Our know-nothing president has wondered why we haven’t stopped hurricanes by dropping a nuke on them. Why he thinks that would work is a mystery. Hurricanes are energetic phenomena (the heat release of a hurricane is equivalent to a 10-megaton nuclear bomb exploding every 20 minutes), so adding more energy, even if it is a relatively small amount compared to the total energy of the storm, doesn’t make sense.

That hasn’t stopped his sycophants at Fox News from cheerleading the idea.

“You’re going to say this is crazy,” Kilmeade said. “But I always thought, is there anything we can do stop a hurricane?”

“I don’t think an atomic bomb is the way to do it,” co-host Steve Doocy noted.

“Okay, maybe that wouldn’t have been my first option,” Kilmeade opined. “But I always think about that. With all the progress we’re making with driverless cars and Instagram, could we possibly stop a hurricane?”

I thought Doocy was the stupid one, but I guess they take turns. Somebody tell me what the connection is between driverless cars, Instagram, and stopping hurricanes with nuclear explosions, because I don’t see it. I guess some people just see technology as one big mish-mash that inevitably leads to solutions for every problem they have. Hey, they can make electric can openers, so why can’t they cure cancer?

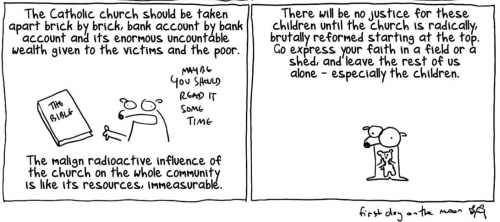

They should think more about the unintended consequences, too. Nuke the hurricanes, and you’ll just make the spiders mad and radioactive.

Meanwhile, Elon Musk had some more brain diarrhea and has decided we ought to nuke Mars. His idea is that because Mars is too far away from the sun, we provide it with miniature suns, close up and personal, with lots of bombs going off above its atmosphere.

“Nuke Mars refers to a continuous stream of very low fallout nuclear fusion explosions above the atmosphere to create artificial suns. Much like our sun, this would not cause Mars to become radioactive,” the entrepreneur [is “entrepreneur” a synonym for “loon” now?] tweeted yesterday (Aug. 20).

“Not risky imo & can be adjusted/improved real-time. Essentially need to figure out most effective way to convert mass to energy, as Mars is slightly too far from this solar system’s fusion reactor (the sun),” he added in another tweet, responding to someone who asked about the risks associated with this terraforming plan.

Remember that figure, that an Earthly hurricane is pumping out the equivalent of 10 megatons of energy every 20 minutes? That’s how much energy is in an atmosphere. He’s got a vague notion of that — he says he wants to send a “continuous stream” of nukes to Mars — but he hasn’t thought about the cost or any of the consequences. Furthermore, imagine that he manages to divert a substantial fraction of the world’s economy to this radically expensive plan (funny how the primary objection from Republicans to mitigating climate change on Earth is that it would be too expensive and wreck our economy, while this guy is scheming to wreck the world’s economy by warming an uninhabited planet) and actually raises the temperature of Mars a degree or two. Then what? It’s a dead world, it’s going to take more than a slight temperature rise to make it habitable, and good luck convincing colonists to move to the desert you’ve been nuking for decades.

I’m only going to tentatively favor this plan if it also involves seeding Mars with angry, radioactive spiders.

It’s not going to happen, it’s not going to work if it did happen, and all this is is a desperate ploy by Elon Musk to a) get attention, and b) sell stupid t-shirts.