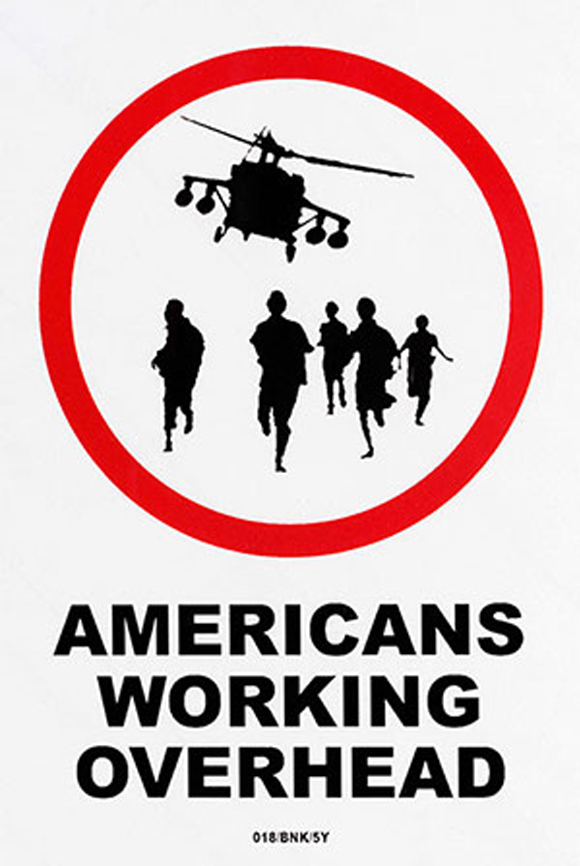

I keep loose tabs on what’s going on regarding the US’ “no boots on the ground” deployment in Syria. And, frankly, it’s really hard to tell: the US media is suspiciously quiet about it (I assume they have been told to shut up) – when I go to outside sources, it gets confusing, fast. The overall impression I come away with is that Turkey is shooting at everyone, the US Air Force has a terrorist organization (the PKK – Kurdistan Worker’s Party, a leftist revolutionary group listed as a terrorist organization by NATO and the US) directing air strikes, and ISIS is cropping up in places that the media hasn’t been talking about.

For starters, I was surprised to discover that ISIS posted video of beheading two victims in Egyptian Sinai [int] I thought, “What? Wait? Egypt?” because, unlike our president, I actually know something about the geography of the Middle East. So, ISIL is operating on the other side of Israel, Jordan and Saudi Arabia – across the Red Sea. Why is this important? It’s not, tactically, but it illustrates that the war going on in the greater Middle East doesn’t have ‘battle lines’ or a ‘front’ – the areas being contested are large, ISIS can blend into the civilian population when it wants to, and there is enough mobility in the region that insurgents can duck across a border here and there, and recoup and refit, or rebuild their command and control.

For starters, I was surprised to discover that ISIS posted video of beheading two victims in Egyptian Sinai [int] I thought, “What? Wait? Egypt?” because, unlike our president, I actually know something about the geography of the Middle East. So, ISIL is operating on the other side of Israel, Jordan and Saudi Arabia – across the Red Sea. Why is this important? It’s not, tactically, but it illustrates that the war going on in the greater Middle East doesn’t have ‘battle lines’ or a ‘front’ – the areas being contested are large, ISIS can blend into the civilian population when it wants to, and there is enough mobility in the region that insurgents can duck across a border here and there, and recoup and refit, or rebuild their command and control.

I’m not mentally trapped in the WWI and WWII mindset of a meat-grinder “front line” or “forward edge of battle area” – but I worry that the strategists that are running the war against ISIS are. The thin messages we get in the US news, about the re-taking of Mosul or the attack on Raqqa, those are rooted in military ideas from the dawn of time: take your enemy’s capital and you win. Unless you’re Napoleon and you take Moscow and discover the Russians let the winter do their fighting for them, or you’re the US in Vietnam and you discover that your enemy is used to operating under an occupying force and you can “take” the whole country and hold none of it. (Hint, British: Kut, Kandahar)

That’s what worries me about the ISIS in Egypt thing: it indicates (what we already should know) that ISIS has support all over the Middle East, and can and will move and pop up where it does. Historically, the US’ only response to that sort of warfare is to switch over to area bombing – a technique that creates much more hostility than it destroys. How much do you have to bomb people to get them on your side?

The next bit of news appears to show that the US’ attempt to interpose troops [stderr] between the Turks and the Kurds (and ISIS and the Syrian Government, too!) hasn’t worked. That, too, should have been obvious, since the fighting is taking place where there are no front lines and the forces involved are irregular, and mobile.

According to The Turkish General Staff, the clashes with the militants also saw 11 fighters from Syrian opposition forces also injured.

Turkish military source also said 100 ISIL and 4 PKK/PYD targets were destroyed, including Islamist extremist shelters, defensive positions and command-and-control centers. [int]

So, Turkey is basically fighting Hobbes’ war of “all against all” – they are attacking ISIS, PKK, and Syrian opposition forces (I am not sure if that’s Syrian Government, or Syrian rebels) – remember, the US troops were thrown in as human shields to keep the Turks from attacking PKK holding Manbij. The Kurds are trying to set up a nation, and the Turks are trying to prevent that, as they have been trying to prevent it for a very long time. When the British divided up the Ottoman Empire, I wish they had carved out a Kurdistan for the Kurds, and (why not?) an Israel, too, and been done with it. That way they’d be the bad guys forever, which they probably deserve to be.

So, Turkey is basically fighting Hobbes’ war of “all against all” – they are attacking ISIS, PKK, and Syrian opposition forces (I am not sure if that’s Syrian Government, or Syrian rebels) – remember, the US troops were thrown in as human shields to keep the Turks from attacking PKK holding Manbij. The Kurds are trying to set up a nation, and the Turks are trying to prevent that, as they have been trying to prevent it for a very long time. When the British divided up the Ottoman Empire, I wish they had carved out a Kurdistan for the Kurds, and (why not?) an Israel, too, and been done with it. That way they’d be the bad guys forever, which they probably deserve to be.

The situation remains a dangerous multi-way quagmire, with a great potential for flare up into greater conflict. The US’ policy of staying uninvolved while flinging high explosive around – that’s not working. It’s protecting American lives, but the entire mission doesn’t make sense at all: the fighting in Mosul is showing, like when the US Marines destroyed Najaf in 2004, that you can destroy a town, take it over, and still not hold it. The US learned that in Vietnam, too, but the institutional memory of its military is very short.

The other day I mentioned some bits in Halberstam’s The Best and the Brightest.[amazon] (Now on my recommended books list!) Stop me if any of this sounds familiar to you:

The Kennedy commitment changed things in other ways as well. While the President had the illusion that he had held off the military, the reality was that he had let them in. They now began to dominate the official reporting, so that the dispatches which came into Washington were colored through their eyes. Now they were players, men who had a seat at the poker table; they would now, on any potential dovish move, have to be dealt with. He had activated them, and yet at the same time had given them so precious little that they could always tell their friends that they had never been allowed to do what they really wanted. Dealing with the military, once their foot was in the door, both Kennedy and Johnson would learn, was an awesome thing. The failure of their estimates along the way, point by point, meant nothing. It did not follow, as one would expect, that their credibility was diminished and that there was now less pressure from them, but the reverse. It meant that there would be an inexorable pressure for more – more men, more hardware, more targets – and that with the military, short of nuclear weapons – the due bills went only one way, civilian to military. Thus one of the lessons for civilians who thought they could run small wars with great control was that to harness the military, you had to harness them completely; that once in, even partially, everything began to work in their favor. Once activated, even in a small way at first, they would soon dominate the play. Their particular power with the Hill and with hawkish journalists, their stronger hold on patriotic-machismo arguments (in decision-making they proposed the manhood positions, their opponents the softer, or sissy positions), their particular certitude, made them far more powerful players than men raising doubts. the illusion would always be of civilian control; the reality would be of a relentlessly growing military domination of policy, intelligence aims, objectives and means, with the civilians, the very ones who thought they could control the military (and who were often in private quite contemptuous of the military mind), conceding step by step without even knowing they were losing.

The immediate result of the Kennedy decision in Devember to send a major advisory and support team to Vietnam was the activation of a new player, a major military player, to run a major American command in Saigon. At first, when Kennedy took office, the pressure had come only from Diem; then, because of his policy to reassure Diem and make him the instrument of our policy, Kennedy had sent over Fritz Nolting, who would soon seem to many to be more Diem’s envoy to the United States than vice versa. Now, by appointing Lieutenant General Paul D. Harkins to a new command, Kennedy was sending one more potential player against him, a figure who would represent the primacy of Saigon and the war, as opposed to the primacy of the Kennedy Administration, thus one more major bureaucratic player who might not respond to the same pressures Kennedy was responding to, thereby feeding a separate and potentially hostile bureaucratic organism.

Harkins began by corrupting the intelligence reports coming in. Up until 1961 they had been reasonably accurate, clear, unclouded by bureaucratic ambition; they had reflected the ambivalence of the American commitment to Diem, and the Diem flaws had been apparent both in CIA and, to a slightly lesser degree, in State reporting. Nolting would change State’s reporting and to that would now be added the military reporting, forceful, detailed, and highly erroneous, representing the new commander’s belief that his orders were to make sure things looked well on the surface. In turn the Kennedy administration would waste precious energies debating whether or not the war was being won, wasting time trying to determine the factual basis on which the decisions were being made, because in effect the Administration had created a situation where it lied to itself.

I mention Najaf because it’s impossible for me not to think about Najaf when I contemplate the situation in Syria. The battle of Najaf happened, basically, because the US Marines and Moktada Al Sadr’s Mahdi Army got trapped into an escalating “tit for tat” until the marines decided a show of imperial force was necessary and went door-to-door through Najaf. As we can see, that successfully suppressed the insurgency in Iraq. [wikipedia] I’m being sarcastic, of course: the Mahdi Army negotiated to leave Najaf if it disarmed, which it did – and now how many of today’s ISIS fighters do you think stood against the Marines in Najaf? Do people in Washington simply imagine that Al Sadr’s militia got jobs in the “gig economy” driving for Uber?

That bit in The Best and The Brightest has stuck with me for decades; it’s a perfect description of how civilian politicians don’t treat the military as a political entity – they fall for the whole “we follow orders” thing. In Obama’s Wars Bob Woodward describes how the military played Barack Obama on “The Surge” – Obama asked for the Pentagon to give plans for a withdrawal from Afghanistan, and they returned with a plan to commit another 125,000 troops. Obama sent the plan back covered in red ink and the Pentagon replied with a plan to commit another 50,000 troops. When Obama asked for another plan, the Pentagon replied with a plan to commit another 10,000 troops “… and we’ll blame you when it doesn’t work.” I’m not a big fan of Bob Woodward (he trades too much for access, which is ironic, given his history)

The civilian US government has lost control of its military. The Department of Defense (i.e.: Offense) is making its own decisions, and is doing its own thing; there is no grand strategy motivating the use of the US military. This makes them particularly dangerous, since now they feel empowered to provoke situations of their choosing. Does anyone reading this really believe that the President had anything to do with the brilliant idea of scheduling simulated decapitation attacks against the North Korean regime?

One reason you may be hearing less about this from the media is that Trump administration stops disclosing troop deployments in Iraq, Syria, “a departure from the practice of the Obama administration, which announced nearly all conventional force deployments.”

This reminds me of Robert McNamara in Vietnam, poring over night patrol reports, and after giving his analysis, being politely taken aside and told that the night patrol data had been completely made up. The US military had given up night patrols long before McNamara’s visit, as they had simply been suicide missions.

—————-

The US media is terrible on Syria, and the rest of the Anglosphere isn’t much better. You could ring random people from a phone book and get better insights I reckon.

I doubt that many of the people who fought against the US in Najaf are with ISIS these days, since Sadr’s followers were mainly Shiites, while ISIS are Sunni fundamentalists who persecute Shiites. More likely those who are still fighting are part of one of the Shiite militias fighting ISIS alongside the Iraqi army, or part of the regular Iraqi army.

Overall, though, I agree with what you are saying here. The problem is that ISIS operates as both a conventional and a guerilla force, so now that it is being defeated in more conventional combat it can simply go back to relying on guerilla activity in any place where it can get significant support (which includes many countries).

It’s been a long time since I read The Best and the Brightest, but I am by coincidence just finishing The Coldest Winter, about the US involvement in the Korean War. It was Halberstam’s last book before he was killed in a car accident about 10 years ago, and I found it quite good.

Does anyone reading this really believe that the President had anything to do with the brilliant idea of scheduling simulated decapitation attacks against the North Korean regime?

It does seem a lot like President Bannon’s thinking, actually.

I had a question similar to spring73, I thought the Madhi army was Shia and ISIS Sunni.