We’ve recently been treated to a round of Sokal-style hoax papers that were declared to invalidate (or at least severely damage) parts of a field, because they were accepted by publications within that field. [pharyngula]

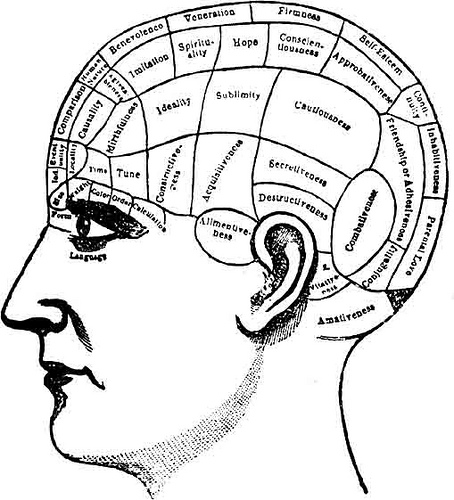

PZ asks “So…when creationists sneak bad papers into legit journals, does evolution collapse?” and then, in another posting observes, “History will judge evolutionary psychology as the phrenology of our era.” [pharyngula] I happen to agree with PZ’s views as expressed in both of those postings but there’s a deeper question embedded in the discussion: at what point can we say that a field of study or a branch of research has been discredited? At what point should we say “stick a fork in it, it’s done?”

Here’s how I see it: we assess a field as a whole based on its founding principles and their accuracy. By accuracy, we mean the panoply of science: experiment and observation should reveal a cause/effect relationship that can be measured and (ideally) manipulated with predictable results. If the founding principles are slightly wrong they can be adjusted – as long as those adjustments work within science: otherwise, how would we know they were “wrong” in the first place? So, for example, Darwin did not get everything completely 100% right (as creationists are fond of harping about) but that’s why today we study the “Neo-Darwinian Synthesis” which is a branch of science that has evolved from Darwin’s original theories based on further observation, experiment, and discovery.

From that view, an article accepted in a journal that focuses on a particular field, cannot discredit the entire field unless the article somehow demolishes one of the founding principles of the field. Sokal-style hoaxes, in other words, may say something about the quality of a particular journal, or its review process, but the only way to discredit an entire field is to attack its founding principles, not to show that its journalists are prone to error.

Look at an easy example: phrenotherapy. Let’s suppose we have a science called “phrenotherapy,” built on the founding principles of the science of phrenology – to adjust a person’s attitude and abilities, we whack their skulls with various amounts of force, or we bind them up with stereotaxic trusses that push or tug on carefully selected regions of the head. The resulting changes of shape to the head affect the phrenology of the subject, thereby – according to long accepted theory – modifying their attitudes and abilities. The senior phrenotherapists’ symbol, the sterling silver mallet of loving correction, is a badge of distinction in the field. There are two paths to discrediting phrenotherapy:

- attack its founding principles

- demonstrate piece by piece that its practices are ineffective, its theories of operation do not withstand study, and that its practices lack predictive power or repeatability

In order to attack phrenotherapy’s founding principles, we’d have to attack phrenology’s founding principles – what is the mechanism of action whereby bumps and dents on the head produce behaviors? We’d also probably want to observe that phrenology’s predictions are not better than random plus or minus placebo effect, etc.

This is where we find ourselves in a land war in Asia: with “modalities” like acupuncture or homeopathy, they keep coming up with plausible-sounding results (because they don’t understand that they need to measure efficacy against the placebo effect, not a control that experiences no intervention at all) – and it’s:

I get knocked down, but I get up again

You are never gonna keep me down

I get knocked down, but I get up again

You are never gonna keep me down

I get knocked down, but I get up again

You are never gonna keep me down

I get knocked down, but I get up again

You are never gonna keep me down

In the case of some “modalities” the practitioners come up with a circular self-justifying theory: acupuncturists have their “chi” maps, and chiropractors their “subluxations” and homeopaths’ water has memory. These are subconscious or blatantly dishonest attempts to shore up their founding principles – and the more sciencey and complicated they seem, the better, because (the practitioners insist) you cannot simply dismiss the field out of hand because chi! or subluxations! Of course we actually can (and should) not focus on the individual findings, but should keep our main axis of attack on the evidence for the truth of the founding principles.

If the phrenotherapist says “yeah, but it works!” our response should be “phrenology hasn’t proved its case, so you’re wrong to be engaging in interventions based on something that is unknown.” It is not the “genetic fallacy” to attack the foundation of a system of knowledge as an indirect attack on systems that depend on it. The poorly-named “genetic fallacy” would be if you said “phrenotherapy is wrong because it was invented by Marcus Ranum, who says he made it up as a drunken joke one day.” Challenging the constructive basis of knowledge is epistemology 101: how do you know X. In the case of phrenotherapy it purports to ‘know’ that whacking certain places will have certain effects – that’s the epistemological claim. Well, how do we know that?

I’ve been picking on an easy straw-filled modality for this example, but the question of founding principles and how to dismiss an entire field applies, as well, to some pretty ‘sciency’ stuff that has been taken fairly seriously. For example: PSI research. A great deal of money has been spent doing flawed experiments on PSI, when a more effective attack on the entire field would have been to ask what the operating principles of PSI might be, and how to gain knowledge about those. There exists a certain amount of leeway in science for detecting or measuring a known effect of an unknown cause (e.g.: dark matter, the known effect being gravity) which places other fundamental theories in opposition. For example, for PSI “remote viewing” to work we’d probably have to shelve or amend a bunch of conservation laws and general relativity.

That all brings me back to the question of “how do you dismiss an entire field?” Like, for example, gender studies. The way to do that would not be to attack its tentacles (the various journals) but, rather, to strike it its head: demonstrate that the principles on which it is built are flawed. I think gender studies is safe from such attack, since its founding principles are based on a philosophical argument regarding equality. In other words, there are some fields that may be dismissed entirely, and gender studies looks like it isn’t one.

Evolutionary psychology’s trickier. The foundational principles of evolutionary psychology appear to be obviously true:

- we have evolved

- we behave

- our behaviors (as part of us) depend on our evolution, to some degree (i.e.: you can’t sing unless you’re equipped by evolution to do so, and we experience psychological effects related to singing)

I’ll argue that evolutionary psychology can’t be dismissed entirely because, according to 3) above, there has to be some truth to it. And that puts us in a “land war in Asia” scenario where we have to grapple with each result and challenge to what degree it’s supported by the founding principles. The challenge for evolutionary psychologists ought to be to argue the degree to which behaviors depend on our evolution, because everything past that is secondary. Like the phrenotherapists, they’ve put the cart before the horse and have started making conclusions based on an unknown: the degree to which our behaviors are learned versus evolved is unknown and all of evolutionary psychology depends on that unknown.

This is all a roundabout way of explaining why I rejected religion early on. The basic principles of religions contradict reality as it appears to be. Never mind all the other stuff that can get layered on top of that, let’s go back and sort out a theory of ensoulment that squares with physics as we understand it today, then run some tests to show that the theory of ensoulment doesn’t contradict anything and there’s something there, and then we can talk. In the meantime, souls – a founding principle of most religions – are in doubt, and everything that depends on ensoulment is, too.

It ought to be pretty obvious where “falsifiability” fits into my scenario: Popper’s idea was to require that the truth or falsity of a proposition’s foundational principles ought to be determinable, somehow. Otherwise, we have things like religions and alt-med “modalities” that lean on unverifiable things, which means they have protected their basic principles from attack. If that appears to be deliberate, that’s a red flag. As you can see from the example of gender studies, though, I believe there are ways that a field can avoid being dismissed because its founding principles are based on solid philosophical arguments.

Eugenics is an example of a “science” that we have managed to completely dismiss. Coincidentally, the arguments for eugenics are the same as the arguments for evolutionary psychology. That’s why I feel that evolutionary psychology is going to continue to be twisting in the wind until they nail down their founding principles – I expect that’s going to be hellish, since behavior appears to be a fractally complicated mass of “it depends.”

“Convergence falsifies Evolution” [fierce roller] the founding principles of evolution are variation and differential survival and reproductive success over time. Good luck anyone falsifying that!

Speaking of phrenology, this is a weird piece of “oh, Japan, no.” reported at The Daily Beast [beast] The Japanese are apparently prejudiced against certain blood types on the assumption that blood type influences behavior:

The Japanese term for this is “blood harassment” or “burahara” when abbreviated.

Japan’s fascination with blood types began with the published, and flawed, research of psychologist Takeji Furukawa. He published a paper in 1927, “The Study of Temperament Through Blood Type,” which was influenced by research in Europe that aimed to prove arguments for racial superiority.

Hm.

I’ve been pondering something like “Is the fundamental principle completely bullshit?” But that’s more for things like homeopathy and astrology.

«Why should anyone have ever believed that like cures like? Why should anyone have ever believed that “as above, so below”? Is there actually anything at all that would even suggest that these principles are not completely imaginary?»

And so on.

Owlmirror@#1:

“Is the fundamental principle completely bullshit?”

I was trying to make it positive, because if we say we want things to be “not bullshit” then we have to argue that some things “are bullshit.” It seems to me wiser to say “it’s left as an exercise to the proposer to demonstrate that their principles aren’t bullshit” before we even bother having a discussion about them.

That would neatly dispatch a lot of things on grounds of founding principles:

acupuncture: show us your chi or go home

chiropractic: show us a “subluxation”

homeopathy: explain how this works, given the dilutions you’re talking about

evolutionary psychology: explain clearly how you know the behavior is evolved and not learned

etc.

Owlmirror @1:

Mithridatism has been around for ages. For some, it might have at least hinted at the possibility.

Owlmirror, #1

In the case of astrology it’s very easy. In many cases the movements of the heavens do have obvious, regular effects on the world we see around us. The changing of the seasons, the tides, and all the rhythms of weather patterns and the biological world that depend on those. To suspect that there are other, deeper and subtler, connections as well is not an utterly ridiculous hypothesis.

Astrology is an interesting case though. For most of its history it encompassed everything we would understand as astronomy, and so in a very real sense it is not a discredited field and its foundational principles haven’t been demolished – we just use another of its ancient names and make distinctions between two of its activities that most of its practitioners never did. Even the notion that the movements of the heavens have effects here on earth is not entirely wrong – it’s just that those effects are significantly less complex than we had imagined.

In a similar vein, the science of the soul (psyche) isn’t a discredited field either. Psycho-logia is still studied in universities around the world, it’s just that modern conceptions of the soul are rather different from (most) medieval and ancient ones. We still believe that there are special, investigable properties that distinguish living beings from non-living ones. We still believe that there can be a rational understanding of the workings of human thought. That neoplatonic and Christian ideas about immortal souls as a locus of eschatological merit are no longer in vogue doesn’t mean the whole enterprise is busted, just as the lack of Hippocritean humour theory in modern medicine doesn’t scotch that.

With regard to Evolutionary Psychology, I’d expect or at least like and hope to see something similar happening as cartomancer describes with Astronomy/Astrology. As you said in the opening post, there has to be some truth to EP and it’s foundations are difficult to attack.

If the field managed to gradually shed those researchers who like to gather their preconceptions in a bundle and take them for a walk, it might gain more (deserved) respectability. More importantly, there could be interesting contributions. For example something among the lines of what behaviours actually are related in part on our evolutionary history and to what extent they are reshaped by our society and environment. Figuring something like that out and actually proving it would probably a life’s work.

3a. Instinct.

3b. Volition.

Sapients we, sometimes we can over-ride them — at least in the short term.

Um, perhaps too terse in my previous.

3a is fairly the province of EV, but 3b is more anthropology and sociology and cognitive psychology.

When I started reading this, I wondered whether “phrenotherapy” is something you came up with, or did you just take it from some history book. It reminded me of these “therapies” doctors used about hundred years ago.

And the worst thing is that plenty of modern practices aren’t much better. In university I had a classmate who was a fan of some acupuncture derivative and regularly had her back covered in bruises. Ouch. Not to mention drinking poisons to cure your cancer. Another example: drugging children who are simply energetic and don’t like sitting still (ADHD).

I rejected God when I was six years old based on experimental evidence. I had been told that there is a God living in the sky and that he answers to prayers by intervening and making miracles. One day my mum was taking me to the dentist. I didn’t fancy having my teeth drilled, so I prayed to God: “Dear God, please make the dentist sick so that when we arrive to the clinic, she isn’t there.” My prayer wasn’t answered, I had my teeth fixed, I concluded that prayers do not work, and that was the last time I prayed to God. Amusingly, I stopped believing in God at the exact same age as I stopped believing in Santa Claus.

Ieva Skrebele@#8:

I wondered whether “phrenotherapy” is something you came up with, or did you just take it from some history book

I made it up. I was going to do a phrenotherapist cosplay a few years ago (basically steampunk with a big mallet and a stereotaxic sort of rig…) But it never happened. Something like the doctor in Brazil…

Not to mention drinking poisons to cure your cancer.

Some of those poisons work, though. That’s the thing: there is solid evidence that they can increase survival times with certain cancers, and even drive them into remission. My sister has been living with a “fatal” lung cancer for 10+ years thanks to some of those poisons – and when I was a kid she’d have had about 9 months.

drugging children who are simply energetic and don’t like sitting still (ADHD).

That’s another problem. Psychology has an epistemological problem regarding what constitutes a “disorder” and it’s probably the case that some people are being prescribed drugs that shouldn’t. On the other hand, some people are being prescribed drugs that are saving their lives. It’s complicated, to say the least. I think the only rational thing to do is to measure outcomes: is it helping people’s lives? In many cases, definitely. I’m skeptical of some of it, though.

Amusingly, I stopped believing in God at the exact same age as I stopped believing in Santa Claus.

… and usually there’s much more evidence for Santa Claus.

John Morales@#6 & #7:

3a is fairly the province of EV, but 3b is more anthropology and sociology and cognitive psychology.

AKA “nature” and “nurture” (environment)

I think evolutionary psychology is going to continue to be a train-wreck because there’s no evidence where individual behaviors fall on that spectrum. And why should we assume that there’s a single knob that applies to all behaviors?

Consider “dancing” as a “skill” (whatever those are!): an EP might say that we have an evolved in predisposition to rhythm, like birds and other animals, so that’s going to affect our performance. And we have evolved variances in musculature. And we may (?do we know?) have evolved variances in neuromotor precision (I just made that term up) So an EP could say fairly that “dancing is impacted by evolution!” but “dancing” is a vague concept – are we talking about swing dancing or medieval pavanes? One stresses timing and motion, the other is timing and memory and is a much less difficult task for most people. You can start deconstructing “skills” (whatever they are!) down into sub-elements: basketball is neuromotor precision, strategic thinking (whatever that is!) and rhythm, etc. So if evolution affects our basketball playing it’s going to affect our dancing differently though similarly. And, of course, nobody evolved with a built-in predisposition for swing dancing because it’s a fairly new thing.

That’s an imprecise sketch of how I see the problem, but I think it works: it’s not one “knob” it’s a potentially huge number and some of them synergize and others superceed. EP has to tease apart the knobs and their relationships. Good luck with that!

I will say in defense of some EP, there are some skills that do appear to be genetically linked. There was a cool study I read about twins performing similarly on Dance/Dance Revolution games (based on genetic relatedness, homo-/hetero- raised separately) Of course I am appropriately skeptical about twin studies and p-hacking in general. I’m not a “blank slate” proponent, nor am I a genetic determinist: I think the whole thing is a gigantic cluster of confusion, just like brain anatomy and cognition. My bet is that in the long run it’s going to be a problem akin to figuring out ‘why’ a neural network does what it does: absurdly and even pointlessly difficult (since the inputs are what predict the outputs and the inputs are deterministic but incomprehensibly complex)

PS – I tried to find the DDR study but cannot. I wonder if it was withdrawn.

Some of those poisons work, though.

Well, yes, some medicines and therapies, which are scientifically proven to work, also have some really nasty side effects, so technically they could be labeled as “poisons”.

But that is not what I had in mind. I was thinking about all this stuff advertised by “alternative” medicine crowd. For example, laetrile, found naturally in the pits of apricots and various other fruits. Or the “Grape Cure,” which consists of consuming nothing but grapes or grape juice. Well, technically grapes are not bad for you, however eating nothing but a single food is going to result in nutrient deficiencies. And a serious nutrient deficiency can kill you faster than most cancers. Or corrosive salves, which are marketed for skin cancers with the claim that they “draw out” the cancer.

I often find that people believe in God or in alternative medicine not because they are too stupid to understand the evidence and reasoning, but because they desperately want to believe and therefore choose to ignore the evidence. As one of my religious acquaintances put it, “A person of faith is never alone in life regardless of what hardships they face, and God gives their life a meaning.” Also, alternative medicine promises cures whenever real medicine is powerless. You don’t have any alternative dental fillings, because traditional dentists do a pretty good job and can fix problems. You have alternative cancer treatments, because real doctors often simply cannot cure some types of cancers. Despair is what makes people believe in nonsense and ignore facts.

That’s another problem. Psychology has an epistemological problem regarding what constitutes a “disorder”.

Well, usually they just claim that whatever the majority is doing is normal, and anything that differs from the “norm” is a disorder. That’s how we ended with the claim that if somebody happened to be born with a female body, but prefers to buy their clothes in the men’s department, then this person is “sick”.

I think the only rational thing to do is to measure outcomes: is it helping people’s lives?

Yes, I agree. But you still have to be careful here. Is the treatment really improving the life of a patient, or is it simply making them more “normal”, thus the quality of their life improves simply because others stop discriminating them. In the second scenario the fault is not with the person who is “abnormal”, but with the society, which demands that “everybody must be normal” and “it is ok to discriminate ‘abnormal’ people”. For example, when a queer person or somebody with autism spectrum receives “therapy”, which teaches them to act and imitate normal behaviors, the result is likely to be measurably less discrimination, which could be claimed as improved life quality.

Men At Arms, by Sir Terry Pratchett, describes the practice of retrophrenology thus:

Great minds, etc.

@Marcus Ranum #2:

What I am trying to articulate is that there is — or should be — a distinction between things that are unknown, but not completely implausible, versus things that are unknown but implausible. Consider medicine: There are a lot of medications where the mechanism by which they work is unknown, and there are confounding factors in the placebo and nocebo effects, and the natural ability of the body to repair itself (which is why we have double-blinded tests that look for statistical significance).

Yet if we hear of something like psychic surgery, I think we can take a stronger stance than “well, these guys just need to pass a double-blinded test to show they’re doing something”. I think we can say that it sounds like completely fraudulent bullshit on its face, and that there is at least some justification in dismissing it out of hand.

I think a possible summary might be something like: It’s not just that there is no evidence for {astrology, homeopathy, psychic surgery}, but rather, the evidence that we do have of how the world works contradicts the fundamental thesis of the claims.

Of course, I suspect that the above needs more work.

[I think this may tie in to the analysis and definition of “paranormal” and “supernatural” that I stopped arguing about but have not stopped thinking about. Would you really argue that astrology and homeopathy, in their fundamental claims about how reality works, are no different than bad science that doesn’t make claims that are extraordinary in principle, like Wakefield’s retracted vaccination-autism paper, frex?]

[I may be misremembering your position, but I think when were discussing the definition of “paranormal”, you did seem to be coming down on the side of declaring that some phenomena were sufficiently outside of how reality is known to work to be declared bullshit. You used an example from fiction: If Garion creates a flower, and does it again and again in laboratory conditions, stripped naked in a room full of sensors, he fills the room with flowers: the most we can say is “Garion appears to be able to create flowers by some unknown process. Probably a trick.” ← That last part looks pretty close to a declaration of “probably bullshit” to me.]

Now, evo-psych doesn’t have a fundamentally implausible principle, but rather, seems to have severe problems with sloppy methodology and post-hoc rationalizations that suffer from severe bias (and figuring out where the biases are requires some critical thinking).

A quote that I remember seeing from David Marjanović: “The closer you get to humans, the worse the science gets.” People have biases in studying/thinking about people which makes studies of people susceptible to sloppy thinking.

sonofrojblake@#12:

Great minds, etc.

I need to read more of him. I read the first discworld book and it felt too much like Piers Anthony’s glib 80s nonsense so I put it down and never picked it back up.

It’s possible I absorbed that idea from someone talking about it, I don’t know. Ideas are like that. In the future, I’ll reference Pratchett because he’s more authoritative!

Owlmirror@#13:

there is — or should be — a distinction between things that are unknown, but not completely implausible, versus things that are unknown but implausible

Yes! That’s a great way to put it.

It seems to come down to the problem of epistemology: sooner or later someone challenges you to try to prove a negative. I am comfortable saying “for you to see a ghost, everything we know about conservation laws in physics would have to be wrong” which, to me, amounts to saying “ghosts are impossible.” But that doesn’t do it for some people.

the evidence that we do have of how the world works contradicts the fundamental thesis of the claims

Yes. That’s as close to “that’s impossible” as I am willing to go. I suppose it could be there’s something – but I’m not going to reject all of our current understanding about how this simulation works, in order to accept a dodgy premise.

you did seem to be coming down on the side of declaring that some phenomena were sufficiently outside of how reality is known to work to be declared bullshit

Yes. I like the example of ghosts. For you to “see” a ghost it’s got to be ‘real’ because our definition of ‘reality’ is that real things interact with light so that our eyes can see them. There are a lot of important principles embedded in the idea of vision that contradict the usual assumption about “ghosts” being immaterial, etc. (most usually “ghosts” appear to be second-order effects of unspecified causes, i.e.: something made the temperature drop and caused fog. oh? what was that?)

Now, evo-psych doesn’t have a fundamentally implausible principle, but rather, seems to have severe problems with sloppy methodology and post-hoc rationalizations that suffer from severe bias

I would be willing to slide a few feet out on this particular limb and say that I think most evo-psych is an effect of bias confirming the experimenter’s expectations.