting covid deaths by assigning them to other causes. While a few may have deliberately done so, that does not seem to be a wide pattern as can be seen from looking at excess mortality rates for the past year compared to previous years. This table of excess deaths per capita does not indicate any serious tilt towards poorer countries. It should be borne in mind that the precautions taken to prevent covid-19 spread resulted in fewer deaths from other contagious diseases like flu.

Leonhardt says that the wide variation is likely due to a multiplicity of factors and lists them. He starts out by ruling out that poorer countries are massively under-reporting covid-19 deaths. Age demographics as a possibility also does not hold up and the main factor.

Covid is usually harder on older people: More than 80 percent of U.S. deaths have occurred among people who are 65 or older.

Across Africa and much of Asia, the population is younger. Birthrates are higher, and other health problems more frequently kill people before they reach old age. In sub-Saharan Africa, only 3 percent of the population is 65 or older. In Pakistan, only 4 percent is. In the U.S., the share is 16 percent, and it’s 20 percent in the European Union.

A related factor may be the fact that nursing homes – where Covid has often spread from one resident to the next – are more common in Western countries. Outside the West, older people often live in multigenerational households.

Still, age does not seem to be the full answer. Statistical models that include age still find unexpectedly low death counts in many poor countries.

Another possible factor is that people in poorer countries are less likely to spend most of their time indoors in poorly ventilated spaces. Their immune systems may also be stronger since they have been exposed to a more diverse array of pathogens.

But also important is that many of the poorer countries acted far more swiftly than the US and other western nations did in taking drastic steps at the beginning of the pandemic.

Rwanda quickly and aggressively enforced social distancing, mask wearing, contact tracing and mass testing. So did several Asian countries. Ghana, Vietnam and other countries restricted entry at their borders. And a consortium of African nations collaborated to distribute medical masks and rapid Covid tests.

“Africa is doing a lot of things right the rest of the world isn’t,” said Gayle Smith, a former Obama administration official.

Again, though, this seems unlikely to be the main explanation for the relatively low Covid death toll. Several Asian and African countries, including India, have had much more scattered policy responses – as the U.S. and Europe have had.

Mukherjee looked at how Rwanda, a very low-income country, dealt with the pandemic in the early days.

Bethany Hedt, a statistician at Harvard Medical School, has worked in Rwanda for the past decade. She noted that in 2020 the low-income country reported only a hundred-some deaths from covid-19, out of a population of thirteen million. “It’s clear to me, at least,” she said, “that it’s because the government had very clear and decisive control measures.” She went on, “When news of covid hit, they imposed a strict curfew, and the Rwandan population really listened. There was limited travel outside the home without documentation. The police would stop you and check. Schools were closed. There were no weddings or funerals. And then, as the numbers decreased, the government played a very good game of whack-a-mole. They have a really strong data center, and anywhere they see an outbreak they do strict control at the local level.”

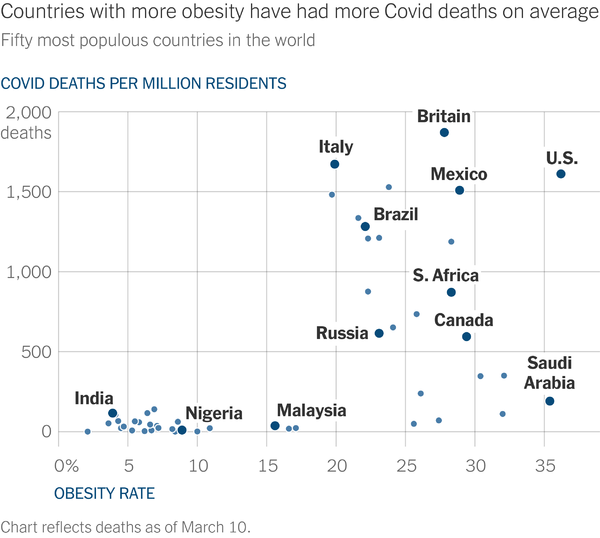

Leonhardt says that another possible explanatory factor that has surfaced is obesity rates, which are much higher in the developed countries.

As Leonhardt writes:

Obesity can cause multiple health problems, including making it harder to breathe, as Dr. David L. Katz told me, and oxygen deprivation has been a common Covid symptom. A paper by Dr. Jennifer Lighter of New York University and other researchers found that obesity increased the risk of hospitalization among Covid patients.

It’s a particularly intriguing possibility because it could help explain why Africa and Asia have suffered fewer deaths than not only high-income countries but also Latin American countries. Latin Americans, like Europeans and U.S. residents, are heavier on average than Africans or Asians.

It is possible that there is a time lag effect and the pandemic storm might hit these countries later but with the vaccines being rolled out, the window for that possibility is closing. In fact, Mukherjee says that there is some evidence that it is not the case that those countries with low death numbers escaped the virus. It is that they are just not seeing the expected number of deaths.

In July and August, the health economist Manoj Mohanan and a team of researchers set out to estimate the number of people who had been infected with the new coronavirus in Karnataka, a state of sixty-four million people in southwest India. Random sampling revealed that seroprevalence – the rate of individuals who test positive for antibodies – was around forty-five per cent, indicating that nearly half the population had been infected at some point. Findings from a government survey last year showed that thirteen per cent of the population was actively infected in September. A large-scale survey in New Delhi, according to a recent government report, found a seroprevalence level of fifty-six per cent, suggesting that about ten million of its residents had been infected.

…In Niger State, which is the largest in Nigeria and is situated in the middle of the country, a seroprevalence study conducted in June found an infection rate of twenty-five per cent, comparable to the worst-hit areas in the United States. Fasina expects that the rate in Lagos and its surroundings will be higher. Nearly a year after Nigeria confirmed its first infections from the new coronavirus, Niger State has reported fewer than twenty deaths. The country’s numbers are climbing – but they’ll need to grow exponentially in order to catch up with the models.

This article looks at the strategies adopted by those countries that were successful in limiting the number of cases and deaths.

Another possible causative factor that has been raised is the degree of willingness in a population to follow rules, defined by something called ‘cultural tightness’ or ‘cultural looseness’.

The results indicated that, compared with nations with high levels of cultural tightness, nations with high levels of cultural looseness are estimated to have had 4.99 times the number of cases (7132 per million vs 1428 per million, respectively) and 8.71 times the number of deaths (183 per million vs 21 per million, respectively), taking into account a number of controls.

…We tested the effect of cultural tightness-looseness on case and death rates per million by October, 2020. Our analyses first controlled for numerous potential factors, such as under-reporting of COVID-19 cases, wealth, inequality, population density, migration, government efficiency, other dimensions of cultural variation such as power distance and collectivism, political authoritarianism, median age, non-pharmaceutical government interventions, and other factors (eg, spatial interdependence, relational mobility, climate, mandated [Bacillus Calmette-Guerin] vaccination, population size, and experience with severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS]).

So what do the researchers mean by cultural ‘looseness’ or tightness’?

To assess cultural tightness-looseness, we used a previously published measure that averages six items, including, for example, “There are many social norms that people are supposed to abide by in this country”, “There are very clear expectations for how people should act in most situations”, “In this country, if someone acts in an inappropriate way, others will strongly disapprove”, and “People in this country almost always comply with social norms”. The measure captures the strength of norms in a nation and the tolerance for people who violate norms.

So it is clear that there is no single clear causal explanation for the variation. The reasons for these huge disparities are going to be heavily researched in order to help us better cope with the next global outbreak of disease.

While it’s important to understand these discrepancies, we should keep in mind that any conclusions may or may not be applicable to the next disease outbreak. That will depend on the specific disease agent and its effects on the body, which may differ significantly from COVID-19.

Wow, you’re really straying from the FtB script today aren’t you? First “women have a right to be safe, but on the other hand…” and now fat-shaming. Didn’t you get the memo that BMI is unimportant, you can be healthy at any size, and implying anything else is oppression? You’re gonna get your SJW card taken off you at this rate.

Oh, also, with reference to the first graph: SUCK IT USA, UK IS NUMBER ONE! We’ve got a leader who is Trump but with a degree he didn’t buy! Hoooorah.

/s

ffs

Trump’s toupee is STILL more ridiculous than Boring Boris’ though! USA! USA!

sonofrojblake,

Those of us from families with a history of diabetes do fair worse if we don’t watch our diets and gain weight. But the idea that it is simply because of moral failing was always too simplistic. I’ve seen a study that after two carb heavy meals our skeletal muscles during recovery from exercise drop energy production by about 60% (I was shocked!) and produce fat instead. Imagine what this does to appetite. Other families may not face this.

I didn’t suggest it was any such thing. It’s no more of a moral failing than, say, declining to have your children vaccinated. It’s a legal choice that people have every right to make if they want, and there are plenty of people a doughnut’s throw from this very blog who’ll defend that right and choice very vigorously. Which is why I was so surprised to see the language of oppression that I quoted, especially in the light of an earlier post.

Others do though. Ignoring the fact quickly generating fat when food was available following shortages might have been advantageous. But now we have to be aware of it.

Crowded, poor populations may already have respiratory viruses circulating, causing substantial immunity to covid.

https://www.bbc.com/news/health-56483445

A major factor not listed is the primary reason it spread: travel and trade. Countries which had a LOT of international travel and tourism were some of the hardest hit -- Italy, Spain, “belt and road” countries like Iran.

Look at Africa, where wealthy South Africa is the worst off, all nearly all the others with massive numbers of cases line the Mediterranean Sea and Indian Ocean. The only exception is Nigeria, a highly educated and wealthy country with many international travellers. Rates in nearly all poorer countries with less international trade are doing better.

Also look at South America, where the seven of the countries with the most international trade all have over 900 deaths per million. Meanwhile Venezuela, ridden with political turmoil and no tourism pre-COVID, has one of the lowest deaths per million in the world (53). The only outlier is Uruguay, but that country is far more progressive socially which likely reflects in people’s willingness to follow rules.

… people in poorer countries … Their immune systems may also be stronger since they have been exposed to a more diverse array of pathogens.

And the (immunologically) weak were culled from the population in infancy and childhood.