While much attention has been placed on the rise in numbers of the religiously unaffiliated and outright disbelievers in a god, Mitchell Stephens looks at a less-publicized aspect and that is that even those who still consider themselves as believers now think of their god in very diminished terms.

He starts with an anecdote about a woman who was asked if she believed in god to which she replied in the affirmative. But when asked the follow-up question of whether she believed in a god who could change the course of events on earth, she replied, “No, just the ordinary one.”

Stephens explains what he thinks is happening.

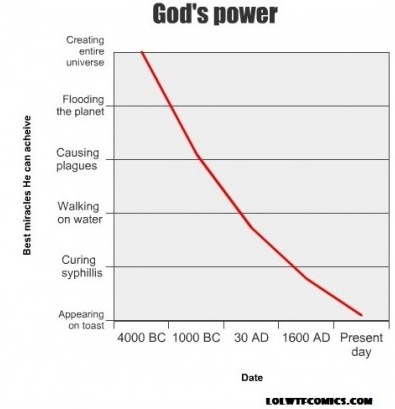

God once was seen as commanding the entire universe and supervising all of its inhabitants — inflicting tragedies, bestowing triumphs, enforcing morality. But now, outside of some lingering loud pockets of orthodoxy, we have witnessed the arrival of a less mighty, increasingly inconsequential version of God.

…In 1820, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, himself a committed atheist, predicted that religion would not be “o’erthrown” but simply become “unregarded.” Despite all the noise and news made in recent decades by beleaguered adherents of one or another supernaturally inspired orthodoxy, that is the direction in which we are headed.

Religion’s supporters can take comfort in the fact that, so far, most minds still find room for some sort of God. But as religion recedes and we contend less and less with the strictures of ancient holy texts, it is an increasingly distant, indistinct, uninvolved, ordinary God.

It is undoubtedly true, as this cartoon indicates, that over time people have been steadily decreasing their expectations of what the god they profess to believe in can do or is willing to do.

This is the problem with the word ‘god’. People can interpret it as meaning practically anything they want it to mean. So maybe surveys should ask the more pointed questions such as whether they believe in a god who can change the course of events, rather than just about god.

It used to be that “god of the gaps” was theists claiming that science couldn’t account for everything.

Now, “god of the gaps” means their “god” is falling through them.

…we have witnessed the arrival of a less mighty, increasingly inconsequential version of God.

I think “return” is a better word than “arrival.” The Pentateuch clearly describes a deity that may not be quite inconsequential, but nonetheless limited in its abilities and subject to the same emotional failings as mortal humans.

I love the graph! I saw god in my cappuccino this morning…he tasted so good!

Good afternoon Mano,

Many years ago, as a graduate student, I took a course with Rabbi Roger Klein and one the texts we examined was Jack Miles’ God, A Biography.

Miles, a former Jesuit, made the case that the precise order of books in the Hebrew Scriptures--which is different from the order of books in what Christians mistakenly refer to as the “Old Testament”--was intended to show just the same curve as in the graph you show above.

The book is fascinating and I commend it to anyone who wishes to understand something of the psychology of religions.

Do all you can to make today a good day,

Jeff Hess

Have Coffee Will Write

On the other side of the story there is, IMHO, reason to believe that as supernatural powers recede the estimation of normal, workaday, humans might increase. It shakes out like this: Suppose there are orphans trapped in a burning building and

A) A supernatural being shows up and rescues the orphans.

B) Some normal human shows up and rescues the orphans.

Note that the supernatural being doesn’t break a sweat. A snap of the fingers, or tentacles and the orphans are safe. In fact you might criticize the being, seeing as that such beings are defined as being all knowing and all powerful. They should have known of the fire beforehand. So why did they wait for the orphans to be under threat. In any case our supernatural being can’t be hurt or killed so they risk nothing.

In the case of the normal, fallible, human being we are talking about someone who has a perfect excuse for any failure. She is only human. When she runs into the burning building she is risking her health and life.

Humans are really amazing. Given limited understanding, resources, and power most humans still try to do the right thing.

I don’t think I can quite agree with Chiroptera, though it’s an interesting argument. The “G-d” of the Torah certainly was less powerful, but I see that character as being on the opposite end of a spectrum with the “inconsequential God”, with the omnipotent omniscient omnibenevolent bearded man being in between the two. The OT God was less than omnipotent precisely because he was so intimately involved with the day-to-day workings of the world that it would have made a wildly implausible story if he could do anything. This was a god who was right there in the trenches, and thus had to be limited in his superpowers. The NT God is somewhat more removed, and therefore we can talk about unlimited power and wave away the obvious contradiction with this “mysterious ways” garbage (an excuse that would have failed to convince even the most credulous believer in a god as deeply involved with everyday existence as Moses’ pal). The modern inconsequential god, on the other hand, is so far removed that superpowers become superfluous. This is a god that is more of a general happy feeling, a vague sense of meaning-without-someone-to-do-the-meaning.

They are similar in their lack of omnipotency, but very different in the reasons for it.